The Russian Invasion of Ukraine Is Boosting the Potential for U.S. Influence Abroad

Editor’s Note: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was a shock to the international system, but it is not clear which powers will dominate the postinvasion world order. Collin Meisel, Caleb Petry, and Jonathan D. Moyer of the University of Denver and Mat Burrows of the Stimson Center examine a range of scenarios to see if and under what conditions U.S. influence might grow or shrink. They find that, across the scenarios, the U.S.-India alliance is one important factor and that it is vital for the United States to maintain its open economy.

Daniel Byman

***

More than a year after Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the world is in the midst of what German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has described as a Zeitenwende, or turning point for history. What can we say about where the world is headed?

The future could take many different paths. In a recent report with the Henry L. Stimson Center’s Strategic Foresight Hub, we explored several of the most likely paths in what is, to our knowledge, the first long-term, global, quantitative forecast of bilateral and networked geopolitical influence capacity across alternative scenarios. This analysis demonstrates that the United States can capitalize on its rivals’ errors to improve its international standing with the right foreign policy. Across all scenarios, U.S. influence depends heavily on maintaining its open economy, including providing market access to developing countries. The forecasts also contain insights about rising powers. In particular, India looks set to become a more important economic and political player in the coming decades, with the potential to offset China’s increasingly dominant influence in much of Asia and elsewhere.

Measuring and Projecting Influence Capacity

We conducted our study using the freely available International Futures (IFs) tool, an integrated assessment model created by our colleague Barry Hughes to conduct long-term forecasting and scenario analysis. IFs—which forecasts more than 500 deeply interconnected variables for 188 countries through the year 2100—allows users to model myriad alternative futures, asking “what if” and examining the cumulative and sometimes counteracting effects of various combinations of “what if” assumptions.

Geopolitical influence capacity, or the ability of one country to influence another, is the product of bandwidth—or the size of economic, political, and security-related interactions between countries—and dependence—or the asymmetries in bilateral country relationships across those dimensions. For example, influence capacity can grow both due to increasing trade between countries as well as due to increasing importance of trade for a given country, as operationalized by bilateral trade as a percentage of a country’s total trade and as a percentage of their gross domestic product. Other factors include alliances, trade agreements, shared membership in international organizations, diplomatic exchange, aid, and arms transfers. We combine these factors into a metric for states’ influence capacity, which can be assessed for each bilateral relationship or as a cumulative influence score for each country.

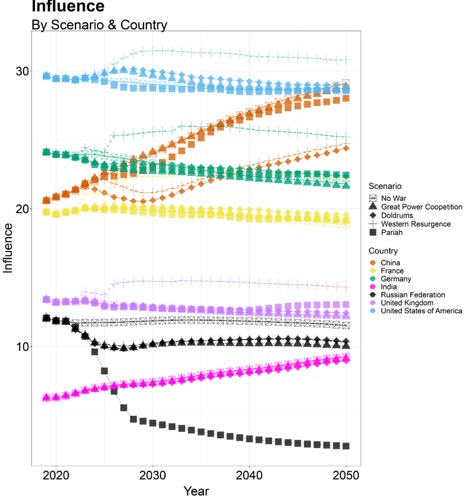

We forecast these inputs across four alternative scenarios and compared results to a baseline “No War” path in which expected shifts were projected based on a world in which Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and parallel geopolitical developments never occurred. The first of our alternative scenarios, “Great Power Coopetition,” models a continuation of current trends: a protracted war in Ukraine and a gradually rising China. The “Doldrums” considers instead the implications of a stalemate in Ukraine and a long global recession that constrains U.S. and Chinese growth. With a “Western Resurgence,” open U.S. trade policies could over the long term shift the balance of geopolitical influence to favor the United States and its partners relative to China. Finally, the “Pariah State and the Precipice of World War III” scenario considers implications of a Russian nuclear escalation in Ukraine that alienates much of the world.

Tracking Trends Across Possible Futures

Across scenarios, the war in Ukraine appears to have deferred the point at which China was projected to catch up to U.S. influence capacity, originally slated to occur around 2045, by five to 10 years. Interestingly, this contradicts our findings from forecasts generated in the early months of the coronavirus pandemic. The economic shock in the United States and the initially modest effect in China appeared to accelerate this transition, but we cautioned at the time that the projection could be affected by leaders squandering opportunities. Since then, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s pandemic mismanagement—namely the implementation of strict “zero-COVID” policies followed by a rapid and unexpected lifting of virtually all restrictions—appears to have severely hampered China’s near-term prospects. In the long run, however, our forecasts of U.S.-China influence capacity tend toward convergence, with a more open U.S. economy providing the best chance at delaying and perhaps even preventing a U.S.-China transition.

Figure 1. Global influence capacity across scenarios, where a “No War” world shows an earlier expected U.S.-China transition than all other scenarios.

Russia, meanwhile, is expected to see at least a 10 percent decrease in its global influence capacity in our present forecasts. What may ultimately prevent further losses are Russia’s deep structural connections with Central Asia. Both infrastructural connections in the form of pipelines and railways as well as the strong personal bonds among these countries’ leaders are expected to bolster Russian influence capacity in the region—an influence capacity we expect to diminish greatly if nuclear weapons are used in Ukraine.

The Middle East will likely shift toward greater independence or tip toward China. This trend is driven largely by China’s demand for oil increasing while demand in the West peaks and a Chinese diplomatic presence in the Middle East that outmatches that of the United States. Even amid a “Western Resurgence,” which includes particularly rosy assumptions about economic growth in and trade expansion by the West, the Middle East appears poised to exit the U.S. sphere of influence permanently. This may be a bitter reality to some, given the billions of dollars spent and thousands of U.S. lives lost in the region during the global “war on terror.”

Recent geopolitical developments that have already occurred since we completed the primary modeling and analysis for our report appear to be early indicators of this trend. From the Chinese brokering of warming Iranian-Saudi relations to Saudi Arabia’s forthcoming entry into the Chinese-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization, China’s star in the Middle East appears to be rising—and our forecasts show little sign of this trend slowing.

Lessons for Improving U.S. Competitiveness and Influence

Several policy implications emerge from our analysis. First, our findings highlight the importance of U.S. openness to the world in maintaining U.S. influence capacity abroad. While trade protectionism might bolster certain industries, it limits the U.S. ability to engage with and shape the world. This reality must be balanced against understandable strife among Americans who feel they have lost ground because of globalization. Balancing these challenges goes hand in hand with a need for immigration reform that respects skeptics’ concerns while acknowledging that immigrants are a key source of U.S. innovation and a crucial backstop against what would otherwise be highly unfavorable demographic trends.

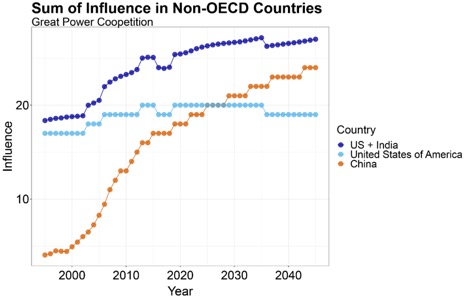

Second, U.S. policymakers must find ways to better incorporate the views of the Global South, particularly India, into a revised notion of the liberal international order. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has balked at directly criticizing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Despite disagreements like this, India would be a valuable partner. The country—the world’s most populous as of this year—is expected to see considerable growth in its geopolitical influence in the coming decades. Despite presently lagging similar-size economies, India plans to account for 10 percent of global exports by 2047. It has become an increasingly prominent regional aid donor. And it has the potential to become a key arms supplier to militaries in developing countries.

Figure 2. India as the potential “kingmaker” in the competition between the United States and China for geopolitical influence among non-Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries.

The recent strengthening of ties between the administrations of Prime Minister Modi and President Biden represents an important first step. By better appreciating and respecting India’s rise—perhaps also through calls for reforms of voting rights, agenda setting, and veto powers at the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and UN Security Council—the United States can demonstrate a good-faith attempt to share rather than dominate governance of an international system in which its own dominance is expected to diminish further and further under all but the most optimistic scenarios.

.jpeg?sfvrsn=42734a7d_5)