The Rise of Ballot Drop Boxes Due to the Coronavirus

Some states have successfully used ballot drop boxes for years, but the coronavirus pandemic has expanded the practice throughout the United States.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Lawfare is partnering with the Stanford-MIT Healthy Elections Project to produce a series on election integrity in the midst of the coronavirus crisis. The Healthy Elections Project aims to assist election officials and the public as the nation confronts the challenges that the coronavirus pandemic poses for election administration. Through student-driven research, tool development, and direct services to jurisdictions, the project focuses on confronting the logistical challenges faced by states as they make rapid transitions to mail balloting and the creation of safe polling places. Read other installments in the series here.

The absentee ballot drop box is an increasingly popular option for voters to submit completed mail ballots to election officials without using the mail. While some states have successfully used ballot drop boxes for years, the coronavirus pandemic has expanded the practice throughout the United States, particularly as election officials have expressed concern about the U.S. Postal Service’s (USPS’s) capacity to reliably deliver absentee ballots on time. Although some states, such as Tennessee, still prohibit the use of ballot drop boxes, citing risk of voter fraud without clear evidence, at least 34 states have used or plan on using ballot drop boxes this year. In the upcoming election, the use of drop boxes will likely be larger than in any election in American history.

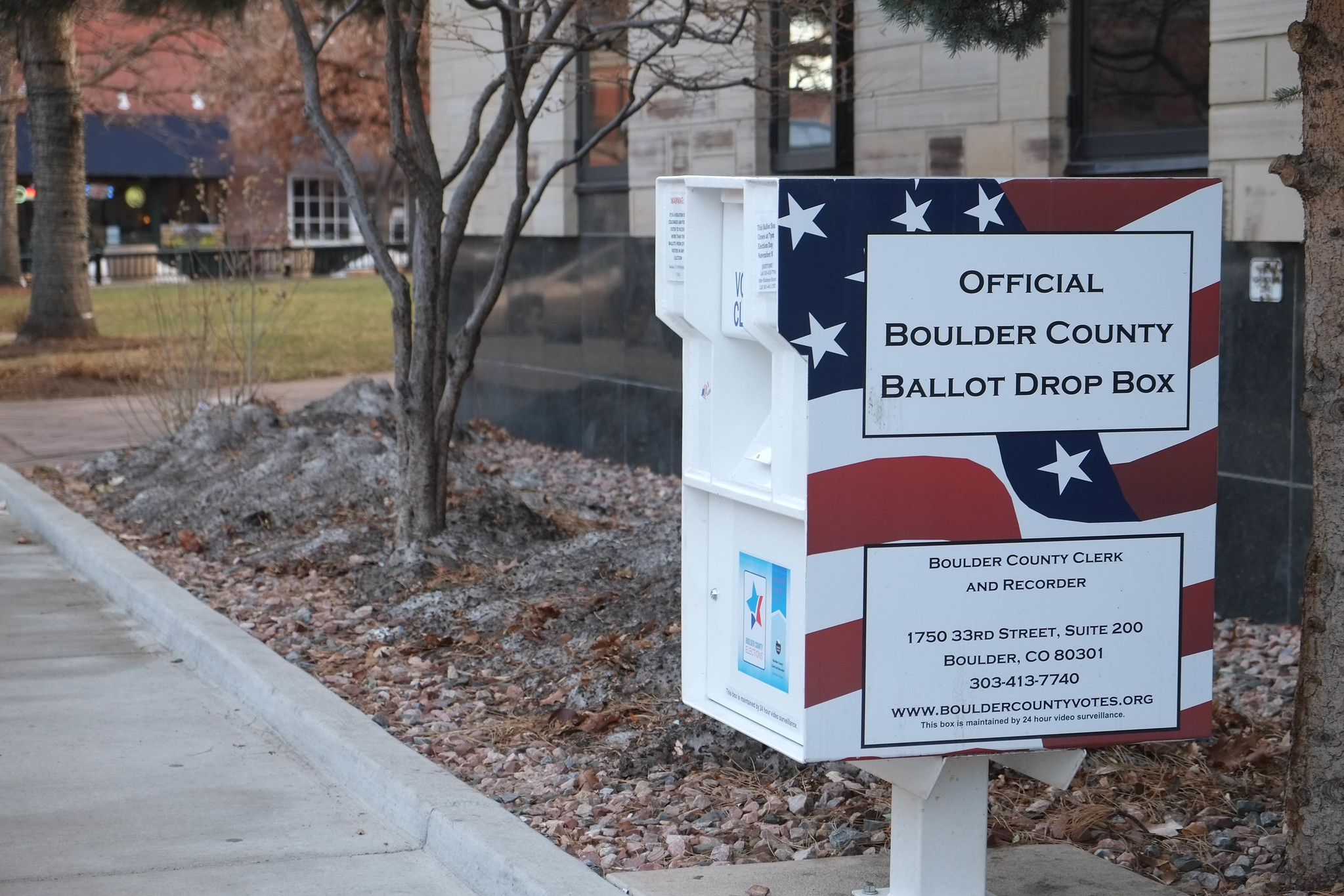

During the 2016 general election, nearly one in six voters nationwide cast their ballot using drop boxes, and this figure will likely rise in 2020. Ballot drop boxes are secure, locked structures that allow voters in many states to cast completed absentee ballots without relying on the USPS for delivery. According to the Election Assistance Commission (EAC), some voters prefer ballot drop boxes to mail delivery due to “concern[s] about meeting the postmark deadline and ensuring that their ballot is returned in time to be counted.” Many states, for that reason, offer voters the option to drop off absentee ballots up until Election Day. Drop boxes come in one of two forms: either staffed, indoor drop-off locations or unstaffed, outdoor boxes that are locked, anchored, tamper-proof, and often monitored by 24-hour video surveillance.

In some states, ballot drop boxes have been implemented successfully for years and serve as a popular option for many voters. In Colorado, for example, nearly 75 percent of all voters in the 2016 general election cast their ballots using a drop box. In Washington state, ballot drop box usage rates have also increased over time, from 37.7 percent overall in the 2012 general election to 56.9 percent in 2016. In other states, however—especially those without a history of robust absentee voting—the use of ballot drop boxes is in its infancy or nonexistent. Yet, due to the coronavirus, an increasing number of states have ramped up their use of ballot drop boxes in order to give voters the option to vote without risking coronavirus transmission in person or potentially overwhelming the USPS with mail-in votes.

Our full report on ballot drop boxes can be found here.

Drop Box Usage by State

The National Conference of State Legislatures reports that only eight states—Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon and Washington state—explicitly permit or require ballot drop boxes by statute or regulatory guidance. In practice, however, many more states use ballot drop boxes regularly, either through statewide practice (without specific statutory language) or on a county-by-county basis. According to the Brookings Institution, “[d]rop-off boxes, mail, and in-person channels” to vote are available in at least 16 states as of Aug. 15, including Alabama, Alaska, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, Nebraska, Ohio and Utah, as well as Washington, D.C.

Many more states do not offer ballot drop boxes statewide but have implemented the drop box model in one or more counties or cities, including Illinois (in Chicago), Iowa (in Cedar Rapids and Marion), Kansas (in Sedgwick County), Maine (in Bangor), Minnesota (through a drive-through ballot drop off in Minneapolis), Nevada (in Clark County), Pennsylvania (in Philadelphia and several counties, pending recent litigation), South Carolina (in Charleston County), South Dakota (in Lincoln County), Virginia (in Arlington) and Wisconsin (in Milwaukee County, Sheboygan County and many cities). Many other states have implemented new ballot drop box systems since the start of the pandemic, including Connecticut, Kentucky, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Dakota and Rhode Island.

Altogether, at least 34 states (and Washington, D.C.) have used or plan on using ballot drop boxes in one or more locations in 2020. And a few more states, including New York, have pending legislation that may lead to the implementation of drop boxes before November’s general election.

By contrast, four states have explicitly disallowed the use of ballot drop boxes in the upcoming elections. Tennessee, for example, will not allow drop boxes due to concerns of fraud. Tennessee’s Secretary of State Tre Hargett cited without evidence the risk of individuals illegally dropping off ballots on behalf of other voters. “We believe it’s a great security measure to have someone returning their own ballot by the United States Postal Service,” he said. Similarly, New Hampshire will not allow voters to leave a ballot at town or city hall drop off boxes after hours; ballots must be either mailed in or hand-delivered directly to an election official. Missouri’s secretary of state also chose not to distribute the 80 drop boxes the state had purchased because state law requires ballots to be returned by mail. Finally, although more than one-third of Iowa county auditors provided ballot drop boxes during the state’s June primary and in previous elections, Iowa’s secretary of state will no longer allow counties to set up ballot drop boxes for November’s election. Instead, a spokesperson for the secretary of state said that election officials will only be permitted to set up a “no-contact delivery system for voters in their office to use during regular business hours.”

At least 34 states have used or plan on using ballot drop boxes in one or more locations in 2020, while just four states explicitly prohibit the practice. Credit: Created by author using mapchart.net

Ballot Drop Box Types

Three types of ballot drop boxes are typically used during early voting and up until Election Day.

- Indoor, Temporary Ballot Drop Boxes: These boxes are staffed and monitored by election officials, available during regular business hours, and located in various buildings known to voters, such as county and city office buildings, other government facilities, early voting locations and Election Day voting sites. Some states, such as California, allow voters to bring their completed absentee ballots to a polling place on Election Day and drop them off at a designated drop box. This often lets voters bypass in-person voting lines and reduces overall wait times.

- Outdoor, Temporary Ballot Drop Boxes: These drop-off sites are usually staffed drive-through locations that allow voters to quickly give officials their completed ballots “when demand for a ballot drop box is at its peak, especially on Election Day,” according to the EAC. These sites are also generally accessible to voters on bikes as well as walkers. Minneapolis created two such locations during Minnesota’s August primary in order to help keep voters socially distant and to ease in-person lines on Election Day.

- Outdoor, Permanent Ballot Drop Boxes: These boxes are unstaffed, secure structures placed in high-visibility and high-demand areas, such as locations near public transportation, college campuses and public buildings (including community centers and libraries). The EAC recommends that these boxes be placed in well-lit areas that are accessible to voters. In addition, the EAC notes that unstaffed boxes should be durable (constructed from steel or other strong materials), permanently bolted into the ground and built to be tamper-proof. These drop boxes are also sometimes used for multiple purposes, such as collecting tax and public utilities payments at other times of the year. In Madison, Wisconsin, for example, the city successfully converted public library book return boxes into secure absentee ballot drop boxes after the coronavirus shut down the city’s libraries.

The Safety and Security of Ballot Drop Boxes

Ballot drop boxes generally weigh more than 600 pounds and are built to be more secure than the typical USPS mail box. For example, an SUV in Washington state crashed into one such box last year, but both the box and its contents survived. They are also typically weather resistant and fire suppressant. The tamper-proof mechanisms vary by manufacturer, but they often include special locks to prevent opening, as well as tamper-evident seals and one-way entrance slots. In addition, the EAC recommends that permanent ballot drop boxes be equipped with video monitoring technology or, if not feasible, be positioned close to a nearby security camera or monitored by local law enforcement. As such, ballot drop boxes are extremely safe against misuse.

A ballot drop box in Lane County, Oregon, 2006 (Chris Phan/https://flic.kr/p/qsq2m/(CC BY-SA 2.0/https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/)

Given their utility and high demand, permanent ballot drop boxes typically cost about $6,000 each and, if custom made, may need to be ordered four to six months before an election. Even after manufacturing, the deployment process itself can take up to eight weeks due to installation time and the time needed to acquire necessary security equipment. Manufacturers for these boxes include Vote Armor, Ballot Drops and Kingsley.

Drop Box Best Practices

The EAC recommends that election officials install one drop box for every 15,000 to 20,000

registered voters. Additional drop boxes should be added to areas with historically low rates of vote-by-mail usage, and counties should consider using demographic data and altering the placement formula based on the different needs of urban and rural regions. When deciding where to place new ballot drop boxes, officials can use the U.S. Census Bureau Interactive Workforce Map and other governmental data to best position drop boxes where voters live, work and travel on a typical day.

Due to concerns about the integrity of the ballot delivery process from drop boxes to election officials, the EAC also recommends that bipartisan teams be positioned at every ballot drop box when polls close and that every state and county establish a “chain of custody” plan to ensure that the movement of all ballots is logged and can be tracked at all times. In Connecticut, for instance, clerks empty drop boxes for delivery to other election officials several times a day throughout the Early Election period, and in the days before Election Day, officials emptied boxes every hour in Hartford to avoid overflow and ensure timely delivery of absentee ballots.

Several states with a history of vote-by-mail and ballot drop boxes provide additional best practices. Pierce County’s auditor in Washington state, for example, recommended in 2014 that counties open ballot drop boxes at the start of Early Voting, use daily pick-ups to track the frequency of use, and train election officials and political party observers on all relevant ballot drop box procedures. The auditor also advised election officials to use a “website, local voters’ pamphlet, and ballot inserts to inform voters of box locations,” noting that counties can also create an interactive online map with photographs, driving directions and deadline reminders for all votes.

The Legality of Third Parties Delivering Ballots

During the coronavirus pandemic, some voters—especially individuals at risk for severe illness—may wish to designate someone else to deliver their ballot to a drop box on their behalf. The legality of third parties delivering ballots into drop boxes varies widely by state, however.

As of March 2020, 27 states allow absentee ballots to be returned by a designated agent, which can be a family member, care provider or attorney; nine states allow an absentee ballot to be returned by a voter’s family member; 13 states do not explicitly address this issue; and one state, Alabama, specifies that no one other than the absentee voters themselves may return their ballots. A full list of state requirements can be found on the NCSL website.

The Rise of Drop Boxes in 2020 Due to the Coronavirus

During the pandemic, several state legislatures and governors have expanded the use of ballot drop boxes for November’s general election:

- Michigan election officials recommended that voters use drop boxes instead of the USPS during its August primary due to mail delivery backlogs that risked invalidating late deliveries. The state now has more than 750 ballot drop box locations, most of which are 24/7, outdoor fixtures. As part of its expansion, Michigan used $2 million of its federal CARES Act funding “for cities to buy additional equipment to make obtaining and processing absentee ballots easier, such as ballot drop boxes, high-speed counting machines and automatic letter openers.”

- Georgia installed 144 absentee boxes through a statewide grant program, which allows counties to apply for $3,000 to offset 75 percent of the cost of new ballot drop boxes. Georgia’s secretary of state, Brad Raffensperger, “encourage[s] every county to take advantage of the grant program and install a drop box ahead of the November elections.”

- New Jersey state officials announced that at least 105 more drop boxes would be added before November.

- Connecticut installed around 200 drop boxes with CARES Act funding in time for the Aug. 11 primary.

- Kentucky’s 2020 general election plan includes the use of ballot drop boxes for the first time, with each county’s drop box locations to be decided by the respective county clerk.

- New Mexico is launching a pilot program to use ballot drop boxes for the general election.

- North Dakota allowed voters to return ballots via drop box during the June primary, but voters were required to contact their county auditor for drop box locations.

- Maryland’s state elections administrator requested $40,500 in additional funding from the state to purchase additional ballot drop boxes.

- Rhode Island’s Board of Elections authorized drop boxes for the June 2 primary in all 47 polling places and at the 39 Board of Canvassers locations, one of which is located in each city or town hall.

- Louisiana’s secretary of state has taken steps to limit vote-by-mail options but nonetheless has proposed curbside drop-off options for absentee ballots.

In other states, the use of ballot drop boxes during the 2020 general election has been more

controversial. In Ohio, after a recent directive by Secretary of State Frank LaRose, each county will be permitted to have only one ballot drop box. This limitation has raised ballot access concerns, particularly for voters without cars. For example, Delaware County’s sole drop box is behind the county’s Board of Elections building, 2.5 miles away from the city of Delaware and “nowhere within walking distance of the city’s residents.” LaRose claims that he does not have the legal authority to expand drop box locations without legislative action, but Ohio’s Democratic chairman, David Pepper, says that the secretary of state has “spent the last month doing everything he could to stop drop boxes, delaying it for almost a month, and then unilaterally only saying one per county without a legal opinion.”

A bicyclist drops off California 2014 primary election ballot in a ballot drop box (George Kelly/ https://flic.kr/p/nT8Cbx/CC BY-ND 2.0/https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/)

Recent Litigation Over Ballot Drop Boxes

During the June 2 primary election in Pennsylvania, the city of Philadelphia installed 11 ballot

drop boxes around the city, and about 20 counties introduced drop boxes to ease the burden of a surge in mail voting. Since then, the Trump reelection campaign has sued Pennsylvania in federal court, arguing that the use of ballot drop boxes during the primary was unconstitutional and asking the court to bar their use in the general election. The complaint alleges that “inadequately noticed and unmonitored ad hoc drop boxes” and “the lack of statewide standards governing the location of drop boxes” violates the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The suit also claims that drop boxes “have increased the potential for ballot fraud or tampering” and that the state’s mail-in voting system “provides fraudsters an easy opportunity to engage in ballot harvesting, manipulate or destroy ballots, manufacture duplicitous votes, and sow chaos.”

A federal judge ordered the Trump campaign to produce evidence of voting fraud occurring via drop boxes. After the Trump campaign “failed to produce any evidence of vote-by-mail fraud in Pennsylvania,” the judge put the case on hold pending resolution in Pennsylvania state court. President Trump has also recently tweeted concerns about ballot drop boxes, alleging that they “make it possible for a person to vote multiple times” and are a “big fraud,” but Twitter has since placed a public interest notice on the tweet for violating its civic integrity policy by “making misleading health claims that could potentially dissuade people from participation in voting.”

Conclusion

Due to a combination of coronavirus safety concerns, an increase in expected absentee voting generally, and more recent questions about the capability of the USPS to deliver all absentee ballots in a timely manner, the use of ballot drop boxes during the 2020 general election will likely be larger than in any election in American history.

- As states and counties prepare for an influx in absentee ballot requests and look for various avenues to reduce potential backlogs of incoming mail-in ballots, ballot drop boxes are a viable option for many states and voters. Still, states must recognize the time it takes for manufacturers to produce and deliver these boxes, the importance of voter outreach and education about new drop box options, and the potential risk of future litigation.