Senate Judiciary Committee Examines the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act and Coronavirus-Related Suits Against China

The Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing on “the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, Coronavirus, and Addressing China’s Culpability”—and the proceedings demonstrated that this corner of foreign relations law has become a political lightning rod.

Since March, more than 14 suits have been filed against a variety of Chinese governmental entities, alleging China’s culpability in causing the coronavirus pandemic. One of the greatest obstacles to these suits is the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 (FSIA), which presumptively shields all foreign states and their agencies and instrumentalities from the jurisdiction of U.S. courts.

For the most part, legal experts have been skeptical that the plaintiffs in these suits will be able to convince courts that their cases fit into the act’s existing exceptions to immunity. But there is another potential path: an amendment to the act that would create a new, China- and coronavirus-specific exception to immunity that would allow these suits to proceed. That idea has provoked a variety of positive and negative reactions, and it raises complicated questions about international law, diplomacy and U.S. foreign relations.

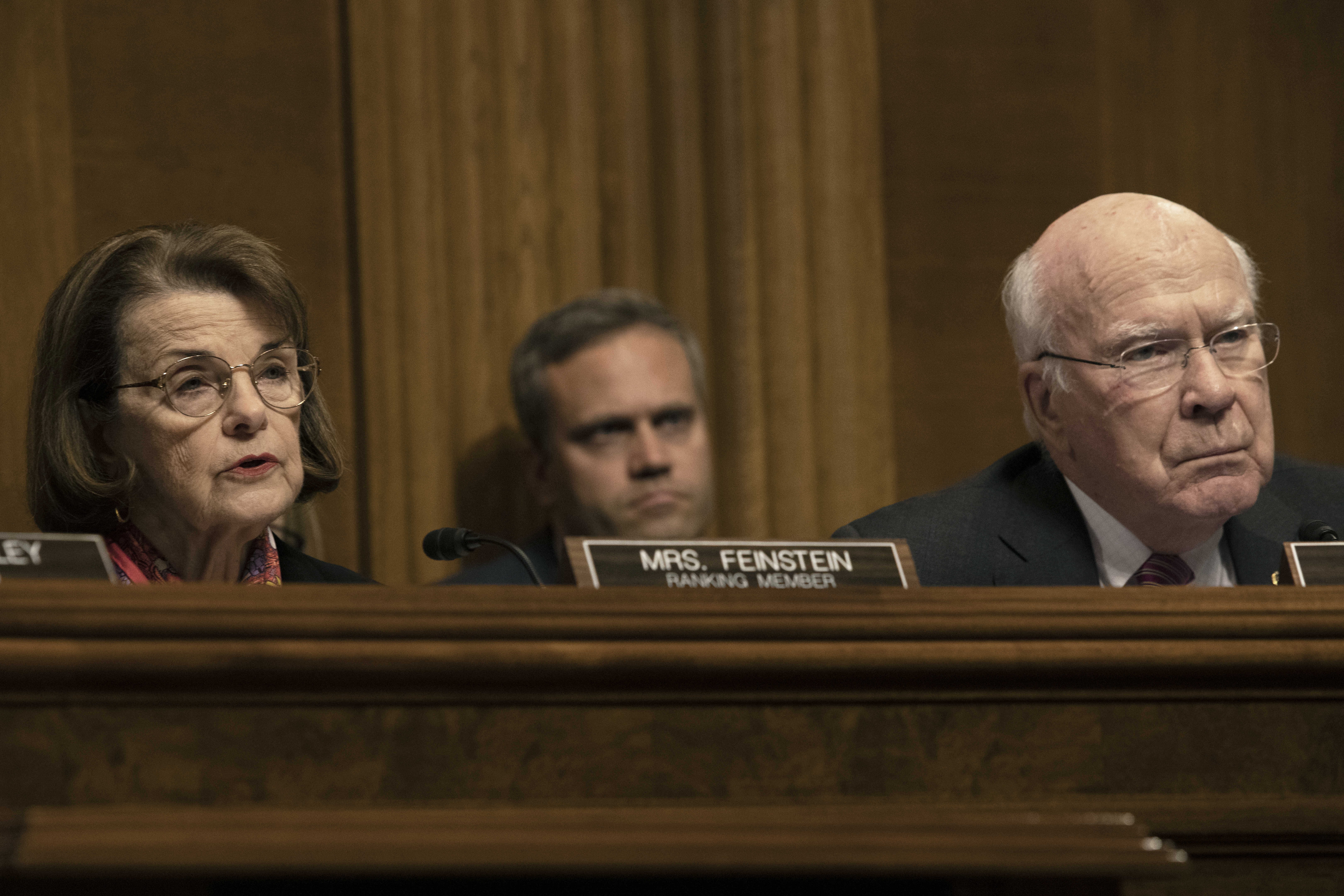

The Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing on June 23 on “the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, Coronavirus, and Addressing China’s Culpability.” Sen. Lindsey Graham presided as chairman, and Sen. Dianne Feinstein was present as the ranking Democrat. They welcomed three witnesses: Lynn Fitch, attorney general of Mississippi, who has brought a suit on behalf of her state against China; Russell A. Miller from Washington and Lee University School of Law, an expert on public international law and transboundary harm; and Chimène Keitner from UC Hastings Law School, an expert on international law and civil litigation.

Opening Remarks

Graham kicked things off by acknowledging that amending the FSIA was not an issue he took lightly. One of the primary risks of amending the act, he observed, was the inevitable boomerang effect: “[W]hatever we do to them, they can do to us.” He nevertheless argued that it may be time to take the “unprecedented step” of allowing suits against China because China had failed to act responsibly, and not for the first time. “This is the third pandemic to come out of China,” he stated. “At what point in time do we need to put on the table new ideas to stop a recurring event?”

Graham declared that he could not think “of a more compelling idea than to allow individual Americans or groups of Americans to bring lawsuits against a culprit, [the] Chinese government, for the damage done to their family, to our economy, and to the psyche of the nation.” He was therefore contemplating having a markup on legislation that would amend the FSIA “regarding Chinese culpability involving the coronavirus.”

Feinstein came at the issue from a very different perspective. She agreed with Graham that China’s behavior during this crisis needed to be examined. But she also thought that “our own government’s conduct, what the Trump administration did or failed to do, should also be examined.” She argued that it would be impossible to account for China’s role without also looking at decisions the president “made before the pandemic that made the United States more vulnerable.”

Fitch testified first, stressing the enormous consequences of the pandemic for Mississippi and the United States as a whole. She argued that “tremendous loss ... could have been avoided had China acted as a more responsible global citizen.” She thought China should be held accountable, noting that “[i]f an American company had engaged in actions like [China’s], attorneys general across the country would be lining up at the courthouse doors to file suit” and attorneys general would be filing consumer protection suits. Mississippi, she argued, was simply following the same logic: letting China know that “we will not allow them to act with impunity” and “will use whatever tools we have at our disposal to seek justice.”

Miller was next. Basing his remarks primarily on the “canonical” Trail Smelter arbitration, in which Canada was found internationally liable for cross-border pollution damage, Miller argued in support of holding Beijing accountable for its “international law responsibility for the substantial transboundary harm its acts and omissions may have caused.” He suggested that one way to fairly and equitably determine the Chinese government’s responsibility was through “an independent international institution before which all interested parties could participate to establish the facts and influence the interpretation and application of the law.” Such an arbitration, he thought, “would advance the health and human rights interests of the Chinese people” by signaling “the good faith need for a confident resumption of the world trade regime” and by bolstering China’s reputation as “a responsible, reputable, and respected global power.”

Keitner (who has written on this subject on Lawfare) concluded the round of witness opening statements. She offered three points. First, she argued that “the United States has more to lose than any other country by removing the shield of foreign sovereign immunity” because of its “unparalleled global footprint.” Second, she believed that “private litigation will not bring China to the negotiating table and it will not produce answers or compensation for U.S. victims.” She added that trying to use China’s sovereign immunity as leverage was “like using a stick of dynamite to try to put out a forest fire.” Third, she urged the United States to “focus on our domestic response and restoring our global leadership,” including through a call “for an international independent investigation and for a bipartisan panel ... akin to the 9/11 Commission.”

Senators’ Questions

Opening remarks concluded, Graham launched into questioning. He focused his inquiries on whether stripping China’s immunity was necessary, and whether anything else had worked in changing China’s behavior. Fitch argued that the FSIA already had a “workable” exception for purposes of Mississippi’s suit, but that the proposed legislation would nonetheless “be extremely helpful” by adding tools to the toolbox. Miller was more sanguine about the efficacy of the existing exceptions, which suggested to him the value of the legislation. Finally, Keitner advised that other instruments—like sanctions—would be “much less likely to boomerang back.”

Feinstein started her questioning by pointing out that the witnesses had not been sworn in. “My bad,” responded Graham and, oath duly-if-belatedly administered, the hearing continued. Feinstein focused her questions on raising the possibility that these suits are a politically motivated tool to shift blame away from the Trump administration onto China—a possibility that Fitch (and Graham) flatly denied. Feinstein also asked Keitner about the viability of these suits, which Keitner thought was low.

Sens. Chuck Grassley and Chris Coons were the next two questioners, and their approaches proved a study in contrasts. Grassley raised concerns about piercing the immunity that protects China’s assets, argued that Congress “shouldn’t be swayed by foreign threats or speculative retaliation,” and claimed that it would only be fair for Americans to have “full legal recourse against China” given China’s own, “aggressive[] use [of] domestic and international legal system[s] as part of what it calls three warfares.” By contrast, Coons used his time to argue that Congress should assess “a disorganized and chaotic federal response,” that other countries might try to hold the United States liable for its response to the pandemic, and that the Trump administration’s decision to withdraw from the World Health Organization would likely lead only to greater Chinese influence in that organization.

Sen. John Cornyn then sparred with Keitner about a variety of issues, including the congressional authority to strip China’s sovereign immunity; China’s share of blame for the pandemic; and whether the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (JASTA), which stripped immunity in certain international terrorism cases, was a successful precedent. It emerged that they agreed the pandemic had originated from China and that Congress had the authority to strip China’s sovereign immunity if it wanted. Their major debate, however, was over whether that would be a good idea.

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse took his turn next. He explained that he was interested in discussing an entirely different topic—“some of the other stuff that’s going on at the Department of Justice,” which the senator repeatedly described as “weird”—and he spent his full time (and an extra minute) sharing his views on those events.

Sen. Mike Lee subsequently returned to the topic of the hearing and walked, step by step, through his understanding of China’s failures and omissions. Sen. Richard Blumenthal parried with a list of mistakes made by the Trump administration; he also congratulated Fitch on her “uphill battle to vindicate the rights and losses of the people of Mississippi.” Blumenthal also inquired whether Mississippi was relying on reports that the coronavirus might have been produced in a laboratory in Wuhan. When Fitch said “no,” Blumenthal explained he thought that was “a good thing because I can tell you from my review of the intelligence ... there is no evidence to support that kind of claim so far as I know.” Blumenthal concluded his period of questioning by reaffirming his support for JASTA.

Sen. Ted Cruz returned to the charge against China. He wanted to know what the witnesses thought was the best way to achieve “a clear, objective, trustworthy account of China’s culpability,” and the best way to guarantee that China was “held accountable for the deaths and devastation that resulted from [its] misconduct.” Graham jumped in to amend the question and add a third issue: the best way to deter future bad behavior. Keitner responded that domestic litigation held out only “a false hope and a false conception” of what could be accomplished; she urged an international investigation, combined with sanctions, intelligence sharing and sending public health experts to China. Miller agreed that “an international independent commission” was the way to go but argued that a “robust inquiry by domestic institutions” would be useful as well. Fitch argued that “legal action and discovery” was “[t]he strongest way that we can move forward.”

Sen. Mazie Hirono tried to shift the focus to the Trump administration, repeatedly asking the panelists about the adequacy of Trump’s response to the pandemic.

Sen. Josh Hawley counterattacked, saying that it appeared that his Democratic colleagues saw “the United States and China [as] roughly equivalent bad actors when it comes to the Coronavirus,” which he thought sounded “a lot like the Chinese Communist Party propaganda that we’ve had jammed down our throats for the last several months.” Hawley then told Fitch that he was proud of her suit as well as the fact that his home state of Missouri had also sued Beijing. He asked her whether she would welcome an additional clarification from Congress that the FSIA applies to “this set of circumstances.” Fitch said “absolutely,” arguing that “[a]ny additional exceptions would provide broader avenues for states and individuals to seek justice.” Hawley clarified that his bill would also give courts the authority to “freeze Chinese assets in this country ... in order to award damages.” Fitch said, “That would be extremely helpful.” Miller added that, to whatever extent these suits might “actually generate some measure of justice for victims,” they would also “supplement[] international negotiations and international law measures” by applying additional pressure.

Sen. Cory Booker addressed his questions exclusively to Keitner. He argued that “China is a bad actor that is threatening in so many ways our economy” and now “our health.” He asked Keitner for suggestions on what tools Congress can “use to push China and frankly other countries to impose strong and serious bans on wildlife markets” to avoid future pandemics. Keitner suggested that a treaty or some other sort of international cooperation would be most effective, and if China refused to participate, it could be “shame[d].” Booker finished by asserting that these civil suits could be dangerous, because they could “dredge up a lot of complications and ... mistakes that were made by the Trump Administration.”

Sen. Joni Ernst defended the Trump administration’s response before pivoting back to China’s culpability. “China has absolutely no respect for the law,” she asserted, noting that the country had threatened to retaliate against the United States for any suits brought against it. Ernst asked Fitch how Congress could help alleviate any concerns about Chinese retaliation. Fitch had no direct response; instead, she indicated that “we’re prepared, and if we continue to hold them accountable, if we go for monetary damages and civil penalties, and we begin the deterrent process, they will stop.” Graham jibed that he didn’t “like China’s chances in Mississippi given what I’ve heard from the Attorney General.”

Sen. Marsha Blackburn also lambasted China before asking Fitch about whether she thought other states would join in the lawsuit. Fitch responded that she anticipated more attorneys general joining, noting that “[w]e have already sent a letter of 21 Attorneys General requesting continued action legislation to give us more tools to proceed.” She added that “we’re going to use every tool at our disposal, and the more that [Congress is] able to provide through additional exceptions and legislation is extremely critical.”

Key Takeaways

Three major takeaways from the hearing are immediately apparent.

First, there seems to be a unanimous recognition on both sides of the political aisle that China bears a considerable portion of the blame for the pandemic and that the United States should endeavor to hold it accountable in some way.

Second, the senators split sharply along partisan lines over what that accountability should look like. Not all of the Republican senators endorsed the idea of stripping China’s sovereign immunity, but the majority indicated at least an openness to the idea, and several have proposed legislation to that effect. By contrast, most of the Democratic senators seemed to be opposed to amending the FSIA, instead suggesting that a combination of soft power and sanctions might provide the best path forward.

Third, it is clear that the issue of amending the FSIA will remain mired in domestic politics. On the whole, the Democratic senators seemed at least as interested in attacking the Trump administration’s response to the pandemic as they did in analyzing how to hold China accountable. Likewise, the Republican senators were eager to defend the administration’s response, and they repeatedly sought to stress the extent to which the pandemic’s origin and scope could be laid at China’s doorstep. Of course, none of that should be surprising less than six months out from the 2020 election, but it does emphasize the degree to which this issue may continue transforming an esoteric foreign relations law issue into a political lightning rod.

Graham has indicated that the Republican senators who advocate stripping China’s immunity are busily working to reconcile their competing bills. Given the tone of the June 23 hearing, it seems unlikely that this will be the last we hear of such legislation.