An Off-the-Shelf Guide to Extended Continental Shelves and the Arctic

Alarmed rhetoric about great power competition over the Arctic has been based partly on common errors about extended continental shelf claims. Accurate descriptions of these claims are necessary to understand what is—and what isn’t—at stake.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On March 31, the Russian Federation partially revised its submission for an “extended” continental shelf in the Arctic, further overlapping Russia’s claims with Canada’s and Denmark’s. Despite political and academic experts calling for a calm response, CBC, Canada’s largest broadcaster, framed the submission in dire terms. Canadian academic Robert Huebert described Russia’s claim as worrying and related to Russian troop movements in Ukraine.

The CBC article is just the latest in a string of articles to air one of two common but dangerous errors about extended continental shelf claims. Extended continental shelves matter because they are the last major resource trove with unsettled state jurisdiction. At stake are exclusive rights not just to plentiful oil and gas reserves but also to various other mineral deposits, including cobalt, nickel, manganese and other critical metals for modern economies. Continental shelves matter particularly in the Arctic, where dashed lines and overlapping claims are often used to fuel narratives that the Arctic is a powder keg as Russia, the U.S. and China compete for resources or predominance.

The most fundamental error is to mischaracterize what an extended shelf claim entails. Authors make this error when they write that a continental shelf claim will extend an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) beyond 200 nautical miles. They likewise err when they say that a coastal state has sovereignty over the continental shelf.

Examples of this error abound in articles on the Arctic. Joseph Micallef, writing for Military.com, claimed that “[t]his EEZ can be extended up to 350 nautical miles,” while in War on the Rocks, Elizabeth Buchanan and Bec Strating wrote that “[Russia, Denmark and Canada] will likely deliberate between themselves any extended exclusive economic zone claims.” Describing the race for the Arctic, Kristina Spohr wrote, “Yet a nation can lobby for [an EEZ] of up to 350 nautical miles from shore, or even more—if it can prove the existence of an underwater formation that is an extension of its dry land mass,” and Sergei Medvedev asserted that “Russia’s claims to an extended EEZ overlap with claims made by Denmark, Canada, and the United States [sic][.]” (Medvedev’s comment also erroneously asserts that the U.S. has made a claim and ignores that the U.S. and Russia have already delimited any possible overlapping shelf claims.) The “extended waters” mistake is not limited to the Arctic context. In 2020, the Economist claimed, “The effect of [the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) recommendation] is to extend Argentina’s territorial waters beyond the normal 200 nautical miles.”

The second common error misdescribes the role of the CLCS in resolving the claims. Such misconstructions attribute to the CLCS far more power than it possesses. While this error is less common, CBC wrote that “if [the U.N.] approved [Russia’s 2021 claim], Russia would have exclusive rights to resources in the seabed and below it.” The Barents Observer, a key outlet for Arctic watchers, claimed that “[i]f approved [by the CLCS], the Russian claim will expand the country’s territory by 1.2 million square kilometers.” The Danish Defense Intelligence Service warned that an adverse CLCS ruling could drive Russia to “choose a different approach.”

In this post I offer a corrective to these errors with a special focus on the Arctic. First, I define three relevant terms. Next, I explain the true nature of extended continental shelf claims—specifically that this entails sovereign rights, but not sovereignty, over resources in the seabed and subsoil, but not the water column. I then describe the CLCS’s role, which is to delineate the outer limits of the continental shelf, not delimit competing claims. Finally, I explain that equidistance, rather than natural prolongation, will likely form the basis for a negotiated or arbitral delimitation settlement.

Terms

The legal continental shelf is not synonymous with the geological continental shelf. The legal continental shelf is the seabed and subsoil under the water column up to 200 nautical miles from shore or to the edge of the continental slope, whichever is farther (with some technical rules on maximum distance). Every coastal state, regardless of the actual presence of a geological continental shelf, is entitled to a legal continental shelf of up to 200 nautical miles, the maximum breadth of the EEZ as defined in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Where an actual continental shelf extends beyond that distance, a state can submit a list of points and supporting evidence to the CLCS to have that U.N. body issue a recommendation on the outer edge of the shelf's course. While the CLCS recommendation is technically non-binding, states generally follow the recommendation since this makes the outer limit permanent and unaffected by, say, receding coastlines caused by climate change. UNCLOS speaks only of a single continental shelf, but the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles is often referred to as an extended continental shelf and I will use that term here for clarity.

Second, delineation and delimitation are similar, but distinct, concepts when speaking of continental shelves. Delineation establishes the outer limits of the legal continental shelf. Delimitation, by contrast, determines the course of national boundaries on the shelf. To put it in terms of pie, delineation establishes how big the pie is, while delimitation decides how to cut each claimant’s slice.

What Does a Continental Shelf Claim Entail: Sovereignty or Sovereign Rights?

The most egregious mistake in discussions of continental shelf extensions is that the extension claims the water column, extends the exclusive economic zone and grants sovereignty. Examples of this mistake abound in writing on the Arctic, as illustrated above.

In fact, the extended continental shelf always ends at the water’s edge. Waters above the continental shelf more than 200 nautical miles from baselines are always high seas where foreign states and vessels enjoy high seas freedoms.

Instead, an extended continental shelf merely grants sovereign rights to all resources on and below the seabed. Although coverage often speaks of sovereignty, raising the apparent stakes, sovereign rights are not sovereignty. The coastal state does not “own” the claimed area. Rather, it gains exclusive sovereign rights to living and nonliving resources in the claimed area. That is why, despite claims to national ownership, no state will “own” the North Pole when all is said and done. Instead, one lucky state might have sovereign rights to living and nonliving resources on and in the shelf—but not sovereignty itself.

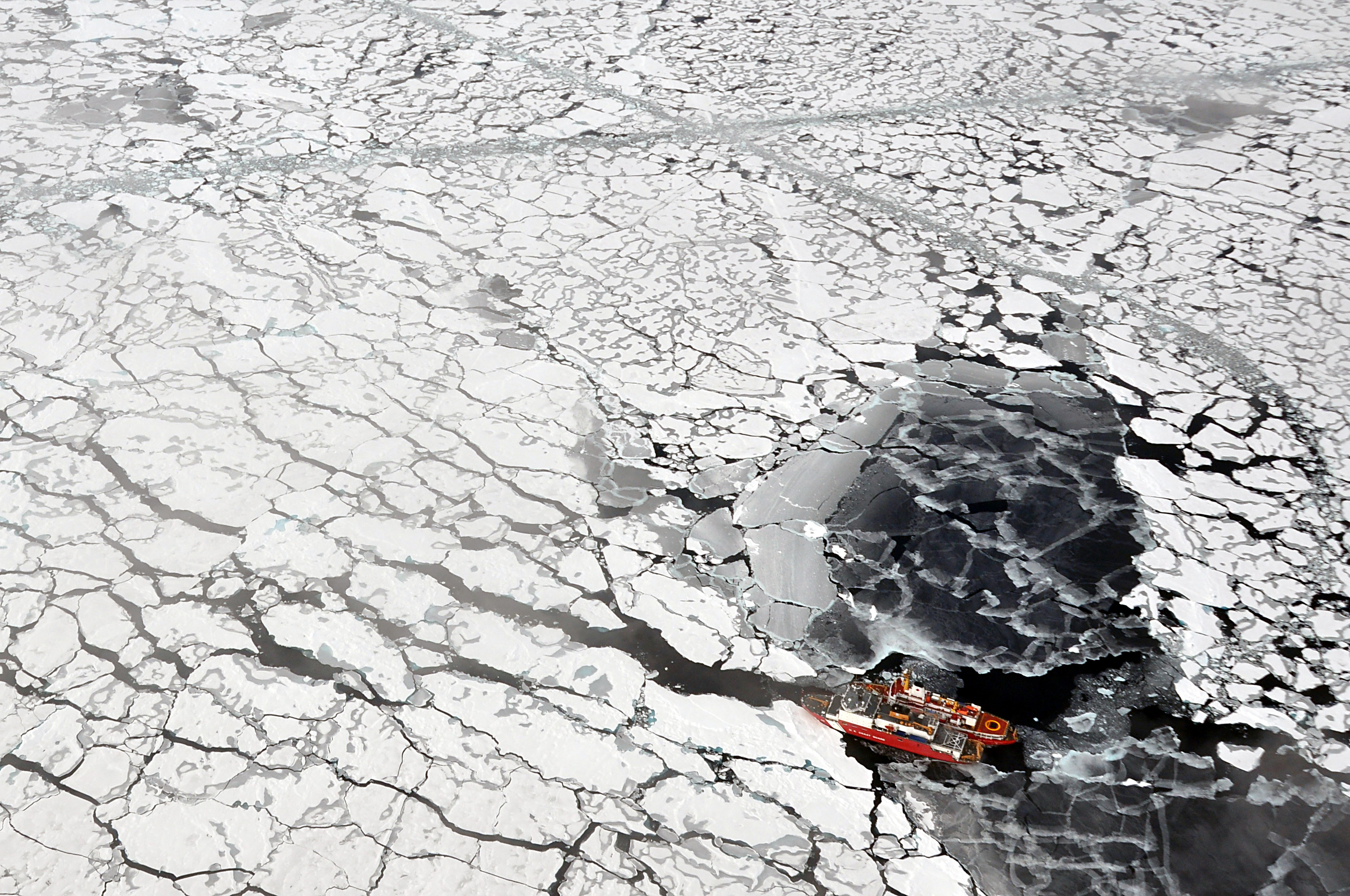

Every state with a coast in the Arctic Ocean appears eligible for extended continental shelves, and all but the U.S. have so far made the necessary submissions in accordance with the procedures laid out in UNCLOS Part VI. The U.S. is collecting data for its own claim, which it might submit despite not being a party to UNCLOS. As the image below on the left illustrates, the Russian, Danish and Canadian claims overlap under the Central Arctic Ocean. However, as as the image below on the right illustrates, the Arctic high seas are of considerable size and will be unaffected by extended continental shelf claims.

Source: The author. Data from Marineregions.com and CLCS submissions.

What Delimits the Shelf: the CLCS or Negotiation?

The second, but rarer, error exaggerates the CLCS’s role. In fact, the CLCS has a fairly limited role in the resolution of the Arctic shelf disputes. As its name suggests, the commission’s role is to delineate the continental shelf’s outer limit, not to delimit the continental shelf itself. To revive the pie analogy, the CLCS confirms the pie’s size, but the claimants will still have to agree on how to slice it up.

In the Arctic, Russia, Norway, Canada, Denmark and the U.S. are all cooperating to enable the CLCS to do its job. Where shelf claims are overlapping, Annex I of the CLCS’s rules allow the body to make recommendations on outer limits only if the coastal states make a joint submission or if none of the claimants objects to another claimant’s submission. In their notes to the CLCS responding to other claimants’ submissions, the U.S., Canada, Russia, Denmark and Norway have all consistently confirmed that they do not object to the CLCS acting on overlapping Arctic shelf submissions.

The onus will be on Russia, Canada and Denmark to delimit their overlapping claims either through negotiation or by going to a tribunal. Given continued ice cover, the economic incentive to settle the dispute to enable use is somewhat weakened. Still, in light of evidence ranging from the 2008 Ilulissat Declaration to the claimants’ diplomatic notes permitting the CLCS to proceed with delineating outer limits, all five states seem prepared to settle their dispute peacefully.

How Is the Shelf Delimited: Geology or Geography?

Assuming that the Arctic states do use peaceful negotiation or international courts, geography, not geology, will be decisive in determining the course of shelf boundaries.

Articles covering shelf extensions frequently mention the concept of natural prolongation—a doctrine that the continental shelf belongs to whichever state the shelf is a geological extension of. Such a doctrine requires claimants to prove that the soil of the shelf is an extension of the terrestrial soil. The much-trumpeted but legally meaningless 2007 Russian expedition to plant a flag on the seabed at the North Pole was designed to collect soil samples proving that the seabed there was Russian soil, deposited over millennia by Russian rivers carrying Russian silt into the Arctic.

Geology does matter for delineating the outer limits of the continental shelf, but it is of less relevance for delimiting competing claims. Both state practice and international court decisions have recently sidelined the doctrine in favor of equidistance-based delimitation.

States with overlapping extended shelf claims have negotiated delimitation where the dividing line is based on the geometry, rather than geology, of the coasts. In the 1990 U.S.-USSR maritime boundary agreement, the parties drew an equidistance-based boundary line that extends into the Arctic Ocean “as far as permitted under international law,” a clear reference to continental shelf entitlements. While Russia has yet to ratify the agreement, it used the agreement’s line in its 2015 CLCS submission. Likewise, the 2004 New Zealand-Australia maritime boundary treaty delimits their shared extended continental shelf with boundary lines rooted in equidistance.

In the limited arbitral practice to date, courts have also relied on geography over geology in delimiting competing extended continental shelf claims. In Bangladesh v. India, the Permanent Court of Arbitration rejected Bangladesh’s pleadings for an extended continental shelf based on the Bay of Bengal’s geology and opted instead to base its delimitation of the shelf on geometry rooted in geography.

One case is not definitive precedent, but combined with state practice it indicates strong headwinds against natural prolongation as a delimitation method. Some scholars argue that the court’s logic is faulty, but others have pronounced natural prolongation dead. Indeed, the court’s approach in the Bay of Bengal can be seen simply as the extension of the logic first introduced in Malta v. Libya, when equidistance trumped natural prolongation for shelf delimitations within 200 nautical miles.

Why Accuracy Matters

Accuracy on the nature of claims matters because it sheds light on a serious issue otherwise obscured by talk of “extended EEZ”—Arctic high seas fisheries. A 2018 agreement placed a moratorium on unregulated fishing in the Arctic high seas for at least 16 years, but the agreement may prove hard to sustain as ice melts and fish populations migrate farther north. Central Arctic Ocean fisheries will become a pressing policy issue that will require Arctic states to cooperate with the non-Arctic states that dominate global distant-water fishing. Furthermore, describing the dispute as one over sovereign rights rather than sovereignty itself will help lower the rhetorical and political stakes of compromise, by making clear that negotiations are about economic rights—not ownership of millions of square miles of “territory.”

Accuracy on the way claims will finally be resolved matters because it tempers the recent rise in alarmed rhetoric about great power competition over the Arctic. Since resolution of extended continental shelf claims will require multiparty negotiations, the situation has the potential to reinforce the region’s post-Cold War tradition of cooperation and multilateralism, rather than fracture it.

Regardless of how or when the competing Arctic extended shelf claims are resolved, they will likely be resolved peacefully. Indeed, Russia’s recent submission marks just the latest evidence of its intention to trust the process. Accurate descriptions of extended shelf claims will help correctly frame what is at stake and underscore that order and international law will guide the process.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the date of the Australia–New Zealand Maritime Treaty. An earlier version also omitted that CLCS findings are non-binding recommendations. The maps have also been updated.