'Riyadhology' and Muhammad bin Salman’s Telltale Succession

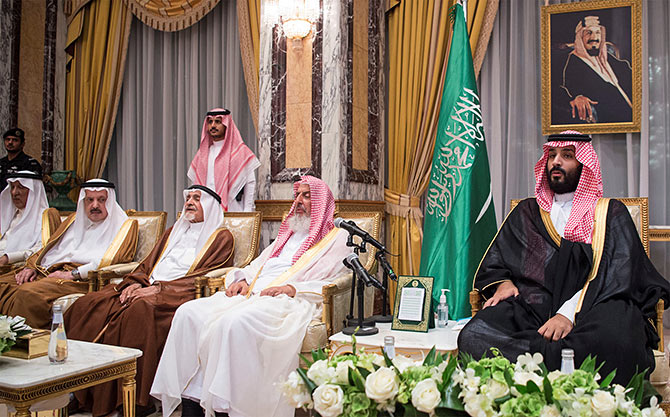

Saudi Arabia’s monarchy entered a new era last June when King Salman’s ambitious son Muhammad bin Salman, then just shy of 32, was made crown prince by royal order. MBS, as he is widely known, displaced Muhammad bin Nayef, an influential prince with deep ties to Washington, as next in line to the throne, marking a shift from the aging sons of the country’s founder, ‘Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud, to a younger coterie of royals—and skipping the generation in between.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Saudi Arabia’s monarchy entered a new era last June when King Salman’s ambitious son Muhammad bin Salman, then just shy of 32, was made crown prince by royal order. MBS, as he is widely known, displaced Muhammad bin Nayef, an influential prince with deep ties to Washington, as next in line to the throne, marking a shift from the aging sons of the country’s founder, ‘Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud, to a younger coterie of royals—and skipping the generation in between. Since even before his accession to crown prince, MBS promoted a dynamic agenda of economic and social reforms—with plans to diversify the country’s economy, expand women’s rights and grant greater openness to Western culture—while also cracking down on political dissent.

There are different ways to try to decipher the political intrigue among the Saudi royal family. Among the best available tea leaves are the Saudis’ own legal pronouncements, and the royal orders that brought MBS to his current position are telling. Clearly rushed and poorly vetted, they suggest that King Salman and MBS were working outside the normal process for consensus within the royal family and that there is significant opposition to MBS’s rule waiting in the wings.

Otherwise dry Saudi legal texts tell us much about "Riyadhology"—the Saudi equivalent of Kremlinology in the days of Soviet signal opacity. Laws of social science are more elusive, but I have defended the concept of "constitutional science" against skeptical editors, and sometimes prevailed. If one looks closely enough at key constitutional clauses, the wording reveals a compromise of political powers, each trying to push the language to his advantage. This is trite. More daring is the proposal that the fractured logic of these texts can give clues about a coming crisis.

When MBS was appointed crown prince in June 2017, the irregularities in the official process portended trouble. At stake is the transition of power from King Salman to his son.

MBS’s elevation to crown prince was already peculiar in that it bypassed many more senior princes in the royal line. The traditional system predicts passage of the crown to the next brother by gerontocracy’s limits. King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz sired at least 45 sons (some references say 53). Six of them became kings; the last is Salman, who took over from Abdullah in January 2015. His brother Muqrin, who was still relatively young at 70, became crown prince. He was replaced by Muhammad bin Nayef three months later "on his request." The first oddity about the selection of MBS was that Muqrin had 13 other relatively able brothers; the horizontal system of succession was broken by naming a member of the next generation as successor.

A second oddity was the other law pronounced on June 21, 2017. The Basic Law of Government—enacted by King Fahd in 1992 and the closest legal instrument Saudi Arabia has to a constitution—discusses succession under Article 5b: “The dynastic right shall be confined to the sons of the Founder King Abdul Aziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud (Ibn Saud), and to the sons of sons. The most suitable among them shall be invited, through the process of bay‘a to rule in accordance with the Book of God [the Qur’an] and the Prophet’s Sunnah," as the Prophet Muhammad’s sayings and deeds are known. After the order declaring MBS crown prince was issued, another short royal order, issued the same day, amended Article 5b of the Basic Law of Government. The constitutional amendment added the following sentence: “There will be, after the sons of the Founder King, no King and Crown Prince belonging to the same branch of the Founder King’s descendants.”

Two things about this amendment are strange. The first is a contradiction: The amendment prevents the king and crown prince from being father and son, but it is supposed to support the royal order designating MBS to eventually replace his father, Salman, as king, even though they both “belong to the same branch of the Founder King’s descendants.” Appointing MBS was an open violation of the amended article. The only explanation is to read the amendment as strictly operative for the future, after MBS takes over—but he will have ample time to issue his own royal orders before his succession becomes relevant.

The second issue is linguistic. The Arabic text, which consists of 17 words, is grammatically deficient. The “King and Crown Prince” it mentions carry a declension, which makes them a direct object instead of subject—a mistake that cannot be translated into English but that is readily apparent (and grating!) to people who use formal Arabic.

Why are these mistakes distinctive? Unlike many Arab republican dictators, whose education is limited, Saudi rulers care for good Arabic. The most significant locus of law-writing is the Council of Experts attached to the Council of Ministers. Their statutory expertise is of high quality. They produce most of the laws in the kingdom, which are then decreed by the king. They were surely not consulted on the amendment of Article 5b. In the thick of the sudden and intense controversy around the promotion of MBS, the mistake went unnoticed. It shows its hurried drafter’s unease to square the apparent commitment to other branches of the family and the absurdity of making an exception for MBS. It could be nastier if deliberate: There is a precedent in a Shiite-Sunni "unity" conclave held in Najaf in 1743. The memoirs of one of the Sunni protagonists, ‘Abdallah al-Suwaydi, show his anger at a similar confusion of declensions made intentionally by a Shiite interlocutor—a mischievous pronunciation of the name of Sunni caliph ‘Umar in his sermon. According to Suwaydi’s handwritten account (a beautiful manuscript held by the British Library), the Shiite cleric subtly used the wrong ending for the name to show that he did not believe in the rapprochement forced by the Persian Shah on the Sunni and Shiite participants in the Najaf conclave.

A third oddity arose from a recent modification to the structure of Saudi royal succession. Whereas acclamation of the new king was traditionally reserved until after the previous king’s death—think of the common monarchic acclamation, “the king is dead, long live the king”—a Law of Bay‘a (best translated here as “succession”) decreed by King Abdullah in 2006 puts his designated successor to a committee vote. The succession committee can legitimately oppose the designated crown prince on the basis of the “most suitable sons” qualification of Article 5b. And when MBS was elevated last June, several members of the committee exercised that right. The royal order marking his appointment mentions that the vote for him was carried “overwhelmingly, 31 out of 34.” (Some press reports at the time mention six committee members opposed him or were non-committal.) Although not enough to tip the scales, the votes against MBS set a remarkable precedent for legal recognition of a formal opposition to the crown prince.

Galileo’s astronomical observations allowed him to predict the position of a planet invisible to the instruments of his time. Neptune was discovered at its expected place in 1845, more than two centuries after Galileo’s prediction. In Riyadhology also, sometimes things can be observed only indirectly. Constitutional science is more imperfect than physics, but the irregularities of MBS’s accession to crown prince—the contradictory pronouncements, poorly vetted language and dissent among the succession committee—tell the tale of a Saudi opposition within the ruling family. In a manner unlikely to have been anticipated in 2006, the 2006 Law of Succession granted legitimacy to opposition within the royal family.

MBS has many potential rivals within the House of Saud. Several members of the family are older and more experienced and therefore have a better dynastic entitlement to succeed King Salman. The three members who "officially" voted against him in June 2017 are unlikely to have stayed inactive. Their names are not publicly known, but a reconstruction by an informed Saudi colleague shows them to be prominent cousins of MBS, as entitled as he is to the crown, and more entitled if the amended version of Article 5b were applied.

There have been hints of open dissent within the family, and the stakes are existential for MBS. Last November, some of the most prominent members of Saudi high society were confined to house arrest at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in Riyadh, including 11 members of the royal family and the most prominent businessmen in the kingdom. Although billed as an anti-corruption crackdown, it certainly looked like the crown prince consolidating his power. Reuters reported at the time that MBS ordered the arrests “when he realized more relatives opposed him becoming king than he had thought.” Eleven other members of the royal family were arrested on Jan. 4.

The young prince is, by all accounts, determined to take over as quickly as possible. His father is 82 and suffers from a mild form of Alzheimer’s. King Salman could change his mind if his unhappy brothers and nephews get his ear. The opposition at large has grown also because of the setbacks of Saudi foreign policy, mostly ascribed to MBS’s impetuous character, in Yemen, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq. His commitment to the glitzy and increasingly elusive 2030 Vision plan has also drawn concern. There was far less money to go around in 2017 and far greater entitlement expected by the ruling family’s proliferating membership, dissenters of all kinds and the population at large. And there is the Arab Spring—the real, nonviolent one on the streets and in social media, which first emerged in preparations for a "Day of Rage" on March 11, 2011, that authorities prevented from being held.

Never has the opposition in Saudi Arabia been so varied and wide. Shiite dissent has been brutally repressed in the eastern provinces. Some 50 people, and the historic Shiite leader Nimr al-Nimr, were executed over the past two years. The Saudi opposition now includes liberals at home as well as abroad. The most prominent among jailed liberal dissenters is Raif Badawi, a young blogger in prison since 2012 together with his lawyer and, in the religious vein, Sheikh Salman al-‘Awdeh, a reformist preacher committed in recent years to "nonviolent (silmi) jihad." He was arrested last September and was held without any charge in solitary confinement. His son, a fellow at Yale Law School, denounced the conditions of his detention upon his transportation to a hospital in January. A "prisoners of conscience" tweet campaign is ongoing—at @m3takl in Arabic and @m3takl_en in English.

The varied dissidence in exile includes the small Washington-based Center for Democracy and Human Rights in Saudi Arabia and the fragmented opposition in London since the flight of one of its historic leaders, Muhammad al-Mas‘ari. I remember meeting Mas‘ari in London in 1994, together with his colleague Saad al-Faqih. A former professor of physics, Mas‘ari was a bit overwhelmed by the attention he received as the first open dissident at the head of an organization called Committee for the Defense of Shar‘i Rights, but the group was probably heavily infiltrated, and its main protagonists fell into disagreement. Other leading, more obdurate dissenters include two female academics. Mai Yamani, the daughter of the sometime celebrated Saudi minister of oil, Ahmad Zaki, published an interesting book on the difference between the dour culture of Najd and the cosmopolitan tradition of a Hijaz smothered by the Wahhabi-Saudi domination since 1924. The works of Madawi al-Rasheed, a prominent academic at the University of London, and the scion of the Rashid ‘tribe’, which the Saudis dislodged from Riyadh in 1902, are the best documented and most wide-ranging. More recently, the respected columnist and news editor Jamal Khashoggi has left the kingdom and become an outspoken critic of MBS’s crackdown on political dissent.

Put all this together and the information shows a large substratum of dissent in Saudi Arabia and a sizable group of significant Saudi personalities living in exile. The history of dissent in Saudi Arabia is getting better known. The opposition is large but remains fissiparous and disorganized. With little support in the West outside prominent human rights organizations, the focus will remain on the domestic opposition. The most significant elements of that opposition lie within the royal family and among the business elite.

The wave of arrests and detentions at the Ritz-Carlton underscored the cracks in the heart of the Saudi establishment. In the official statement, 159 of the most prominent members of Saudi high society were confined to house arrest, including 11 members of the royal family and the most prominent businessmen in the kingdom. The 11 other royals who were arrested this past January were jailed officially for protesting “halted payments by the state (…) to cover their electricity and water utility bills.” A Jan. 6 tweet from @mujtahidd, an anonymous and well-informed Saudi insider account, ascribed the protests to their solidarity with the other members of the family who had been jailed and “humiliated.”

The royals and business leaders opposing MBS are particularly nervous about a far-reaching anti-corruption campaign. Behind the big nab last November stands a revamped Anti-Corruption Committee. Compared with its ineffective predecessor, which issued annual reports of little consequence, the new committee includes the public prosecutor and the head of security and is headed by the crown prince. It was responsible for the arrests and the investigations that filled the Ritz-Carlton. Most of those held were freed two months after their arrest, conditional on their cooperation with an official anti-corruption policy that looked more like a shakedown and yielded, according to press reports, more than $100 billion. "Cleaning up corruption" is a time-worn tool for grabbing power.

A real opening up by the Saudi government put an end to the exactions of the religious police (matawi‘a) in a statute passed in 2016 and would finally allow women to drive and to sit undisturbed with men in cinemas and other public spaces. But repression has continued, its latest expression in the arrest of prominent women despite the promised removal of the ban on women driving. The succession crisis is far from over, and the next big test for MBS is whether he can brook an open, nonviolent opposition.