Remembering the Selective Draft Law Cases

On this day in 1918, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the constitutionality of a national draft. That ruling illustrates how military powers in the Constitution have continuously adapted throughout American history to changes in warfare.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

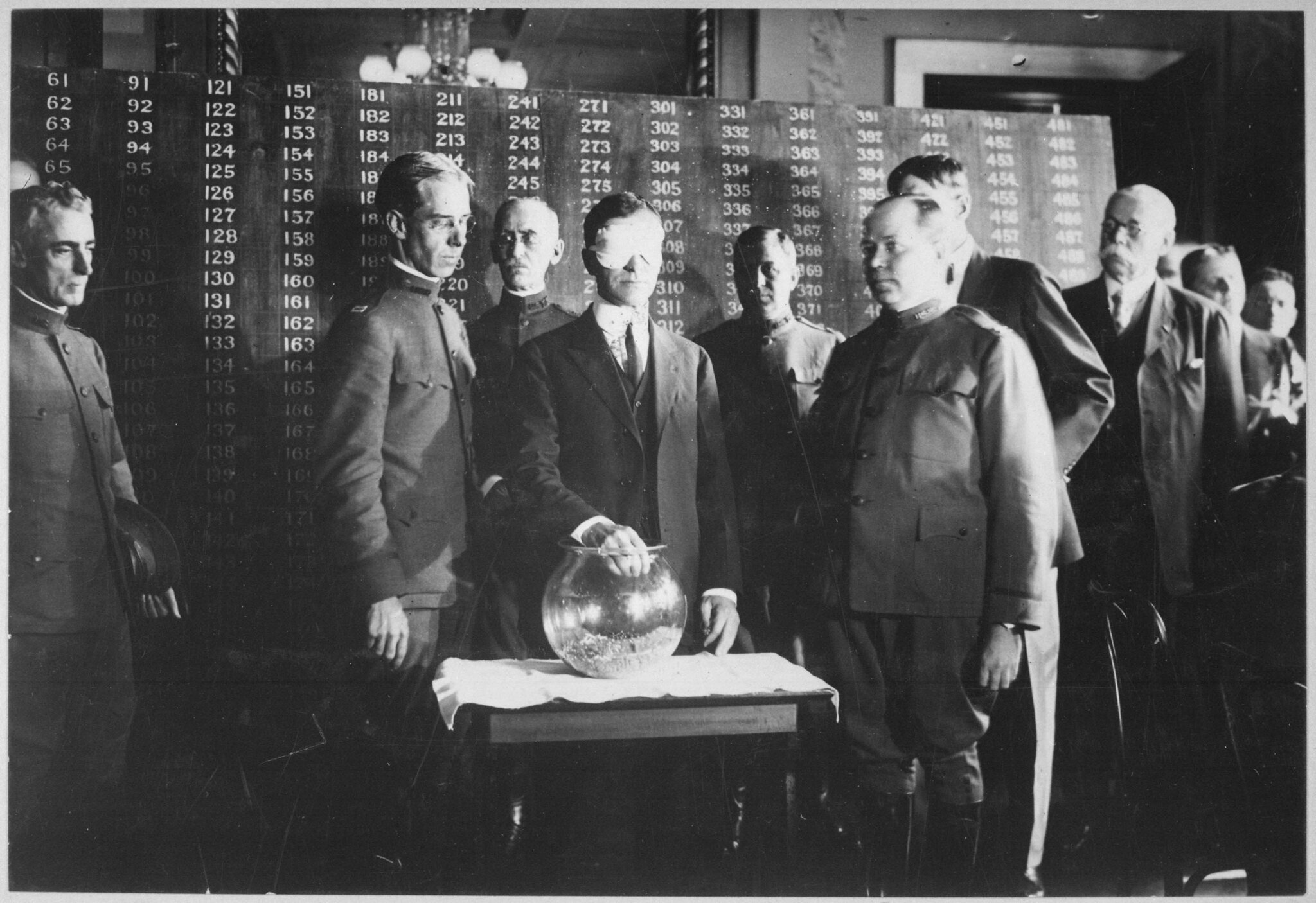

On this day in 1918, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the constitutionality of a national draft. The combined cases—referred to collectively as Arver v. United States or the Selective Draft Law Cases—involved a set of constitutional challenges by individuals who were prosecuted for violating the federal Selective Draft Law of May 18, 1917. Congress enacted that law shortly after it declared war in April 1917. Among other things, the act required, upon presidential proclamation, all male citizens aged 21 to 30 to register for the draft and delegated to the executive branch authority to determine which ones would be called into compulsory military service.

In a rambling, barely-coherent opinion for the Supreme Court, Chief Justice Edward White wrote that Congress had the power to enact that national draft by virtue of its combined Article I power to “raise and support armies,” its other war and military powers and the Necessary and Proper Clause of the Constitution. That decision is likely to feature in a Supreme Court case this term, Torres v. Texas Department of Public Safety, which considers whether Congress may authorize suits against nonconsenting states pursuant to its constitutional war powers. The 1918 ruling also illustrates how military powers in the Constitution have continuously adapted throughout American history to changes in warfare.

Prior Constitutional History of a National Draft

Constitutional controversy surrounding a national draft had a long history. However, not until the Selective Draft Law Cases had the issue come before the Supreme Court.

The first storm around a national draft arose in the War of 1812. As the U.S. military ran short on manpower two years into the war, Secretary of War James Monroe recommended a national draft. Congress narrowly rejected the idea, but the proposal aroused vehement constitutional objections that went unresolved. Leading Federalist Senator (and future Secretary of State) Daniel Webster reflected the predominant New England sentiment when he condemned the proposed national draft, calling the issue “nothing less than whether the most essential rights of personal liberty shall be surrendered, and despotism embraced in its worst form.”

Importantly, most state militias at that time involved some compulsory service, but tradition (and probably the Constitution) limited the purposes to which they could be put. Militias—part-time citizen-soldiers who owed mandatory service for local defense—had a deep history in the American colonies that was rooted in British custom. According to ancient British tradition, militias could only be compelled to serve locally and could not be sent abroad. As part of a constitutional compromise, the terms of the Militia Clause in Article I may be read to limit Congress’s power to call forth state militias to three specified purposes, all of which involve local, not foreign, service: “execut[ing] the laws of the union, suppress[ing] insurrections and repel[ling] invasions.” Indeed, only six years before the Selective Draft Law Cases, an Attorney General Opinion held for these reasons that the president could not call up state militia forces and send them along with regular Army units into foreign countries.

Besides individual rights, early constitutional criticism of a national draft reflected sensitive balances between the federal and state governments. Direct national conscription might be more militarily efficient, but it threatened to sideline militias. Keep in mind that a national Army and Navy are only optional under the Constitution, whereas militias are guaranteed by it. Constitutional objections helped to spike Monroe’s national draft proposal in Congress in favor of reliance on militias and programs to boost voluntary federal enlistments. Such objections over the military relationship between the national government and states also took on special salience four decades later in the Civil War.

To recruit enough troops, the Union turned in 1863 to a national draft for the first time in the republic’s history. The Supreme Court did not take up the draft question during the Civil War, but some state courts did. In the most significant case, with a twist, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court narrowly declared the national draft unconstitutional before quickly reversing itself after a new justice replaced a member of the majority. Chief Justice Roger Taney also privately took it upon himself to pen a draft opinion, despite no relevant cases being before the court, concluding that a national draft was unconstitutional.

The crux of Taney’s detailed memorandum was a structural argument, that a national draft would destroy constitutionally guaranteed powers embodied in the militia clauses. He explained that the Constitution contemplated only two types of military forces: national military forces (the regular Army and Navy) and state militia forces, which could only be called into national service for specified purposes and in accordance with other restrictions—the limited, local defensive purposes—contained in the Constitution’s militia clauses. Taney argued that Congress’s power to “raise and support armies” should be interpreted as limited to voluntary enlistments, which was how it had always been understood and implemented to that point in history. To allow Congress to legislate compulsory Army service would, in effect, give the national government the power to swallow state militias whole since the national government could draft all able-bodied men into the Army, leaving no one to serve in the state forces.

Drawing on these types of arguments, some critics viewed the World War I compulsory Selective Service system as doubly offensive to the Constitution. It threatened states’ militia powers by drafting men into national military service and, by sending draftees overseas, it also eviscerated constitutional restrictions on the purposes to which those called into mandatory service could customarily be put.

The Selective Draft Law Cases

Chief Justice White had fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War, but his disjointed 1918 opinion for a unanimous court gave little credence to Taney’s objections. In a tortuous passage that comes as close as any to summarizing the holding, he writes:

Thus, sanctioned as is the act before us by the text of the Constitution and by its significance as read in the light of the fundamental principles with which the subject is concerned, by the power recognized and carried into effect in many civilized countries, by the authority and practice of the colonies before the Revolution, of the States under the Confederation, and of the Government since the formation of the Constitution, the want of merit in the contentions that the act in the particulars which we have been previously called upon to consider was beyond the constitutional power of Congress is manifest.

Besides the structural arguments that Taney and Webster had raised, he also blew past other objections including that a national draft violated the 13th Amendment’s prohibition of involuntary servitude. Why does he so breezily dismiss these long-standing objections as “frivolous”?

For one, the Civil War itself had helped recast centralized military powers as a vital check against liberty deprivation by states, rather than the other way around. In the early 20th century, a series of reforms to standardize and improve antiquated militias (by then “National Guards”) also had, in return for significant funding to the states, subordinated those state forces to the regular Army. Moreover, the Selective Draft Law Cases took place amid patriotic fervor and government efforts to suppress or drown out dissent, and those factors must have affected the justices, too. At one point during oral argument, counsel for one of the defendants challenging the draft suggested that the American people had not approved the war for which they were being drafted. The Chief Justice shot back across the bench that such a statement “should not have been said to this court” because “[i]t is a very unpatriotic statement.” Consider also the position of the court in January 1918 when it considered the case: The U. S. military had combat troops actively engaged in Europe and was already preparing to send hundreds of thousands more, many of them draftees. Striking down the draft at that point would have been disastrous.

Stepping back, the most significant reason why the Supreme Court casually dismissed traditional constitutional objections, however, has to do with the radical transformations in war itself. By 1918, the European powers had already been at war for more than three years and, as the Supreme Court would observe, had all resorted to national drafts. In flippantly discarding objections, the Chief Justice notes the “almost universal” compulsory drafts “now in force” among the warring powers. He goes on in a footnote to list many of them. Twentieth-century industrial warfare, waged at a new scale, required mobilizing entire societies with unprecedented degrees of government control.

For the U.S., the manpower challenge upon entering the war was not simply how to rapidly expand a pre-war military force of a few hundred thousand (many of them state national guardsmen posted on the Mexican border) into a multi-million-man Army and send them abroad. Because this war was a contest of mass production, the United States also had to raise that Army while maintaining domestic industry. As historian David Kennedy explains, national conscription would be done through selective service “primarily as a way to keep the right men in the right jobs at home.”

In light of these imperatives, I read Chief Justice White’s Opinion in the Selective Draft Law Cases as essentially saying that Article I’s power to “raise and support armies” combined with the Necessary and Proper Clause gives Congress wide latitude to assemble an Army by means as it sees fit. Inside Chief Justice White’s tangled mess of an opinion is the key point that the constitutional power to create national military forces is “wisely left to depend upon the discretion of Congress as to the arising of the exigencies which would call it in part or in whole into play.”

* * *

Reflecting on the Selective Draft Law Cases a century later, a few general points about constitutional war powers stand out. First, that core idea that the constitutional war powers are elastic, virtuously designed to flex as Congress deems necessary, has generally won out over another view that prizes constitutional rigidity and fixed limits in crisis when political leaders are most prone to abuse power. Daniel Webster took that latter view when he opposed a national draft in 1814: “the People have granted all the means which are ordinary and usual, and which are consistent with the liberties and security of the People themselves and they have granted no others. To talk about the unlimited power of the government over the means to execute its authority is to hold a language which is true only in regard to despotisms.” The Selective Draft Law Cases were just one of many controversies in World War I in which war powers-flexibility bested war powers-rigidity.

Second, that constitutional flexibility has resulted in some radical adaptations that are now so well-established that we barely even notice. In the early 19th century, a national wartime draft might very well have been held unconstitutional, as a step down the path of tyranny and militarism. In the Civil War, the question divided courts without clear resolution. In the early 20th century, all three branches of government regarded a national draft as clearly constitutional in wartime. In the mid-20th century (after 1940) it was accepted as constitutional even in peacetime. By the 21st century, a return to a federal draft would be widely regarded as a strong political check against war, turning some early constitutional objections on their head.

Third, this case is a reminder that although today the biggest constitutional war powers controversies are usually thought to be about the president’s powers, historically many of the most consequential debates have been about Congress’s war powers. Moreover, those controversies have not just been about the allocation of war powers among the branches of the national government but also about the allocation of war powers between the national government and the states.

.jpg?sfvrsn=8588c21_5)

-final.png?sfvrsn=b70826ae_3)