The Refugee Act of 1980: A Forlorn Anniversary

Despite the pall that hangs over the anniversary, an examination of the Refugee Act’s architecture may foster appreciation of what it achieved and provide guidance for overcoming today’s global refugee and asylum dysfunction.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

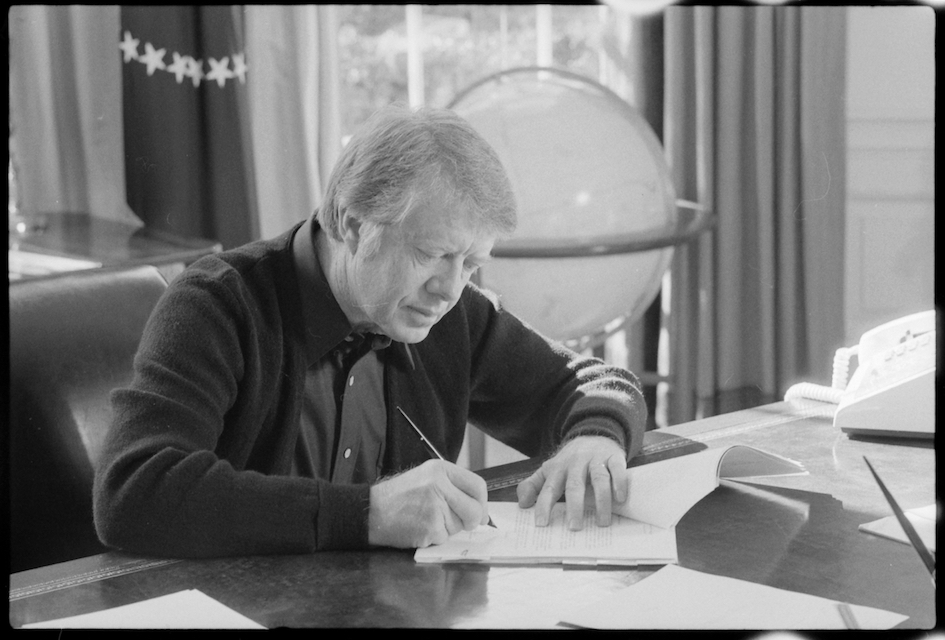

Forty years ago this week, President Jimmy Carter signed into law the Refugee Act of 1980. The statute became the basis for successful resettlement of more than 3 million refugees from distant countries to the United States—a significant humanitarian achievement, and one from which our economy, culture and even cuisine have benefited. Resettlement has also helped resolve or ameliorate foreign policy crises. And the act reshaped and clarified the U.S. framework for political asylum.

We should be celebrating these accomplishments. Instead a pall hangs over this anniversary. The current administration’s hostility to refugee admissions provides the primary reason. But the past five years or so have also starkly revealed the deep practical tensions built into the international asylum system. The U.S. and Europe have struggled to cope, and politically durable asylum solutions are elusive.

A closer examination of the act’s architecture, regarding both quota resettlement and political asylum, may foster appreciation of what it achieved and perhaps provide guidance and inspiration for overcoming today’s dysfunction.

Refugee Resettlement

Before the Refugee Act, federal law expressly provided only 17,400 “conditional entries” each year for refugees screened and selected overseas. Only persons fleeing communist countries or the Middle East were eligible.

Of course, resettlement needs would sometimes, even often, exceed statutory bounds. When this happened, presidents since the failed Hungarian uprising of 1956 have resorted to use of the immigration parole power. But parole was a poor fit. The parole statute technically allowed only temporary permission to stay in the United States, and it opened no path to permanent residence or citizenship—even though everyone expected these refugees to make their permanent home here. Many members of Congress considered refugee paroles illegitimate. They responded by dragging their feet when asked to fund resettlement, hampering efforts to induce allies to assist. Forward planning suffered.

By 1979, as the boat outflow of refugees from Vietnam reached desperate levels (there were 54,000 arrivals in nearby countries in the month of June alone), it became clear that a new system was needed. Carter administration experts and members of Congress then negotiated to produce draft legislation—this was an era when bipartisan commitment to refugee assistance was commonplace. The drafters aimed for greater flexibility and wider scope to deal with refugee crises than the “conditional entry” provision allowed, but they wanted a disciplined process that would facilitate planning, budgeting and realism.

To meet these objectives, lawmakers crafted an innovative framework empowering the president to set refugee admission totals and allocations among refugee groups, through a formal proclamation at the start of each fiscal year. In this framework, there is no requirement for congressional approval; such a procedure would inevitably hamstring response. But transparency and regular accountability are served through mandatory Cabinet-level consultations with the key congressional committees, based on a lengthy annual report on specified elements such as conditions in source countries, resettlement responses by other nations, resettlement costs and economic impacts. The act also standardized assistance to refugees and to the communities and assistance organizations that receive them.

U.S. refugee admissions during the first year of the act’s existence—at the height of the Vietnamese exodus—exceeded 200,000; declined to 159,000 the following year; and then varied between 40,000 and 130,000 over the next 35 years, except for two lean years after the September 11 attacks. Shortly before the 2016 election, President Obama responded to then-record levels of global displacement by using his Refugee Act authority to set the admission ceiling at 110,000 for fiscal 2017, a high level not seen since 1995.

That humanitarian responsiveness didn’t last long. One week after his inauguration, President Trump invoked emergency powers to reduce refugee admissions to 50,000, while decreeing a ban on all Syrian refugees. Shrinkage continued over the next two years, until Trump set the ceiling for 2020 at 18,000—mockingly close to the statutory ceiling of 17,400 that Congress had repealed in 1980. That proclamation came at a time when the U.N. refugee agency was reporting the highest levels of displacement on record, 70.8 million people.

This dispiriting situation is not the fault of the Refugee Act, and it can be fixed without new statutes. The annual consultation structure remains sound. It needs only a president who honors America’s humanitarian heritage, instead of tacitly mocking it. Quota admissions could remain carefully controlled and selective, but on a scale more suitable for today’s global displacement.

Political Asylum

Asylum poses more difficult challenges, because asylum seekers show up on their own initiative. Asylum protection is available in principle to anyone who demonstrates the requisite risk of persecution in the home country. Therefore the asylum remedy does not lend itself to prior screening and selection of applicants, nor to deliberate annual quotas—features that keep overseas resettlement under visible control and minimize public backlash.

The Refugee Act nonetheless made important progress at the time of its passage. It specifically mandated the creation of an asylum application process for persons in the United States or at the border, and it tied U.S. protection to U.N. treaty standards. It also created a new immigration status, now called “asylee,” for those who meet the refugee standards. For the first time, asylees were guaranteed family reunification rights, and the act provided asylees a path to a full green card after one year’s presence.

What the act didn’t do, and what no wealthy country has done with sustained success, is to hold the asylum system steadily within political tolerances, When asylum seekers come in moderate numbers, publics in Europe and America have shown themselves supportive. When numbers climb and government control seems ineffective, support erodes.

Europe experienced such a backlash in 2015-2016, after Chancellor Angela Merkel’s bold offer of haven for Syrian refugees taking rafts to Greece resulted in a million new arrivals in Germany alone. The hoped-for support from other EU countries never materialized. To the contrary, several EU countries strung razor wire to prevent asylum seekers from entering, and extremist anti-immigrant parties found unprecedented success at the ballot box.

Political alarm in the United States over escalating asylum claims struck in 2014 after a decade and a half of relatively low flows and low controversy. That year brought the arrival of 69,000 unaccompanied children from Central America at the southwestern border, plus another 68,000 persons arriving in family units with children. The Obama administration took strong steps that reduced the number of applicants for a few years, but controversy reignited with particular force in 2019. That year saw record numbers (as many as 140,000 a month) arriving from Central America. This overwhelmed government capacity even to house, much less to process and vet, the arriving claimants.

Over the past five years, the world has learned that public alarm about a seeming loss of control over the asylum process implicates greater consequences than just producing bad immigration policy. Portraying immigration as out of control has become perhaps the most potent weapon wielded by authoritarian politicians to win elections and install “illiberal democracy,” as Hungary’s Viktor Orban labels his achievement. Harping on the failures of strained asylum systems, autocratic parties have made significant gains in elections in Italy, Poland, Spain, Austria, Switzerland, Germany and elsewhere. Sadly, the United States also belongs on that list.

In this hazardous political climate, the stakes are high, and it makes sense to experiment with new models for dealing efficiently with asylum claims so as to reassert a degree of control. This is especially true in a regional framework that also tries to alleviate conditions in the source countries. But such experiments have to display the same mix of pragmatism and humanitarian concern that animated the Refugee Act’s creation.

Here too the Trump administration has shown us how not to proceed. It first adopted a host of hasty and ill-considered initiatives to thwart asylum claims, including a presidential proclamation providing that all asylum applicants had to apply at a port of entry. Many of these initiatives were ruled invalid by courts, often because they conflicted with specific language added to the immigration laws by the Refugee Act. The administration is now placing primary reliance on its “remain in Mexico” policy, implemented with the cooperation of the Mexican government. That program is indeed innovative, but it is strikingly deficient in providing safe and sanitary accommodation for the people forced to remain. Many asylum seekers live in flimsy shelters or tent cities along Mexico’s border, where they are easy prey for cartels and petty criminals, while waiting months for the chance to return to the U.S. border for a hearing. Further, the logistics of immigration court appearances for this population are complicated and unreliable, and even minimal consultation with counsel is hard to arrange.

A more promising set of innovations to deal with high numbers of applicants along the southwestern border was proposed last year by a bipartisan panel of the Homeland Security Advisory Council, an official federal advisory committee. It called for processing centers just inside our southwestern border, where applicants would be obliged to remain pending adjudication. This means detention during the process, but it would be under housing and custody standards far safer than the Mexico situation, and families would remain together. All the players involved in asylum adjudication (such as judges, government attorneys and interpreters) would be co-located to permit rapid adjudication of claims. And the panel recommended vigorous diplomacy and aid projects to enhance safety in the source countries—something the Mexican government has also favored.

Of great significance, the panel also recommended serious consideration of government-funded immigration counsel for the applicants, modeled on a public defender’s office. This bold step would help ensure rapid processing, while improving fairness, and it may make reviewing courts far more ready to respect the resulting rulings.

The Department of Homeland Security has shown no sign of acting on these parts of the panel’s proposal. Its leadership is firmly committed to the “remain in Mexico” policy despite initial court rulings finding that policy inconsistent with the applicable statutes. The Supreme Court has stayed the application of those court orders pending completion of all appeals, which will not happen before the November election.

When the Refugee Act was adopted, the world’s population stood at 4.5 billion. The act was designed to implement a 1951 U.N. refugee treaty, drafted when the globe held 2.5 billion people. In 2020, with world population at 7.5 billion and cheap transportation and communication widely available, classic asylum systems inevitably face enormous political strains. We must expand our horizons in seeking novel ways to balance protection and control. As we confront that titanically challenging task, we need to apply the mix of humanitarian dedication, realism and creativity manifested in the Refugee Act.

.jpg?sfvrsn=676ddf0d_7)