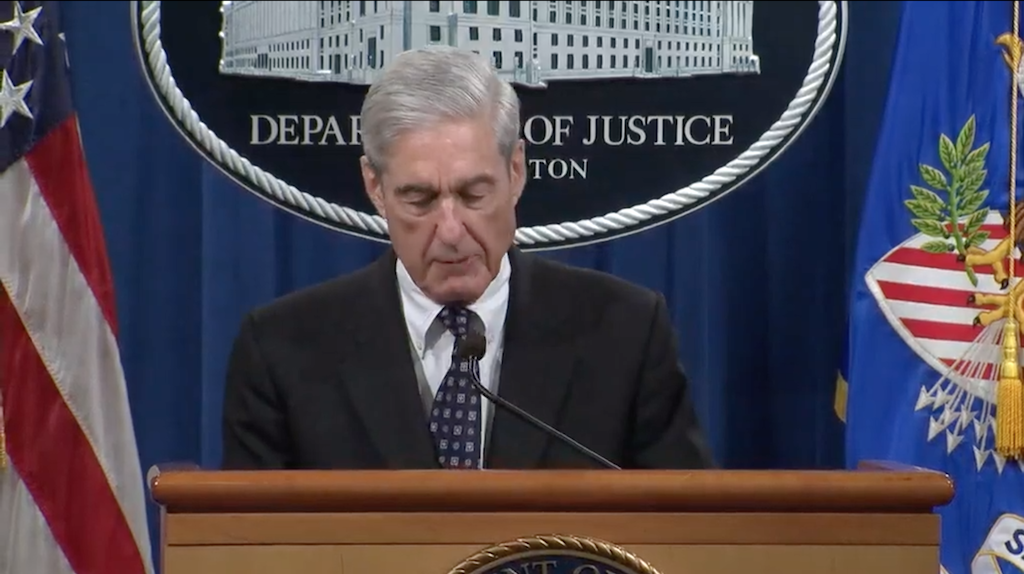

Reflections on Robert Mueller

Robert Mueller must have known that he was having serious trouble with his public when New York Times columnist Gail Collins suggested he might be a wimp.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Robert Mueller must have known that he was having serious trouble with his public when New York Times columnist Gail Collins suggested he might be a wimp. When Mueller was appointed special counsel, Collins was satisfied that he was “a very serious choice” for the role; last week she mused that while “a lot of us thought he’d wind up as a chapter in the history books of the future,” he may qualify now for no more than “an asterisk.” Others commented more in sorrow than in anger. In a Times op-ed, Robert De Niro even stepped outside his “Saturday Night Live” portrayal of Mueller to implore him to speak out more forcefully. Overall, there was evidence of smashed hope, as in this headline: “Disappointed Fans of Mueller Rethink the Pedestal They Built for Him.”

Now Democrats, progressives and others horrified by Donald Trump have come to at least this agreement with the president: There are problems with the way Mueller did his job. Republicans were first, and quick, to sour on the special counsel. The president they chose to follow pounded away at the illegitimacy of the investigation, alleged partisan bias in its conduct, and concocted zany theories of personal conflicts of interest that disqualified Mueller from holding the position. For entirely different reasons, and expressed far less virulently, the other side of the aisle has begun to join the crowd of Mueller critics.

It has been a steep fall for Mueller, the straight-arrow law enforcement professional known and much admired for going “by the book.” His background, history of service and reputation had made his appointment especially compelling. In 2011, when Congress extended his FBI director term by two years, the Senate vote was unanimous. Congressional leaders made clear that it had not lightly made the exception to the 10-year limit for the position; but Mueller—then described in news reports as “widely respected by lawmakers on both sides of the aisle”—was deemed a good reason to do it.

Then, when Mueller was appointed as special counsel, USA Today advised its readers that “a Congress utterly fractured by partisan bickering came to rare bipartisan agreement … as members of both parties effusively praised the selection of former FBI director Robert Mueller.” Jason Chaffetz, a reliable Republican congressional warrior, pronounced it a “great selection,” one that should be “widely accepted.” Even Freedom Caucus Chair Mark Meadows, noting that Mueller credibility might be greater with Democrats than Republicans, offered that “he has credibility on both sides.”

In these polarized times, many imagined that, drawing on his well-earned reputation, Mueller could take on this extraordinary assignment in a deeply divided political environment and pull it off. He would, because he was Bob Mueller, get the benefit of the doubt on the hard calls.

But playing by the book did not at all times appear adequate to the task. To be the straight arrow was both a blessing and a curse, the reason for the disappointment as well as the original, warm welcome. In the Russia investigation, Mueller was under pressure to enforce not just the law but also norms of appropriate presidential conduct; to stand up for the rules but, if necessary, break new legal ground; to vindicate regular order when the president and key associates at the center of his inquiry hold regular order in contempt.

Many of those who cheered his arrival and supported him in his mission had little use for a “by the book” conservative approach, believing that he was operating under emergency conditions. This was a case, after all, about a president charged with colluding with a foreign power to win an election; a president who felt free to throw up one obstacle after another to accountability. Commentators calling for aggressive prosecution counseled Mueller to find ways around the limitations imposed by the special counsel rules. He was urged to steer around the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) opinion prohibiting the indictment of a sitting president. He was exhorted to find ways to inform congressional impeachment deliberations, via a “road map” or otherwise, when, under the special counsel rules, he lacked the authorization formerly given to independent counsels to identify potentially impeachable offenses and was limited to communicating on confidential terms with the attorney general.

In many respects, Mueller held his familiar ground, going by the book. Unlike Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr, he stayed out of the press, eschewing leaks and tit-for-tat exchanges through spokespersons with the ceaselessly bellicose Trump and his lawyers. He was conservative in much of his reading of the law—such as, at least in my view, the punches he pulled in the campaign finance analysis of the Trump campaign’s engagement with the Russian government. He not only accepted that he was bound by the OLC opinions immunizing the president from prosecution, but he also read them, surprisingly (again, in my view, mistakenly), as preventing him from expressing even a conclusion about the legality of the president’s obstructive conduct. He took a sort of institutional high road, arguing that an unindictable president should not be confronted with a legal finding he could not challenge in a formal legal proceeding. He did not force the issue of the sit-down interview Trump rejected, apparently weighing its possibly limited value against the extended delay and uncertainties, and possibly even further disruption to government, entailed by protracted litigation.

Yet Mueller also improvised, apparently concluding that he had to depart in some respects from the most conservative editions of the “book.” The report he wrote was not a simple statement of the reasons his office pursued or declined prosecutions, which seems more like what the special counsel rules contemplated. He turned out an opus, packed with detail, which he surely understood—and, by his own account, hoped—would see the light of day, as it did. While he declined to make a “traditional prosecutorial judgment” about obstruction, he staked out aggressive, controversial ground on the theory of presidential liability for this offense and then indulged in un-Mueller-like commentary in explicitly refusing to “exonerate” Trump. He wrote a letter to the attorney general to protect his four-page summary of the report knowing that this, too, would become public, even though the rules commit all questions of publication or public commentary to the attorney general.

In the end, Mueller was hardly as free-wheeling as a Comey, but he was not the purest version of the straight arrow. One could imagine a range of choices far more self-limiting, more conservative in approach and theory, than the ones he made. He worked with the materials at hand and within challenging conditions: the OLC opinions, certain of the limitations of the special counsel rules, the outrageous behaviors of a president that tested the boundaries of established law and norms, the unprecedented nature of a number of the legal issues. To navigate this treacherous course, with all the intense expectations, Mueller eventually pushed the boundaries.

It would not be enough for some critics and far too much for others. If too much the straight arrow, he would risk being a chump, failing to rise to the demands of the moment. If not enough the straight arrow, he would put at risk the credibility, accumulated over the course of an exceptionally distinguished career, that prompted his well-received appointment.

Of course, the disposition, or suspended judgments, affecting Trump personally does not tell the whole tale of Mueller’s work. In two years, he secured indictments, convictions or pleas from 34 individuals and three companies. His prosecutions included Trump’s former campaign manager and his national security adviser but also members of Russian military intelligence and individuals with clear ties to the Kremlin. He sent an unambiguous message to Moscow. He did so in less than two years.

But there was little chance that Mueller would end his investigation to the bipartisan acclaim that greeted his appointment. This era is not one with much room for the hero who can overcome the pervasive partisanship; it is one in which the legitimacy of a process is judged primarily by its outcome. American political culture is not especially kind to the straight arrow right now. In principle, a special or independent counsel is an outstanding lawyer with a record of impartiality and fairness who has earned the public’s confidence and will keep it. In the politics of the day, a law enforcement professional like Mueller who might have been celebrated as having “near mythic” status will not enjoy it for long.

Did Mueller make mistakes? Democrats and Republicans are increasingly united in the belief that he did. First-rate scholars have argued a range of failures, including Richard Pildes’s contention that Mueller abdicated a “core responsibility” in declining to reach a judgment on obstruction of justice and Jack Goldsmith’s argument that the Mueller report misapplied the law governing a president’s exposure to liability for obstruction..

Perhaps it is inevitable that by one standard or another, given the choices he faced, Mueller would make mistakes or misjudgments, or leave himself exposed to the charge. The most that can be hoped of someone in Mueller’s position is that if he makes mistakes, it will be apparent that he erred in good faith, not for condemnable lack of judgment, independence or courage—and that had another been appointed instead, that special counsel would have done no better and, in all likelihood, far worse.

And now, at the end, we have the squall over his wish to have his report speak for him without further comment or congressional testimony. In this sense, he is one more time going by the book—the one he wrote, online and in bookstores around the country, still number one on the New York Times bestseller list.

.jpg?sfvrsn=676ddf0d_7)