Robert Mueller’s Sense of Duty Illuminates His Tough Choices

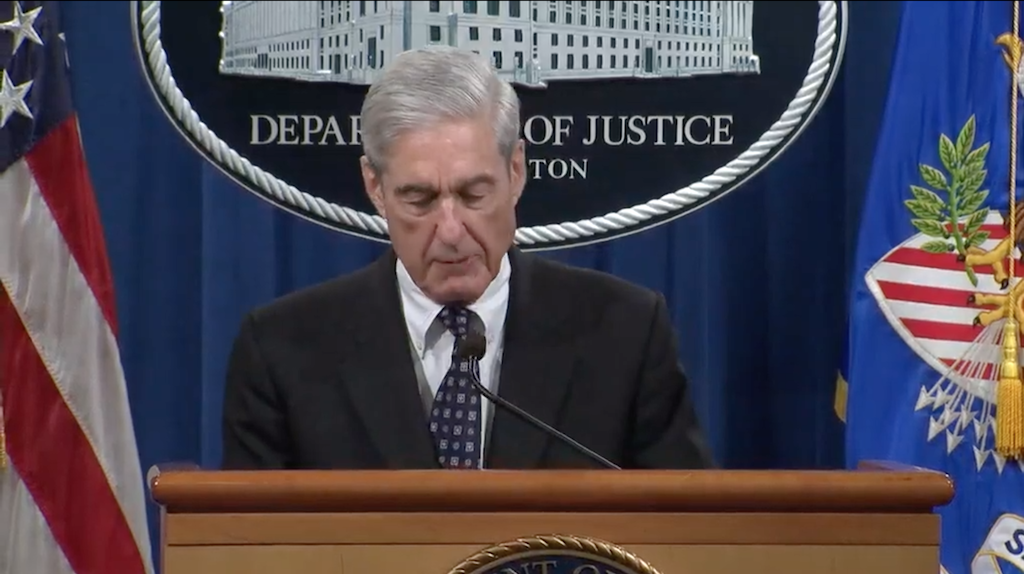

Reactions to former Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s public appearance on Wednesday morning came swiftly, arriving on cable TV panels and social media platforms even before he finished his brief statement.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Reactions to former Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s public appearance on Wednesday morning came swiftly, arriving on cable TV panels and social media platforms even before he finished his brief statement.

The first group of responses breathlessly relayed Mueller’s bottom lines, with his description of his inability under Department of Justice policy to accuse the president of crimes and his declaration of unwillingness to exonerate the president of obstruction of justice treated as breaking news. These conclusions, of course, have been available for almost six weeks, thanks to Attorney General William Barr’s choice to release a redacted version of the Mueller report on April 18. The fact that such statements grabbed headlines immediately after Mueller’s appearance reveals less about the special counsel’s work than it does about how few people—including, apparently, many members of Congress—have made time to actually read the report.

The second set of reactions exploded after Mueller’s expression of his desire to walk away now and leave additional commentary and action to others. “I hope and expect this to be the only time that I will speak about this matter,” he said. “I am making that decision myself—no one has told me whether I can or should testify or speak further about this matter.” The collective sense of abandonment, as expressed most energetically on social media, was palpable. You would have thought Mueller had just announced he was flying to the moon.

But such shock is misplaced. Mueller’s lifetime of public service and his approach to his work as special counsel over the past two years foreshadowed that he would take this approach—remaining within what he understood as his proper lane up to and beyond the end of any assignment, no matter how bumpy the road.

To understand this, it helps to break down Mueller’s choices since the start of his investigation into three categories: things he felt obliged to do, things he felt unable to do and the small category of things in between—which his sense of duty also guided.

First are the set of actions that the special counsel regulations and Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein’s appointment letter required. Specifically, Mueller was tasked to investigate “any links and/or coordination between the Russian government and individuals associated with the campaign of President Donald Trump” as well as “any matters that arose or may arise directly from the investigation” and “any other matters within the scope of 28 C.F.R. §600.4(a).” Mueller did that job straight as an arrow, prosecuting crimes arising from the investigation and referring everything else to other offices.

He also delivered his findings as directed. Not to Congress, not to the American people, not on Twitter—but to the attorney general,as the regulations governing his activity required: “At the conclusion of the Special Counsel’s work, he or she shall provide the Attorney General with a confidential report explaining the prosecution or declination decisions reached by the Special Counsel.” Under the regulations, the decision to make any or all of the report public was not Mueller’s but Barr’s.

And yet there are actions Mueller felt forbidden from taking as a Department of Justice employee. Plenty of attention rightfully has been placed on his strict adherence to the Office of Legal Counsel opinion prohibiting the indictment of a sitting president. Most interesting, however, are the actions neither demanded by Justice Department regulations and policy nor prohibited by the same. Here, Mueller’s perception of duty—which I see as his sense of both the tasks he needed to perform to complete his job ethically and the things he could not do because they would unethically push him beyond his core mission—illuminates his choices.

With only one exception, when the Office of Special Counsel’s spokesman Peter Carr disputed the accuracy of a Buzzfeed report, Mueller avoided commenting publicly on issues related to the special counsel’s investigation (outside of public court documents), regardless of what the president and others in the outside world were saying about him, his team and their collective work. The regulations do not prohibit the special counsel from making public statements. But Mueller chose to keep his head down and do his work.

Yet Mueller did not remain entirely silent. Regarding the report itself, the special counsel’s office could have produced a sparse text, merely listing prosecution and declination decisions with a sentence or two each for the purpose of, as the regulations require, “explaining the prosecution or declination decisions.” As Gen. Michael Hayden and I wrote last month, Mueller’s lengthy report went beyond that absolute minimum—and he wrote in the text of the report how duty drove this choice. He self-consciously wanted to preserve evidence for future prosecutors (should they choose to charge the president with crimes after he leaves office) and for Congress (should it choose to pursue the president’s impeachment). Even though he drew the line short of opining about the president’s actions, he found a way to fulfill a greater duty to the country while not violating his more direct duty as special counsel.

Another area not governed tightly by rules is whether to seek to testify before Congress. The special counsel law does not explicitly prohibit doing so, yet nothing in the statute suggests it. His requirements ended with the delivery of the confidential report to the attorney general. As for whether or how to speak publicly about his work, Mueller had a choice to make. Should he offer to go “behind the report,” to tell Congress more than the printed word conveyed?

Without getting inside Mueller’s mind or heart, it is impossible to know how he made his choice. But my experience with him and his actions to date in this investigation suggest that his sense of duty again pushed him to a strict constructionist view of his mandate. Seeking to testify, or even planting the seed for a request to testify, would have been inconsistent with his pattern of narrowly following his legal and policy guidance as special counsel.

But, as just described, he had already elected to write a report that went beyond the bare minimum. So why not lean forward here, too, and give a wink or a nod to testifying?

I suspect that here, as with the choice to write a detailed report, Mueller may have in mind a sense of greater duty to the country: accepting legitimate legislative branch oversight of the executive branch, which can come in the form of a subpoena. Mueller may prefer not to testify, but he would probably not refuse to show up if Congress demanded his presence. “There has been discussion about an appearance before Congress,” he acknowledged at his press conference before adding, “Any testimony from this office would not go beyond our report …. I would not provide information beyond that which is already public in any appearance before Congress.” He didn’t say that he would refuse to provide information to the elected representatives of the American people—just that, in doing so, he’d stay within the four corners of the report itself.

Although Robert Mueller is not a political actor, he’s been around the game long enough to understand Washington better than most, to anticipate others’ moves and to prepare for contingencies. Imagine if he had appeared eager to testify, or if he had simply left it as an open question. For the first time in more than two years, he would have opened himself up to understandable claims of being political, by seeking to do something outside his core duty, and to a barrage of hypercharged presidential tweets. At a minimum, any apparent desire to appear before Congress would risk shrinking the American people’s healthy confidence in his work.

The situation would be quite different if he were compelled to testify—even if only to read aloud, in heavily watched televised hearings, the many damning pieces of evidence and disturbing conclusions in the text of the report. Mueller would be seen as a reluctant witness, having made clear he’d rather remain in private life than spend another minute in the spotlight.

What better way would there be to fulfill a wider sense of duty than to see to it that American voters and their representatives hear the report’s words about what the president has done without pushing to do so?

More Articles

-

Justice Department Unseals Superseding Indictment in Maduro Case

The four-count indictment includes charges of cocaine trafficking and illegal weapons possession. -

The Law of Deposing Nicolás Maduro

Recent U.S. actions in Venezuela underscore the president’s broad authority to use military force. But threats of a “second wave” may still run up against its limits. -

Lawfare Daily: The Trials of the Trump Administration, Jan. 5

Listen to the Jan. 5 livestream as a podcast.

-(1).jpg?sfvrsn=739a73d4_5)