Safeguarding Our Homeland and Protecting Our Values

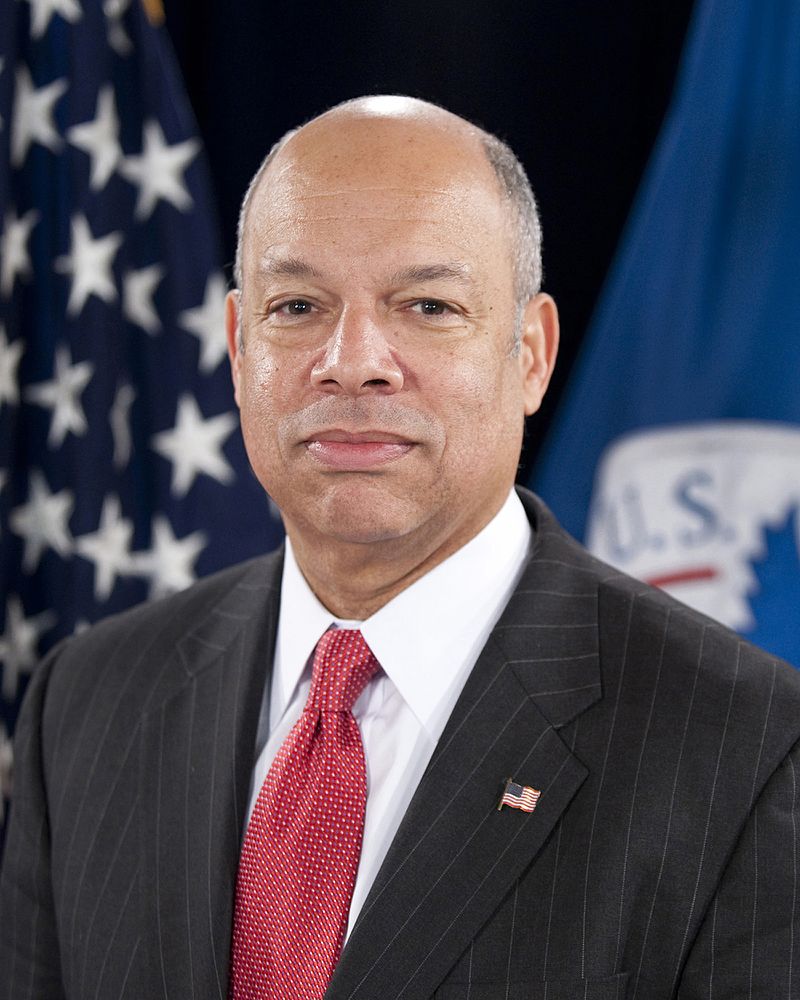

Editor's Note: This post contains the text of a speech that former Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson is delivering this hour at the Oxford Union, March 8, 2017.

***

Thank you for that introduction. And thank you for the opportunity to return to this distinguished place where Presidents, Prime Ministers, scholars and so many great people have spoken. This means a lot to me.

As I did four years ago, I hope to provide remarks relevant to the moment.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor's Note: This post contains the text of a speech that former Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson is delivering this hour at the Oxford Union, March 8, 2017.

***

Thank you for that introduction. And thank you for the opportunity to return to this distinguished place where Presidents, Prime Ministers, scholars and so many great people have spoken. This means a lot to me.

As I did four years ago, I hope to provide remarks relevant to the moment.

I spoke here four years ago, but it seems like forty. Times have changed. Then, Barack Obama had just been re-elected to another four-year term, and I was about to complete what I thought was my last position in public service.

When I spoke here last in 2012 I was the lawyer for the U.S. Department of Defense. After having given the legal sign-off for dozens of counterterrorism operations against al Qaeda and its affiliates, I decided to take on an issue that I had avoided for four years: just how would the multi-year, unconventional armed conflict we were in against an unconventional enemy, al Qaeda, come to end?

Yes, then, after more than ten years of armed conflict, during which we had found and killed bin Laden and countless other terrorists, and degraded core al Qaeda’s ability to launch another 9/11-style attack against us, I confess many of us in the U.S. government looked forward to the day when our armed drones no longer patrolled the skies over places like Yemen and Somalia, and we could bring all our troops home.

Now, four years later, it is true that the ability of core al Qaeda, based in Afghanistan/Pakistan, to attack the West has been seriously degraded, through sustained efforts by the U.S. and our partners in the international community.

But, our efforts must go on. There is a new global terrorist threat known as the Islamic State, or “ISIL,” “ISIS,” or “Daesh,” that is the successor to the al Qaeda affiliate “al Qaeda in Iraq.” ISIL is now front and center in our counterterrorism efforts.

And, this terrorist threat is fundamentally different from what it was just four years ago. Our response, too, must be different.

Four years ago the goal was to take the fight to the enemy—where they lived, where they plotted, where they trained, so they could not export another 9/11-style terrorist attack to our homelands.

Now, in addition, we must address the very real prospect of homegrown violent extremism in our midst, inspired by terrorist propaganda launched from overseas via the internet. They no longer need to physically penetrate our borders.

In the United States in particular, ISIL has in effect outsourced terrorism to those who live among us, to those they can recruit or inspire, via social media, to their cause. For ISIL, this is a low-cost, low-risk way to pursue a terrorist agenda.

This is why, in addition, to our traditional counterterrorism efforts, I spent so much time as Secretary of Homeland Security building bridges to the very communities in the United States within which ISIL seeks to recruit. In three years, I visited American Muslim communities in Boston, New York, Washington, northern Virginia, Chicago, Columbus, Ohio, Houston, Minneapolis, and Los Angeles. Last year I became the most senior member of the U.S. government to ever address the Islamic Society of North America’s annual convention in Chicago. That was controversial in some quarters, but the opportunity, as U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security, to speak to 10,000 American Muslims all at once was something that could not be passed up.

Outreach to Muslims within our own communities is not a liberal or conservative cause. It’s not political correctness. It’s common sense in the current environment. In his Senate confirmation testimony, my successor John Kelly, who now serves in Donald Trump’s Cabinet, said of his time as a commanding general in Iraq: “the way we won, certainly in my part of Iraq, was …outreach[] to people, convinced them that we were there for good, not evil, that we were there to protect them and help them … I know Secretary Johnson does this and I certainly will continue that.”

My former U.K. counterpart, now Prime Minister Theresa May, has also promoted partnerships with isolated communities in this country, to “reclaim the debate from the extremists” and “empower those who want to celebrate our values and defeat ignorance.”

It is in such an environment, in which we must detect and deter extremist threats that live among us, that great and free nations must resist the impulse to overreact, to vilify innocent people, and to compromise our values.

This is what I want to talk to you about tonight: lessons learned in safeguarding our homeland and our values at the same time.

On this topic, there is the elephant in the room—the current volatile political situation in my own country. But tonight I speak to those here from all Nations that cherish both their security and their freedom.

In early 2016 President Obama directed me and Secretary of State John Kerry to resettle 10,000 Syrian refugees into the United States, and to do it within the next nine months, by the end of Fiscal year 2016, on October 1, 2016.

This was going to be a big undertaking. We had settled only 1,600 Syrian refugees the year before. This was a six-fold increase We were going to have to up our game considerably.

I admit now that my first reaction then, viewed solely from the perspective of my homeland security chair, was one of trepidation.

We were going to have to increase to 10,000 the number of refugees we accepted from a war-torn, terror-infested country that had within its midst the Islamic State’s self-proclaimed caliphate. Viewed solely from the perspective of our own physical security, some might say we should close our borders to all refugees from that region, to buy down risk, and not increase it.

But there were other considerations.

A natural outgrowth of a country plagued with terror and violence is innocent men, women and children who are the victims of that same terror and violence, in the very same place, left with no choice but to flee their homes. Centered in Syria and Iraq, there was then and is now a worldwide refugee crisis.

And, great nations do not close their eyes and padlock their doors to a worldwide refugee crisis.

Surely, the United States could absorb just 10,000 Syrian refugees, a fraction of one percent of the total refugee population while other nations in Europe had no choice but to absorb far more.

Surely, on this small planet, where there exists enormous disparities between rich and poor, feast and famine, and security and violence, the landlord expects the most powerful of his tenants to help the weakest and most desperate.

So, we upped our game. We rededicated resources across multiple U.S. government agencies to a refugee vetting process that was already multi-layered, time-consuming, thorough, and takes one to two years to complete. We added more security checks to the vetting process. The process always deserves continued scrutiny and re-evaluation in response to an evolving global threat picture. But, today, the U.S. process for vetting refugees encompasses scrutiny by multiple departments from our homeland security, national security, law enforcement and intelligence communities.

With that, we met and exceeded President Obama’s charge.

Last fiscal year we admitted and resettled over 12,000 Syrian refugees, and 85,000 overall—an increase of 10,000 over the year before. And today thousands of men, women and children have a better, safer life as a result.

These people have real names, real faces and real stories—people like Kamal, a Syrian refugee who we resettled in Texas with his wife and children after he had been imprisoned and physically tortured by the Assad regime, including the forcible removal of one of his kidneys; people like Dima, an Iraqi refugee who happens to be my daughter’s college roommate; people like Jafar, a 9-year old Iraqi boy who I met in a refugee processing center in Turkey almost exactly a year ago. In perfect English that he learned watching TV, Jafar told me of his dream to come to the U.S. Today Jafar, his mother and two sisters live in United States, and I am convinced that in 10 years Jafar will be a student at Stanford, Princeton or maybe even here at Oxford.

In the fall of 2014 our Nation was swept with fear and anxiety about the deadly Ebola virus emanating from West Africa. A handful of cases emerged in the United States, with the prospect for more. For a while every passenger who got sick on board any airplane bound to the United States, from anyplace in the world, was breaking news on CNN and a matter that demanded my immediate, personal attention.

In this environment, many argued that the United States should suspend the issuance of all visas to citizens from Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea, the three countries from which the virus had originated.

I admit that my first reaction, solely from my homeland security perspective, was the same—to ban travel from these countries, and buy down the risk of anyone else from West Africa carrying the virus to our country.

Here again, there were other considerations.

Other nations were looking to the United States for leadership in the Ebola crisis. If the U.S. had shut our doors to all the citizens of Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea, they would have done the same. The civilized world would have isolated these three countries at a time when they needed us most.

We adopted a more considered approach. Rather than suspend visas from West Africa, we funneled all air travelers from the three affected countries to just five airports in the U.S., where they were subject to enhanced screening specifically for symptoms of the Ebola virus. After that, not one person infected with Ebola entered the U.S. unless they were coming here for treatment, with our knowledge.

Meanwhile, thousands of brave men and women from the U.S. military and the health community led an international coalition to West Africa to combat and ultimately stamp out the Ebola virus. The United States led in the response to an overseas crisis, and protected ourselves at the same time.

The lesson is this:

In national security, the first reaction is not always the best one. In a free and democratic society, national security means striking a balance between our basic physical security and the values we hold dear as a people. In national security, we are the guardians of one as much as the other.

This is true across the entire spectrum of homeland security—not just when it comes to refugee resettlement or defending against the spread of a lethal virus.

I can build you a perfectly safe city, but it will look and feel more like a prison.

I can build you a perfectly safe, risk-free commercial flight, but you’d never wanted to take it. No one would be able to conceal anything, because you would not be wearing any clothes, you would not be allowed any checked luggage or carry-on items, food, the ability to unfasten your seatbelt, leave you seat, or go to the restroom.

I can build you a perfectly cyber-secure email system, but you would be confined to a conversation with about 20 people you know and trust inside a firewall, with no access to the internet or the larger world around you.

Visit almost any facility in the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and you will see posted a simple 15-word mission statement we issued for the first time in 2016:

With honor and integrity, we will safeguard the American people, our homeland and our values.

What are those values?

In most free and open societies, they include the freedom to travel, the freedom to associate, the freedom of speech and dissent, the freedom of religion, privacy, the celebration of diversity, and adherence to law.

When I was sworn in as Secretary of Homeland Security, the judge who administered the oath to me added: “Remember, you just took an oath, not to protect and defend the homeland, but to protect and defend the Constitution.”

In this, history must be our guide.

History teaches us that in free and open societies, government overreach in the name of national security almost always leads to an equal and opposite reaction from other democratic forces—in the legislature, the courts, or, ultimately, in the court of public opinion.

Those who know history must learn from it; those who don’t know history are bound to repeat it. For those of us who know our history, the latter is painful to watch.

Six days ago at the Oxford Union you were supposed to hear from Khizr Khan, but his trip here was postponed. Last summer Mr. Khan captured our country’s attention with his compelling defense of the patriotism of Muslim Americans, demonstrated by the heroism of his own son, U.S. Army Captain Humayun Khan, who died for his country in Iraq.

Sixty eight years ago, during the McCarthy era in the United States, my own grandfather, sociologist Charles S. Johnson, was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee to deny he was a member of the Communist Party and defend the patriotism of African Americans. To do so, he too was obliged to invoke the African American’s willingness to fight for the country:

In one sense it is liking asking if Tennesseans, or Presbyterians, or foreign-born citizens, or American women, or persons with freckles, are loyal. They are all basically Americans … If we examine the familiar indices or national loyalty, the efforts and ambitions of American Negroes have at times been embarrassingly excessive. In time of war they have pleaded for combat service, for the supreme hazards of military service … Wanting the elimination of inequalities and racial discrimination is not wanting to subvert the Government.

Despite Dr. Johnson’s words, paranoia about the Communist influence persisted in the U.S. into the 1960s, as Martin Luther King—a man for whom there is now a national holiday in the U.S.—was the subject of FBI surveillance for suspected connections to Communists.

Those who know history must learn from it; those who don’t know history are bound to repeat it.

At this elite University and this historic Union of future world leaders, I urge all of you to learn from the mistakes history. Do not repeat them.

A nationalistic, we’re-in-it-for-ourselves fervor rarely leads to good things. The world is too small a place.

Those in public office, or who otherwise command a microphone, must not simply curse the darkness; we must light a candle.

Real leaders lead, not by pandering to fear, suspicion and prejudice, but by showing a better, more enlightened way. The former is expedient, the latter is hard.

There is a famous quote attributed to a number of people, including Mahatma Gandhi: "there go my people, I must follow them for I am their leader." This was self-effacing sarcasm from one of the most transformational figures of the 20th century, but it is sadly reflective of too many politicians today who deal in stereotypes, pander to fear, or irresponsibly peddle “alternate facts.”

Follow the fine example of so many of those who have come before me to speak at this Union. Nothing less than peace and freedom depends on it. Thank you.