Stormy Daniels Steps Down

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Previously on Trump New York Trial Dispatch: “Stormy Daniels Takes the Stand”

May 9, 2024

Back on Monday, the atmosphere around court had begun to feel routine—boring, even. The lines were short. The faces were almost all familiar. Only the hard-core Trump trials aficionados were going to show up to hear the accountants—though they are, in important ways, the molten core of the case.

Stormy Daniels’s testimony on Tuesday changed all of that and has created a new sense of excitement. The line is like a stampede today, one reporter quips as we race to the elevators on our way up to Courtroom 1530. Outside, the line for nonreserved seats is so long that the security guards have to turn away reporters. To give you a sense of just how hard it is to get in today, one member of the public personally hired a line sitter to get here at 3:00 a.m.

Daniels's testimony has drawn some new faces to the courtroom too. Arthur Aidala, the defense attorney who represents Harvey Weinstein, is today seated in the back row of the courtroom next to Andrew Giuliani. The two have been chatting for the past half hour. Boris Epshteyn is here too, but that’s nothing new. So is Alina Habba, who has made appearances before. But Rick Scott, the U.S. senator and former governor of Florida, is also here—for whatever that’s worth.

As Trump enters, a man in the gallery pews tries to greet him or say something to him. “SIT DOWN,” an officer yells. Trump spends a moment in the doorway before entering, talking to his lawyers, Emile Bove and Todd Blanche. He has a piece of paper in his hand that he is waving around.

At 9:17 a.m., the prosecution arrives. Assistant District Attorney Susan Hoffinger—who conducted the direct examination of Daniels—rifles through documents on the table, with Rebecca Mangold to her right. Joshua Steinglass, Matthew Colangelo, and Christopher Conroy are here too.

There is a tense moment when the sound of a camera phone shutter rings out. "Who was that?" a court officer demands angrily. Whoever it was is risking eviction from the court. To everyone’s surprise, a reporter immediately cops to the breach, but he has an explanation. It was not the sound of a phone camera shuttering; it was, rather, the sound of a laptop screenshotting. The court security guard looks over his shoulder and acquits him on the spot. Prosecutorial and police discretion at its very finest, folks.

Hoffinger and Susan Necheles of the defense chat briefly, both with papers in hand. Necheles handled the cross-examination Tuesday, and will presumably handle it today as well. Necheles then turns to talk to another member of the defense team, Gedalia Stern.

Trump seems in surprisingly good spirits, a stark contrast from his gloomy mood on Tuesday. He seems to crack a few jokes with Blanche to his left.

But now it is 9:29 a.m., and we all rise for Justice Juan Merchan, because it’s that time of day—which is to say the resplendent-in-his-robes hour. And he sweeps in. And he is, in fact, resplendent in each and every one of his robes. And judicial authority does, in fact, radiate from the core of his being. And he greets former President Trump. "Good morning, Mr. Trump," he says.

* * *

First up is a housekeeping matter. Hoffinger wants to talk about an exhibit with which the defense means to confront the witness today—to wit, an arrest record for Daniels from 2009, involving an allegation of simple battery with no injury from her ex-husband. Justice Merchan verifies that the arrest did not result in a conviction. "Anyone can be arrested. … That doesn't prove a thing," he says.

Necheles tries a different tack here, simply proposing to ask Daniels whether her ex-husband accused her of this conduct.

"It's not probative of anything," Justice Merchan says conclusively. This is a line of questioning he simply isn’t going to allow.

We turn to the request for limiting instruction, which Justice Merchan had raised on Tuesday as to aspects of Daniels’s testimony. He asks the defense whether it has considered the matter and decided whether to request a limiting instruction.

Necheles says she thinks it depends on where we end with the cross and asks whether she can defer the question until later. Justice Merchan agrees.

"Let's get the witness, please," the judge says.

* * *

Daniels strolls in. Her hair is down today, in loose curls. Her glasses are perched atop her head. She is wearing a green blouse with a black cardigan over it.

We left off on Tuesday with some texts between Dylan Howard and Gina Rodriguez—but Daniels was careful in her answers, saying she didn't know who this Howard guy was.

Yesterday, the cross was tense—even adversarial—from the start.

The jury enters the courtroom, and Necheles picks the narrative back up in 2016, shortly before the election. She displays texts again between Gina Rodriguez and Dylan Howard.

Gina Rodriguez: I have her

Dylan Howard: Is she ready to talk?

There's an objection, and Justice Merchan asks counsel to approach. A sidebar ensues, in which Hoffinger emphasizes that Necheles had Daniels read these texts the day before, and that these texts are not her testimony; Hoffinger accuses Necheles of “mischaracterizing.” Justice Merchan clarifies that Necheles can continue questioning if Daniels is aware of these messages, so long as she does not “do it in such a way that you’re putting their words in her mouth.”

Necheles tries again: You were asking for money, right? I never asked for money from Trump. I never asked for money from anyone in particular. I asked for money to tell my story.

But you entered a non-disclosure agreement? My attorneys did.

That was your choice, right? I accepted an offer. Daniels says her actual preference was to hold a press conference and just tell her story publicly.

You wanted to do that and make no money? It wasn't necessarily my choice. I wanted to do a press conference, but we were running out of time.

Didn’t you ask publications for money? I asked for money from publications to get the truth out, Daniels testifies.

You could've gone out at any time and done a press conference, no? I chose to be safe. I chose to accept the offer.

The tense atmosphere has already resumed, as Necheles and Daniels dig in for what will likely be a long cross.

During that time, were you talking to a Slate reporter? Yes.

And you told him about your affair with Trump? Yes.

He was my back up if the NDA didn't work out, Daniels says.

You could have just had Slate publish the story, Necheles points out, but they weren't going to give you money, right? But Daniels remains firm; her message is consistent if not entirely coherent: she wanted to get her story out, and the money was secondary.

Necheles asks: Isn't it correct that you told Jacob Weisberg, the Slate writer, that as an alternative to be paid for your silence, you wanted to be paid for your story? Daniels says she doesn’t think she said that, and Necheles shows her a document to refresh her recollection. I don't remember saying exactly that, no, Daniels says—standing her ground.

And didn’t the Slate reporter say, Necheles pushes, that his publication doesn't pay for stories but that you should come forward anyway? Yes. Says Daniels: I wanted the truth to be printed with a paper trail of some sort—whether a video, an interview, or something else.

Necheles has an alternative explanation: Daniels wanted money for the story. Daniels responds that the NDA ended up being the better alternative to "protect my family."

Necheles goes on. Didn’t you also tell Weisberg that another motive was your anger about Trump's opposition to abortion and gay marriage? I don't remember saying that, Daniels laughs.

Necheles displays evidence for Daniels, presumably of Daniels saying that her motive was also political anger, but Daniels reiterates: She doesn't remember saying it.

Necheles asks if Daniels was furious when Michael Cohen kept delaying payment for the agreement. Daniels acknowledges this point.

Didn't you scream at your lawyer, Keith Davidson, and call him a pussy? Daniels smirks and asks: Can you show me where I said that? Necheles displays a transcript.

We see a transcript from April 2018 of a conversation between Davidson and Cohen, and begin to hear a clip of Cohen, but Necheles cuts it off. A mistake.

We hear another voice now—Davidson’s—begin to speak the words on the transcript, but Hoffinger quickly objects. Justice Merchan sustains the objection. A sidebar ensues in which Hoffinger points out that the tape Necheles has played before the jury has “nothing to do” with the question Necheles asked, nor does it have a mention of the witness. Necheles apologizes for playing the wrong tape and needs to find another transcript. “There’s one where she’s calling him a 'pussy,'” she says. Justice Merchan offers a warning that the defense needs to be more careful before putting exhibits up on the screen. The sidebar ends.

Justice Merchan directs Necheles: Can you look at the transcript first before you play the tape?

Necheles clarifies that she’s talking about F17-ET. Behind her glasses, Daniels narrows her eyes as the clip begins again:

Davidson: I just didn’t want you to get caught off guard, and I wanted to let you know what was going on behind the scenes. And I would not be the least bit surprised if, I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised if you see in the next couple of days that Gina Rodriguez’s boyfriend goes out in the media and tells the story that Stormy Daniels, you know, in the weeks prior to the election was basically yelling and screaming, and calling me a pussy.

Cohen: Can I ask you a question? Right.

I never yelled at Keith Davidson on the phone, Daniels says, and she further says the transcript makes clear that it was Gina Rodriguez's boyfriend, not her, who was the one who was going to tell the story in the media.

But you got $130,000, right? I didn't. That was the payment, Daniels quips. I received less than that.

So far today, Daniels seems to be taking a page out of Davidson's book, playing "lawyer games" with Necheles. Exploiting technicalities, being ultra precise, not giving an inch. She’s holding her own.

Necheles shows her the NDA, which names "Peggy Peterson" and "David Dennison," aka Daniels and Trump. You understand that a contract is a legal agreement? Well I'm not an attorney, but yes, Daniels says.

She starts walking through the language in the agreement, asking Daniels questions about some of the legal language contained within it. Like I said, I am not an attorney, so I'm reading this quickly, but I signed this based on my attorney's advice, Daniels says.

What you've been saying here is you're not a lawyer and these were legal terms you don't feel comfortable discussing? Not without speaking to my attorney, no.

And this is a legal contract? Yes.

Necheles pulls up the January 2018 Wall Street Journal article about the Daniels payment. She also displays the statement Daniels signed in response to inquiries that led to the story. Recall that this is the denial statement to whose truthfulness Davidson implausibly attested a few days ago. Necheles then reads the follow-up denial statement from Jan. 30, 2018, the day of Daniels's Jimmy Kimmel show appearance, the one she says she signed in an abnormal way as a tipoff that it was not true.

Necheles now begins a new line of attack: Trump's denial in 2018 of the encounter couldn't have been about election interference, because there was no election. Wasn't he concerned about his family, and about his brand? Daniels says he never mentioned anything about his family, and that she wouldn’t know what he wants to protect.

After you received a lot of money, you wanted to publicly say you had sex with Trump right? No, I wanted to publicly defend myself.

You wanted to make more money? No, that's why I did 60 Minutes for free.

Isn’t that around when you hired Michael Avenatti? Yes, Daniels says, a bit disgruntled, with very noticeable disdain in her voice.

Necheles walks Daniels through questions to highlight the defense’s narrative that Daniels has profited off of telling stories about Trump.

After the Anderson Cooper appearance, you got a $800,000 book deal to sell your story, right? I sold my life story, yes.

Wasn't sex with Trump the centerpiece of that? No.

Necheles asks whether Daniels thought people would just buy her book to read about sex with Trump, given that Chapter 3 of the book starts with a joke that the reader probably skipped right there to just read about that sexual encounter. Daniels says she doesn’t know if she believed people were going to buy the book just for that story. “Sadly, I thought that's what a lot of people would turn to first,” she says.

Necheles displays a flyer for a Daniels book event at a strip club, with the golf club photo of her and Trump and the caption: January 20th Making America Horny Again! Daniels testifies she never used that hashtag, in fact she hated it, and she had no control over how clubs promoted the book or her appearances. She also says she never used that picture.

Necheles has seemingly abandoned for now the line of attack she started the cross with, which involved the money Daniels owes Trump. She is now pursuing a related narrative of a money-hungry Daniels, looking to make a quick buck off of her salacious Trump story with the #Resistance crowd.

She turns to the Daniels documentary, for which Daniels was paid for the rights to her book. Asks Necheles: You were having an affair during the filming right? Daniels was involved with a cameraman, she acknowledges, but clarifies that she was separated from her husband at the time.

Necheles is asking her about the amount of money she received for selling the rights to her book for the documentary.

Didn’t you receive $125,000 for the rights to your book? Not yet. I haven’t received all the payments.

How much of it have you received? $100,000 for back footage, but I was not paid for an interview.

But you were paid for the rights to your book, right? That was part of my contract. You’ll have to ask my attorney.

But you received $120,000 from the documentary people, right? A lot of it was footage I had to reimburse the cameraman for.

So, the answer is yes? "Not exactly. You're trying to trick me into saying something that's not entirely true," Daniels objects.

Necheles asks about documentary promotion events: You have become a hero at those parties for Trump haters? I don't know, I don't speak for them.

You are continuing to this day to make money off a story that you promised would put President Trump in jail? No.

Necheles displays a tweet by Daniels, responding to someone calling her a human toilet: "Exactly! Making me the best person to flush the orange turd down."

When Necheles says this is about Trump, Daniels responds that she never actually said that she was talking about Trump. That’s your interpretation, she says to Necheles, which gets a good laugh.

Necheles now asks about Daniels’s alleged social media posts claiming that she would be “instrumental” in putting Trump in jail. But Daniels balks, saying she doesn’t think she has said such a thing. Necheles is showing her an exhibit to refresh her memory, but neither "instrumental" nor "jail" features in the "orange turd" tweet and Daniels responds to this exhibit by saying: “You’re putting words in my mouth.”

Necheles runs through some more social media posts from other users calling Daniels other names, and asks if they could serve as examples of something she might have responded to. "I respond to hundreds of tweets like this calling me names," Daniels says.

At the end of Tuesday, Necheles was beating up on Daniels pretty aggressively. Today, by contrast, the witness is more than holding her own. Gone is the apparent nervousness of Daniels on direct examination. She’s not talking way too fast any more. She’s not going off on tangents. She’s combative and funny. She is calling out Necheles on her mischaracterizations of the record. And she is not intimidated to go toe-to-toe with her on the interpretation of documents or events. She is also unfazed by being called on her contradictions and implausibilities in her own story—which are numerous. In a fashion that Trump would have to acknowledge as professional, she just brazens it out.

We have a brief sidebar. Hoffinger objects to the defense presenting Daniels’s social media posts without context. She claims that Daniels’s posts are often in response to threats from other people, and these exhibits fail to make clear what she is responding to; Hoffinger says that this is creating an impression with the jury. Necheles says that she can include the post that Daniels’s post was in response to, to which Justice Merchan says she can do later. Objection sustained.

Necheles resumes. When Trump was indicted, you celebrated on Twitter by pushing merchandise from your store? I tweeted that he was indicted, yes, and people asked how they could support me, so I added the link to my store. We see some of Daniels' tweets. For example:

That's you selling your merchandise, right? That's me doing my job.

You have an online store—much of the merchandise is you bragging about how you got Trump indicted, right?

Daniels responds with an ironic rhetorical question: “I got President Trump indicted?”

In response, Necheles displays a "Stormy Saint of Indictments" candle from her store.

"Oh my god," a member of the public exclaims. It is unclear whether he is disgusted or whether an impulse purchase is going to happen as soon as court lets out. We see a string of #TeamStormy shirts, Stormy Daniels comic books, and more.

"Keep in mind, I did not write this comic book," Daniels says. She also clarifies that she didn't make the candle either.

Necheles asks about two forthcoming books—the autobiographical "Rockstar Pornstar" and a novel. She also asks Daniels about her TV show formerly known as "Spooky Babes," about the paranormal, and she notes as well that Daniels was on a podcast in which she claimed to be able to speak to dead people. Necheles asks about Daniels’s claim that spirits attacked her then-boyfriend and held him underwater.

Daniels confirms the claim and asserts that the New Orleans house she lived in at the time had “some very unexplained activity,” so she decided to create a show to investigate it. She jokes that a lot of the supposed "paranormal activity" in the show was debunked; in one instance it was just an opossum under the house—which sparks laughter from the press. Necheles moves to strike Daniels’s answer from the record and asks Merchan to instruct her to answer the question. Justice Merchan declines.

You read oracle cards for clients? Yeah. She reads tarot cards. You tell people you can speak with their dead relatives? Yes. And they pay you money for it? Yes. It's one way she makes money.

With this line of questioning, Necheles is clearly trying to portray Daniels as a serial fabulist who has made her living off of phony stories about, among other things, paranormal activity and sex with former presidents.

Necheles asks Daniels about her extensive experience in the adult film industry.

You have a lot of experience in making phony stories about sex appear to be real, right? “Wow,” Daniels laughs. “The sex in the films, it’s very much real. Just like what happened to me in that room.”

You bragged about how good you are at writing good stories and dialogue in “porn movies,” right? Yes.

And now you have a story you’ve been telling about having sex with Trump, right? "And if that story was untrue, I would have written it to be a lot better,” Daniels quips, delivering it like a punchline.

We're back in the hotel suite now—details of which, such as the black-and-white tile of the floor Daniels described Tuesday. Necheles asks whether as part of her witness prep, she was coached to include such details. Daniels shoots back: There's nothing wrong with preparing a witness.

Necheles responds: That wasn't my question.

Necheles continues to search for chinks in Daniels's armor, the inconsistencies between small details in her testimony and her book, saying that she was coached to "match" the details. I don't need to match details to my book, because that's the story, Daniels says.

Your story about President Trump has changed a lot over the years, right? No.

You met him at a golf tournament at Lake Tahoe? Yes.

Necheles asks whether Daniels met other celebrities there, name-checking more athletes and big names: Aaron Rodgers. Dan Quayle. Drew Brees. Charles Barkley. Big Ben again. Daniels is sure about Barkley and Big Ben, unsure whether she met Rodgers, Quayle, and Brees. There were a lot of celebrities there.

Necheles begins to retrace the steps that led to the hotel suite.

Trump's bodyguard (Keith Schiller) invited you to dinner right, not Trump? Yes.

Your testimony was that you said "fuck no," but you gave Schiller your phone number anyway? Yes.

Necheles emphasizes the inconsistencies: Isn't this a totally different story from the one you told in 2011? No.

Didn't you tell InTouch magazine in 2011 that Trump himself asked you to dinner? I don't remember saying that, Daniels replies. It was Keith.

Necheles displays the article from InTouch, reading a quote from Daniels: "He came to talk to me and asked for my number and I gave it to him." I didn't specify who, Daniels explains.

Well, you didn't mention the bodyguard in that paragraph, did you? They asked me not to mention other people.

You also testified that you said "fuck no" when asked to dinner? Yes.

But you told InTouch in 2011 that you said "of course"? Yes, those were the words of my publicist. This is an entertainment magazine, it's short and frivolous. It's repeating the story in an entertaining way.

This has been a constant strategy in the cross—pinpointing each time Daniels's story changed, and exploiting it. Necheles’s cross is consistent and fast-paced. Her questioning is swift, sometimes even cutting of Daniels before she can finish her answer. "Can we let the witness finish?" Hoffinger cuts in at one point. “Please,” affirms Justice Merchan. Necheles continues to pepper Daniels with question after question, each picking a different nit with her seemingly conflicting stories.

Another inconsistency: dinner vs. no dinner. Necheles reads Daniels's statement on the Kimmel show, in which she said that while she went to Trump’s room for dinner, she never got dinner. You said you never got any dinner at the hotel room? Yes.

And you wrote in your book that you were hungry? Right.

You at least needed a bag of pretzels? Yes.

It was a big deal that you didn't get dinner? "I went to dinner, and didn't get dinner."

You told Jimmy Kimmel you are very food motivated? Yes. Daniels giggles to herself about her wit as to her food-driven actions.

But Necheles now confronts her with what she said on the subject in 2011. According to Necheles, Daniels told InTouch in 2011 that she had dinner at the hotel. "I had dinner with him but I can't remember what we had."

You said that? Yeah. It says I don't remember ordering anything. It was dinnertime in the room. I had "dinner" in his room but we never got food and I never ate anything. Having dinner where I'm from doesn't necessarily mean you put any food in your mouth, Daniels continues. You go to someone's house at dinnertime, that's dinner.

Even 18 years later, Daniels still seems genuinely annoyed that she never got to eat dinner that night. We had "dinner time" in the room but not "dinner," Daniels says.

“Your words don't mean what you say do they?” Necheles says bitingly.

The prosecution’s objection is sustained.

Another contradiction it is important to Necheles to bring out: Daniels's method of transportation to the hotel suite. In her testimony, and her more recent interviews, she has said that she came first on foot, and in heels, stopped at a tattoo shop to visit friends “for like an hour,” and then had a car take her the rest of the way. But in 2011, in the interview for InTouch magazine, Daniels mentioned only the walking part. She also mentioned only walking in her book. And then—when interviewed by prosecutors for this case, according to Necheles—she said that Trump’s bodyguard sent a car to pick her up.

The defense strategy today is coming into focus: Daniels is both an unreliable witness with a bad memory and a vindictive, money-motivated liar. She can’t remember details consistently, Necheles is trying to argue, because the whole story is made up.

The problem for Necheles is threefold. The first issue is that Daniels is giving no ground; she is as unflustered by apparent contradictions as Trump would be. A second is that Necheles is relying almost wholly on the 2011 InTouch interview to show these contradictions. A reasonable juror might determine that this interview is an outlier against a set of subsequent statements that are relatively consistent with one another. The third issue is that Necheles risks coming off as raising a set of picayune conflicts in testimony concerning events that took place 18 years ago—about which the big picture is quite consistent over time. While Necheles is hoping jurors will react to these contradictions by disbelieving the witness on her big-picture story, they also might react to this relentless focus on minutiae by getting annoyed with the defense’s instinct for the capillaries.

Necheles does not seem concerned about this possibility.

She now turns to Daniels's account of her sexual encounter with Trump. You act in porn? Yes.

With naked men and women? Yes.

But you said the sight of a man in his boxers when you exited a bathroom almost caused you to faint? Yes, when you're not expecting a man twice your age, it can be jarring.

Daniels talks about the power differential between the two of them. He’s much larger than she is.

Necheles asks: But in your book, you wrote that you made him "your bitch"? That was earlier.

But now that he was in t-shirt and boxer shorts, you got so upset that you couldn’t speak up and say no? Correct.

The lawyer zooms in on Daniels’s contention that she blacked out in the middle of the encounter. Daniels is answering more quietly now, and more coldly. "Like I said, there were parts in the middle that I didn't remember," Daniels says.

Necheles continues to pick at inconsistencies between the 2011 InTouch interview and her claims now. In her testimony, Daniels says that Trump stood up from the bed, but in the InTouch interview, there was no mention of standing. You never told InTouch magazine anything about Trump standing up and blocking the doorway? It's an abbreviated version of the story, Daniels remembers; they left out a lot of stuff because they couldn’t fact check it.

And nothing about a trailer park? No.

So you made all of this up? No.

You weren't drinking that night? No drugs? No, just water. I was not given any drugs and didn't take any. I don't believe there was even any alcohol in the room.

The two continue to talk at the same time, and Justice Merchan asks for only one person to speak at a time. Both agree, and apologize.

Now we’re back to Weisberg's Slate piece: Didn't you tell Weisberg there was no abuse, and you were not a victim? Yes.

You said the worst Trump had done was break promises you never believed he would fill? Yes.

And you told Weisberg Trump offered to buy you a condo in Florida and promised you to put you on "The Celebrity Apprentice"? Yes.

Nothing about a power imbalance, or being scared because there was a bodyguard standing outside the door? No. I said the worst thing he did was lie.

You were interviewed by Vogue in 2018? Yes.

And you were asked if Trump did anything that made you feel like you had to have sex with him, and you responded “No. Nothing.” Correct? Yes.

But on Tuesday you said he stood over you, made nasty comments, and you felt a power imbalance? My own insecurities made me feel that way. I have maintained he did not put his hands on me, he did not give me drugs or alcohol. I was not physically threatened or drugged or drunk. My own insecurities in that moment kept me from saying no.

Asks Necheles: Your story has completely changed hasn't it? No, you're trying to make me say that it changed, but it hasn't changed, Daniels fires back.

Fast forward to the brief hotel lobby nightclub meeting with Trump and Ben Roethlisberger. At that point, you really believed Trump wanted to put you on "The Celebrity Apprentice"? Yes.

We jump around again, to various phone calls between Trump and Daniels.

Justice Merchan calls for a break, and several reporters make a run for the door. It’s hard to tell who is having a bladder emergency, and who is racing to file stories. For some, we might have both issues going on at once.

* * *

"Can we get the witness, Ms. Necheles?" Justice Merchan says, after a brief intermission.

Daniels enters the courtroom once again and takes her seat. As she picks at something caught in her eye, Necheles resumes with the "Make America Horny Again" tagline, which Daniels says she hated and didn’t create—in fact, that she fired someone for posting at one point.

Daniels is calm and polite, she says "yes ma'am" to one of the questions.

Necheles displays an Instagram post of Daniels's. It's from February 2, 2018, and is a flyer for an event with that same tagline, "Make America Horny Again 2018 Tour." Daniels clarifies that it's not on her personal Instagram. This is her business Instagram.

Necheles displays another post on what she terms Daniels's "public Instagram" page shortly thereafter, with a slight variation of the tagline: "Making America Horny Again Tour."

You were making money off of that right? That's what you do with tours.

President Trump was the biggest celebrity at that golf tournament right? It depends on what you're a fan of.

But a lot of people recognized him, followed him around? Yeah, a lot of them were paid to follow him around. I don't know.

You said Keith Schiller was there when you went to Trump's hotel room, standing outside the hotel suite? Yes, he was leaning against a wall by the door.

When you went into Trump’s bedroom, it was far away from Keith Schiller, right? I don’t know where he was.

You didn’t see him inside the suite? I never saw him inside, no ma’am.

You said one reason you thought that you couldn’t leave was because Schiller was outside the suite? Absolutely. I would have had to pass by him and wait for an elevator to leave. He's a very large man.

But you emphatically told Vogue in 2018 that you never felt any physical danger? You recall saying that? Yes.

This is not going well for Necheles. But as we jump around in time and topic, it’s impossible to know how and whether the jury is processing this. It's a bit difficult to re-situate oneself in the narrative every time we skip from one event to another, and the relevance of many of Necheles's questions is not immediately clear.

Necheles now returns to the NDA, and to a point that is pivotal to the case. You have no personal knowledge about his involvement in that transaction or what he did or didn't do? Not directly, no.

You didn't negotiate the NDA with Trump? No, through my attorney.

And Cohen paid you, not Trump? Right.

You understand that in this case, Trump is charged with a crime for how a payment reimbursing Cohen is "labeled" on Trump's books? I'm not an attorney.

Even though you tweeted and celebrated about his indictment? There were a lot of indictments. (Another big laugh.)

And you don't know anything about Trump's business records? No, I don't know anything about that.

Necheles goes in for the kill: "Ms. Daniels, you have changed your story many times. And isn't it a fact that the reason you changed your story many times is because you never had an affair with President Trump, but realized that you could earn money by saying you had an affair, and you have been doing that for 12 years?”

Hoffinger objects. Sustained.

A sidebar ensues, at which Hoffinger calls back to the various tweets the defense questioned Daniels about before. She wants to admit two exhibits so that jurors can understand the context that Daniels was responding to on social media, and wants to elicit at least two questions about what each tweet was in response to. Necheles does not object, and Justice Merchan allows it. Hoffinger then also asks to elicit questions about the effects that online threats have had on Daniels and her family. Necheles objects, arguing that it would be “so highly prejudicial.” Justice Merchan cuts in and tells Necheles that she did a good job of establishing before the jury that Daniels was “doing all of this for money” and asserts that it’s thus fair for the prosecution to attempt to demonstrate that she has suffered injuries as a result. Merchan allows Hoffinger’s questions in redirect.

Necheles is done.

* * *

Hoffinger begins her redirect exam. Defense counsel asked you quite a lot of questions Tuesday, and today as well, about whether fear played into you signing the NDA?

An objection is overruled.

Your attorney friend advised you about "hiding in plain view," Hoffinger asks. Can you explain that? It just means hiding in the open, that nothing will happen to you if everyone is watching.

So part of entering into the NDA was to make sure it was all documented in public? Yes.

This, of course, doesn’t make a lot of sense, since the effect of the NDA was to cause Daniels’s story to not be documented in public.

Hoffinger goes on to clarify why then Daniels also took the money? Well, everyone is happy to take money, Daniels responds, in a relatable tone.

Now we see the texts between Rodriguez and Howard, whom Daniels says she doesn't know, once again. You indicated that the InTouch article was a "very light article" for entertainment purposes? Yes.

Hoffinger shows the article to the witness and focuses on the very bottom of it, which says: "This interview has been lightly edited." Do you recall this? Yes.

Did Ms. Necheles ask you any questions about that statement saying the article has been edited? No.

Defense counsel asked you a lot of things that you did and didn't say in 2018, Hoffinger says. You didn't tell every single detail to Anderson Cooper, right? Correct.

But you mentioned a lot of details?

An objection, for leading the witness, is sustained.

Hoffinger now tries to enter an exhibit—the 60 Minutes interview—into evidence, which elicits an objection and a sidebar conversation. At the bench, Hoffinger explains that the exhibit contextualizes a “so-called inconsistency” in Daniels’s story that the defense had pressed her about. After reading the relevant case law, Justice Merchan decides to err on the side of caution and deny the application. He instructs the prosecution to address Daniels’s points that they believe were taken out of context to put them in context.

Before Hoffinger resumes her questioning, Justice Merchan says: "Ms. Hoffinger, you can clarify to the extent that we discussed, and to that extent only."

The defense asked about certain things you didn't tell Anderson Cooper, but you told him a lot of things, didn't you?

An objection is overruled.

You did tell him you had sex with Trump, and provided details about the room? I did.

And you did say that Trump never wanted to keep it confidential?

An objection produces another sidebar.

"I'm so hungry," Daniels whispers, who still appears to be food-motivated.

At the sidebar, Necheles does not appear to be food-motivated. She argues that Hoffinger’s questions “have nothing to do” with what she addressed in her line of questioning. Necheles says Hoffinger is having Daniels go back and say that the details about the encounter she never mentioned “were actually things that she said before and that’s improper.” Justice Merchan instructs Hoffinger to “establish that she established a lot of details and leave it at that.”

Back before the jury, she asks: So you did tell Anderson Cooper about your encounter and other encounters with Trump? I did.

Hoffinger pivots back to Daniels’s social media posts—the same ones Necheles was pressing her about just minutes ago.

The defense asked you some questions about a post you made saying, “I will dance down the street when [Trump] is selected.” Do you remember those questions? Yes.

And you recall that you said you were only responding to someone and using the same words as the person who tweeted at you? Yes.

Hoffinger enters another exhibit into evidence—it’s a screenshot of a tweet from a user called “Intergalactic Gurl” calling Daniels a “disgusting degenerate prostitute.” In another tweet to Daniels, Intergalactic Gurl wrote, “Good luck walking down the streets after this.” Daniels clarified that she interpreted this as a threat, and that this was the tweet she was responding to when she used the term “selected.” Hoffinger displays yet another message from Intergalactic Gurl to Daniels.

And did this person also tweet, “No wonder Glen left you?” Yes.

And what did you interpret that to mean? That there is no surprise my daughter’s father left.

Hoffinger points out that for each of these tweets, Necheles never asked about the initial tweet, only Daniels's replies.

Hoffinger then pulls up yet another derogatory tweet toward Daniels to which Daniels replied.

Were you responding to someone calling you an “aging harlot?” Yes.

Are the aforementioned tweets examples of messages from random individuals in relation to things that you have said publicly about Trump? Yes. These are tame, actually.

Hoffinger pulls up another exhibit. We now see Trump's post on Truth Social: "IF YOU GO AFTER ME, I'M COMING AFTER YOU." And Hoffinger asks Daniels about it.

Daniels says she understood it to be about her, because it was around the time of Trump prevailing in the Florida defamation case involving Daniels.

You had nothing to do with the charges in this case, right? You did not testify to the grand jury? I did not.

Hoffinger now asks Daniels to clarify why this whole ordeal has cost her a lot of money.

I've had to hire security, take extra precautions for my daughter, and move her to a safe place to live. I’ve had to move a couple of times. I lost on the judgment on the NDA case and owe attorney's fees.

Hoffinger asks: Has your public telling the truth about Trump been a net positive or a net negative in your life?

An objection is overruled.

Daniels responds: Negative.

"Nothing further," says Hoffinger.

Necheles is back up immediately. We see the “Intergalactic Gurl” tweet again, and she asks Daniels whether this kind of thing happens a lot on Twitter. It does, she acknowledges.

We see another Daniels reply: "you sound even dumber than he does during his illiterate ramblings." That's you being nasty back, right? Yes.

Someone you don't even know, you're calling them names? You prided yourself in your witty answers? You were attacking them right back? I was defending myself.

Necheles displays more tweets of public sparring between Daniels and strangers on the internet before coming back to "IF YOU GO AFTER ME, I'M COMING AFTER YOU." This doesn't say your name, does it? No.

Do you realize at the time there was a Republican PAC coming after him at the time? No.

No further questions, and Hoffinger is back at the lectern.

Hoffinger displays a split screen: People's Exhibit 408A, which is Trump's Truth Social post calling Daniels "horseface" and "sleazebag," next to Defense Exhibit J2, which is a tweet by Daniels.

What was the date on Trump’s post calling you a Horseface and a SleazeBag? March 15, 2023.

And what is the date of your post in Exhibit J2? March 21, 2023.

So how many days later was your post after Trump’s? Six.

Nothing further. Daniels steps down.

If David Pecker and Michael Cohen are the essential factual witnesses in this case, Daniels is the essential atmospheric witness. Her testimony does not establish any of the elements of the offense; it does not address whether Trump personally directed Cohen to buy the rights to her story or, more critically, whether Trump directed Cohen and Allen Weisselberg to engage in the reimbursement scheme. But her testimony is aimed at addressing Trump’s motive. Why was he so keen to prevent her story from coming out on the eve of the election, when he seemingly wasn’t so worried about it before?

In a cultural sense, her testimony is a kind of moment. She sat on the witness stand in front of the former and would-be president and told her story. His lawyer tried to destroy her with a sledgehammer—and with a thousand paper cuts. And neither quite worked. We won’t speculate as to how the jury understood her testimony, but she was certainly not vanquished.

* * *

"People, please call your next witness," says Justice Merchan.

"The People call Rebecca Manochio."

Mangold begins her direct examination.

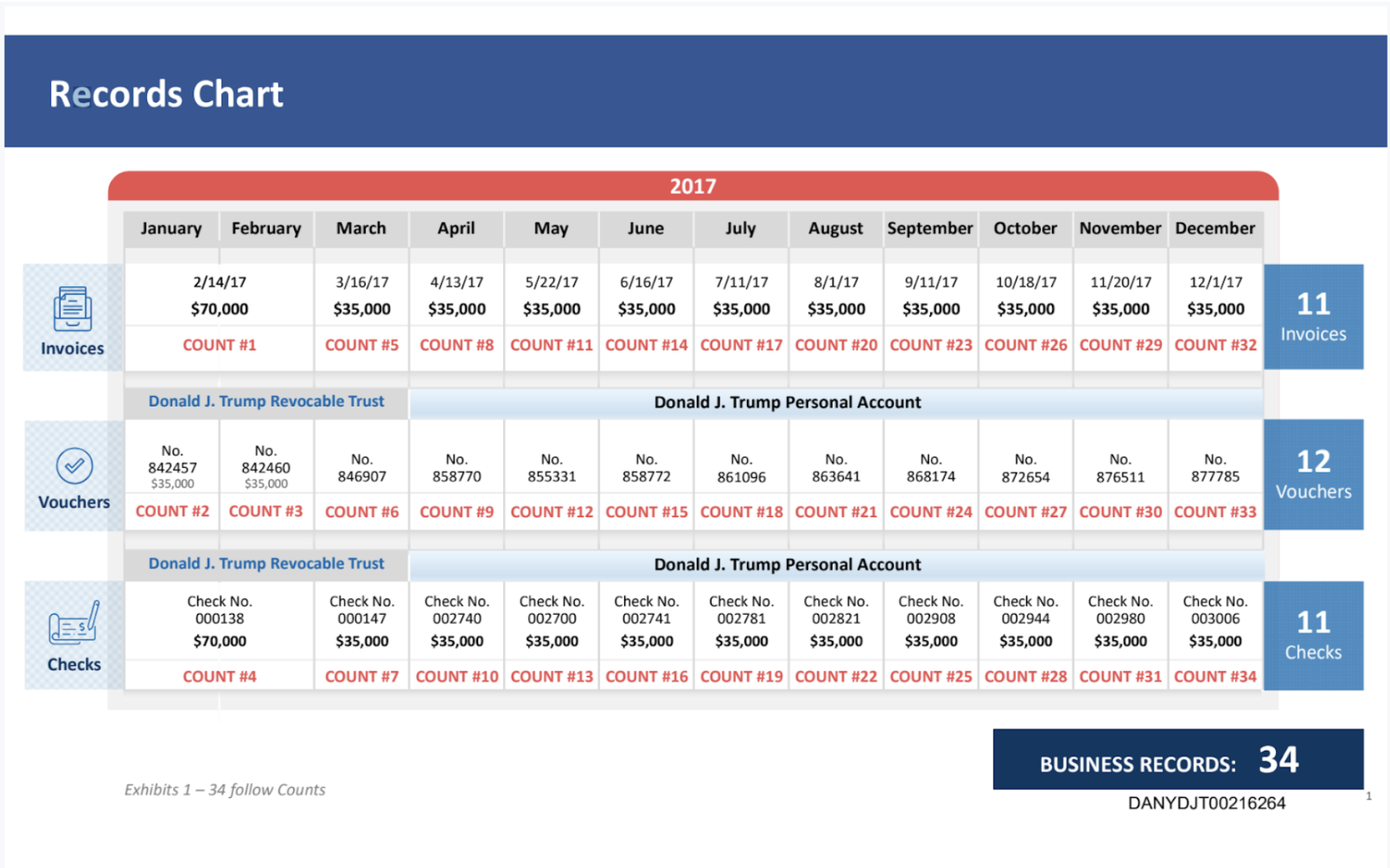

Manochio is a junior bookkeeper at the Trump Organization. She is testifying under compulsion by subpoena. She began working at the Trump Organization in August 2013 as an administrative assistant. She then became an executive assistant, both for Allen Weisselberg and for Jeff McConney.

Manochio begins her testimony speaking softly, and Justice Merchan asks her to speak louder.

As Weisselberg's assistant for eight years, Manochio sat right outside his office, and Weisselberg would interact with Trump every day. Manochio had a role in processing expenses. She put checks together with their backup documentation, and gave them to Weisselberg to sign.

Do you know if Trump's personal expenses were processed by the Trump Organization? Yes.

Do you know how Trump paid his expenses? By check.

Did Trump get a new job in 2017? Yes.

What was that new job, and did he have to move for it? This is apparently not meant as a trick question. He became president of the United States, Manochio says, and he moved to Washington, D.C.

After the drama and strange turns of the morning and Tuesday, it's almost refreshing to be talking about checks and invoices again. As Manochio begins her testimony, one reporter packs up and heads for the door. For him, at least, the show is over.

Manochio recounts how she would prepare and FedEx checks to Washington for Trump to sign. She sent them unsigned and received them back signed.

Recall that most of the Cohen payments came from Trump's account, of which he had the sole signatory authority. Manochio says she would speak to Madeleine Westerhout, Trump's White House executive assistant at the beginning of his term, on the phone when checks were missing or when there was some other confusion.

Mangold displays a FedEx invoice, dated May 29, 2017, an example of the types of FedEx invoices Manochio would regularly see.

We also see a May 23, 2017, FedEx invoice, from Manochio to Keith Schiller (Trump's bodyguard), which is for unsigned checks bound for Trump. Shortly thereafter, we see the tracking ID and shipment date for the return of the package back to Trump Tower in New York. Mangold asks Manochio about exactly how and to whom these packages were sent, delivered, received, and returned.

These are unsigned checks that you sent to Washington, D.C., for Trump to sign? Yes.

Who told you to send the checks? Either Rhona Graff or Allen Weisselberg.

Do you always send checks for Trump to sign by Fed Ex Priority Overnight? Always.

What are the last four digits of the tracking ID? 7364.

In short, he sends the FedEx, she receives the FedEx. The checks go to D.C. unsigned and come back to New York signed. Easy come, easy go. We go through this 11 more times for each of the additional packages of checks.

Lather, rinse, repeat.

Around September 2017, Manochio's White House point of contact changed to John McEntee, who was a personal aide to the president. In an email, he asked Rhona Graff to put him in touch with "Rebecca that works for Mr. Weisleberg [sic]," because he "will need the bosses personal checks mailed to me."

The prosecution is done with questioning, and Justice Merchan dismisses the jury for lunch. Not a minute too soon; caffeine levels among the press corps are running dangerously low.

Before we are dismissed, however, a few more twists in the road. Blanche informs Merchan of three separate applications arising out of Daniels’s testimony: (1) a renewed motion for a mistrial, (2) a renewed motion to preclude the testimony of Karen McDougal, and (3) a more cryptic matter regarding the gag order as it relates to Daniels. Justice Merchan tables the discussion of these applications for later in the afternoon.

* * *

It’s 2:14 p.m., and Trump walks back in, entourage in tow. After everyone takes their seat, Boris Epshteyn stands and turns to the press gallery, handing a stack of color printouts to Kaitlan Collins of CNN. “Can you give that to George when you see him?” Epshteyn asks Collins, who just looks back at him quizzically. "Conway,” Epshteyn mouths, then wheels back around and takes his seat.

Two minutes later, the prosecution enters through the side door.

Once and future witness Georgia Longstreet, paralegal to the prosecution, had arrived a bit earlier with another paralegal to set up a few documents.

Justice Merchan enters and retakes the bench. Manochio retakes the witness stand, and Justice Merchan calls in the jury.

The judge now gives the jurors a scheduling update: We're going to break today around 4:00 p.m., a bit earlier than usual.

Necheles begins the cross. Manochio's aunt works at the Trump Organization as well, the witness says, and she says as well that it's a nice place to work.

Was Trump the only person who could sign his personal checks? That’s correct.

All the checks for all his personal expenses were the ones being FedExed? No business expenses were in those packages? Correct.

Necheles wants to make the point that Trump was uninvolved in running the business once he became president.

You testified that you got return envelopes after a few days? Yes.

These were bills that needed to be paid promptly, so getting them back promptly was important to you? Yes.

Was it the practice for legal expenses to be booked in his personal account ledger? The witness says she doesn’t know.

It was a very quick cross, and there is no redirect. Manochio is already off the stand.

The People’s next witness is Tracy Menzies, from Monmouth County, New Jersey. She’s clearly going to be another records custodian witness.

Menzies works at HarperCollins book publishing, as a senior vice president of production and creative operations. It is her first time ever testifying in a legal proceeding. She's a custodian of records for HarperCollins, which was compelled to testify pursuant to a subpoena.

How involved are authors in the publication of their books? At HarperCollins, authors have a partner, who works with them to approve cover designs and on other publication matters.

There are multiple points authors have input in their books, including content and cover design? Yes, they are very involved.

What about when there's more than one author? Do all of the authors have to sign off on the content? Yes.

Mangold asks her about the book "Think Big, Make It Happen in Business and In Life." We see People's Exhibit 415: It's the cover of "Think Big" with “TRUMP” emblazoned across the top, and a picture of Donald Trump pointing straight at the viewer with his mouth open as if mid-sentence. He wrote the book with a man named Bill Zanker, who is not pictured on the cover and whose name is not scrawled in block letters across the top.

We now see the title page, and Trump's name is just as big as, if not bigger than, the title itself.

"Think Big" was originally published in 2007, but the version we're looking at is from 2021.

In "Think Big," Zanker and Trump have distinct voices, distinguished by different fonts (serif for Trump, non-serif for Zanker) and dedicated sections. From Trump's section, a subhead: “DO NOT TRUST ANYONE.” Trump advises: "Get the best people, and don't trust them."

We see this from page 160: "I value loyalty above everything else—more than brains, more than drive, more than energy."

And this from two pages later: "I think the reason we have so many loyal people is that we reward loyalty, and everybody knows this. It has become part of the corporate culture of The Trump Organization. People like Allen Weisselberg and Matt Calamari are great and have proven themselves over many years."

Another excerpt now, along the obverse theme: disloyalty. "I just can’t stomach the disloyalty. I put the people who are loyal to me on a high pedestal and take care of them very well. I go out of my way for the people who were loyal to me in bad times. This woman was very disloyal, and now I go out of my way to make her life miserable.”

And another: "My motto is: Always get even. When somebody screws you, screw them back in spades."

Mangold has no further questions, and Blanche steps up to cross-examine the sacrificial offering of HarperCollins. Were you part of the publishing of this book? No, I was not.

Is it fair to say that covers of books are designed in part for sales, to help sell the book? Yes, but they're done very closely with the author.

Blanche points out that she was shown only six redacted pages out of more than 300 pages, six pages carefully chosen by the prosecution.

Every page you read was partially redacted, correct? Yes.

And you were shown a portion of six pages of the 380-page book picked by the prosecution? Yes.

Is it fair to say that Trump and Zanker may have had help writing the words that were ultimately published? It’s possible.

He has no further questions. There is no redirect, and the witness steps down.

* * *

"The People call Madeleine Westerhout."

Recall that Westerhout was Trump’s executive assistant at the beginning of his presidential term, and importantly, she was there when Trump met with Cohen at the White House. She is dressed in all white and looks eerily similar to Rebecca Manochio.

Mangold begins her direct examination. Westerhout is now the chief of staff to the chairman of a geopolitical consulting firm. Do you know former President Trump? I do.

She was compelled to appear by subpoena, and this is her first time ever inside a courtroom.

Are you nervous to testify today? I am now, yes, she says laughing, well, nervously.

Westerhout says her counsel "graciously agreed" to take her case pro bono.

She began her career in D.C. at the Republican National Committee, working for the finance director. In 2016, did you become aware of what became known as the "Access Hollywood" tape?

Yes, she says, and she describes it. "At the time, I recall it rattling RNC leadership," she says.

She recalls conversations at the time about how it would be possible to replace Trump as the candidate. After the election, Westerhout says she worked out of Trump Tower, helping the president-elect coordinate Cabinet interviews and other matters, even though she lived full time in D.C. still. Westerhout says she got a nickname in the media—"the greeter girl"—for her role scheduling high-level meetings.

Mangold asks about Rhona Graff, with whom Westerhout worked between the election and inauguration.

"We worked seamlessly together," says Westerhout.

Do you know someone by the name of Michael Cohen? Yes, he was the president's former lawyer.

How do you know him? He was around in Trump Tower.

She testifies: At some point, my boss came to me and said do you have any interest in sitting outside of the Oval Office, Westerhout says, and she thought it would be a cool experience. Titles were not discussed yet, but she said yes.

Westerhout says Trump moved from Trump Tower to the White House on January 20, 2021—Inauguration Day—and she recounts that day, in the West Wing right outside of the Oval Office. She "technically" started her job right then that very day, she says.

Mangold displays a floor plan of the West Wing.

Where is the Oval Office? Um, it's the Oval Office, labeled “Oval Office,” at the bottom.

The room is not hard to distinguish: All the other rooms are square- or rectangle-shaped.

Westerhout says she sat in the "outer Oval Office," and points out on the floor plan where her desk was—it's just about as close as you could get to the Oval Office without being in the Oval Office itself.

Also sitting in the outer Oval Office were Hope Hicks, John McEntee, and Keith Schiller.

Dan Scavino was "one of the president's very trusted advisors"; he did a lot of Trump's communications and his job was to "get tweets out," says Westerhout.

As Trump's special assistant and executive assistant, was the president your only focus? I tried to have it be my only focus, she says with a nervous laugh.

Did you have job training or orientation? Not formally, no. She says she observed Hicks, Scavino, and others to learn.

We progress in time through Westerhout's CV: Eventually she became director of Oval Office operations, and her desk changed with her title.

Did you develop an understanding of Trump's work habits and preferences? I hope so.

His relationships and contacts? Yes.

His social media presence? The way he interacted with his family? Yes and yes.

Concerning his work habits, Westerhout says he preferred speaking with people in person or on the phone. He took "a lot" of phone calls in the day, starting as early as 6:00 a.m. and going on late into the night. There's a "rather complicated process," to call the president, she says. One way is to call Westerhout's desk, and she would patch calls through. But John Smith on the street calling 1-800-WHITEHOUSE wouldn't just be patched right through.

Did Mr. Trump use a computer? Not to my knowledge.

Did Mr. Trump have an email account? Not to my knowledge.

She says Trump liked hard-copy documents, and liked to read; in fact his job in 2017 required quite a lot of reading. Westerhout says Trump wanted to keep the Resolute Desk "pristine," and only for meetings, so he would do a lot of his reading and other work in the "dining room," just off the Oval Office.

Was he organized? To my understanding, the president knew where things were, but he had a lot of papers he would take with him.

Did he have attention to detail? Yes.

What were his signing practices? He worked by hand; he liked to use Sharpies or a Pentel felt tip pen, says Westerhout.

With the exception of the nervous laughter earlier, Westerhout is composed and clear, answering graciously and thoroughly, but never with excess detail.

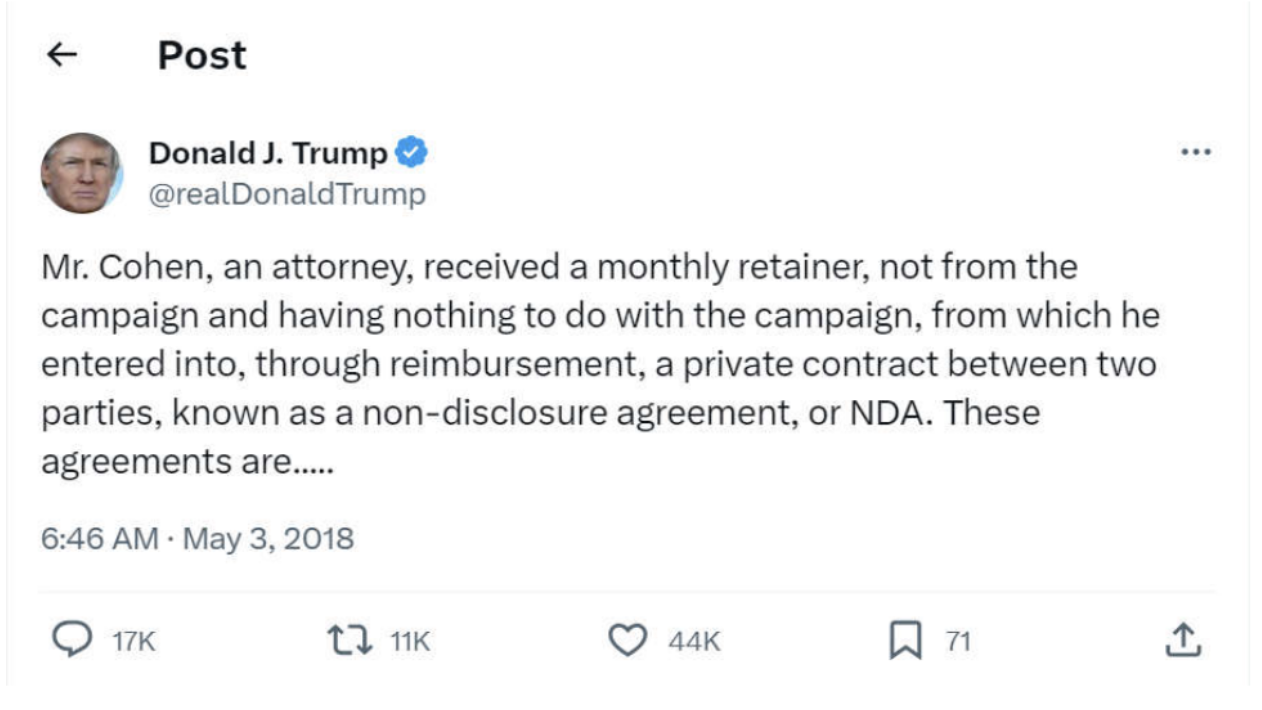

Did anyone else have access to the @realDonaldTrump Twitter account in 2017? Only Dan Scavino and Trump.

Did Scavino ever post a tweet without Trump's approval? The president did like to see the tweets that went out, she says, but she didn't see every tweet they posted and thus doesn’t know for sure what system they had for approval.

Every now and then, Westerhout says, if Scavino wasn’t available, Trump would dictate a tweet to her, which she would scribble down on a piece of paper, type up and then print out (because Trump couldn't read her handwriting). Then he would review and edit the hard copy, sometimes a couple of times.

Westerhout says that there were certain words that Trump liked to capitalize, like "country," and he liked to use exclamation points—a fact that we already knew. "It's my recollection that he liked to use the Oxford Comma," she adds.

Were there things he overlooked during that time? He was attentive to things that were brought to his attention, she says.

Westerhout says she would coordinate with the Trump Organization on occasion. In 2017, her main point of contact was Rhona Graff. Mangold displays a Jan. 20, 2017, email from Westerhout's White House email address to Graff's Trump Organization address with the subject line, "Contacts": “Could you have the girls put together a list for me of people that he frequently spoke to?” Westerhout had asked Graff. Westerhout clarifies that the “girls” in this context are a couple other assistants that worked for the Trump Organization.

We see a reply: “How's this for a start? R.” Graff responded, with an Excel file attachment of contacts for Westerhout.

The email is accepted into evidence, and we see the redacted contact list—friends, family, other people Trump might want to speak to. We see a few of the contacts, including Trump's sister, brother, and daughter, as well as Allen Weisselberg.

In row 41? David Pecker.

"At the time, I knew him to just be a tabloid person," Westerhout says.

In row 13? Michael Cohen.

Did Trump and Cohen have a close relationship in 2017? At that time, yes.

Did he ever visit the White House? Yes.

Mangold now pulls up People's Exhibit 391, a Feb. 5, 2017, email from Westerhout to Cohen. “Subject: Wednesday meeting,” "Michael- We're confirmed for 4:30pm on Wednesday." The email also asks Cohen for some personal identifying information, “What I need from you is the following: full name as it appears on your ID[;] DOB[;] SSN[;] us citizen- y/n[;] Born in the us- y/n[;] Current city and state of residence[.] Thanks! Madeleine.”

Do you recall why you were sending this email? Mr. Cohen was coming in to meet with the president.

Do you recall seeing him when he came to visit? No.

Did this visit, ultimately, occur? Yes.

Mangold moves on, and asks Westerhout whether she remembers David Pecker’s name coming up at all in 2017. Westerhout says she recalls a text she had sent to Hope Hicks in 2017 asking if she had called Pecker.

We see that text exchange, which is People's Exhibit 319 and dates from March 20, 2017. From Westerhout: "Hey- the president wants to know if you called David pecker again?"

Now we see an email from Westerhout to Graff from Jan. 27, 2017, re: Photo. There is an attachment of the front page of the New York Times from that day. It features a photo of Trump saluting a soldier as he boards Air Force One, with the headline “Tax Plan Sows Confusion As Border Tensions Soar.” The email reads: "Can you please send this to Alan Weisselberg from the President? He sent to his family and wanted Alan to see it as well. First time boarding Air Force One!"

Is it common for Trump to send newspaper clips to his family and Weisselberg? Yes

Did Trump and Weisselberg have a close relationship in 2017? I understood them to be close.

Did you pass messages back and forth between Trump and Weisselberg during 2017? I don’t recall other messages besides this one, but it wouldn’t surprise me.

This doesn't strike you as unusual?

An objection is overruled.

Westerhout answers: No.

We see the attachment: the cover of the New York Times with a photo of Trump boarding Air Force One for the first time.

How were Trump's personal expenses handled in 2017? My understanding is that they were handled by checks. They were sent by the Trump Organization to Keith Schiller, then to me, and I brought them to Trump to sign.

She describes the FedEx package and the manila folder. Westerhout says she received unsigned checks from the Trump Organization—maybe twice a month. The number of checks in each package varied, from one to a stack half an inch thick. She says she would sometimes see Trump sign checks in his office, each one by hand. After he signed the checks, Trump would hand the folder back to Westerhout, who would place it in a prelabeled envelope and ship it back to the Trump Organization.

Was there ever a time Trump didn't send back every single check in a packet? I don't recall.

A few times, Westerhout remembers that Trump would call Weisselberg or someone else at the Trump Organization to ask for clarification about a check.

We now see People's Exhibit 73—an April 6, 2017, email from Graff to Westerhout: "M: Here is the FedEx label you requested. Hope it works ;)" We see the FedEx label, which apparently worked (winky face), and Mangold displays another exhibit, People's Exhibit 76, in which Westerhout had emailed Graff: "R- can you have someone send me a fedex label to send back the checks the President just signed?"

We're flying through exhibits, now People's Exhibit 71, another email from Westerhout, from Feb. 21, 2017, bearing the subject line, “Re: Winged Foot Golf Club.” It reads: “Rhona- can you help me with this? See attached. Thanks! Let me know if I should call them directly." The attachment is an invoice for Trump's dues to a golf course. Graff had written on the invoice asking whether Trump would like to suspend his membership for the next four-to-eight years, or continue to pay his annual dues. "PAY" Trump wrote. And at the bottom: "ASAP" with his shortened signature.

It's not quite clear what his golf club invoice has to do with anything, but we continue plowing through exhibits anyway.

Next is an email about a photograph Trump wanted framed to display behind his desk in a credenza. Graff says she doesn't have a frame on hand, but she can pop over to Tiffany's to get one, though the frames there are on the pricey side.

A reporter in the gallery yawns. This must be some of the most mundane correspondence for an early-term presidency in U.S. history.

Do you remember Trump's reaction to a story about him and Stormy Daniels in early 2018? I remember he was very upset.

Did he talk to Cohen around that time? I believe so, yes.

How would you describe Trump and Melania's relationship? It was one of mutual respect. He cared about her opinion, and there was no one else who could put him in his place. He was my boss, but she was in charge. Their relationship was really special. They laughed a lot.

Did Trump's relationship with Melania change when the Stormy Daniels story came out? Not to my knowledge, no.

And at some point did you leave your job at the White House? Yes.

Mangold asks her about the circumstances of her departure. Westerhout begins to break down.

She explains that in August 2019, she was invited by a White House colleague to what she understood to be an off-the-record dinner. “And at that dinner I said some things that I should not have said,” Westerhout explains tearfully, “That mistake, eventually—ultimately cost me my job. And I am very regretful of my youthful indiscretion.”

She wipes her tears. She seems genuinely regretful about the whole episode. (For context, Westerhout was reportedly fired for making inappropriate comments about Ivanka and Tiffany Trump at said dinner.) She wrote a book about it, she says, her voice shaky and faltering, and we see the cover now displayed: “Off the Record: My Dream Job at the White House, How I Lost It, and What I Learned.” She thought it was important to share with the American people the man that I got to know. I don't think he was treated fairly, and I wanted to tell that story she says, through more tears.

Since publication, Westerhout says she spoke to Trump at a fundraiser in Orange County, but says that she did not discuss this case.

No further questions from Mangold.

Before she walks up to the lectern, Necheles asks whether Westerhout would like a break.

No break, Justice Merchan says, but we're going to stop at 4:00 o'clock.

You were very young, and you made a mistake? Yes.

You thought he was great to work for, and a great president? Yes, she says, more tears.

Back to the 2016 nomination, the transition, and the "Access Hollywood" tape. You testified that it rattled the RNC leadership, and there were a couple days of consternation, but that happened all the time? Yes.

When Trump was running, there was always some event when—Necheles claps her hands and wipes them clean—there was total consternation.

She is familiar, friendly with Westerhout. Much friendlier than she was with Daniels.

Necheles reminds Westerhout of Trump's apology for "locker talk," and that he said he would see everyone at debates and Westerhout laughs, as if she remembers it fondly.

The "Access Hollywood" tape "blew over in a couple days," and after that Trump won the election right? Yes. The clock is ticking. We have nine minutes left according to Justice Merchan, and Justice Merchan is always on time.

Necheles talks fast, getting more questions in. It was a busy time? Yes.

You were called "the greeter girl," correct? Yes.

Wasn't it a little belittling? Yeah. I tried not to let it get to me, but people said I was unqualified, Westerhout says about the "greeter girl" nickname.

Trump was also transitioning his companies into a trust, Necheles asks, but Westerhout says, she doesn't know anything about that. She wasn't involved in the business side.

Westerhout says Trump only had two and a half months to transition from running the Trump Organization to becoming president. Necheles keeps portraying it as a hectic, busy time, with lots of distractions. It was amazing working with Trump, Westerhout says, smiling. I don't know if anyone should feel like they deserve to be in the West Wing, but Trump always made me feel like I belonged, especially in a place with a lot of older men.

We now get a portrait of Trump, the family man.

He had a close relationship with his children, and a lovely relationship with his wife? Yes, definitely, Westerhout says.

Westerhout paints a touching scene: Trump would be on the phone with his wife and would tell her to come to the window in the residence, where she could look across and see Trump in the Oval Office. He would also call his wife to tell her he's boarding Air Force One, though he didn't have to.

And right on schedule, Justice Merchan stops it there.

We end with an image of Trump the family man from Westerhout's testimony, which couldn't be further from this morning's depiction of Trump the philanderer and sexual bully of Daniels's testimony.

Justice Merchan gives his pro forma instructions to the jury and sends them home. He then declares that we’ll take a 10-minute break and then pick things up with arguments. As Trump walks out, a member of the public says to Trump, “God is with you. Stay strong.”

"Guys, we're not doing that," a court officer immediately snaps at them. After the parties leave, the officer points to the man who spoke to Trump and then to the door. “You too,” he says to the man’s seat partner, and takes them both out the back door of the courtroom.

* * *

At 4:09 p.m., Trump and co. walk back in, and Justice Merchan walks back in as well, almost simultaneously. Remember, counsel has gathered to discuss three separate applications: a renewed motion for a mistrial, a renewed motion to preclude Karen McDougal’s testimony, and Trump’s gag order as it relates to Daniels.

Blanche cheerfully announces that the People have informed him that the prosecution no longer intends to call McDougal to testify. So scratch that from the list.

But we still have two issues to cover. The first is the gag order.

Blanche asks that Trump be allowed to respond publicly to Daniels's testimony, because of all the reporting about it. This reporting tells a completely different story from Trump's. This will tie into the mistrial motion, he says.

Daniels was on a political TV show with "political commentators" last night, Blanche says, and Trump can't even say this never happened to this "new version of events." This new story deals with a very different issue than the mere alleged sexual event that took place in 2006. We said repeatedly, and I'm not going to dwell on it, Blanche says, but Trump needs an opportunity to respond to the American people.

The only witness left subject to the gag order is Mr. Cohen, Blanche says, arguing that Justice Merchan’s concern about the gag order should “give way to the testimony of the past couple of days.” There are voters out there, asking questions, but Trump can't say anything, Blanche says. There are numerous articles about it in the news, and Daniels's testimony will be a feature on shows today, and it "cannot be" that he can't respond to it, says Blanche. It's much different than the same story that's been going around for several years, so Blanche asks that Trump be released from the gag order.

Christopher Conroy is up now to respond for the prosecution: It seems the other side lives in almost an alternate reality, he says. Conroy wants to look back at why the order was an issue in the first place, and says that it has been somewhat successful thus far.

This is where facts are brought out, and if someone wants to respond to something someone said in this room, it should happen in this room, not out there, Conroy says.

We have been told repeatedly by witnesses—even in the courtroom, even on the stand—about their fear, Conroy says. Even with a witness today, there was something with her home address on it, and you could see the fear in her eyes. Trump talks about witnesses selfishly with no concern about the safety of the people he's attacking, and unfortunately we have seen the results, Conroy says. Conroy brings up the NYPD's explosion in threat cases involving members of the district attorney's office and their families. I had a conversation with a custodial witness last night concerned about safety, Conroy says. Modifying this gag order now in the middle of trial would signal to future witnesses that they could be at risk as well.

He cites a D.C. Circuit case about "hostile messages" that have an effect of "deterring, chilling, or altering the involvement" of witnesses. The gag order is not just designed to protect the witness until he or she walks off the stand, or to protect the proceedings part of the way, Conroy says.

Modifying the gag order now would be calculated to allow Trump to attack Daniels—that's what he wants to do. Let's not pretend he wants to engage in high-minded discourse, Conroy says.

Blanche is back now, and he says everything we just heard is different in kind from what they're requesting.

In this case, a narrowly tailored gag order, the court should be constantly making sure its terms remain in effect, Blanche says.

A completely different set of events, Justice Merchan repeats? What exactly are you referring to?

For example, transcript page 2610, Blanche cites:

At first I was just startled. Like jump scared. I wasn’t expecting someone to be there. He’s essentially, minus a lot of clothing. That’s when I had this moment where I felt the room spin in slow motion. I felt the blood basically leaving my hands and my feet and almost like if you stand up too fast, and everything just spins. That happened it too. Then I just thought, oh, my God, what did I misread to get here? Because the intention was pretty clear.

What she had previously said, Blanche says, hinting that he's now getting to the mistrial motion, was "ugh, here we go, we started kissing, I hope he doesn't try to pay me."

Reponds Justice Merchan: Help me understand how it's different.

One is about consent, says Blanche, and one is not.

Justice Merchan wants to take the issues one-by-one, so we stay on the gag order.

My concern is protecting the integrity of these proceedings as a whole, he continues, “That means everybody sees what happens.”

Other witnesses, including but not only Michael Cohen, will see your client doing whatever he intends to do, Justice Merchan says to Blanche. I can't take your word for it that this is going to be low key, that this is going to be a response, because that's not the track record.

These were very real, very threatening attacks on witnesses, so I can't take your word for it, Justice Merchan says, while saying he is still concerned by some witnesses using the gag order as a sword, not a shield.

The application to modify the gag order is denied.

The judge will now hear the defense’s renewed motion for a mistrial.

Blanche starts by saying he will put something together over the weekend explaining why this trial cannot go forward in light of Daniels's testimony. Blanche cites Justice Merchan's finding that Daniels's testimony not only completes the narrative of events but is also probative of the defendant's intent, but says he alerted the court and the government of Daniels's contradicting previous claims.

Blanche says this new story is about how "this completely made-up encounter with President Trump may have been nonconsensual," which the defense learned from the documentary, to which the defense previously objected. The prosecution and the court promised not to get into the details, but then they did.

He moves on to questions about whether the encounter brought up Daniels's difficult childhood—and Daniels spanking Trump. It almost defies belief that we're here about a records case and the government is asking questions about an incident that happened in 2006, that we don't even believe happened.

Blanche continues, This is extremely prejudicial testimony. This is not a case about sex. This is not about whether that encounter took place or didn't take place. Whether it happened or not has nothing to do with the charges in this case. Blanche reads more of Daniels's testimony, calling it "extremely prejudicial" again, and testimony that has nothing to do with the motive of entering the NDA.

We didn't know these questions were coming, Blanche continues. We had a sense from the documentary that she was changing her story, and we alerted the court, but we were hearing this for the first time.

"There was an objection, and it was sustained," Justice Merchan cuts in. "In fact, after many of these anecdotes, there was an objection and it was sustained."

But it was still said, Blanche pleads, that's why this testimony is so dangerous, so prejudicial.

"It was so prejudicial—it was a dog whistle for rape," Blanche says.

Let's hear from the People, the judge says.

"Ok so that was a lot, and most of it, just flat out untrue," says Joshua Steinglass for the prosecution.

The claim of ambush is just nonsense, says Steinglass. The claim of changing the story is also extraordinarily untrue. As with any witness telling a story at different times and in different contexts, there are details that appear in one form and not in another form. And anyway, the defense has had access to all of this.

Moving on to the mistrial motion, Steinglass says, it has always been the prosecution’s contention that the details of the two-hour conversation that Daniels and Trump had in the hotel suite corroborate her account as to the fact that the sex happened (which increases motivation to silence her in 2016).

These are the details that make her account more credible, and the defense has gone to great length to discredit her, Steinglass says with some force, some oomph in his voice.

They're trying to have their cake and eat it too. They're trying to discredit Daniels by arguing that her story is false and then preclude the prosecution from eliciting the details that would corroborate her story, Steinglass says.

Necheles was cherry-picking the details she thought were inconsistent and omitting the details that were consistent, Steinglass says. The overarching point here is the details are the tools the jury needs to assess her credibility.

Those messy details were Trump's motive to silence this woman in 2016, less than a month before the election, says Steinglass. The fact that the testimony is prejudicial and messy, according to Blanche, that's exactly why Trump tried to prevent the American people from hearing it.

There were lots of details about a lot of things, but not about the actual encounter. By Steinglass’s counts, there were only eight questions about it. There are other details I don't want to put on the record, but I'm happy to put in a sealed record the very salacious details we omitted out of a desire not to embarrass the defendant, Steinglass says.

"Please have a seat so I can render my decision," Justice Merchan says to Blanche, who had stood up to argue.

Justice Merchan says he went back to his previous decisions side-by-side with the transcript to make sure that everyone had followed his guidelines.

Your denial puts the jury in a decision of choosing who they believe: Donald Trump or Stormy Daniels. The prosecution doesn't have to prove that a sexual encounter occurred, but they do have the right to try to rehabilitate Daniels's credibility, which was immediately attacked in Blanche’s opening statement. And “the more specificity Ms. Daniels can provide about the encounter, the more the jury can weigh to determine whether the encounter did occur and, if so, whether they choose to credit Ms. Daniels's story.”

Justice Merchan says he objected sua sponte to the trailer park comment and struck it from the record. Following the court's own objection, Justice Merchan notes, Necheles began to object with some frequency, and virtually all of her objections were sustained. “Yet for some unexplained reason, which I still don't understand, there was no objection to certain testimony, which was later used in the motion for a mistrial on Tuesday, and again used today.”

For example, concerning Trump’s non-use of a condom, I “wished those questions hadn't been asked, and I wished those answers hadn't been given. But for the life of me, I don't know why Ms. Necheles didn't object. She had just made about ten objections, most of which were sustained. Why on Earth she wouldn't object to the mention of a condom?”

On the blacking-out comment and the implications of coercion, Justice Merchan says, he actually sustained an objection when it first came up and the witness backtracked and made clear there was no coercion. But for some reason, I don't know why, you went into it ad nauseam on cross-examination, Justice Merchan says, drilling it into the jury's ears over and over.