Second-Guessing Congress on Military Commissions

Friday’s D.C. Circuit decision on military commissions, Al Bahlul v. United States, rests on a narrow, grudging reading of Congress’s war powers.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Friday’s D.C. Circuit decision on military commissions, Al Bahlul v. United States, rests on a narrow, grudging reading of Congress’s war powers.

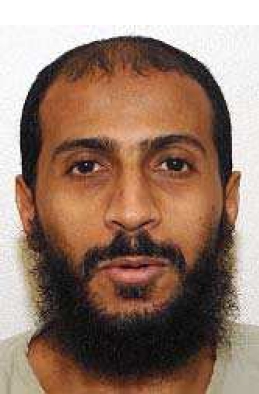

Judge Judith Rogers, joined by Judge David Tatel (who filed a concurrence), vacated the military commission conviction of Ali Hamza Al Bahlul, a former bin Laden aide, for inchoate conspiracy. The full D.C. Circuit had acknowledged in its en banc opinion last year that Al Bahlul’s acts were “directly related” to the 9/11 attacks. Nevertheless, the panel on remand held Friday that the conspiracy conviction violated Article III of the Constitution, because military commission judges lack Article III’s protections of judicial independence, such as lifetime tenure. As Judge Karen Henderson wrote in her insightful dissent, judges Rogers and Tatel misread the Supreme Court’s precedents on non-Article III courts, which have taken a more pragmatic approach and largely deferred to Congress’s Article I powers. (Full disclosure: along with Jim Schoettler, I wrote an amicus brief for scholars and former JAGs and national security officials asking the panel to uphold Al Bahlul’s conviction.)

Definitely Not Déjà Vu: From 2014’s En Banc to the Panel’s Decision

Casual readers not steeped in military commission law may regard Friday’s holding as incongruous, since the full D.C. Circuit last years upheld Al Bahlul’s conviction against a challenge based on the Ex Post Facto Clause (in an opinion by Judge Henderson joined by Judge Tatel, among others, with Judge Rogers dissenting). Al Bahlul had argued to the en banc court that the Military Commission Act (MCA) of 2006 first gave commissions jurisdiction over inchoate conspiracy at the time of its passage, yet Al Bahlul’s acts occurred no later than 2001. Consequently, Al Bahlul argued, his conviction violated the Ex Post Facto Clause’s requirement that a defendant have adequate notice that his conduct was illegal at the time he committed the acts at issue. While the MCA also gave commissions power to try violations of the law of war, Al Bahlul argued on appeal that the law of war as of 2001 did not include inchoate conspiracy.

Last year’s en banc decision applied a highly deferential “plain error” standard to the conviction, since Al Bahlul had forfeited his right to anything but minimalist review of the Ex Post Facto issue by not asserting it at trial. In finding that it was not “obvious” that pre-MCA commissions could not try defendants on inchoate conspiracy charges, the en banc court cited several factors, including both the U.S. history of inchoate conspiracy prosecutions in military tribunals and the nexus between Al Bahlul’s acts and the 9/11 attacks, which entailed the murder of U.S. civilians--a clear war crime. Because trying the inchoate conspiracy charges was not a “plain error” that fatally undermined the fairness of the proceedings, the en banc court rejected the Ex Post Facto challenge, although the logic of the decision suggested that a less deferential de novo standard could yield a different result. The en banc court then remanded to a panel to adjudicate whether Al Bahlul’s conviction violated Article III.

Al Bahlul and Waiver of Constitutional Arguments

In Friday’s decision, Judge Rogers got right one preliminary question: whether Al Bahlul forfeited the right to attack his conviction on Article III grounds. If Al Bahlul had forfeited, the panel would have analyzed the Article III issue under a deferential plain error standard, as the en banc court had analyzed the Ex Post Facto Clause argument. But Judge Rogers found that Al Bahlul had not forfeited the right to make the Article III argument, because that argument was structural in nature. Judge Henderson disagreed in her dissent, arguing for application of plain error. The Supreme Court’s precedents on this issue favor Judge Rogers.

In 2003’s Nguyen v. United States, the Court held that a defendant’s failure to lodge a timely objection did not preclude review of the defendant’s argument that the presence of a non-Article III judge on a panel reviewing his conviction violated Article III. Justice John Paul Stevens, writing for the Court, drew support from the court’s opinion in 1962’s Glidden Co. v. Zdanok. In Glidden, the court was not deterred by an untimely Article III objection. It addressed the merits of the defendant’s claim that Article III barred trials in the District of Columbia presided over by retired judges of the Court of Claims and the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals. After exhaustive analysis, the Court concluded that the courts in question were actually Article III courts with the judicial protections befitting that label. This example suggests that functionalists should grapple with structural questions de novo, instead of relying on the plain error standard.

Article III and Military Tribunals: The Duel Between Functional and Protective Approaches

That finding tees up the merits of the Article III issue in Al Bahlul. Military tribunals--both commissions and courts-martial--have been a battleground in a decades-old contest on the interaction of Articles I and III of the Constitution. The functional view asks (1) whether a non-Article III tribunal facilitates Congress’s goals in the exercise of its Article I powers, and, (2) whether a limiting principle curbs the risk to judicial independence. Cases like Commodity Futures Trading Commission v. Schor and Thomas v. Union Carbide support this functional view. The Court has pushed back only when, as in 2011’s Stern v. Marshall, permitting a non-Article III tribunal to adjudicate a dispute would open the door to wholesale adjudication of disputes such as tort or contract matters traditionally triable in state courts.

Judge Henderson’s dissent and my forthcoming UC Davis paper reflect this functional approach. In Schor, the Court upheld a statute that permitted an agency to resolve counterclaims regarding a broker regulated by the agency, although the counterclaims would ordinarily be heard in a state court or an Article III tribunal. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, writing for the Court, noted that allowing the agency to hear such claims permitted the efficient adjudication of disputes regarding brokers. Moreover, Justice O’Connor found, the matters covered by the statute were specialized in nature and limited in scope. Those constraints provided a “limiting principle” that curbed congressional evisceration of judicial independence.

The functional approach contrasts with what I’ve called the protective approach, championed by Justices Hugo Black and John Brennan and most recently defended by Steve Vladeck. (See Steve’s Georgetown piece here and Geoff Corn and Chris Jenks’ response here.) The protective approach rightly regards Article III adjudication as among the most compelling calling cards of American constitutionalism. It is therefore suspicious of any encroachment on Article III protections. Acolytes of the protective approach read Congress’s Article I prerogatives narrowly and discount the efficiency concerns championed by functionalists. In Al Bahlul, D.C. Circuit Judges Rogers and Tatel embrace the protective approach.

Commissions, International Law, and Inchoate Conspiracy

The difficulty that drove the majority’s opinion on remand in Al Bahlul concerned the authority of military commissions to try a defendant on charges of inchoate conspiracy to commit a war crime. The Supreme Court said in 1942’s Ex Parte Quirin (the Nazi saboteurs case) that a military commission could try defendants for violations of the law of war, which the Court depicted as predominantly, if not exclusively, international in nature. The Court cited the Constitution’s Define and Punish Clause, which authorizes Congress to define and punish offenses against the law of nations, and also cited Congress’s array of war powers in Article I, section 8 of the Constitution. In a crucial passage, the Court described commissions as an “important incident” of waging war, since commissions deterred an adversary’s wrongful conduct during an armed conflict. According to the Quirin Court, military commissions had fulfilled this role since before the Constitution’s enactment, for example, in General Washington’s convening of a military commission to try British major John Andre for espionage. At least in cases addressing accepted violations of the law of war, Quirin found that military commissions are not “courts” within the meaning of Article III, and therefore do not require Article III protections.

However, (and here’s the rub per Friday’s Al Bahlul panel) international law does not define inchoate conspiracy as a war crime. Inchoate conspiracy under U.S. law entails merely an agreement between defendants and a minor overt act furthering the conspiracy. In contrast, international law only authorizes trying conspiracy as a form of liability for a completed act. That is, a defendant who plots to murder civilians can be charged with the murder of civilians, as long as civilians have in fact been killed. The theory is that a plotter of a murder contributes to the result just as surely as the person who does the killing. International law since Nuremberg has not recognized inchoate conspiracy, in part because of concerns that charges based on mere agreement will be too vague and punish guilty thoughts, rather than deeds. For Judges Rogers and Tatel, the lack of clear support in Quirin for military commission trials of inchoate conspiracy doomed Al Bahlul’s conviction.

Al Bahlul’s Conspiracy: Completed in Fact and Function But Not Charged as Such

Al Bahlul’s conspiracy involved administering the “bayat” or Al Qaeda oath of allegiance to two key 9/11 figures: Mohamed Atta, the leader of the hijackers during the U.S. phase of the operation, and Ziad Jarrah, one of the pilots. According to FBI agent Ali Soufan, who interrogated Al Bahlul (without “enhanced” methods), Al Bahlul also had acted as a “minder” for Atta and Jarrah at Osama Bin Laden’s compound, preventing them from going off course. Al Bahlul proudly acknowledged in evidence admitted at trial that his conduct played at least an “indirect” role in the 9/11 attacks.

As Judge Henderson noted, this evidence would support a claim that Al Bahlul participated in a conspiracy or Joint Criminal Enterprise (JCE) that resulted in the mass murder of U.S. civilians on September 11. JCE requires merely that a defendant be a “cog in the wheel” that results in a completed war crime. The members of the military commission that convicted Al Bahlul expressly found that he committed the acts alleged. Unfortunately, for reasons that remain unclear, the prosecution did not charge Al Bahlul with JCE or conspiracy as a form of liability for the completed act of murder of civilians, but only with material support (which the en banc D.C. Circuit held last year was not a crime triable in military commissions) and inchoate conspiracy. The members of the jury were instructed that they need not consider whether Al Bahlul’s acts had contributed to a completed war crime, although the only element missing from the instructions was a complete act, and Al Bahlul never disputed that the 9/11 attacks had occurred.

Necessary and Proper Defining and Punishing: Back to the Framers

A functional theory would argue that Congress’s power to define and punish violations of the law of nations extends to acts like Al Bahlul’s that violated international law. Judge Henderson, like Judge Janice Rogers Brown in her insightful concurrence in last year’s en banc decision, explained that the Framers drafted the Define and Punish Clause to enable Congress to navigate through the often confusing waters of international law. A measure of deference to Congress serves the Framers’ design.

Moreover, the Necessary and Proper Clause, as the Supreme Court ruled recently in U.S. v. Comstock and Chief Justice Marshall wrote in McCulloch v. Maryland, allows Congress to enact provisions that are “conducive” to exercise of its express Article I powers. Congress could readily have found that even plotting to commit an acknowledged war crime such as the murder of civilians posed an unacceptable risk that the defendant would violate international law. Preventing a completed act by intervening at just the right point between the plot and its execution strains government resources and imperils potential victims. Adding a level of deterrence beyond ordinary civilian courts is conducive to Congress’s aims. Moreover, requiring an Article III tribunal for a foreign national with no ties to the U.S. who plotted abroad and was captured overseas would require officials to transport the plotter to the U.S. for trial--a consequence that seems “impracticable and anomalous,” per Justice Kennedy’s concurrence in U.S. v. Verdugo-Urquidez (holding that the Fourth Amendment did not apply to overseas searches of individuals with no U.S. ties).

Furthermore, a limiting principle would check the encroachment of military tribunals on Article III trials: a commission could only try a defendant on charges that were reasonably related to international law. Under the Military Commission Act, an Article III appellate court reviews legal questions de novo, easily meeting the standard Justice O’Connor set out in Schor.

In Friday’s D.C. Circuit decision, Judge Rogers rejected this perspective, relying on a cramped reading of the Necessary and Proper Clause. Judge Rogers cited Toth v. Quarles, where Justice Black wrote for the Court in holding that a court-martial lacks jurisdiction over a discharged member of the armed forces. Black argued in Toth that a contrary result would have authorized court-martial jurisdiction over millions of former members of the armed forces who had made the transition to civilian life. No such concerns are present in Al Bahlul, which does not raise the specter of the military trial of large numbers of U.S. civilians. When dealing with foreign nationals captured overseas plotting violations of the law of war, the Necessary and Proper Clause entails greater deference to Congress.

Moreover, Judge Rogers mischaracterized the Supreme Court’s threshold for appellate review of factual determinations by non-Article III tribunals. Judge Rogers asserted that the Supreme Court has demanded more probing review of the facts than the Military Commissions Act provides. However, this contention reflects an unduly formalistic reading of the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Crowell v. Benson. In Crowell, the Court recognized that, to facilitate Congress’s scheme for efficient adjudication of specialized disputes, the agency’s adjudication of facts had to be “final.” [p. 46] The Crowell Court held that, as long as those findings were supported by some evidence, the Constitution was satisfied. While the “based upon evidence” standard in Crowell is superficially less deferential than the MCA, which permits review only of legal questions, in practice this is a distinction without a difference. A court reviewing a military commission conviction wholly unsupported by evidence would classify that conviction as an arbitrary decision raising issues of law. In other words, while Judge Rogers read the Necessary and Proper Clause grudgingly, she exaggerated the Supreme Court’s test for appellate review of facts.

It is also worth noting that the Supreme Court has never struck down a statute making inchoate conspiracy triable by military commission. In Hamdan, a plurality of Justices (not including Justice Kennedy) found that inchoate conspiracy was not an international law war crime. However, the plurality’s principal concern was with allocation of powers between Congress and the President. Justice Stevens’ opinion stressed that his central problem was with President Bush’s unilateral order granting commissions authority to try conspiracy charges. Justice Stevens expressly reserved the question of Congress’s power under the Define and Punish Clause. Justice Kennedy, in his concurrence in Hamdan, stressed that Congress was better situated than the courts to assess the United States’ obligations under international law.

Conclusion

In sum, judges Rogers and Tatel are right to address the Article III question de novo. After that initial correct move, however, they construe Congress’s Article I authority over military commissions far too narrowly, and fail to accord Congress the deference that the Define and Punish Clause and Necessary and Proper Clause contemplate. Judge Henderson’s comprehensive and thoughtful opinion may have been the dissent in this round. Don’t be surprised, however, if Judge Henderson’s opinion provides a template for the last word in this long-running case.