Should American Spies Steal Commercial Secrets?

_-_flickr_-_the_central_intelligence_agency_(2).jpeg?sfvrsn=c1fa09a8_5)

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The past decade has almost completely overturned a generation of American consensus on the value of free markets and free trade. Both the Democratic and Republican parties have abandoned neoliberal economics in favor of trade protection and subsidies for strategic U.S. industries. This abrupt change of direction has a single cause: China, which used trade barriers and subsidies to fuel a sharp rise in its economic and military power. Faced for the first time in living memory with an adversary that may be as strong in the marketplace as on the battlefield, the U.S. is pivoting to much more explicit government support of its own strategic industries.

Ironically, that means the U.S. is now working from a Chinese playbook that China itself borrowed from American Cold War strategy. The Chinese call it civil-military fusion; the United States calls it the military-industrial complex. Either way, it means government support for advances in high technology that helps to bolster commercial and military capabilities.

When the Cold War ended, though, the U.S. shrank its defense sector to a handful of weapons makers while doing little to protect the commercial industries that make better weapons possible. Take the semiconductor industry as an example. Though it began in the U.S. with first Schockley and then Fairchild Semiconductor, the industry has since scattered abroad. The best machines for making chips come from the Netherlands; the most advanced chip manufacturing takes place in Taiwan. This story has been repeated in one high-tech sector after another, making everything cheaper but allowing governments that don’t play by free-market rules to manipulate markets for their own ends. By restricting Western sales of things like chips, electric cars, and artificial intelligence, China guarantees a market for its own companies and thus provides a technology base for China’s military machine. China made this strategy explicit in its 2015 Made in China 2025 plan, which outlined the industrial sectors it planned to boost first into independence and then to dominance.

The United States’s response was ad hoc but far ranging. It used sanctions and investment restrictions to hobble Chinese national champions. At the same time, it offered tariff protection and subsidies to industries—such as semiconductors, electric vehicles, and batteries—that have been targeted by the Chinese government. The U.S. response was not enough. As of 2025, most observers see Made in China 2025 as a success. Bloomberg, for example, assessed that China is now a global leader in five tech industries—including drones, solar panels, graphene, and high-speed rail—and competitive in seven more.

One part of China’s industrial policy that the U.S. has not yet imitated is commercial espionage. China’s formidable espionage machinery has been a major part of its commercial technology strategy. While Chinese intelligence has not ignored military technology—its hackers have stolen the plans for U.S. weapons systems including the F-35 and F-22 fighter and the C-17 cargo planes—Chinese espionage has focused even more heavily on civilian industries such as agriculture, biotech, health care, and robotics. Indeed, a detailed survey of Chinese espionage against the U.S. showed that half of the incidents were aimed at obtaining commercial secrets; only 30 percent sought military technology. China’s extraordinary espionage campaign is clearly paying dividends. In fact, the haul from its commercial espionage is so massive that China has built an elaborate pipeline for stolen intellectual property, providing the tech to two dozen scientific universities that obtain Chinese patents, which are then distributed to Chinese companies.

That raises a simple question: Should the U.S. add commercial and technological espionage to its strategy for countering China? This echoes a 50-year-old debate that emerged in the 1970s, when U.S. industry was succumbing to foreign competition and post-Watergate scandals left the intelligence community questioning its mission. Jimmy Carter’s CIA director, Adm. Stansfield Turner, asked his agency whether it should be stealing secrets for U.S. companies. He found little support at the time, but he returned to the idea in the 1990s. By then, the fall of the Soviet Union had left intelligence agencies struggling to find a role, and Japanese competition threatened many U.S. industries. In response, Turner asked, “If we spy for military security, why shouldn’t we spy for economic security?”

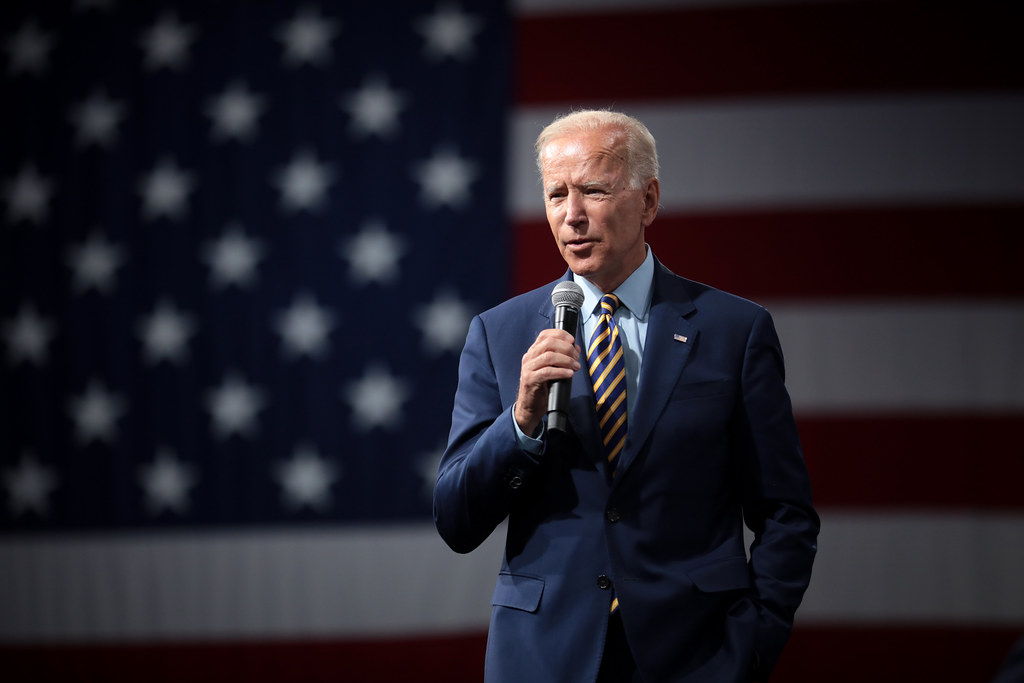

The answer, from policymakers and intelligence professionals, has so far been negative. Indeed, in a 2014 effort to lay the notion permanently to rest, President Obama adopted Presidential Policy Directive 28. PPD-28 expressly banned U.S. agencies from spying for the purpose of giving “a competitive advantage to U.S. companies and U.S. business sectors commercially.” The next year, he persuaded first China and then the Group of 20 to condemn cyberespionage conducted “with the intent of providing competitive advantages to companies or commercial sectors.” (The United Kingdom and possibly Germany extracted similar understandings from China.) Then, in 2022, President Biden adopted Executive Order 14086, which defined both legitimate and prohibited objectives for U.S. signals intelligence. Notably, one of the prohibited objectives was collecting “foreign private commercial information or trade secrets to afford a competitive advantage to United States companies and United States business sectors commercially.”

In fact, by the time the executive order was signed, the effort to create an international norm against commercial espionage was already dead. Four years earlier, Jack Goldsmith called the effort a failure in Lawfare, noting that “state-sponsored commercial cybertheft from China never came close to ceasing.” Goldsmith was right. Despite the unilateral limits imposed by President Biden on commercial espionage, neither the G-20 nor China have renewed their 2015 pledges, and there is no evidence that China’s economic espionage has receded.

So, is it finally time to abandon the taboo against commercial espionage?

Maybe so. Certainly a lot of the reasons given in support of the ban are looking a little threadbare.

One of the least persuasive arguments against commercial spying is the Biden-Obama notion that such espionage violates international norms—or would do if the rest of the world only had the United States’s fine-tuned moral sensibilities. That was never true. No country other than the U.S. has sworn off commercial espionage. Not even American allies: France and Israel are routinely accused of spying for their companies. Even the British have adopted a law expressly treating “the economic well-being of the UK” as a legitimate objective for intelligence operations.

What’s more, the Biden-Obama norm, on examination, turns out to be full of exceptions. It doesn’t prohibit economic espionage. Stealing commercial secrets is fine, U.S. intelligence agencies believe, as long as the secrets go to government policymakers. So too is collecting intelligence on foreign companies to catch them edging out U.S. competitors by paying bribes or evading sanctions. In fact, the Biden-Obama prohibition even allows intelligence sharing with the private sector for any purpose other than conferring “a competitive advantage to U.S. companies and U.S. business sectors commercially.” Such a narrow rule doesn’t exactly put the U.S. on the moral high ground.

Some might argue that debate about the wisdom of Executive Order 14086’s limitations on commercial espionage is no longer possible, because the limits were internationalized when the executive order became part of the U.S.-EU Data Protection Framework. I think that’s wrong. The framework creates safeguards around U.S. intelligence that are designed to meet European privacy standards, as outlined in a European Court of Justice ruling. To meet those standards, the European Commission concluded, U.S. law must limit government access to personal data to “what is necessary and proportionate to the public interest objective pursued.” The executive order meets this requirement by providing, among other things, a list of public interest objectives for U.S. signals intelligence. But the requirement that U.S. law set out the legitimate objectives of intelligence collection is not the same as a requirement that U.S. law adopt particular objectives, let alone that U.S. law identify prohibited objectives, as Executive Order 14086 does. Put simply, the European Court of Justice did not require, and the EU did not negotiate for, a limitation on U.S. economic and commercial espionage. The limitation was probably added by the Biden administration not so much to satisfy European law as to reinforce their failing norm against a future president with different views.

Another dubious argument for the ban is that commercial espionage poses an asymmetric threat for the U.S., which probably has more technology and commercial secrets than other countries. Maybe that’s a good reason for the U.S. to try to sell a norm against commercial espionage; it’s also a good reason for other countries not to buy what the U.S. is selling. With the exception of the Five Eyes intercept alliance, where deep intelligence interdependence makes collection against the other members impractical, the U.S. hasn’t found a lot of takers. And even for the U.S., the value of such a norm would be a wasting asset. Every year technological progress in the rest of the world erodes the United States’s technological advantage and thus the value of a ban on stealing tech secrets.

The last of the questionable arguments against commercial espionage is one that pervades the general counsels’ offices of the intelligence community. I heard it as far back as the early 1990s, when I was the National Security Agency’s (NSA’s) general counsel. Faced with Adm. Turner’s question, lawyers would respond by asking, “What if we manage to collect commercially valuable intelligence? Who do we give it to?” Veterans of many intelligence scandals, both real and imagined, the lawyers wanted to know how their agencies can justify giving a commercial advantage to one U.S. company and not to others.

There are a host of complexities in that choice. Not all U.S. companies are unambiguously American; they may have influential foreign shareholders or a non-American CEO, deep business ties to other countries, or simply such bad security that sharing intelligence with them would put sources and methods at risk. Or they may be too small or too far out of the technological race to use the secrets effectively. Making those judgments is hard. Justifying them to an angry member of Congress is harder. What’s more, like any government benefit, charges of favoritism will sometimes be true. If intelligence sharing is truly valuable, its distribution will inevitably be influenced by lobbying and politics. Better to just stay out of that thicket, many career lawyers believe.

That’s not really a legal argument, though. It’s cultural—the cautious advice of a risk-averse institution. Adding to this cultural reluctance is something intangible: the self-image of intelligence professionals, especially CIA officers. Former CIA Director Robert Gates expressed it pithily: “One of our clandestine service officers overseas said to me: ‘You know, I’m prepared to give my life for my country, but not for a company.’”

It would be easy to dismiss such remarks as a kind of government myopia, where injecting a bit of new information into a bureaucratic policy debate that will be relitigated every two years somehow means more than helping a strategic U.S. company stay ahead of a foreign competitor by five or 10 points of market share.

In short, the longtime taboo against commercial espionage deserves to be reconsidered. But maybe not to be discarded wholesale. After my career working with intelligence agencies, the most surprising and durable insight I’ve gained is this: If you want to be a good producer of intelligence, you need a demanding and sophisticated consumer of intelligence. That’s because a lot of secret information, including information that a target works hard to hide, isn’t actually very useful. And no matter how good a spy is at stealing secrets, he or she likely doesn’t know which nuggets matter the most.

I remember hearing that, as preparations for the first invasion of Iraq were coming to a head, intelligence agencies focused all their efforts on that country. They produced reams of human intelligence and communications intercepts covering leadership proclivities, social tensions, and order of battle. It was great stuff, a tribute to U.S. capabilities. But when all the intel briefings were over, a general who was about to send his heavy tanks into Iraq’s desert asked a question no one could answer. “All I really need to know,” he said, “is how deep the sand is.”

In this sense, the intelligence customer is always right. Only the customer knows which piece of intelligence matters most. Building a good intelligence program is a dialogue in which the customer must explain over and over why the intelligence, however exquisite, isn’t actually useful, and the intelligence officer has to keep adjusting his sources and methods and targets until the customer has what he needs.

That will be true of commercial intelligence too. Some closely guarded commercial secrets won’t help competitors who have different business constraints, some “secret” information may be obvious or useless to everyone else in that field, and some information may be secret today but public by the time it can be stolen, written up, and reported to the customer.

Put another way, CIA and NSA collectors can’t do commercial intelligence without being immersed in the commercial world. They need to be in the C-suite and the lab, delivering what they think the company needs and being told where they’ve fallen short. It’s intimate. And an intelligence professional who doesn’t think that helping commercial customers grab five points of market share is as honorable or important as impressing a deputy assistant secretary at an interagency meeting will never turn that intimate dialogue into great commercial intelligence.

Another danger is that intelligence professionals will acclimate to the commercial world too well. Understanding the value of business intelligence means understanding what it’s worth. And perhaps what it can be sold for. Chinese intelligence often fell prey to this temptation. It will be a while before we know why the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) lost its role as China’s premier cyberespionage organization, but I have long believed that a big part of the problem was what might be called crony cyberespionage. PLA generals who oversaw the hacking of Western companies realized that the stolen secrets had a dollar value; they could be sold to Chinese competitors. At some point, PLA hacking teams ended up embracing the intelligence priorities of the highest bidder. And when U.S. howls finally persuaded Chinese leadership to look seriously at what the PLA was stealing and where the data was going, President Xi Jinping may have realized how deep the risk of corruption ran. That would certainly explain the abrupt demotion of PLA cyberespionage units and the quiet substitution of teams from the Ministry of State Security. Maybe I’m wrong about that story, but I have no doubt that teaching intelligence officers to put a commercial price tag on what they’re collecting will create new risks for the intelligence community.

Breaking the taboo against commercial intelligence may still be worth trying, but with care. The question “Who gets the intel?” must be answered in a way that is fair and resistant to favoritism, that ensures an active and demanding customer, and that doesn’t cheapen the sacrifices made by intelligence professionals.

One way to discipline the collection and distribution of commercial intelligence is to treat the information like any other scarce government resource. The United States has decided to subsidize certain industries financially because their survival against Chinese competition is a matter of national security. Those are a good first estimate of the industries that deserve intelligence support as well. Why not begin by providing commercial intelligence support only to U.S. industries in sectors that have been targeted for national security reasons by China? It’s easier to justify government support for companies that are already under attack by an adversary government, and adopting such a policy might make U.S. allies less worried that it will steal their companies’ secrets too.

Another way to answer the question “Who do we help?” is to require an investment by the companies. Getting intel support can’t be a passive experience; companies will have to take the experiment seriously. They’ll have to make an effort to be a good customer. They’ll need to understand what our agencies can realistically collect, which means they must have individual and facility clearances. They’ll need better, and carefully audited, cybersecurity. And they’ll need to accept limits on foreign investors and other sources of foreign influence. Finally, they’ll have to be capable of winning, of making the government investment pay off in the same way that subsidies depend on a company’s market prospects.

Those kinds of requirements will reduce demand, but not to zero. The most likely customers for commercial intelligence are defense contractors and perhaps some defense-adjacent tech companies with dual-use technologies. If the U.S. is going to go down this road, and I think it should, that will be its first step.

-final.png?sfvrsn=b70826ae_3)