REvil Is Down—For Now

What can be learned from the operations that got them to shut down?

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The U.S. government and an undisclosed foreign partner have taken a major step forward in the fight against ransomware. On Monday, Nov. 8, the Justice Department unsealed indictments against two ransomware criminals connected to the Russian-speaking ransomware gang REvil and announced that it had recovered an estimated $6 million in ransomware payments collected by the gang. In conjunction with the Justice Department’s announcement, the Treasury Department announced new sanctions against the REvil hackers and Chatex, a major cryptocurrency platform that ransomware hackers use to facilitate the payment of ransoms. At the same time, the State Department announced a bounty program offering up to $10 million for information about REvil’s leaders. To top off the flurry of activity, Europol, Europe’s law enforcement agency, announced that it worked with local law enforcement in Romania and Kuwait to arrest five hackers linked to REvil, including one of the individuals named in the Justice Department’s indictment.

Collectively, these actions strike a significant blow to REvil, which was responsible for the June ransomware attack against the meatpacking company JBS and the July attack against the U.S. software firm Kaseya that spread malware to hundreds of organizations worldwide. The government’s campaign against REvil, however, has been months in the making, involving several coordinated campaigns by U.S. and foreign intelligence agencies. The first domino in the chain reaction that led to the recent headlines fell earlier this year when an allied foreign intelligence agency successfully hacked REvil’s servers. Signs of trouble within REvil’s ranks began to surface in mid-October when REvil disappeared offline after discovering that their servers had been hacked.

In terms of the United States’ longer-term fight against cybercrime, the specifics of the offensive campaigns that culminated in REvil’s disappearance—and, ultimately, in the indictments—are just as important as the outcome itself. As one of us argued recently in an op-ed for the New York Times, neither defensive nor deterrence measures alone will allow the U.S. to effectively resolve the ransomware problem. Instead, the U.S. needs to go on the offensive—and the success of the recent campaign against REvil demonstrates why.

The series of operations began earlier this year, when an undisclosed foreign partner covertly hacked REvil’s servers, likely as part of an intelligence collection operation. The operation gathered important information about REvil’s operations, including REvil’s decryption key, which the FBI later provided to Kaseya to pass on to their impacted customers. The operation and the Washington Post’s coverage of it in September apparently went unnoticed by REvil at the time.

Shortly after the Kaseya attacks, one of REvil’s members, who goes by the nickname “unknown,” suddenly went offline without any forewarning or explanation. As REvil explained in an October blog post, the group decided to voluntarily take itself offline in July while they tried to figure out whether unknown’s disappearance had been caused by possible law enforcement action against the group. After lying low for several months without hearing from unknown—the group later explained that they presumed he had died—REvil resumed their operations in September.

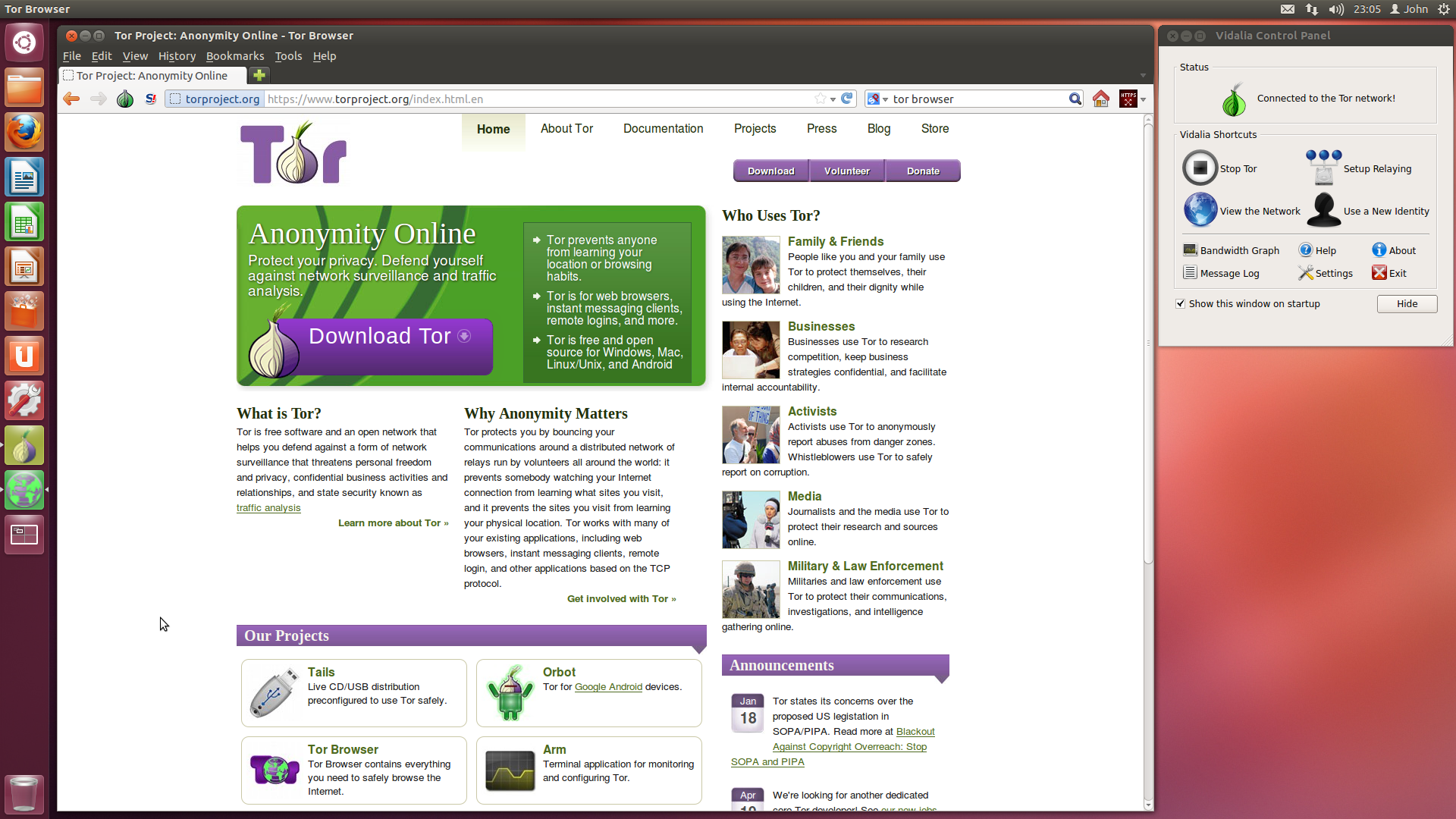

With REvil back online, Cyber Command used the intelligence gleaned from the foreign partner’s July hack to launch a disruption operation against Happy Blog, a Tor site that REvil used to post the names of their victims to extort them to pay a ransom. Using the separate Tor private keys obtained during the earlier operation, Cyber Command successfully cloned the Happy Blog Tor site, essentially creating a collision between two sites on the Tor network that denied users the ability to access the Happy Blog—an effective denial-of-service operation.

In many respects, what happened next was unique in the history of cyber offensive operations. While the Cyber Command’s campaign was taking place, an REvil leader who posts under the username “0_neday” was broadcasting their reactions to the operation in real time on a hacker forum that REvil uses to communicate with affiliates. This commentary gives the clearest insight that security researchers have ever received into the thought process of a ransomware criminal who is the target of an offensive operation, and it unambiguously demonstrates what kinds of tactics succeed in pressuring ransomware criminals to end their operations.

Following the Cyber Command operation, REvil noticed a disruption that caused them to realize that their Tor keys had been stolen. In response, the group decided to go through its servers to look for signs of compromise, but as they reported that day, a sweep of their servers didn’t turn up any evidence of a compromise. The group continued working with their affiliates to distribute decryption keys to victims who had paid their ransom. But a day later, the group checked its servers again, this time discovering signs of the July compromise that they had initially overlooked. Realizing that whoever had hacked them may have retrieved identifying information about its members, REvil panicked, immediately shutting down its operations. “Good luck everyone,” wrote 0_neday on the forum shortly before REvil went offline. “I’m taking off.”

What lessons can be drawn from these two operations and their success—at least for now—in driving REvil offline? It’s too simplistic to say that offensive cyber operations work. While disruption campaigns are certainly helpful in obstructing ransom groups’ day-to-day operations, Cyber Command’s offensive campaign alone was evidently not sufficient to prompt REvil to go offline. What that operation appears to have done is to alert the group that their Tor keys had been stolen, triggering their ultimate discovery of the earlier covert intrusion. Ironically, it was REvil’s discovery of that intrusion—which the foreign partner had gone to some lengths to hide—that finally prompted them to go offline.

In retrospect, the reason why is obvious. What all criminals—cyber or otherwise—fear most is losing their liberty after being discovered and arrested. In this case, 0_neday’s statement that “they are looking for me” tells us everything we need to know about ransomware criminals’ psychology: The credible threat of losing their freedom and money outweighs the unrealized benefits of continued criminal activity, especially if the criminals in question have already earned millions of dollars in illicit gains.

The U.S. government and its allies should continue to conduct anti-ransomware campaigns that leverage this fear. Bounties for information that lead to the discovery or arrests of hackers—like the ones announced by the State Department in recent weeks—are critical, since they increase the levels of paranoia among the criminal community. The large bounties promised by these campaigns—up to $10 million in the case of the State Department’s latest one against REvil—send a clear message to hackers: You are being tracked down, and no one in your circle, not even your closest friends and family, can be trusted. Similarly, campaigns that signal to criminals that intelligence services are watching them are a highly effective way of putting psychological pressure on ransomware criminals. Imagine, for instance, that a criminal receives a text from an unknown phone number with a copy of their passport, their upcoming travel itinerary and their home address. This sort of operation will drive even the most sophisticated gangs to pack up their operations for good.