Revelations on the FBI’s Unlocking of the San Bernardino iPhone: Maybe the Future Isn't Going Dark After All

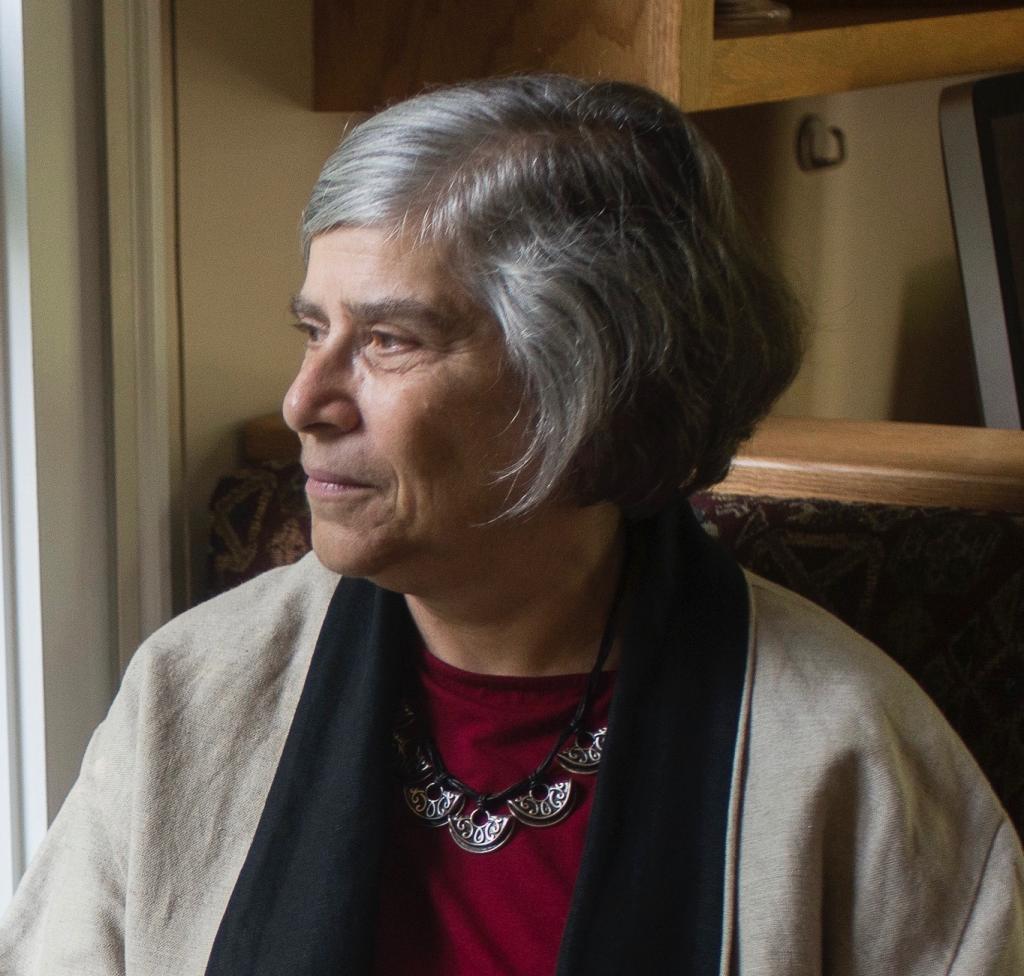

Lawfare readers may be familiar with the San Bernardino case in which the FBI took Apple to court over the locked iPhone of the dead terrorist. I certainly am. I testified in Congress about the case in March 2016 and recently published a book on whether law enforcement should have exceptional access to locked devices. (Short answer: no).

Lawfare readers may be familiar with the San Bernardino case in which the FBI took Apple to court over the locked iPhone of the dead terrorist. I certainly am. I testified in Congress about the case in March 2016 and recently published a book on whether law enforcement should have exceptional access to locked devices. (Short answer: no). I have also written extensively for Lawfare on the issue. Through it all, I've avoided saying that the FBI was just waiting for something like the San Bernardino case to come along; that felt too cynical. But a Justice Department inspector-general report issued on March 27 makes such cynicism seem mild.

Recall that the government took Apple to court over the issue of helping to unlock the iPhone in question. The government sought an order compelling Apple to write a software update undoing the security protections Apple had built into the iPhone 5c. These included eliminating the limit of ten PIN tries to unlock the phone—after that, the phone’s data would be erased—and speeding up the ways the PINs could be entered. Apple opposed the order, arguing that such code would undermine the security of all iPhones and that the government lacked authority to require the company such a complex piece of software. Over the next six weeks, the battle played out in the courts—and the court of public opinion—until the government suddenly announced that it had found a way into the phone and would not need Apple’s help.

This fight had been looming ever since Apple introduced security improvements to iOS 8 preventing anyone who lacked knowledge of the device’s PIN from extracting data from the phone. This was a security improvement for device owners. But law enforcement, which had grown increasingly to rely on mobile devices for evidence, viewed this development not as a security improvement, but as law enforcement “going dark” during investigations. Law enforcement was prepared for a fight over the issues, and the San Bernardino case gave it to them. As Amy Hess, who was the assistant director of the FBI's Science and Technology Branch in 2014, accurately described the bureau’s problems opening the San Bernardino shooter’s phone as “the ‘poster child’ case for the Going Dark challenge.”

Except it wasn’t. The recent IG report presents the FBI’s failure to open the phone not as technical inability to do so, but rather as a result of lackluster effort, and, in one crucial instance, a clear unwillingness to fully search for a solution.

The IG report was motivated by Hess’s concerns about whether the FBI’s presentation of the case was accurate. Hess and FBI director James Comey testified to Congress that the FBI could not open the phone, and U.S. attorneys went so far as to apply for a court order compelling Apple’s assistance. Even as the U.S. attorney’s office was filing its motion to require Apple to build software unlocking the iPhone, Hess sensed she was not “getting a straight answer to the question whether [the FBI’s Operational Technology Division] had any way of getting into the phone.” She pressed harder, and a month later, through one of its contractors, the FBI opened the phone. The IG report shows that Hess’s initial concerns were justified.

For the FBI, the IG report brings some good news: No one deliberately withheld knowledge to prevent opening the locked iPhone. But that's about the only positive revelation. The IG report chronicles foot dragging during the efforts to open the locked device and, in a critical instance, an aversion to finding a technological resolution of the issue outside of the court case. Above all, the IG report casts doubt on the argument that locked phones are "warrant-proof" devices preventing law enforcement from doing its job.

The FBI’s failure to open the iPhone was a result of bureaucracy and slowdown. Two units of the FBI's Operational Technology Division (OTD) were key to eventually unlocking the iPhone: the Cryptologic and Electronic Analysis Unit (CEAU), which examines data on digital devices, working largely on criminal cases, and the Remote Operations Unit (ROU), which uses network exploitation techniques and appears to work largely in classified cases.

San Bernardino was treated as a criminal case. CEAU began work on the iPhone but couldn't unlock the device. Thus, on Feb. 9, 2016, Comey testified to Congress that "We still have one of those killers' phones that we have not been able to open. It's been over two months now. We're still working on it." The IG reported that at that point, no one had asked ROU to help open the phone. The IG report also explained that the ROU unit chief had not volunteered. He had been operating under the mistaken belief that ROU's classified techniques could not be used in criminal cases; as a result, the unit chief had not reached out to CEAU about potential solutions.

Hess was concerned that she was not getting a forthcoming response about OTD's ability to open the phone. She was right. Two days after Comey's congressional testimony, at an a OTD monthly meeting, the CEAU chief asked the ROU chief about capabilities for unlocking the phone (Hess's inquiries may have prompted this outreach). Things finally began to move. The ROU chief reached out to his vendors, and on March 16, 2016, discovered that one of them was already 90 percent of the way toward a solution. At the FBI's request, the vendor reallocated resources, moving work on opening the iPhone "to the 'front burner.'" A month later, a vendor demonstrated a solution to the FBI, and the court conflict between Apple and the FBI was over.

Opening the locked iPhone should have been a good within the FBI. But that was not the view held by the CEAU chief; he apparently asked the ROU chief, "Why did you do that for?" The CEAU chief told the Inspector General "after the outside vendor came forward, [the CEAU chief] became frustrated that the case against Apple could no longer go forward."

That's a striking story. We have the FBI director testifying—and U.S. attorneys submitting a motion operating of of the same premise—that only Apple could unlock this terrorist's phone. But it seems that what was really going on, at least on the part of some FBI investigators, was an unwillingness to really try.

What the FBI stood to receive from a court decision might explain this unwillingness. The FBI sought not just a tool to open the single iPhone in question but something much more stronger—and much more risky. The FBI wanted Apple to create an iPhone update that would make it easy for agents to try as many PINs as needed to open the phone. In other words, the FBI was asking Apple to build a tool that would open any locked iPhone, not just the San Bernardino terrorist’s. Such a tool would make all iPhones less secure.

Exposing the “going dark” story to bright light, the IG report shows that in the high profile case of the San Bernardino terrorist, the FBI failed to use all the capabilities the bureau had at its disposal. The FBI's difficulty with opening the iPhone—and its recourse to court—occurred because the FBI simply didn't try hard enough. Instead the FBI went to court, asking Apple to fix law enforcement's problem. The report cites poor communication and coordination within the OTD, a misunderstanding of when classified capabilities could be used in criminal cases, and a CEAU unit chief who sought to use legal pressure rather than investigative techniques to open the phone.

From the start, the FBI argued that Apple’s new security protections undermined public safety. It appears that the CEAU unit chief sought to use a “poster child” case to force Apple into building tools that would undo those protections. Yet, the premise of the going dark thesis is not nearly as strong as law enforcement would make out. Recent news shows that despite Apple's continuing efforts to secure phones, there are ways to open these locked devices. Forbes recently reported that the Israeli company Cellebrite claims to be able to open all models of iPhones, and that a new U.S. startup, GrayKey, makes similar claims. It seems that we're not going dark—or at least not nearly to the extent that FBI director Christopher Wray, Manhattan district attorney Cyrus Vance Jr., and Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein have claimed.

My conclusion? It hasn’t changed since my 2016 House testimony:

We need twenty-first century technologies to secure the data that twenty-first century enemies—organized crime and nation-state attackers—seek to steal and exploit. Twentieth century approaches that provide law enforcement with the ability to investigate but also simplify exploitations and attacks are not in our national-security interest. Instead of laws and regulations that weaken our protections, we should enable law enforcement to develop twenty-first century capabilities for conducting investigations.

Everything I've learned about since then—including current technological capabilities within law enforcement, the Russian activities during the 2016 presidential election and increasing threats to civil society—makes that case, if anything, stronger than it was two years ago. And as for the problems the FBI had with the iPhone in the San Bernardino case, the IG report makes it clear that that was a failure to fully explore investigation options before going to court. It was not a “going dark” issue.