Senate Confirmation Is a Recipe for Politicizing Military Personnel Policy

Sen. Tuberville’s hold on general officer nominees is another example of a system struggling with basic functions.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: Sen. Tuberville’s hold on U.S. military promotions has resulted in extensive delays in general officer confirmations and is creating serious strain on the military leadership. The U.S. Military Academy’s Jake Barnes, Zachary Griffiths, Scott Limbocker, and Lee Robinson examine congressional holds in the context of the overall U.S. military promotion process. They find long delays are common and argue that the process today is needlessly politicized.

Daniel Byman

***

In mid-February 2023, Sen. Tommy Tuberville (R-Ala.) began issuing holds for general officer confirmations over disagreements with a Department of Defense policy providing travel and transportation allowances for abortion care. As a result of these holds, the U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps simultaneously lacked confirmed leaders for the first time in history earlier this year. Now, more than 300 executive military promotions are on hold.

These holds impede the Senate confirmation process by requiring the Senate to confirm these officers through regular voting procedures rather than the unanimous consent votes that typically move these nominations forward. According to a recent Congressional Research Service report, normal voting procedures would now take more than 689 hours of Senate floor time to work through the backlog of nominations as of Aug. 22.

Scholars, pundits, and administration officials have all decried these holds as the politicization of the military. Yet, for all the attention that Tuberville’s actions are garnering, the Senate’s rules have routinely delayed confirmations over the past 40 years. Focusing solely on the holds of one senator misses the larger problem: that the U.S. government subjects the appointment and nomination of general officers to the political whims of elected officials rather than merit-based promotion principles in the first place. It is time to revisit this practice.

A History of Military Appointments

Political influence on military appointments has existed since the first days of the United States. President Washington delegated his appointment power to Secretary of War Henry Knox, who sought to balance the geographic makeup of military officers, requiring home-state senators to vouch for the character of their appointees. However, party politics quickly influenced the nomination and oversight process. With the support of Federalists in Congress, the Adams administration used the appointment and oversight process to pack the officer corps with Federalists, which the Republican Jefferson administration reversed.

As a result, selection for officer positions was based much more on political loyalties than on merit, leading to the dismissal of experienced officers and delays in the nomination process. Asked by Secretary of War James McHenry to select highly qualified candidates for nomination to military appointments in the Adams administration, former President Washington expressed his frustration over the influence of partisan politics on the fate of his nominees. In a letter to Secretary McHenry in 1799, Washington bemoaned that his recommendation of military appointments that minimized “influence of favor or prejudice” could be sidelined by any member of Congress with a “prejudice to endulge [sic].” The Adams administration experienced delays in confirmation of the handful of general officers to lead the U.S. military’s 30,000 troops in 1799. The Framers surely did not anticipate that this force would grow to the 653 general officers that lead today’s active-duty force of nearly 1.3 million service members, but the text of the Constitution indicates they gave Congress latitude to determine how general officers reach their position.

Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution states that the president “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other Public Ministers and Counsels, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all Other Officers of the United States, whose appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by law.” Does this provision in the Constitution imply that the process of Senate confirmation should apply to the nomination and appointment of all general officers? Or does the nomination and appointment of general officers fall under the Article II, Section 2, power of Congress to “vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone … or in the Heads of Departments”? This discretion for Congress to define “inferior Officers” set in motion a century-long process of reforming government positions to be based on merit rather than patronage.

As party politics developed further throughout the 19th century, patronage was a central factor in military appointments, just as it was for federal civilian offices. Concerned in part about the lack of expertise in patronage appointments for some federal offices, Congress exercised its power to delegate appointment of “inferior Officers” and authorized the executive branch to move jobs in the government toward a merit-based civil service, beginning in earnest with the Pendleton Civil Service Act of 1883. Subsequent reforms, like the Hatch Act of 1939, expanded civil service protections to create a professional, merit-based system of federal employees that limited the influence of partisan politics on selection and promotion to promote expertise and efficiency.

More recently, the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 created the Senior Executive Service (SES) to establish a class of merit-based, potentially long service career executives to strengthen expertise within the federal bureaucracies. The Defense Department contains more than 1,000 of these individuals, who make up around an eighth of the SES in the federal government. Within the Defense Department hierarchy, SES members and general officers occupy offices with similar responsibilities in the Pentagon, but with starkly different confirmation processes. For example, the Defense Department’s tiering structure to compare civilian and military positions notes that an Executive Level III SES member is equivalent to a one-star general officer. While equivalent in status, a career SES member is filled through a merit staffing process insulated from partisan influence, while the general officer faces the inherently political Senate confirmation process.

Military appointments lagged behind other federal employees in stepping away from patronage appointments. In 1947, the passage of the Officer Personnel Act set the foundation for the current merit-based promotion systems in the armed services. Since the subsequent passage of the Defense Officer Personnel Management Act of 1980, one- and two-star general officers have been centrally selected in a merit-based system in each of the services, with three- and four-star general officers nominated by service secretaries.

The nomination and appointment process for general officers has three significant steps: selection of nominees by the Defense Department, nomination by the president, and action by the Senate. Within the Defense Department, military services filter potential candidates for promotion through their General and Flag Officer Management Offices, and then send slates of candidates to the Joint Staff and the Office of the Secretary of Defense for selection. Once selected, senior leaders in the Defense Department send slates to the president. Typically, presidential approval is swift. The president then sends the nomination slates to the Senate. In some cases, such as in the selection of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, the president may interview candidates to hand-select his statutory military adviser. While disagreements may occur between the services and the Defense Department and president over nominations, they are rare and usually involve unique circumstances, such as Secretary Robert Gates’s nomination of Gen. Norton Schwartz to correct what he saw as fundamental flaws in the Air Force’s priorities.

Once general officer nominations arrive at the Senate, they are referred to the Senate Armed Services Committee, which has jurisdiction over the Defense Department and military services. Upon referral to the committee, the chair generally exercises discretion over whether or how to move a nomination through the committee. If the committee approves, the nomination is then referred to the full Senate, which again may or may not put the nomination on the agenda. An affirmative vote of the full Senate is required for confirmation. The Senate most often confirms through voice votes but also holds recorded votes on a handful of nominees per year.

The vast majority of nominations receive Senate action, but no Senate rule requires action. In fact, senators possess two tools to prevent or delay nomination: the filibuster and the hold. One or more senators may threaten “extended debate” or the filibuster. Similarly, the Senate custom of “holds” can delay consideration of an action, such as a nomination. The Senate’s rules of unanimous consent for nominations allows a large number of nominees to move through confirmation relatively quickly, but as Tuberville’s actions demonstrate, the process can be derailed by a single senator withholding consent. The Senate does not distinguish between types of holds, but scholars have. Informational holds request that a senator be notified before action, while “Mae West holds” aim to foster negotiations through having a bill sponsor visit the holding senator’s office to discuss a policy. Retaliatory holds are designed for political payback, while rolling (or rotating) holds occur when two or more senators coordinate in their holds. Tuberville’s hold is classified as a “choke hold” that has an explicit filibuster threat.

Holds and other tactics of the Senate have been used on military personnel matters to shape policy. For example, Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.) placed a hold on Lt. Gen. Susan Helms’s nomination because the general decided to overturn a sexual assault conviction. Fighting in the same policy space, Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) placed a hold on the undersecretary of the Navy. In these cases, active-duty military and civilian appointments were leveraged in a policy dispute. Ultimately, the senators were able to get their reform in the 2013 National Defense Authorization Act, underscoring the effectiveness of this strategy that Tuberville seized on this year.

While holds on whole slates of confirmations is new, the actions taken here are well within the rights of each elected official. Hand wringing about this interjection of politics into the military misses the point that in these instances the senators were acting well within their rights as elected officials under current rules. Hoping that norms hold is not sufficient to ensure merit personnel practices or prevent politicization.

The Limits of Congressional Oversight, in Data

Tuberville’s choke holds are a dramatic example, but a close analysis of general officer nominations demonstrates that this type of politicization of U.S. military policy is just one of several issues with the current Senate confirmation process. To examine the extent and consequences of partisan influence on general officer nominations, we created a new data set of all general officers nominated by the president for confirmation by the Senate over a 40-year period. This data set includes all presidential nominations for flag and general officers posted to Congress.gov between Jan. 22, 1981, and Sept. 21, 2022, and the open nominations of the 118th Congress from Jan. 3 to July 11, 2023. The unit of analysis is the nomination, which includes information on the number of nominees, the rank of the nominees on the slate, the Senate number, the date the president sent the nominees to the Senate, and the date of final adjudication.

The data reveal two trends about presidential nominations. First, Tuberville’s actions, while leaving open jobs at the very top of the Defense Department for the first time and approaching the historical high end of delays, is not a radical outlier relative to other congresses. Second, the Senate’s confirmation activity is closely associated with a regular pattern of delays driven by advice and consent procedures for general officers that are of Congress’s own choosing.

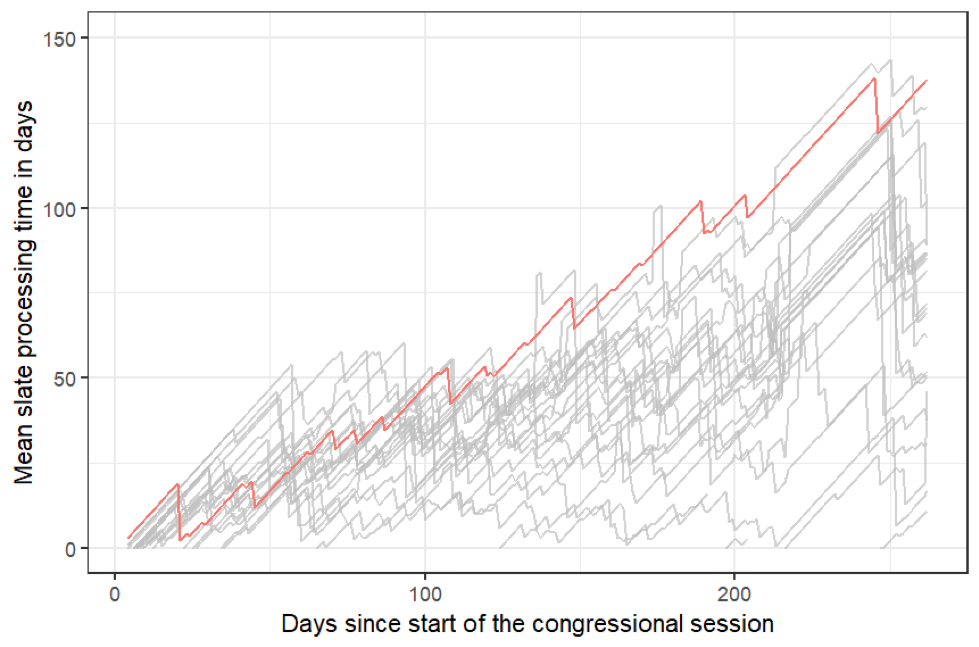

The delays due to Tuberville’s holds are high in both quantity and duration, and have recently surpassed all other delays in the first 263 days of a Senate (through Sept. 21, 2023). This is evident in Figure 1, where the red line depicts the mean slate processing time for all active slates in the current Congress. By Sept. 21, the end of our period of study, Tuberville was withholding his consent for 144 slates of candidates for nomination, effectively putting on hold the promotion or appointment of more than 300 general officers. While Figure 1 compares Tuberville’s holds against all previous nominations since 1981, he has had holds on nominations only since mid-February. Despite his headline-making holds, there are more mundane factors that have led to the same result of delayed nominations for general officers.

Figure 1. Average time between nomination and congressional vote, by congressional session.

Some of these delays result from the Senate calendar. For decades, Congress has scheduled lengthy recesses of one week or longer to align with regular periods throughout the year. The longest recesses occur around August and the end of a session (sometime between October and December), but shorter recesses regularly occur around President’s Day, Easter, Memorial Day, July 4th, Thanksgiving, and the month immediately before the biennial election day in early November. When looking at all congressional sessions between 1981 and 2022, the Senate acted on 1,600 (or 24 percent) of the 6,957 nomination packets within seven business days of the August and end-of-session recesses and took an average of 53.5 days to process a nomination.

This pattern has two potential implications. First, the Senate calendar, rather than national security, serves as the primary forcing function for processing general officer nominations. Second, because the calendar guides confirmation activity, the 53-day average processing time does not necessarily increase civilian oversight of general officer promotions. Rather, it simply reflects the pro forma nature of the confirmation process. Whether it is a hold or simply not prioritizing the confirmation on the Senate calendar, delays like this, absent sound policy concerns surrounding the nominee, are not good for national security.

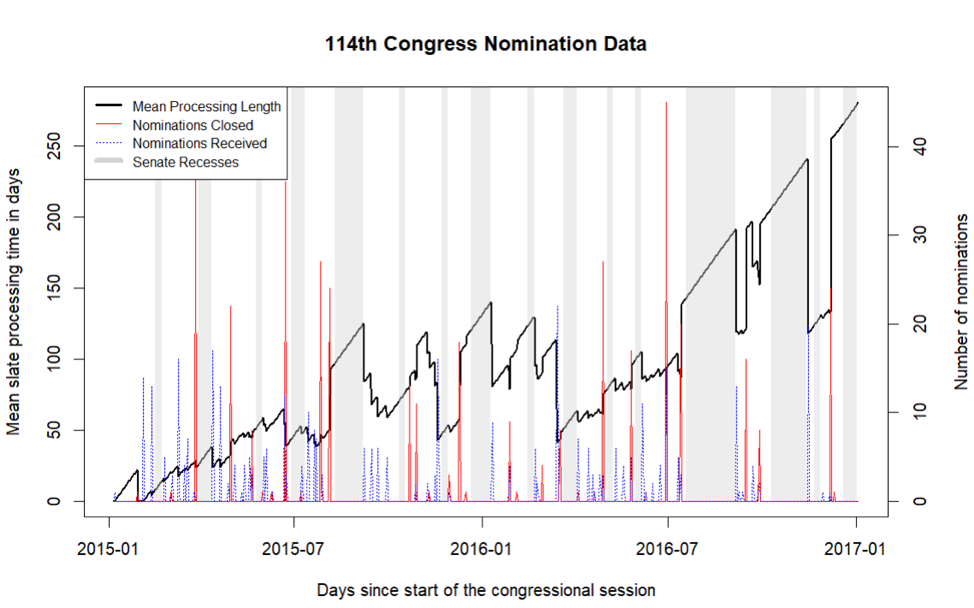

The 114th Congress (2015-2016) is a typical example of the calendar-based pattern of general officer confirmations, with an average nomination length of 53.7 days and 92 (or 22 percent) of its 419 general officer nominations occurring immediately before the August or end-of-session recesses. Figure 2 maps both confirmation activity and Senate recesses across the length of the term. The plot reveals multiple single-day spikes in confirmation productivity, which generally occur close to long recesses (as indicated by the red lines) and are separated by long periods of inactivity. Some of the observed decreases in the mean are an artifact of new slates being introduced (blue lines), which drops the overall mean despite no one being confirmed. Also, the mean can jump if newer nominees are confirmed while older nominations remain in the queue. Of the 419 general officer nominations in the 114th Congress, the Senate took action on 232 (55 percent) within seven business days of all the long recesses outlined above. This further supports the pro forma nature of calendar-based confirmations. Additionally, on the days that included confirmation activity, the confirmation votes were the last official order of business before adjournment, reflecting their low priority relative to other Senate matters.

Figure 2. General officer confirmation delays in the 114th Congress.

Even though the Senate expedites four-star nominations, the previously identified pattern of calendar-based action persists among nominations for the highest ranked members of the military, with 89 (54.6 percent) one-star and 18 (54.5 percent) four-star nominations occurring within seven days of a long recess.

This historical comparison of general officer confirmations shows that the institutional arrangement of the Senate produces irregular intervals at which general officer positions are filled. This is a systemic problem that strains the military’s ability to make decisions and provide for the national defense. Empty positions leave the U.S. military without key decision-makers. Acting officials can serve only as caretakers and do not want to paint the eventual nominee into a corner with their decisions. Also, it forces the Defense Department to consider if the acting person even has the legal authority to make decisions in some cases, which takes time away from thinking about how to defend the nation. In a world of great power competition, having the top military officials in the country stagnated between jobs, and those top jobs at best being run by temporary custodians, puts U.S. security at risk as global incidents occur.

Reform or Continuity?

Despite the potential harms of the current system, there are compelling arguments to leave it in place. After all, the system is a constitutional requirement and is intended as a form of civilian oversight of the military and a check on executive overreach. But these justifications for maintaining current practices are outdated and unwarranted. The U.S. government and military would be better off changing the way at least some, if not all, general officers are nominated and removing politics from the promotion process of these merit employees.

The Constitutional Requirement

The Constitution requires the Senate to confirm many different types of employees. As a recent CRS report notes, though, the military personnel in question fall under “all Other Officers of the United States,” which is hardly a well-defined group. Moreover, at the time the Constitution was drafted, the country had a very limited number of offices to which people could be appointed and none of the merit protections that the current civil service enjoys. The Pendleton Act, Hatch Act, and Civil Service Reform Act have all moved the United States toward a merit-based civil service.

That we have not extended merit protections to general officers is peculiar. Most SES are hired through merit practices within the Defense Department and are not subject to a Senate vote. That general officers have equals in the organizational chart with different career pathways, one political and one apolitical, is a contradiction.

Another argument could be that the president needs to be able to relieve a general officer should that individual not enact the policies of elected officials. That is a fair position, but the at-will removal by the president describes a political appointee, not a modern civil servant with various forms of protection from removal. Even if at-will removal was deemed essential for general officers, this position conflates removal for past actions with promotions for future work. The order for promotion of every officer notes that they are being selected for their potential, not their past deeds. For-cause removal presupposes a past bad act. Merit principles should capture the latter if they are meaningfully being enforced by the organization.

Congressional Oversight of the U.S. Military

Congress conducts oversight of the executive branch. Voting to confirm top officials in government enables Congress to have a say in the people who will shape policy implementation. Yet the modern size of government makes it so that evaluating every nomination on the merits is an impossible proposition. It would require a diligent scrub of hundreds of profiles every year to make any sort of judgment on the merits just for general officers. At the same time, making confirmation votes a pro forma exercise is a poor use of the Senate’s time and moves away from merit principles.

Worse, if judgments for promotion are not made on the merits, then the Senate serves only to interject politics in the personnel decisions of the military. To be clear, this is distinct from setting policy for the Defense Department, which the Senate must do as part of the civilian control of the military. Politicizing personnel has its own deleterious consequences that deviate from meaningful oversight. Now any aspiring officer seeking to rise through the ranks to the top of the organization could be subject to the whims of the political moment. This is currently happening: An interest group, the American Accountability Foundation, is looking for every statement made by a pending appointee caught in Tuberville’s holds for comments on the topic of diversity, equity, and inclusion, so that the blocked slate can be labeled as “woke.”

Wedding the promotions of career personnel to the political proclivities of elected officials is the exact sort of politicization of federal agencies that years of civil service reform have sought to strip away from how the United States governs. That the current system interjects this into the military is a (correctable) mistake that harms civil-military relations.

Congressional Check on Executive Overreach

The tension between Congress and the president was an intentional design by the Founders, and, while it makes for messy processes, it has positioned the United States to be a global military leader. But this tension is inherently political. By having both branches be a part of the confirmation process, it is inviting the politicization of personnel. In most cases, it is just the Senate rules and calendar-delaying votes. But Tuberville’s political choke holds are exactly what the Senate rules are designed to enable. That we subject all general officer confirmations to those rules impinges on merit-based practices. In putting the Senate against the executive on confirmation votes, general officers are thrust into these political disputes regardless of what the military may desire, to the detriment of civil-military relations.

Removing the advise and consent procedure for general officer nominations does not remove Congress’s civilian control of the military. Congress can use its oversight authority to hold hearings and control policy through authorizations and appropriations. The president also can still use due process procedures to remove general officers, as with other merit-based employees in the case of misbehavior.

Conclusion

The recent focus on Tuberville’s holds misses the broader problem. Requiring the Senate to vote on confirmations invites the idiosyncrasies of Senate rules and the preferences of each senator into shaping the careers of top professionals in the military. Many other jobs—even some equivalent jobs in the organizational hierarchy of the Defense Department, such as the career members of the Senior Executive Service—do not involve Senate approval. To avoid the politicization of the military going forward, these professional officers need to have career pathways based on merit rather than politics.

The views in the article are those of the authors and not the U.S. Military Academy, U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.