Rethinking “Rules of the Road” to Stabilize U.S.-China Competition

China and the U.S. both have an interest in rules and mechanisms to prevent stumbling into great power war. But will these “rules of the road” will actually achieve that goal?

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

As U.S.-China relations continue to deteriorate, strategists and policymakers are calling for the two countries to establish “guardrails” and “rules of the road” to manage great power competition and reduce the risks of a military clash. It’s time to interrogate some assumptions behind these calls and ask whether and how diplomatic negotiations over rules for risk reduction and deescalation can help stave off armed conflict.

A useful place to start is a recent essay by University of Chicago professor John Mearsheimer and an episode of the Lawfare Podcast in which Mearsheimer sat down for a conversation with Lawfare co-founder Jack Goldsmith. Writing in Foreign Affairs, Mearsheimer excoriates U.S. leaders for their policy of engagement toward China over the past 30 years. The essay is a bit of a “victory lap” insofar as Mearsheimer has been warning for decades that U.S.-China rivalry is a tragic inevitability. Despite his bleak prognosis, however, Mearsheimer proposes steps to mitigate the risk that a U.S.-China cold war turns hot. Aside from military deterrence, he argues, “Washington can also work to establish clear rules of the road for waging this security competition—for example, agreements to avoid incidents at sea or other accidental military clashes. If each side understands what crossing the other side’s redlines would mean, war becomes less likely.”

Is the arch-realist Mearsheimer being sufficiently realistic about the prospects of Washington and Beijing finding common ground on rules to prevent conflict escalation? The question is crucial given the stakes: potential high-tech war between nuclear-armed great powers. Mearsheimer’s rationale for establishing these “rules of the road” is captured strikingly during his conversation with Goldsmith in the Nov. 9 episode of the Lawfare Podcast. Remarkably, Mearsheimer’s realist analysis appears to share some of the core assumptions that so-called liberal internationalists hold regarding the importance of the United States writing rules of the road to advance its interests on the international stage.

The problem is that these assumptions are based on a conception of rational self-interest that Chinese leaders do not necessarily share. On the contrary, Beijing often sees putative rules of “risk reduction” as destabilizing—more likely to invite conflict than to prevent it. Understanding this is crucial if American officials hope to establish durable rules to promote peace and stability with China or to properly calibrate expectations regarding what rules can accomplish.

The Logic of Power and the Power of Rules

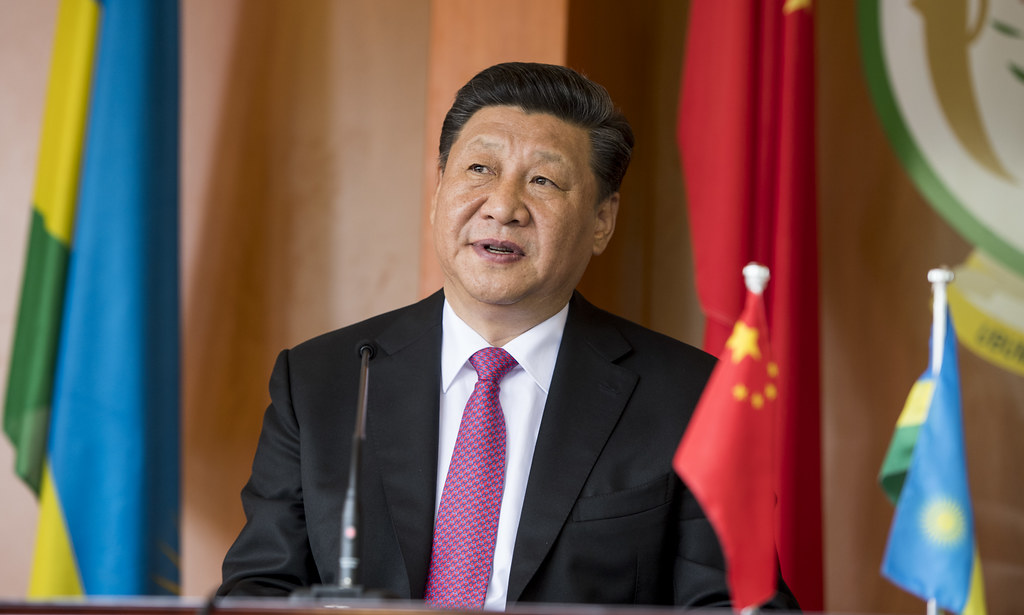

The goal of strengthening U.S-China crisis management and risk reduction mechanisms is a worthy one that I share. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan indicated that this issue was a focal point of discussion in the recent tension-dampening meeting between Presidents Biden and Xi Jinping. (Sullivan and Indo-Pacific Security Coordinator Kurt Campbell argued for such steps in their own 2019 essay.) But what makes the United States think China will commit to and comply with these guardrails?

Mearsheimer’s rationale focuses on trendlines in the balance of power. In his conversation with Goldsmith, he emphasizes the need for the United States to move on this while still in a position of relative power—before it’s too late:

It’s very important to understand that if you assume that China is going to continue to grow over time at a more rapid pace than the United States—which is what most people assume; we don’t know for sure whether this will happen—time is on China’s side. Time works against the United States because China grows more powerful relative to the United States over the next 10, 20 years. This is the argument that China should not cause any trouble over Taiwan now, they should wait 20 years when they’re much more powerful relative to the United States. But what this tells you is that now is the time for the United States to move to establish rules of the road, because our bargaining position, so to speak, only becomes weaker with the passage of time as the balance of power shifts against us.

In linking the urgency of rulemaking with the fact that “time works against the United States,” the realist Mearsheimer finds unusual common ground with no less an icon of liberal internationalism than G. John Ikenberry—Mearsheimer’s intellectual antagonist. Ikenberry deployed similar logic in a 2008 Foreign Affairs essay titled “The Rise of China and the Future of the West,” wherein he advocated a much broader ambition of sustaining an “open and rule-based” international order and incentivizing Chinese integration into that order. Mindful of China’s ascendance and the fact that the United States’ “unipolar moment” would eventually pass, Ikenberry argued that the United States should use its power to entrench the rules of the existing order while it is still in a position of relative strength. Washington must, according to Ikenberry, “put in place institutions and fortify rules that will safeguard its interests regardless of where exactly in the hierarchy it is or how exactly power is distributed in 10, 50, or 100 years.” More recently, Ikenberry has argued that a return to this internationalist spirit of rulemaking and norm construction is exactly what the age of contagion now calls for.

Despite the divergence in Mearsheimer’s and Ikenberry’s theoretical approaches, Mearsheimer in 2021 seems to wield two assumptions that echo those of Ikenberry in 2008. The first is an assumption that Chinese leaders will view acceptance of and compliance with U.S.-preferred rules as being in their interest. Ikenberry in 2008 argued that China would have more to gain than to lose from integrating into and complying with the rules of the “Western-centered” international system. (He has since reflected that “[t]he bet that China would integrate as a ‘responsible stakeholder’ into a U.S.-led liberal order is widely seen to have failed.”) Mearsheimer in 2021 is arguing that China and the United States both have, as he put it to Goldsmith, a “deep-seated interest” in avoiding major accidents and conflict escalation, and thus an interest in rules and mechanisms to prevent stumbling into great power war.

Second, both arguments proceed from a version of the premise that “time is on China’s side” because China’s power is growing relative to the United States’. For Ikenberry in 2008, that meant it was time to “sink the roots of [the liberal international] order as deeply as possible, giving China greater incentives for integration than for opposition and increasing the chances that the system will survive even after U.S. relative power has declined.” For Mearsheimer today, it means now is the time to put guardrails on strategic competition in a way that maximizes the United States’ interest in preventing an accidental war.

It is not obvious that these two assumptions are mutually compatible, at least when it comes to conflict prevention. If the putative rules are in China’s “deep-seated interest” no less than the United States’, then what is the significance of the current balance of power? Why does it matter that China may be better positioned to “write the rules” in the future if the United States does not use its power to write them now? Wouldn’t China see these rules as being in its interest if the shoe were on the other foot?

On the other hand, what if Chinese leaders do not see these rules as being in their interest? Why would Beijing accede to or comply with existing or putative U.S.-preferred rules instead of waiting for the moment when China is more powerful and positioned to get a better deal? Why would Beijing see a need for rules at all if those rules will simply give the United States more confidence to engage in “close-in reconnaissance” and other activities that China perceives as threatening?

How Do Rules Really Work?

In reality, Beijing has not been eager to advance discussions to establish deescalatory rules of the road that, according to Mearsheimer and others, are fundamentally in China’s interests. There are some important exceptions. These include China’s agreement to the 2014 Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES) and two U.S.-China memoranda of understanding (MOUs) on military activities and air and maritime encounters. American commanders have noted that interactions between U.S. and Chinese naval vessels at sea are, for the most part, “predictable and professional.”

At the same time, however, the U.S.-China crisis management mechanisms that do exist remain considerably less robust than those developed with the Soviet Union during the Cold War. As Rush Doshi has explained:

[T]he [Sino-U.S.] Military Maritime Consultative Agreement (MMCA) and U.S.-China 2014/2015 MOUs on aerial and naval incidents are not as binding, detailed, operational, or effective as the U.S.-Soviet Incidents at Sea Agreement. Moreover, the U.S. and China lack a conscious effort at the command level to reduce the risk of inadvertent war, which was the focus of the landmark U.S.-Soviet Agreement on the Prevention of Dangerous Military Activities. Finally, Washington and Beijing also lack anything resembling the robust U.S.-Soviet bilateral arms control process, and crisis communication mechanisms remain comparatively undeveloped.

Certain protocols simply do not address key actors. For example, CUES and the U.S-China maritime safety MOU do not expressly apply to coast guard vessels or to China’s armed fishing militia, despite the fact that such vessels are deployed in gray-zone operations to assert and defend China’s expansive maritime claims “more regularly and extensively” than is the People’s Liberation Army Navy. Existing defense hotlines are underutilized, and proposed theater-specific channels may be of limited value given the misalignment between the operational command structures of U.S. and Chinese forces. In certain domains, such as cyber, nuclear, land and outer space, there simply are “no in-depth protocols between China and the United States covering conflict escalation within or between these arenas.”

Why does Beijing view rules for risk reduction and crisis communication with suspicion? Chinese officials may see negotiations over these rules as U.S. attempts to contain and constrain China’s freedom of maneuver. More fundamentally, Beijing may see the opacity and ambiguity fostered by the absence of clear rules as a source of crisis stability and deterrence insofar as it elicits caution from an uncertain adversary. This is evidenced by, among other things, China’s history of signaling through dangerous intercepts. Beijing may feel more secure if Washington is unsure what Chinese actors will do in an encounter at sea, in the air, or through a cyber network intrusion. Similar logic may apply to China’s nuclear modernization efforts aimed at achieving “mutual vulnerability” with the United States.

China’s ambivalence toward rules of risk reduction and deescalation also raises the more fundamental question of whether this stance is representative of China’s broader approach to international law and institutions. Beijing has acceded to numerous existing international agreements while often treating those rules instrumentally and capitalizing on their gaps and ambiguities. Theorists are at pains to explain the nature of rules and compliance in the international arena, and it may be that a rules-based approach with China will have more currency in some contexts than others. Chinese officials bristle at American calls for China to “play by the rules” at the same time that U.S. officials proclaim that the United States and its like-minded partners will be the ones to “write the rules of the road for the twenty-first century.” Skepticism about China’s approach to rules for conflict prevention should encourage further analysis of the possibilities and limitations of rules in other spheres of China’s foreign affairs.

Humility and Hope for Rules-Based Stability

China’s approach to rules of the road in risk reduction and deescalation has central importance in some of the most dangerous arenas of U.S.-China relations today: tensions around Taiwan, the South China Sea, East China Sea and cyberspace, among others. Dialogue over guardrails is not a mere distraction to be avoided in order to focus single-mindedly on competition. But to more convincingly make the case to China about the need for stronger rules to manage bilateral competition, U.S. policymakers should be attuned to Chinese perceptions regarding the asymmetry of rules.

Arguments that “time is on China’s side” could undermine this objective by telegraphing that Washington thinks Beijing can probably get a better deal for itself if it holds out. It would behoove U.S. officials to dispense with that assumption—not because it is necessarily wrong, but because it is analytically unhelpful.

As Hal Brands and Michael Beckley have argued, it may well be the case that China’s power has peaked, and going forward it will face a daunting combination of economic headwinds and a coalition of determined foreign rivals. For Brands and Beckley, this is a deeply troubling scenario because it is in these circumstances when “a revisionist power may act boldly, even aggressively, to grab what it can before it is too late.” Applying their analysis to China, Brands and Beckley conclude that “China probably won’t undertake an all-out military rampage across Asia, as Japan did in the 1930s and early 1940s. But it will run greater risks and accept greater tensions as it tries to lock in key gains.”

It is therefore plausible that China’s risk tolerance is not strictly dependent on its power trajectory. Chinese leaders may view the absence of clear rules, communication channels and arms control arrangements as a form of strategic ambiguity that works in its favor in an international environment that is likely to be hostile regardless of whether China is on the brink of hegemonic ascent or secular stagnation. The question then is less about whether putative rules are in the objective self-interests of Washington and Beijing than about whether decision-makers on each side perceive the rules as being in their interests. “Getting to yes” requires persistent efforts at negotiation and persuasion. It may also require experimenting with new approaches.

For example, bilateral negotiations might not be the most fruitful forum for seeking to influence Chinese perceptions regarding the stabilizing value of deescalation rules and protocols. A multilateral process, with a less direct stakeholder such as the European Union playing a convening role, might stand a better chance at helping participants overcome divergences in their views. That outcome is far from assured, and even if such a process succeeded in reducing the risk of military conflict, it could not be expected to resolve deeper tensions in U.S.-China relations. Still, the imperative to prevent accidental war makes a new dialogue structure well worth considering.

Whatever the forum, U.S. officials should enter discussions on rules of the road free of determinism about China’s future trajectory and fortified by a willingness to rethink assumptions that their Chinese counterparts do not share.

-(1).jpeg?sfvrsn=70dcd68a_9)