Roger Stone’s ‘Time in the Barrel’: Campaign Dirty Tricks, Political Sabotage and the Law

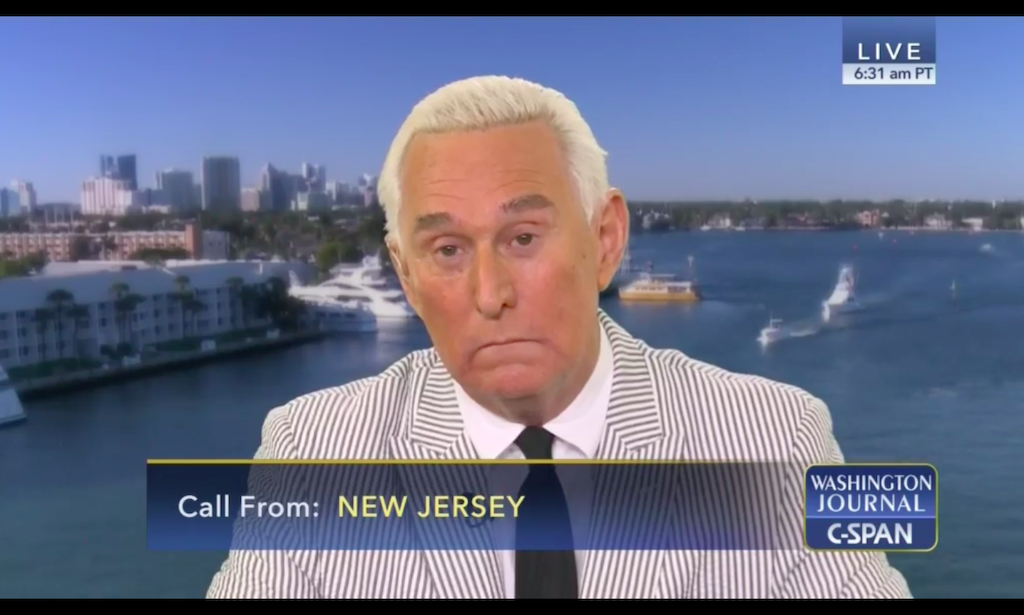

Roger Stone is pleased to be known as a campaign “dirty trickster.” A former Trump campaign aide and Republican operative, he has embraced his past as practitioner of the political dark arts. “One man’s dirty tricks,” he has said, are “another man’s political, civic action.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Roger Stone is pleased to be known as a campaign “dirty trickster.” A former Trump campaign aide and Republican operative, he has embraced his past as practitioner of the political dark arts. “One man’s dirty tricks,” he has said, are “another man’s political, civic action. He has warned that “Politics ain’t bean bag, and losers don’t legislate.” Going still further, he has articulated as one of his “rules” for success that “To win you must do everything.” Yet he has also insisted that, “Everything I do, everything I’ve ever done has been legal.”

This claim is now likely to be put to the test. News reports increasingly suggest that Special Counsel Robert Mueller is circling around Roger Stone and his associates in the Russia matter and that the legality of his “dirty tricks” is very much in question.

Stone’s argument that ”it’s all just politics” is close in kind to the First Amendment protection defenses that the Trump campaign has claimed it enjoys even if, as alleged, it had contacts with Russia and WikiLeaks. Like those defenses, Stone’s claims will be evaluated in the light of the still emerging but increasingly troubling facts of the campaign and its associates’ active connivance with the Russian cyber attack on the Democratic Party and the Clinton campaign. As the Watergate prosecutions showed, dirty tricks pursued to sabotage an opposing campaign are very much a legal issue. They are not easily passed off as good old-fashioned hardball politics, the kind that “ain’t beanbag”—especially when, as in this case, the fellow tricksters are a foreign government and its agents.

Stone and one of his associates, Jerome Corsi, appear to have conducted communications with WikiLeaks and the “Guccifer 2.0” cutout, and Stone had contact with at least one Russian national offering dirt on Hillary Clinton. Most famously, Stone predicted in August of 2016 that something momentous involving Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta—his “time in the barrel”—was about to break, two months before Wikileaks distributed hacked emails of Podesta’s. Now Corsi has provided to the press what appears to be a draft plea agreement and statement of offense produced by Mueller’s office and awaiting Corsi’s signature, which provide new detail about the extent of alleged collaboration between Corsi, Stone, and Wikileaks. The statement of offense reveals an email Stone sent to Corsi in July 2016 with the request or instruction that Corsi, “Get to [Assange] [a]t Ecuadorian Embassy in London and get the pending [WikiLeaks] emails.”. Weeks later, Corsi replied that “Word is friend in embassy plans 2 more dumps. One shortly after I’m back. 2d in Oct. Impact planned to be very damaging.”

Stone disputes that these emails “prove” that he had advance notice of the “source or content” of the stolen emails published by WikiLeaks. He says that he was merely “curious” about the pending WikiLeaks disclosures. On Stone’s account, whatever he did to find about this material, such as having Corsi “get the pending emails,” is just what a dirty trickster and master of hardball politics would do if properly schooled in the rule that “to win you must do everything.” Stone’s legal defense fund is currently appealing for donations to protect Stone from Mueller’s supposed attempts to “criminalize normal political activities.”

The investigation of Stone’s activities will not, of course, be the first time that practitioners of dirty tricks encounter the legal limits of their“normal” activities. The sundry offenses that travel under the “Watergate” moniker included such tricks—and the individual most famously identified with them, Donald Segretti, served time for his leading part. Among the activities Segretti directed was the forging of communications from one Democratic presidential campaign to spread false and malicious claims about other campaigns in the party’s primary. He was indicted for violating a provision of the 1971 federal campaign finance law that required that campaign literature distributed “in connection with a candidate’s campaign” but without the candidate’s authorization carry a notice to that effect, making clear that the named candidate was “not responsible” for its content.

The violation of this transparency requirement was enough to support a prosecution, but Congress later concluded that it needed to enact a more detailed prohibition of acts of political “sabotage.” The counterfeiting of campaign literature for which Segretti went to jail was just a means to the larger end of disrupting an opposing campaign. The 1974 amendments to the Federal Election Campaign Act included a ban on "fraudulent misrepresentation of campaign authority." The statute prohibits agents of a campaign from falsely misrepresenting themselves as acting on behalf of another, “on a matter which is damaging to such other candidate or political party or employee or agent thereof.” The nub of the new offense was the use of underhanded means to undermine the opposition. This was the purpose of the Nixon campaign’s sabotage operations: “[T]o throw the Democratic party into confusion,” to “sow confusion and discontent among Mr. Nixon’s opponents.”

Today, on a very different set of facts, Stone reportedly faces investigation for his role in acts of sabotage directed to a similar purpose. The Russian government’s theft of emails belonging to the Democratic Party and senior Clinton associates, and the distribution of these materials via WikiLeaks, were intended to wreak havoc on the Democratic presidential campaign. Few would argue that the scheme was without effect.

The connection between Stone’s activities and the Trump campaign—that is, the degree to which Stone was acting for that campaign—remains to be established. There is no doubt that Stone was linked to the formal campaign apparatus, sobeginning with the formal advisory role that Stone played in 2015 until he quit—or was fired depending on whom one chooses to believe. He remained in contact with the candidate and active in support of the Trump campaign. It seems far-fetched to believe, based on what is known to date, that Stone was off on some purely personal “dirty tricks” operation involving the Russians and WikiLeaks.

Any hope Stone may have of staying within the realm of dirty-but-legal trickery runs up against a particularly serious problem: the company that he and his associates kept. Should it turn out that they were encouraging and supporting a foreign government and its agents in any phase of the plan to acquire and disseminate stolen emails, they run headlong into the law barring foreign nationals from providing “anything of value” to an American political candidate. The rules prohibit a U.S. citizen from providing "substantial assistance" to foreign nationals violating this law. As Robert Mueller’s indictment of Russian parties for conspiracy to defraud the United States shows, Americans can also face liability under the same legal theory: conspiring to defraud the United States by failing to report these activities and thereby impeding the Federal Election Commission from discharging its law enforcement function.

Stone, an admirer of Richard Nixon who has the former president’s image tattooed on his back, would like to have Nixonian “dirty tricks” accepted as good, old-fashioned political "hardball." Not for the squeamish, perhaps, but not illegal. Along with Donald Trump, Paul Manafort, Don Jr. and possibly others in the Trump campaign, Roger Stone may have failed to realize the danger of playing these tricks in partnership with a foreign government.