Selling Spirals: Avoiding an AI Flash Crash

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

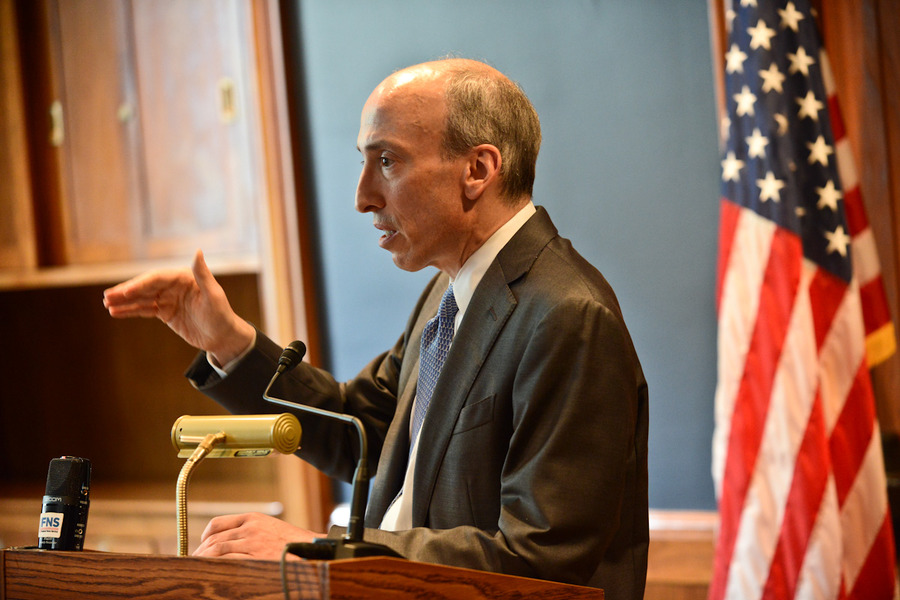

A year ago Gary Gensler, the chair of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), made a dire prediction: Artificial intelligence (AI) would cause a financial crisis if regulators did not act soon. His warning has largely gone unheeded. Insufficient action—and widespread inaction—in response to Gensler’s warning suggests that his concerns have not been addressed. In fact, his fatal predictions have become even more probable.

With a new administration looming and AI still booming, now is the time to reexamine Gensler’s prediction, analyze proposed solutions, and map out specific steps forward.

The Prediction

Gensler anticipates that, when people reflect on a hypothetical, near-future economic crisis—perhaps one occurring as soon as the late 2020s—they “will say, ‘Aha! There was either one data aggregator or one model ... we’ve relied on.’” Put differently, broad use of a few models trained to respond in similar manners to similar situations will cause a slight downturn in the market to become a rapid collapse.

This prediction seems like a good bet—partially because it’s arguably already nearly happened. In 2010, a flash crash occurred in the market due to a number of high-frequency trading algorithms engaging in a series of rapid trades. Perhaps most troubling, this quick dive took place on an otherwise normal trading day. A few algorithms in use simply “misread” the market. The unwarranted sell-off initiated by those mistaken models then caused other programs to respond in kind. The $1 trillion lost in that half hour period was eventually made up thanks to human intervention.

But this was not a fringe case. A similar algorithmic hiccup also took place in 2016. In that case, analysts attributed an overnight 6 percent drop in the British pound to algorithmic trading. This incident confirmed the susceptibility of algorithms to “high-speed selling spirals.”

One such spiral took place even more recently. Earlier this year, a typo in Lyft’s earnings report (anticipating that a profitability metric would surge by 500 basis points rather than the actual 50) resulted in trading algorithms rushing to buy the stock. In just a few hours of after-hours trading, Lyft was up 60 percent. Only when humans realized the mistake did the stock come back to reality.

Since then the use of trading algorithms has only increased—as has deference to their alleged sophistication. Algorithmic trading tools complete as much as 75 percent of all trades in some markets. The biggest trading companies are racing to adopt similar tools for their clients—opting to rely on algorithms rather than rely on human wisdom. This is unsurprising given that the first firm to detect even a slight move in the market may make substantial gains for their clients. The sum of these trends amounts to a “horizontal issue,” which Gensler defines as “many institutions ... relying on the same underlying base model or underlying data aggregator.”

Mitigating the risks of such algorithms has not gotten any easier. The 2016 drop in the pound was partially explained by the fact that algorithms act on a litany of information sources, including what’s trending on social media platforms. Contemporary AI models are trained using even more data and have access to even more information.

What’s more, despite some progress in explainability and interpretability, AI decision-making remains a black box. If AI trades included a rationale, then perhaps they could be trained to reliably avoid participating in any selling spirals. This latter factor reiterates the relevance of Gensler’s concerns, despite those who would argue otherwise, suggesting that algorithmic trading is actually an improvement on irrational human traders. The thinking goes: Aren’t humans susceptible to “animalistic spirits” that can drive markets downward or upward for no good reason? While that’s true, the distinguishing factor about algorithmic trading is its speed. For a sense of just how much faster algorithmic trading can steer the market, consider that “since 2017 and the introduction of LLMs, the movement of US equity prices 15 seconds after the release of the Fed minutes seem to be more consistently in the direction of the longer-lasting movement seen after 15 minutes, in contrast to the apparently uncorrelated movements in the pre-LLM period.” Briefly, whatever “spirits” may move AI manifest faster and may persist longer than those animating human traders.

Select Proposed Remedies

A range of options exist to limit the likelihood of Gensler’s worst-case scenario. The obvious one—banning the use of such tools—is off the table given the industry-wide reliance on algorithmic trading. Other interventions, however, are more feasible and may be quite effective.

One step toward a market resilient to selling spirals may come from the SEC’s proposed “predictive data” rule. The proposed rule’s lengthy title, “Conflicts of Interest Associated with the Use of Predictive Data Analytics by Broker-Dealers and Investment Advisers,” obfuscates a straightforward attempt by the agency to ensure that firms do not use algorithmic tools in a manner that places their own interests ahead of investors’ interests. As summarized by the SEC, “the proposed rules generally would require a firm to evaluate and determine whether its use of certain technologies in investor interactions involves a conflict of interest that results in the firm’s interests being placed ahead of investors’ interests. Firms would be required to eliminate, or neutralize the effect of, any such conflicts, but firms would be permitted to employ tools that they believe would address these risks and that are specific to the particular technology they use, consistent with the proposal.” If finalized, the rule may reduce excessive reliance on algorithmic tools, especially if firms are unable to meaningfully govern how and why those tools make certain trades.

The likelihood of the proposed rule moving forward, however, appears to be decreasing. Since the SEC shared the proposal in July 2023, it has received substantive comments from influential stakeholders—many of them in opposition. Several stakeholders have conveyed that the regulation suffers from significant ambiguity. The definition of the technology covered by rule, for instance, was characterized by more than a dozen members of Congress as “so vague and expansive that it would include tens of thousands of technologies that have been in common use for decades, including spreadsheets[.]” Others have been less blunt in their assessment, while pointing out room for improvement. James Tierney, Kyle Langvardt, and Ben Edwards, for example, noted that existing law, if stretched, may cover much of what the SEC appears to be aiming to achieve with this regulation, thereby rendering the rule unnecessary. But given the rule is on the backburner, it does not appear that even this partial solution will address Gensler’s concerns in the near future.

A more targeted and, perhaps, effective response would be to change how trading is actually done. Albert “Pete” Kyle, after studying the issue of market crashes as part of the Brady Commission, has called for stock exchanges that change the actual placement and timing of orders. His crash-resilient market would require traders to buy a specific number of shares and identify the maximum speed at which those shares may be bought. This approach would spread the purchase of a share over the course of a day: “[T]raders would just have to send one order, making time and price and quantity essentially continuous.” In turn, you’d acquire a fraction of a share over the entire day until your order is eventually completed. This would mark an improvement on the current approach, which lends itself to selling spirals by allowing algorithms to “chop an order into very small pieces and submit an order every couple of minutes, automatically adjusting the price as necessary to make sure an order goes through.” Kyle’s proposal would prevent such aggressive trading and, by extension, decrease the odds of stocks experiencing changes in price caused by small, yet numerous trades.

More complex proposals aim to identify unsettling market trends and nip them in the bud before a crash manifests. Andrew Lo, a professor at MIT Sloan, has mapped out a means for regulators to monitor the behavior of large institutions without requiring those institutions to tip their hands to competitors. His complex proposal involves those institutions “hand-encrypting” their activities—sharing their plans with regulators without identifying themselves and enabling the regulator (via algorithmic analysis of all such submissions) to get a sense for how the market may move. Akin to the creation of a National Weather Service to gather information on the climate and predict future trends, Lo anticipates that this system would increase the odds of regulators spotting warning signs earlier and, as a result, avert worst-case scenarios.

A litany of other proposals abound. None has gained tremendous regulatory momentum.

Some people, such as Tyler Cowen of the Mercatus Center, argue that the solution to Gensler’s concerns is more AI—not less. Cowen maintains that increased use of AI by traders may actually diminish the likelihood of a crash. He acknowledges that overreliance on just a few models could lead to selling spirals but posits that the number of models will only increase over time. As the number of models increases, he expects that the diversity of trading approaches will as well. Firms reliant on more innovative, bespoke models will likely do better for their clients, which is the name of the game. Realization of Cowen’s goals, then, requires its own policy response: ensuring competition in the AI development space. Such a policy response has yet to be implemented.

Indeed, bipartisan consensus around any substantive AI regulation has not emerged on the Hill. Prevention of selling spirals induced by algorithmic trading may be a starting point. Both Democrats and Republicans have expressed support for transparency measures related to developing and deploying AI. A new report may provide reason to apply that focus to the context of algorithmic trading.

The Next Steps

The October 2024 Global Financial Stability Report completed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) leaves little doubt that AI broadly and generative AI specifically are contributing to increased volatility in capital markets. Based on a jump in patent filings related to algorithmic trading, the IMF expects continued integration of algorithms into trading activity. This outcome would align with a survey of market participants who generally agreed that “high-frequency, AI-driven trading” will increasingly be the norm rather than the exception.

Whether this surge in innovation results in the sort of positive outcomes envisioned by Cowen is far from certain. The IMF warns that these tools are only becoming more sophisticated, which may hinder efforts to understand if “more” algorithmic trading is actually better or merely stacking the deck for a calamitous collapse. Citing higher variability in AI-driven exchange-traded funds, the IMF seems to suspect the latter is the more likely outcome. That skepticism is further warranted because difficult-to-monitor nonbank financial intermediaries may be the first and most aggressive adopters of these tools.

This report could and should restart conversations on the Hill about how to prevent Gensler’s frightening forecast. There is no shortage of policy solutions to diminish such an outcome. Transparency measures around which institutions are relying on which models may be a good place to start. The IMF, for one, has called for financial sector regulators to demand that nonbank financial intermediaries disclose AI-relevant information. This information, combined with similar disclosures from financial institutions, would facilitate the detection of the problematic interdependencies behind flash crashes.

Gensler may turn out to be the SEC chair who cried AI. The resiliency and stability of the financial system, though, warrants taking him seriously and ensuring worst-case scenarios remain hypothetical.

.png?sfvrsn=94f97f2c_3)