The State of State-Building in Afghanistan

At first glance, the Afghan state seems to be badly flailing, if not outright failing. Kabul’s politics are as divisive and paralyzed as at any time since 2001, while the Taliban presence is growing in the countryside. But beneath the turbulent surface, a widespread and abiding commitment to the survival of the Afghan state has emerged that merits recognition and support.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

At first glance, the Afghan state seems to be badly flailing, if not outright failing. Kabul’s politics are as divisive and paralyzed as at any time since 2001, while the Taliban presence is growing in the countryside. But beneath the turbulent surface, a widespread and abiding commitment to the survival of the Afghan state has emerged that merits recognition and support. As the Trump administration defines its mission and way forward in Afghanistan, it is important to acknowledge areas of concern but also those where progress is being made. In some cases, active engagement may be required while, in others, benign neglect may be the best approach.

Politics in Kabul is marked by a great deal of contention. The National Unity Government appears to be anything but unified, given the tensions that persist between President Ashraf Ghani and the chief executive, Abdullah Abdullah. And yet, despite their ups and downs, neither man has seriously threatened dissolution of the union; on the contrary, both seem to recognize that their political fates are inextricably linked, at least until Afghanistan's next national election.

Even if those at the very top prove able to work together, Afghanistan still must contend with its perpetual warlord problem. Vice President Abdul Rashid Dostum’s allegedly criminal behavior—he and his guards were recently accused of abduction, torture and sexual assault—earned him an indefinite time-out in Turkey. But soon after his departure, fellow strongmen, including his heretofore foe Gov. Atta Mohammad Noor, flocked to Ankara to show their solidarity, forging a new political coalition in the process. Another fearsome warlord, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, has returned to the political fold as part of a major reconciliation effort, disappointing those who had hoped the page was turning on Afghanistan’s dark chapters of predation and abuse. Yet their persistent involvement on the public scene reflects a fundamental recognition by these strongmen, among others, that their futures are plainly linked to the survival of the Afghan state. Rough as they may be around the edges, these men have (mostly) moved beyond picking up guns to resolve their differences and, instead, are wheeling and dealing in order to secure their place inside the government rather than working to overthrow it.

[T]heir persistent involvement on the public scene reflects a fundamental recognition on the part of these strongmen ... that their futures are plainly linked to the survival of the Afghan state.

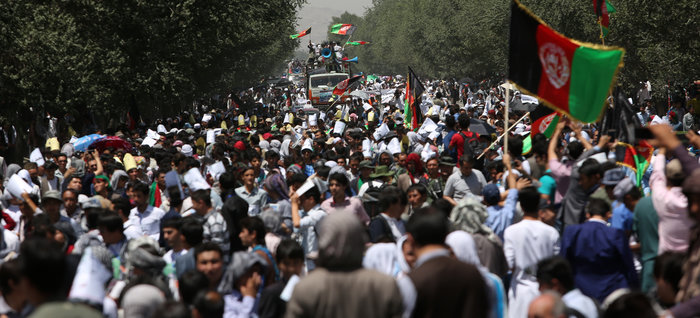

Many of the country’s most formidable elites may remain invested in the survival of the state, but that does not ensure security or stability. Life for many Afghans is still extraordinarily difficult. As in all insurgencies, popular disaffection fuels the fight, enabling recruitment and local cooperation. But in recent months social unrest has also found expression in Kabul in largely peaceful protests. A series of devastating terrorist attacks, coupled with broader disappointment in the government’s failure to deliver on many promises, brought thousands of politically disaffected Afghans to the streets. These demonstrations proved unsettling amid the tense security environment. But it was the Ghani government’s disproportionate—and, in some cases, violent—response to these protests that fanned the flames of anger, escalating tensions.

A closer look at the groups involved, including those known as the Enlightenment Movement and the Uprising for Change Campaign, reveals a burgeoning politics of peaceful protest, populated by educated, well-organized young people committed to claiming an unprecedented share of the public space. Some are organized along ethnic lines but all represent an effort to break from the traditional power brokers of the past, often along multiethnic lines. As such, efforts by factional heavyweights to coopt these protests to their own ends failed quickly. These fledgling movements assert the voices of a new generation that has benefited beyond measure from the fall of the Taliban. Their equities lie in the success of the state as a political space where new voices and ideas have room to grow.

Young Afghans demonstrate a brave and unwavering commitment to democratic politics in a variety of ways: Some organize in the streets; others work tirelessly inside government, through the press, and as entrepreneurs, artists and advocates. They remain dedicated, often at great personal risk, to preserving the transformational change their generation has experienced since 2001.

But this new generation’s commitment to progress cannot will away the problems that mark Afghanistan's political scene. Ghani, a president famed for his intellectual commitments to progressive politics and technocratic efficacy, is besieged by accusations of palace intrigue, ethnopolitical chauvinism and authoritarian micromanagement. Meanwhile, Taliban fighters persist in their struggle, wreaking destruction with the continued security of safe retreat into the borderlands of Pakistan. Their growing reach into northern areas is cause for alarm and adds to the burden of already-stretched Afghan national security forces. Few of the country’s problems can be solved by several thousand additional U.S. soldiers, despite the perennial debate this topic generates.

After more than 15 years of war in Afghanistan, the U.S. government and the American people must take a broader view and confront the international dimensions of war in Afghanistan. Despite the provision of close to $33 billion in military and economic assistance to Pakistan, the Taliban and Haqqani networks continue to enjoy seemingly unchecked sanctuary there. These groups are responsible for the deaths of more than 2,000 U.S. military personnel and tens of thousands of Afghan security forces, civil servants and ordinary civilians. President Trump and his administration seek to shake up the status quo at home and abroad. They have the chance to leverage American muscle and diplomatic creativity to rethink U.S. relations in the region.

National Security Adviser Gen. H.R. McMaster recently spoke of the president’s frustration with the “behavior of those in the region ... who are providing safe haven and support bases for the Taliban, Haqqani Network, and others.” He singled out Pakistan and the need for “a change in and a reduction of their support for these groups.” Lisa Curtis, National Security Council senior director for South and Central Asia, has also called on the Pakistani establishment to undertake “a comprehensive approach to shutting down all Islamist militant groups that operate from Pakistani territory, not just those that attack the Pakistani state.” Coalition Supports Funds have been withheld twice over Pakistan’s failure to uphold its end of the bargain in the U.S.-led effort to counter terrorist groups operating along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border. Absent genuine and decisive action against the Haqqani and Taliban networks—for example, the arrest of a senior leader—the $400 million allocated to Pakistan for 2017 should be taken off the table. Beyond the CSF, the U.S. government should consider other means of economic leverage—including aid from the International Monetary Fund and others, as well as punitive measures, including targeted sanctions—to reorient the calculus of those that support terrorism abroad. Otherwise, a “moral hazard” and the unchecked bad behavior that ensues will continue to define the relationship between these two countries.

The 21st-century version of Afghan nation-building is a project best left to the Afghan people.

The persistence of safe havens in Pakistan merits further escalation. The U.S. military should reserve the right to conduct cross-border military raids such as the ones that killed Osama bin Laden and Taliban leader Mullah Mansour. But these surgical strikes cannot stand in isolation; policymakers and military officers must connect the dots and confront the physical and political apparatus that has enabled such a long-standing haven to exist. This will require bringing diplomatic and military force to bear. The administration also must look beyond South Asia for answers. Given this administration’s interest in reframing U.S. relations with the Chinese, one productive avenue for dialogue may center on shared interests in Afghanistan’s stability and shared concerns about the spread of violent extremism, as well as China’s unique influence over Pakistan. The president’s commitment to deepening ties with the Saudis offers a similar opportunity to urge that government to use its influence in the region toward stabilizing ends.

At the same time, U.S. policymakers must recognize that many challenges endemic to Afghan politics are too complex for outsiders to understand, let alone influence to good effect. Past attempts to choose winners or broker coalitions have produced largely disappointing results. The 21st-century version of Afghan nation-building is a project best left to the Afghan people. Nonetheless, the United States and its allies are in a position to support those processes most likely to affirm the preservation and advancement of the Afghan state, a project for which there is widespread consensus.

Western governments can engage the Afghan state most effectively by remaining committed to those institutions and processes that have survived the surrounding turmoil and remain the key markers of fledgling democracy. They can help ensure that parliamentary and presidential elections are held in the coming years. Large numbers of Afghans, while fairly new to electoral politics, have come to recognize their right to exercise a vote as integral to their government’s legitimacy. Challenged by profound insecurity, fierce factional politics and even fraud, Afghans have demonstrated an exceptional commitment to vote for their president, parliamentarians and provincial council members. The international community must do what it can to provide the support and protection Afghans deserve in this brave endeavor. As Western aid steadily diminishes, foreign donors also have the opportunity to lend targeted, smart support (political, diplomatic, logistical and financial) to those individuals, organizations, firms and sectors—as varied as intrepid news outlets and technology start-ups to innovative artists and girls' robotics teams—that have the potential to transform Afghan democracy from a fantastical pipedream into a thriving and resilient reality.