Remembering the Bombardment of Greytown

On this date in 1854, the U.S. Navy bombarded and torched the town of Greytown, in present-day Nicaragua. The event gave rise to a federal court opinion by Justice Samuel Nelson favored by modern-day lawyers who believe that the president wields vast unilateral power to use military force. The story behind the case reveals much more about how presidential naval powers, as well as congressional checks, operated in the mid-19th century.

Durand v. Hollins

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On this date in 1854, the U.S. Navy bombarded and torched the town of Greytown, in present-day Nicaragua. The event gave rise to a federal court opinion by Justice Samuel Nelson favored by modern-day lawyers who believe that the president wields vast unilateral power to use military force. The story behind the case reveals much more about how presidential naval powers, as well as congressional checks, operated in the mid-19th century.

Durand v. Hollins

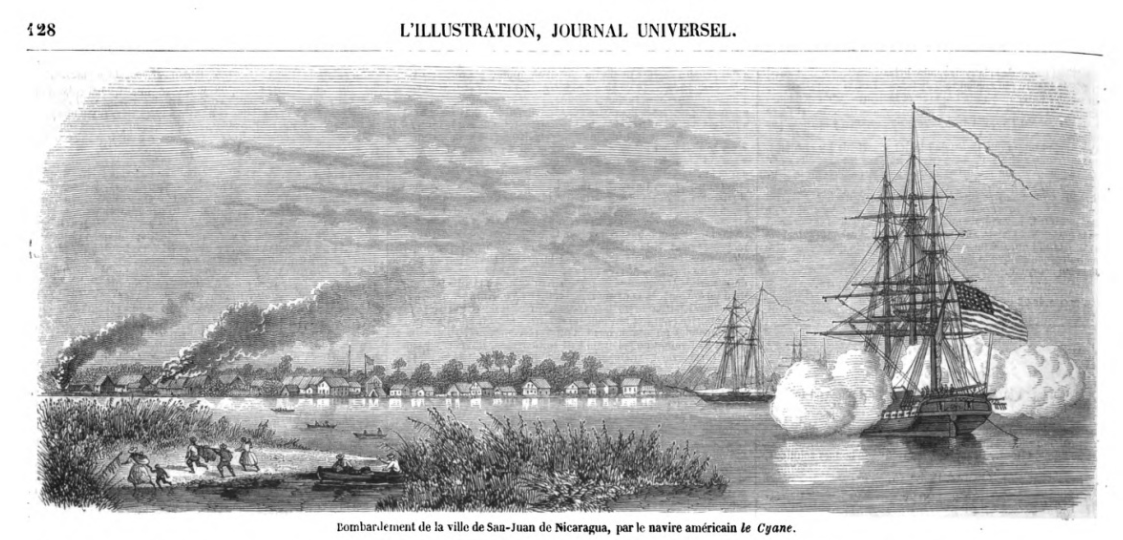

The judicial case, Durand v. Hollins, 8 F. Case. 111 (C.C.D.N.Y. 1860), seems rather straightforward, though the holding can be read very broadly. The plaintiff, a New York merchant named Calvin Durand, sued U.S. Navy Commander George Hollins, who captained the American sloop-of-war Cyane, over the destruction of Durand’s property. Hollins had ordered his vessel and crew to bombard and burn Greytown, also known locally as San Juan del Norte, on Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast. Hollins responded that he had acted pursuant to binding orders from the president and the Navy secretary, who had directed him to use force in redressing local seizures of American property.

Nelson, sitting as circuit justice, ruled in favor of Hollins. In so doing, he declared the president’s constitutional powers to protect American lives and property abroad to be very capacious:

Now, as it respects the interposition of the executive abroad, for the protection of the lives or property of the citizen, the duty must, of necessity, rest in the discretion of the president. Acts of lawless violence, or of threatened violence to the citizen or his property, cannot be anticipated and provided for; and the protection, to be effectual or of any avail, may, not unfrequently, require the most prompt and decided action. …

The question whether it was the duty of the president to interpose for the protection of the citizens at Greytown against an irresponsible and marauding community that had established itself there, was a public political question, in which the government, as well as the citizens whose interests were involved, was concerned, and which belonged to the executive to determine; and his decision is final and conclusive, and justified the defendant in the execution of his orders given through the secretary of the navy.

With such sweeping language, and because courts rarely reach the merits of war powers disputes, it is no surprise that the Justice Department and scholars frequently cite this lower court case to support expansive presidential powers. See, for example, here for its use by then-Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) chief William Rehnquist in justifying incursions of Cambodia during the Vietnam War, and here for the OLC’s 2014 use of the case in justifying strikes against the Islamic State. If the United States launches limited strikes against Iran, I will not be surprised if the Justice Department cites this case in its justification. Nelson’s holding is especially interesting because less than a decade later he dissents in the Prize Cases, contending that Lincoln lacked constitutional authority to blockade Confederate ports before Congress declared war.

I have long wondered about the story behind Durand v. Hollins. How, after all, did these actions by the Franklin Pierce administration come to occupy a special place in presidential war powers jurisprudence? As American overseas commercial interests expanded between the War of 1812 and the Civil War, presidents directed many other demonstrative threats or uses of naval force, some of them even more destructive, that few lawyers would ever pay much attention to because they did not involve litigation over Americans’ property. The Greytown bombardment was not even the most significant show of naval force in the summer of 1854; at around that same time, Commodore Matthew Perry and his squadron were brandishing armed strength in Tokyo Bay to open Japan to American diplomacy.

It turns out that the Greytown story is much more interesting than I expected, as well as revealing about how constitutional military powers operated in that era.

Greytown in Context

Greytown was an especially important spot for American commerce in the 1850s because of the California gold rush. The easiest route from the eastern United States to California at that time was first by sea to Greytown, situated at the mouth of the San Juan River. Gold rushers would from there travel by river, land, and two lakes to the Pacific Ocean, and then onward to San Francisco. Demand for this travel was so high that Cornelius Vanderbilt obtained a monopoly concession from Nicaragua and established the Accessory Transit Company to service it. Although Vanderbilt had lost control of the company by 1854, the Greytown mobs threatened American property in a place made famous by one of the country’s richest men.

Greytown was also an important spot for American competition with Britain, and although the bombardment did not escalate, it could have had major diplomatic consequences. Britain—whose navy was still about 10 times larger than the United States’s—was seeking to maintain its power over parts of Central America, and Greytown was, at that time, located within a British protectorate. Both the United States and Britain eyed Greytown as a possible site for an isthmian canal, if that project were eventually undertaken. Because bilateral relations were improving at the time, and Britain was occupied by the Crimean War, Britain was willing to let this incident go.

These specific circumstances illustrate some general points about American foreign policy in the decades before the Civil War. On the one hand, the United States used naval power—that is, shows of force and sometimes violent demonstrations of it—to protect its rapidly expanding commercial interests abroad. On the other hand, it sought to avoid direct confrontation with major European powers.

Instructions to naval commanders, usually issued by the secretary of the Navy, were a critical policy instrument for mediating these imperatives. More rapid transportation and communication technologies—especially railroads, telegraphs and steamships—were coming online during the antebellum period. But it could still take weeks, or even months, for information to travel between Washington and naval units patrolling distant seas. At this time, a steamship would take about a week to travel from Washington to Greytown; it would have taken the Cyane longer to sail.

If timely and decisive military action were deemed sometimes necessary, it would have been impractical to coordinate naval actions closely with the administration in Washington, let alone to seek advance congressional authorization for each use of force. Instead, to account for the limits of communication across vast distances, executive branch naval orders were usually drafted to give commanders substantial discretion in operating militarily and diplomatically, within broad parameters. As explained below, naval instructions are important to the Greytown story.

This discretion conferred in naval orders, of course, created dangers that commanders would sometimes overstep. The most startling example occurred in 1842, a time of heightened tensions with Britain and Mexico, when a Navy commodore was directed to patrol the Pacific coast of North America and protect American interests. In October of that year, his squadron landed near Monterey, then still part of Mexico and, mistakenly believing that the United States and Mexico were at war, he seized a fort. The next day, the commodore realized his mistake, re-raised the Mexican flag and retreated. The Tyler administration in Washington did not learn of the event until January 1843—three months later—provoking a congressional inquiry and requiring an apology to Mexico.

Geography and 19th-century technology thus contributed to assertions of presidential power in several ways. Slow communication across vast distances demanded executive agility in wielding force abroad. At the same time, oceanic barriers afforded the United States relative security against European powers that mitigated the dangers of overzealous commanders. Those oceanic barriers also allowed the United States to adopt muscular practices for defending its expanding commercial interests without needing large peacetime military establishments that would elicit domestic backlash.

Returning to the Greytown story, in May 1854, events got out of hand. The captain of an American commercial vessel shot and killed a local man. When a crowd of residents tried to arrest the captain, the U.S. minister to Nicaragua held them off at gunpoint. Locals then tried to apprehend the minister, who was hit in the face by a thrown bottle, whereupon he returned to the United States and urged a strong American response.

The agent for that response was Commander Hollins. On June 10, 1854, Navy Secretary James Dobbin issued new instructions “in pursuance of the wishes of the President” to Hollins. Advising Hollins that “[t]he property of the American citizens interested in the Accessory Transit Company, it is said, has been unlawfully detained by persons residing in Greytown” and “[a]pprehension is felt that further outrages will be committed,” Dobbins directed Hollins to further assess the situation and issued the following instructions:

Now, it is very desirable that these people should be taught that the United States will not tolerate these outrages and that they have the power and the determination to check them. It is, however, very much to be hoped that you can effect the purposes of your visit without a resort to violence and the destruction of property and loss of life.

Arriving at Greytown’s harbor on July 11, Hollins warned local authorities that they had 24 hours to provide adequate apology and compensation for the damage to Transit Company property and insults to the American minister. When that notice went unheeded, on July 13 Hollins opened fire on the town. He then sent a landing party of Marines to set fire to it. Hollins gave residents opportunities to flee, so no one was killed, but the town was reduced to ashes.

Congressional Checks on Antebellum Naval Force

Although the federal court in Durand v. Hollins six years later upheld the assault as within the president’s authority, the events more immediately sparked constitutional controversy in Congress and the press. Such controversy was not uncommon after U.S. naval forces took strong military action, usually against what today we would call nonstate actors and were then—and in this case—referred to as pirates, brigands or savages. Occasionally, presidents would disavow military operations as beyond their instructions, and there is strong evidence suggesting that Pierce considered doing so in this case.

Pierce ultimately defended the actions about six months after the military strike, dedicating a substantial part of his December 1854 annual message to Congress to an explanation of Hollins’s instructions and their application to the facts. His justification emphasized, in addition to the threats to U.S. interests, Greytown’s lack of “regular government” authority. Noting that his instructions emphasized avoiding military force if possible, Pierce claimed that force was, indeed, necessary against the offenders to avoid “leav[ing] them impressed with the idea that they might persevere with impunity in a career of insolence and plunder.”

In the aftermath of Greytown, Congress exercised a specific form of oversight: Both houses passed resolutions requiring the president to turn over the relevant instructions issued to naval commanders. Such demands were a familiar investigatory tool that Congress used in other, similar incidents of naval force during the period. The Pierce administration turned over the Hollins instructions as well as extensive communications between Hollins and other officials in the bombardment’s lead-up and aftermath.

This was not toothless oversight, because Congress’s power of the purse was especially potent in an era of expensive and politically controversial naval expansion. Naval actions like Hollins’s fed fears in some quarters that peacetime naval forces were prone to militarism. Presidents, such as Pierce, who wanted to expand and modernize the U.S. Navy thus had to repeatedly persuade Congress that these forces were necessary as well as controllable.

In this case, a small but vocal set of House members accused the president of infringing on Congress’s power over war. A week after Pierce’s defense of the Greytown bombardment in his annual address, Rep. John Wheeler from New York unsuccessfully called for a special committee to investigate the incident and whether it violated the Constitution. Wheeler was Pierce’s fellow Democrat, but he also represented merchants, including Durand, whose property had been destroyed. In a January 1855 floor speech, Rep. Leander Cox, an opposition Whig Party member, noted that the constitutional framers gave Congress exclusive power to declare war. Moreover, he continued pointedly, “War can be begun without any declaration, and when the sword is drawn, and bathed in the blood of an adversary, the nation is at war and must be responsible for the consequences. Where, then, was the power found to demolish Greytown?” The next month, Rep. Rufus Peckham, another of Pierce’s fellow Democrats from upstate New York, attacked the bombardment of Greytown on many grounds, including that it was unconstitutional war-making by the executive branch. Peckham made these statements during a committee debate on naval appropriations, and he attempted to deny funds requested by the Pierce administration for the construction of steamships. In the end, neither Congress as a whole nor the House took any formal action against Pierce or his naval agenda following its review of the matter.

A Coda on Congressional Force Authorizations

If case-by-case congressional authorization of force was impractical in cases like Greytown, one might wonder whether a better way to regulate naval power in this era would have been through broad congressional force authorizations for certain general types of threats, perhaps in particular regions. It so happens that Pierce’s successor, James Buchanan, unsuccessfully tried that in a way that resonates in present-day debates about the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) or Congress’s authorization of some offensive cyber operations.

Buchanan took a very narrow view of the president’s unilateral war powers (incidentally, he served as Pierce’s minister to Britain, so it had been his job to soothe bilateral friction arising from the Greytown incident). Agreeing with some of Pierce’s congressional critics that only Congress could initiate hostile military action, Buchanan took a different approach to coercive naval power: On several occasions in the late 1850s, he sought legislative authorizations of force in advance to protect from violence American interests in Latin America.

For a variety of reasons, especially partisan and strategic ones, Congress declined. There was, though, also constitutional pushback against the idea of general force authorizations and questions as to whether Congress could delegate authority to use force in advance of specific provocations. For example, when Buchanan asked Congress in 1859 to approve necessary force to protect American interests in the Central American isthmus, New York Sen. (and Lincoln’s future secretary of state) William Seward objected:

Could anything be more strange and preposterous than the idea of the president of the United States making hypothetical wars, conditional wars, without any designation of the nation against which war is to be declared: where the time, or place, or manner, or circumstance of the duration of it, the beginning or the end: and without limiting the number of nations with which war may be waged? No, sir.

Within two years, this war powers issue would seem trifling. These days, some members of Congress raise similar objections to proposals that they call open-ended authorization against terrorist threats.