Stormy Daniels Takes the Stand

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Previously on Trump New York Trial Dispatch: "Fireworks and Waterworks: Davidson and Hicks on the Stand"

May 6, 2024

It's 9:23 a.m., and Donald J. Trump has taken his seat at the defense table. It's a red tie day today. It’s also a radiantly blue suit day.

Trump is flanked by Todd Blanche, who has an arm around the former president as he whispers something into his ear, his hand cupped in front of his mouth. Co-counsels Emil Bove and Susan Necheles stand nearby, unpacking documents onto the defense table.

Across the aisle, the prosecutors install themselves. From right to left, facing the judge, we have Susan Hoffinger, Matthew Colangelo, and Joshua Steinglass. Christopher Conroy sits just behind them.

In the defendant’s friends and family row, Boris Epshteyn is here again. He strolled in a few minutes after Trump.

The clock strikes 9:28 a.m., and our ever-punctual Justice Juan Merchan sweeps in, resplendent in his robes, judicial authority radiating from his very being. All rise as he does so, for so the crowd is instructed.

In the press overflow room, a high schooler—here as part of a school field trip to the trial—stands as well. He quickly sits down again when he realizes no one else in the press room has joined him. Being the only person in a courtroom who stands for a judge on a television monitor because someone in a different courtroom calls out “All Rise!” is the kind of thing that traumatizes high school students. It’s the kind of emotional injury from which not everyone recovers. This student has all of our thoughts and prayers.

Speaking of radiating judicial authority, Justice Merchan has some judicial authority he wants to radiate.

He says he wants to address the defense and Trump himself. The prosecution has filed three separate motions to hold Trump in contempt for serial violations of Justice Merchan’s gag order. Justice Merchan says he is about to issue an order holding that Trump has, for the 10th time, violated the order. "It appears that the $1,000 fines are not serving as a deterrent,” he says. “Therefore, going forward this court will have to consider a jail sanction" for future violations.

It's the last thing I want to do to put you in jail, he says. There are many reasons why incarceration is truly the last resort. It will obstruct the proceedings, Justice Merchan says, which is the last thing that he imagines Trump wants—considering that the candidate presumably wants to get back out on the campaign trail.

But at the end of the day I have a job to do, the judge says. Your continued willful violations constitute a direct attack on the rule of law. I cannot allow that to continue. As much as I've wanted to avoid a jail sentence, I will as necessary and if appropriate impose one, he says.

Justice Merchan hands down his decision, to the defense and prosecution. Trump looks at it silently.

The order details Trump’s alleged violations of the gag order on four separate occasions: (1) in an April 22 statement made to media outside of the courtroom in which Trump accuses Michael Cohen of lying; (2) in an April 22 interview in which Trump said the jury was composed of “95% Democrats”; (3) in an April 23 interview in which Trump referred to Cohen as a “convicted liar”; and (4) at an April 25 press event in which he referred to David Pecker as a “nice guy.” Justice Merchan holds Trump in contempt on the second of these counts and not on the others.

The last page of the document features the headline “PUNISHMENT AND ORDER” and commands Trump to pay another $1,000 fine for his violation of the gag order. But like Merchan’s warning to Trump in the courtroom, the decision cautions Trump of jail time in the future if he does not mend his ways.

The order reads, “However, because this is now the tenth time that this Court has found Defendant in criminal contempt, spanning three separate motions, it is apparent that monetary fines have not, and will not, suffice to deter Defendant from violating this Court’s lawful orders.” It continues, “Therefore, Defendant is hereby put on notice that if appropriate and warranted, future violations of its lawful orders will be punishable by incarceration.”

And with that, the clerk calls the trial. “This is People of the State of New York against Donald J. Trump, Indictment 71543/23. Case on trial continued.”

Emil Bove rises now and says he wants to raise some objections to exhibits that will be introduced today, and he asks to do so outside the presence of the jury. If the court is willing to go through them one by one beforehand, that would be great.

Justice Merchan is annoyed. Why would you ask for this only now—with the jury already waiting? Why wasn’t this raised earlier so I could look at these exhibits over the weekend? And how many exhibits are we talking about, anyway?

There are 26 such exhibits, prosecutor Matthew Colangelo says. He’s exasperated too. The defense has known about today’s witness and these exhibits for weeks, he says. And we're arguing only this morning about the evidence that the prosecution intends to introduce during Jeff McConney's testimony today. McConney was the Trump Organization's controller until his retirement last year.

Bove protests that it's very hard for him to object to the exhibits on the fly; I still don't know what the exhibits are, Bove protests.

Justice Merchan asks, why can’t we do it at a sidebar? Bove says that he thinks it would be more orderly to take these one by one, but the judge doesn't want to keep the jury waiting.

I’m just trying to make sure I have the opportunity to object and be heard on this, Bove says. You'll have an opportunity, Merchan promises. But we’ll do it in sidebars, not in a dedicated hearing which will eat up the morning while the jury sits and waits.

And with that, the judge calls in the jury, and the People call Jeffrey McConney.

* * *

McConney takes the oath and then takes his seat. He has a mop of white hair, a white goatee, and he wears a dark suit with a blue patterned tie. Assistant District Attorney Colangelo steps up for the prosecution and asks about McConney's education.

He's a Baruch College graduate. He started at the Trump Organization as assistant controller in 1987 and climbed the ranks to become senior vice president and controller in the span of 36 or 37 years.

He also did some tax return work outside the Trump Organization during that time, and he still does some—even in his retirement. McConney is here in response to a subpoena, and the Trump Organization is paying for his attorneys.

When asked his definition of the Trump Organization, McConney says: To me there's two definitions—there are two legal entities, the Trump Organization, Inc. and Trump Organization, LLC. Most people refer to the Trump Organization as President Trump's global holdings and assets—hotels, golf courses, and licensing.

Have you had any contact with Trump since you retired last February? No, McConney says, somewhat sadly. He hasn’t.

Before he retired, he says, more than 500 separate “entities comprised the Trump Organization.” And for those 500 or so entities, what kind of businesses are they in? Golf courses, real estate, licensing deals—that's the bulk of it, McConney says. McConney says that the Trump Organization itself doesn't hold assets. Rather, he says, we've set everything up such that each asset is owned by a separate entity, sometimes multiple entities. But the ultimate owner is the revocable trust, with Trump as beneficiary, McConney says. Donald Trump Jr. and Allen Weisselberg were the trustees of the trust, which was created when Trump became president to hold his business so that he could focus on running the country.

McConney is now discussing his roles and responsibilities as controller. He oversaw the accounting department and general ledger, including accounts payable and processing expense reimbursements. McConney was promoted to controller when Weisselberg was promoted to chief financial officer. Weisselberg was his boss for more than three decades. He also oversaw the accounts payable department. And he was responsible for the general ledgers of each of the components; golf courses and hotels were excluded—they had their own accounting staff, says McConney. But generally, each “entity” within the Trump Organization that had a bank account had a general ledger.

And as controller, it was McConney's job to keep the ledgers accurate. The ledgers were run on a computer program which, early in his tenure at the Trump Organization, it had been one of his first jobs to set up. The current accounting system had been running since 1990 or 1991 and was still going the day McConney retired.

Importantly, McConney says that his accounting staff maintained not only the general ledger of the Trump Organization but also those for Trump's personal bank accounts, including his checking accounts. This is important because some of the checks sent to reimburse Cohen were sent from the trust, while some were sent from Trump’s personal accounts.

Who had signature authority on the DJT account, referring to the initials by which this account was known internally? Only Trump himself, says McConney.

And who had signature authority for the trust account? For amounts less than $10,000 any of Eric Trump, Donald Trump Jr., or Allen Weisselberg could sign. For amounts over $10,000, two or more had to co-sign.

Colangelo now hands up a thumb drive of exhibits, which include documents concerning the general ledger of the DJT account and the trust account, emails for payment approvals, notes for payments, 1099s, and other stuff. McConney confirms that he has reviewed the documents on the drive.

Bove stands and objects to some of the exhibits and is overruled.

"Are you familiar with someone named Michael Cohen?" Colangelo asks McConney, who says he is.

How long have you known him? "I was there as long as he was," McConney says, so maybe five to 10 years. Sometimes we would chat by the coffee machine.

"What was Cohen's position in the Trump Organization?" Colangelo asks.

"Uh, he said he was a lawyer," McConney says, getting the first laugh of an otherwise stiff day.

And did there come a time, Colangelo asks, at which you become aware he was owed money?

We have arrived at the reason for McConney’s presence here today.

Yes, he says. McConney learned this from Weisselberg.

All of a sudden, the day is no longer boring.

According to McConney, Weisselberg said that we had to get some money to Cohen. He tossed a pen towards me and said to start taking notes on what he said, McConney says. The prosecutor shows the People’s Exhibit 35 to him.

The document is a bank record with handwritten notations on it—by two different people. The handwriting on the left-hand side of the page McConney recognizes as Weisselberg’s. How do you know his handwriting? I’ve seen that handwriting for 35 years, he says. The writing reflects various calculations of moneys owed Cohen that add up to a total amount to be repaid in monthly intervals over the course of the 2017 year.

McConney says he cannot identify the handwriting on the right side of the page. He kept this document in a book in a locked drawer in his office, he says.

People's Exhibit 36 is similar to the previous one, and it was apparently stapled to Exhibit 35. Justice Merchan accepts both into evidence.

The first of these two documents is now displayed on the monitors. It's a First Republic Bank account statement for Essential Consulting LLC, the company Cohen used to pay Stormy Daniels. It reflects the $130,000 transfer to Keith Davidson for Daniels, a $35 transfer fee, and the handwritten calculations of Weisselberg that according to McConney reflect that the total amount transferred should be repaid in monthly intervals.

Weisselberg’s written calculations include a few distinct components:

- A $180,000 reimbursement to Cohen, which includes, in turn, a $130,000 wire transfer and a $50,000 payment to a company called Red Finch for technology services.

- A “gross up” or doubling of this figure to $360,000 in order to offset income taxes—a clarification Bove moves to strike but is overruled.

- An additional bonus of $60,000.

McConney explains this latter component, saying that Cohen complained at the time that his bonus wasn't large enough from the prior year; the additional bonus was meant to make up for that.

People's Exhibit 36 is a handwritten note on TRUMP stationery. These are McConney’s own notes on the conversation in which Weisselberg told him that the Trump Organization owed Cohen money. They are more or less consistent with Weisselberg’s notes, though there are some differences.

According to the note, Weisselberg had instructed McConney to wire funds to Cohen monthly from “DJT”—which meant from Trump’s personal bank account—after he came off the payroll “thru Jan 27th 2017.” Below the personal reminder are some calculations, consistent with Weisselberg’s, that come out to $420,000, which when divided by 12 into monthly payments produced payments of $35,000. At the bottom of the note, he specifies to “start $35,000/month Jan. 2017.”

Colangelo asks how much the Trump Organization normally reimburses people for a $100 expense. Normally, employees get $100 reimbursements for a $100 expense, McConney says.

But in this case, Cohen got $360,000 back on a $180,000 expense, right? Correct.

And can you identify any other instance in which an expense reimbursement was doubled to account for tax purposes? No, says McConney.

McConney wrote at the bottom of the note: "Mike to invoice us," as it was typical, he says, for employees to invoice the Trump Organization for expense reimbursements.

Next, we see a Feb. 6, 2017, email from McConney to Cohen: "Just a reminder to get me the invoices you spoke to Allen about." The subject line simply reads, "$$." McConney clarifies that this email referred to the invoices he spoke to Weisselberg about in the last exhibit.

The next email is from a week later, dated Feb. 14, 2017, from McConney to Cohen. It says: "Please send me invoices so I can have the checks cut." Cohen responded about an hour later: "Jeff, please remind me of the monthly amount." McConney responded: $35,000 per month.

Cohen responded with a crude invoice covering January and February: "Dear Allen, pursuant to the retainer agreement kindly remit payment for services rendered for the months of January and February, 2017."

While the email refers to “the retainer agreement,” McConney testifies that he never saw a retainer agreement.

In an email to McConney dated Feb. 14, 2017, Weisselberg approved payment for Cohen's invoice, “as per agreement,” McConney says. McConney then wrote to Deborah Tarasoff: “Please pay from the Trust,” meaning the Donald J. Trump Revocable Trust, “Post to legal expenses. Put ‘retainer for the months of January and February 2017’ in the description.”

Colangelo asks why the payment was made by the trust and not by the DJT personal account. At the time, says McConney, we were paying Trump's personal expenses through the trust account.

McConney is now discussing how this expense was translated onto the general ledger, after which outside accountants would have access to some of the information.

This conversation is now repeated, in essence, 10 more times—once more for each remaining month of the year. They go through the email exchanges authorizing payment for March.

Before turning to April, however, they do a brief but important detour. Did there come a time when they switched from the trust account to the DJT account? Yes.

And on this account, Trump was the only signatory, right? Yes.

And where was he located? Washington, D.C.

So when you switched, what did that mean? They had to get checks to the White House in order to get Trump’s signature.

Some details change over the course of the year. For example, we take a step back at one point because the April 2017 check was apparently lost. We thus see another email: "Please pay June and put a stop on the 4/13/17 ck cut out of DJT and replace it." At some point in the year, moreover, the correspondence no longer reflects the specific amount to be paid, $35,000 per month. But McConney says he understood the amount to still be $35,000 based on prior invoices and the notes he took in Weisselberg's office at the beginning of the year. And the basic pattern stays the same as we continue to follow the monthly payments processed by the Trump Organization's accounting staff—from invoice to internal approval to payment to ledger. With each set of materials, Bove continues to make the same objections, and Justice Merchan continues to overrule them.

Lather, rinse, repeat—for the whole year.

The payments ceased after the December 2017 invoice, and Justice Merchan suggests it’s a good time for our morning recess.

* * *

When the break is over, we turn to People's Exhibit 45, which is an accounting report run for a specific vendor for the period January 2017-January 2018. The vendor for this report is Michael Cohen.

McConney says he doesn't know who printed this document, but he says it contains Tarasoff's handwriting, and he assumes she generated it. The handwriting lumps three payments together and writes $105,000—summing up the funds paid out from the trust account.

The remaining payments are grouped together and the handwriting notes that they total, $315,000. They "were cut from the president's [Trump's] personal banking account," McConney says.

Colangelo now walks McConney through a series of financial reports from the Trump Organization’s accounting system. The first is a detail general ledger report from the Trump revocable trust for 2018. A few pages of the document show legal expenses.

Were any payments in 2018 to Cohen billed as legal expense? No.

The next is detail general ledger report, also for calendar year 2018, but this one for Trump's personal account. On this one there are lots of legal expenses. Do any of these reflect payments to Cohen for legal expenses? No.

The next document is another detail general ledger for the trust account for calendar years 2017 and 2018. It shows the three payments to Cohen from the trust account between January and March 2017, coded as a legal expense and totaling $105,000. And there’s another detail general ledger for Trump's personal account, for the same period. This one shows legal expenses paid between April and December 2017; there's a description of a retainer in connection with each payment; the payments total $315,000.

Colangelo and McConney now turn to the Trump Organization’s IRS form 1099s for 2017. The first is the Trump trust’s 1099-MISC for Cohen. It reflects non-employee compensation of $105,000. The second is a 1099-MISC, with the payer as Donald J. Trump personally, which lists non-employee compensation of $315,000.

Are you familiar with the Office of Government Ethics? Colangelo asks McConney, getting a few subdued chuckles from the gallery. McConney, however, does not seem to find the question amusing. He is familiar with OGE, and also with its required form 278E—a financial disclosure and conflicts of interest form that Trump had to file annually and which was prepared in large measure by accounting staff at the Trump Organization.

What kind of info has to be disclosed? There’s a schedule of all the entities Trump owned, a listing of assets and their value, location, and the income they generate, his retirement funds and payments, his spouse's accounts, his stock and bank account holdings, his liabilities, and gifts he received.

Preparing the 278E form was a heavy lift, and McConney had to do it for each year McConney was at the Trump Organization and Trump was a public official. McConney says he would work until 4:00 a.m. filling out these documents. That "might be normal for you," he says to Colangelo—who does seem to be the hard-working type—but it is "not normal for my life."

The prosecution offers Trump's 2017 report into evidence, Bove objects; there’s a sidebar, and Justice Merchan overrules the objection.

We see People’s Exhibit 81: Trump's annual conflict of interests form for 2017. It's signed by Trump himself and dated May 15, 2018.

Colangelo draws the witness’s attention to page 45 of the document, where there is Part 8: Liabilities. McConney reads: “In the interest of transparency, while not required to be disclosed as ‘reportable liabilities’ on Part 8, in 2016 expenses were incurred by one of Donald J. Trump’s attorneys, Michael Cohen. Mr. Cohen sought reimbursement of those expenses and Mr. Trump fully reimbursed Mr. Cohen in 2017. The category of value would be $100,001-$250,00 and the interest rate would be zero.”

It is 12:16 p.m., and Colangelo has no further questions.

"Your witness," Justice Merchan says to the defense.

* * *

Emil Bove gathers his binder and steps up to the podium. After a brief introduction, he dives into questioning. At the time of these reimbursements you just testified about, in 2017, Michael Cohen was a lawyer, correct?

McConney’s response is unexpected and gets a respectable laugh from the gallery. “Okay.”

Bove pushes, “Right?”

“Sure, yes,” says McConney.

Once again, it’s the tried and true Cohen punchline. Everyone hates the guy.

Bove, however, does not get sidetracked.

Payments to lawyers are for legal expenses, right? Yes

And you booked those expenses as legal expenses, right? Yes.

You rarely had conversations with President Trump, right? Very rarely.

And you never gave him a tour of the accounting system, did you? Right.

Did Weisselberg ever suggest that Trump told him to do these things? No, McConney says. He never told him that.

McConney says he never talked to Cohen about these issues in 2017, despite these emails.

During Cohen's years at the Trump Organization, your interactions with him were not frequent, right? "Minimal," responds McConney.

Cohen worked as the "personal attorney" of Trump, "outside the Trump Organization," Bove asks. McConney confirms this.

Bove shows McConney correspondence from Cohen. He focuses on Cohen’s signature block. It says Personal attorney to Donald Trump; it doesn't say "fixer," right? Right.

And he's not using a Trump Organization email account, right? Right. It's a Gmail account–i.e., personal.

So Cohen was akin to a vendor to Trump? Right.

And you don’t actually know one way or another, Bove says, whether he did legal work for Trump in 2017? That's correct.

Or whether he did legal work for Trump's family?

An objection from the prosecution is sustained.

Bove asks if McConney previously testified that Jan 2017 was a period of "flux and chaos" at the Trump Organization.

"That's putting it mildly," McConney says.

We continue to discuss the trust: There were two trustees—one of Trump's sons and Weisselberg—and there were 500 entities with thousands of employees rolled up into it. There are hotels with guests in the thousands, and golf courses with members in the thousands. As a result of this diversity, there was a very real commercial risk, and the organization was paying marketing people to manage that risk, right? McConney says he is not “a marketing person,” so it is difficult for him to answer the question regarding commercial risk, but he did understand that the organization was paying marketing people.

Bove gets McConney to reiterate that each one of these entities with a bank account had a general ledger. The general ledger for Trump was "like his personal checkbook," according to McConney.

So that could include utility bills? Yes.

Educational expenses for children? Yes.

And this was part of his separate general ledger? Yes.

McConney had testified previously that he oversaw Trump's individual cash position. Bove now asks him about Trump’s cash holdings.

There were times during the course of your employment where his cash position was in the hundreds of millions of dollars, right? Yes.

McConney also confirms there were times in 2017 when Trump had at least $60 million in unrestricted cash.

Bove displays People’s Exhibit 36 once again—the document with McConney's notes on Trump stationery he took in a meeting with Weisselberg. He wants to talk specifically about the line "x2 for taxes."

McConney confirms that Weisselberg had a lot of experience but he wasn't a tax accountant. And under questioning from Bove, he admits that he doesn't know exactly what Weisselberg meant by "grossed up," nor does he know how Cohen treated these payments on his own taxes, nor does he know anything about "Red Finch for tech services."

Bove is keen to highlight the many things McConney doesn't know, as each of these things could feature in a closing argument about how the Trump Organization bureaucracy wasn’t ordered by Trump to cover up or to disguise the reimbursement. It just did what it did—and certainly not at Trump’s direction.

Isn’t it true that McConney kept his notes and Weisselberg’s in a locked cabinet in his office because the payroll books in the cabinet contained personal identifying information relating to employees—not because these notes themselves were sensitive? Correct, McConney says, who goes on to say that most of the drawers in his office were locked for the same reason.

Bove goes back to one of the invoice emails Cohen sent to Weisselberg. It says "pursuant to the retainer agreement"; retainer agreements can be verbal, correct? Yes.

He now wants to zero in on the payment transition from the trust to the personal account. McConney confirms that part of the issue here was that this was all new to the accounting department—trying to figure out how to pay Trump's personal expenses while he was in D.C.

Back to the 1099 forms now—one from the trust, one from Trump's personal account. Bove clarifies with McConney that there's no place on this form to break out legal services, as opposed to expenses incurred while carrying out those services, when reporting to the IRS. This is actually nonsense. One typically does not report reimbursements on a 1099, which is a non-employee income statement. But McConney plays along.

Bove goes quickly back to the OGE conflicts form signature page, which was signed by the OGE officer, as well as Trump. Doesn’t that mean that the officer concluded that the filer (which is to say Trump) was in compliance with the ethics regulations, at least based on what was on the information available to the officer? McConney assents. But this too is a weak argument. After all, the point of falsifying business records is to obscure financial misconduct, so as to enable one to file false OGE reports and have them be consistent with the business’s internal accounting documents.

It’s 12:51 p.m., and Bove is done.

"Just a few questions," Colangelo says for redirect. Do expense reimbursements usually get reported to the IRS? Colangelo asks, calling Bove out on his mischaracterization of what one should expect from a 1099. No.

Were you privy to any conversations between Trump and Weisselberg about these payments? No.

What about between Trump and Cohen? Also No.

Did you have any conversations with the three of them—that is, Trump, Weisselberg, and Cohen—about the payments? No

Were there matters Weisselberg kept you in the dark about? Yes.

Was this all happening above your head? Yes.

You were told to do something and you did it? Yes.

No further questions from Colangelo.

Bove steps back up with a single remaining question.

Bove: All of these payments to Cohen were disclosed to the IRS, right?

McConney: Yes.

The witness steps down, and Justice Merchan takes a lunch recess.

* * *

At 2:14 p.m., slightly ahead of schedule, Justice Merchan is back on the bench. And Blanche is raising several objections about whom he believes the next witness to be; he says the defense learned about this only 30 minutes ago.

The defense means to raise the same objections to the next witness and several exhibits that would come with her—to wit, that Cohen's invoices are not themselves business records, Blanche says, but inadmissible hearsay. In this case, some of the exhibits in question—the invoices—are believed to be stamped by the witness, the defense contends, and are still inadmissible hearsay. The prosecution, in turn, argues that the invoices serve as clear records that the Trump Organization received and reviewed them, and then took action by making general ledger entries and cutting the checks, which is part of the crime. Blanche clarifies that he doesn’t dispute the way Assistant District Attorney Christopher Conroy just explained how the Trump Organization pays its bills. “They certainly need an invoice to pay and won’t pay without an invoice,” he says. But “the invoice itself that causes them to pay is being offered for the truth of the matter asserted,” Blanche continues, “meaning the statements by Mr. Cohen in this case are being offered as a business record exception to the hearsay rule. That’s our objection.”

This witness turns out to be Deborah Tarasoff. The prosecution has not yet called her to the stand—we're still debating the admissibility of People’s Exhibit 42, I believe, which are apparently a series of canceled checks.

Justice Merchan says she is certainly capable of testifying that the information on these checks is standard business practice—and he rules that the checks can come in as business records or even as "real evidence."

Justice Merchan agrees with Conroy that she's going to say things like, yes, this was the check I generated, I received it back from the bank, demonstrated that it was cashed. Same check number, same payee, same amount.

Blanche says the defense objects that while it may be a business record of a bank, it is not a business record of the Trump Organization.

OK, noted, overruled, rules Justice Merchan.

At 2:24 p.m., we're bringing the jury back in to hear from Tarasoff.

* * *

Tarasoff is another long-time Trump Organization employee. She was identified as the group’s “Accounts Payable Supervisor” in the statement of facts that accompanied the indictment.

She allegedly prepared the checks used to reimburse Cohen and falsely recorded them as “legal expenses” in Trump Organization business records.

She's an older woman with white hair and glasses, wearing a blue-and-white checked shirt. She has worked for the Trump Organization for 24 years, she says.

And who owns the Trump Organization? "Correct me if I am wrong, Mr. Trump," Tarasoff says.

She's here with her attorneys, who are paid by the Trump Organization. She is here under subpoena.

Tarasoff gives us a bit of her biography: educational history, her family, and her past work experience from before she became the accounts payable supervisor for the Trump Organization.

She says the Trump Organization is made up of “a bunch” of entities. Over a hundred? I think close to it, yes.

Conroy, who is handling the direct examination for the prosecution, asks whether Tarasoff knows Rebecca Manochio? Yes, she was an administrative assistant; she is now in accounts receivable.

Alan Garten? Yes. He’s a lawyer.

How about Michael Cohen? Yes, he was a lawyer who worked there as well. He sat in two different locations on the 26th floor of Trump Tower.

Conroy asks whether she knew Jeffrey McConney, the previous witness. Yes, she says.

What does she do in accounts payable? She gets approved bills, enters them into the system, and cuts the checks. Easy as that.

How about Allen Weisselberg? He was the CFO, she says. She worked about as closely with him as she did with McConney, a little less maybe.

Weisselberg "had his hands in everything," says Tarasoff, neutrally.

Who was Rhona Graff? She was Trump's assistant.

Did Tarasoff see Trump around the office during 2015 to early 2017? Yes, she did.

Did Tarasoff have much authority to make decisions in accounts payable? Not really.

Did she just follow directions? Yes.

Whom did she report to? Basically Jeff McConney.

How many entities did she handle accounts payable for? Between 50 and 60, she says, maybe more.

Here’s accounting 101, according to Tarasoff: "Accounts receivable, ya get the money in. Accounts payable, ya give it out."

Who could approve invoices? Weisselberg, McConney, "obviously Mr. Trump," anyone in the legal department.

Did the dollar amount impact who could approve a given invoice? Yes, under a certain amount Weisselberg could approve an invoice, but over a certain amount, it had to be approved by Trump himself, Don Jr., or Eric.

So far, Tarasoff is just corroborating McConney's testimony.

Before 2015, that threshold dollar amount was $2,500; after that, it was $10,000. The general ledger had codes associated with each entity. Like McConney, Tarasoff testifies that Trump's personal account was DJT.

Once Tarasoff would cut a check from the DJT account in the period 2016-17, what would happen?

Before Trump was president, she'd cut the check with the invoice for it, and she'd bring the package to Graff for Trump to sign the check. She'd get it back signed, invoice and check still stapled together.

Were you responsible for reimbursing expenses to vendors? Yes.

Did you require proof of expense? Yes, a receipt.

How much would the Trump Organization usually reimburse for an expense? The amount of the expense.

We're now moving from who could approve invoices to who could sign checks.

Who could sign checks for Trump's personal account? Only Mr. Trump, regardless of amount, Tarasoff says.

Did an approved invoice mean that a check had to be signed? Tarasoff says the person signing the check could decide not to sign.

Did Trump have to sign a check just because Weisselberg had approved an invoice? No, if he didn't want to sign it, he didn't sign it. It happened: Trump would write VOID on a check and send it back.

How did she know Trump wrote it? It was signed in black sharpie—that's what Trump uses.

Tarasoff says she handled accounts payable for Trump's personal account and the trust account.

Once Trump became president, did he still sign all the checks for the personal account? Yes, says Tarasoff.

Tarasoff fidgets a bit with her hands, but otherwise she's pretty unflappable. She answers yes or no when she's confident in the answer, and "I don't recall" when she's not that confident. She’s pretty credible.

Conroy is zeroing in now on payments made to Cohen during this period, and Tarasoff continues to corroborate McConney's testimony as to how they were handled.

Conroy hands up a thumb drive, and Tarasoff affirms that she reviewed the documents contained therein. Conroy enters exhibits into evidence from this thumb drive, and Blanche objects to a slew of them, per our conversation after lunch but before the jury came back. Justice Merchan lets them in.

The Trump presidency created problems for the accounts payable department. The reason was not the travel ban or the Russia investigation—it was that Trump had to sign all checks from his personal account, Tarasoff says, but he wasn't in New York anymore to do so.

How did this work? Rebecca Manochio would FedEx them to the White House for him to sign. In D.C., Tarasoff isn't sure what happened to them or how they were handled. She would just get the checks back, signed by "Mr. Trump."

Once she got them back, she says she'd pull the signed check and backup material apart, mail out the check, and file the supporting documentation into the records of the Trump Organization.

Conroy now pulls up People Exhibit 37A, which is an email from McConney to Tarasoff dated February 15, 2017. The email’s subject is, "FW: $$".

A couple of pages down, Conroy points out the invoice, which Tarasoff confirms.

Conroy now pulls up People's Exhibit 1: it's the same email chain as 37, but there's a stamp.

"That's my stamp," Tarasoff says.

The stamp reads: “ACCOUNTS PAYABLE, entity DJTREV [the code for the trust], and 51505 [code for legal fees]".

The vendor/payee is Michael Cohen, and the invoice amount is $35,000. The ledger distribution reads "LEGAL EXPENSE".

We see a few screenshots of the computerized ledger interface for the Trump Organization. It does look quite antiquated, the kind of design you'd see in the late 1990s or early 2000s in the Windows operating systems.

Conroy displays People's Exhibit 4. It's a copy of a check—two identical stubs; the check is for $70,000, and there are two line items, one for Jan 2017, one for Feb 2017, each for $35,000. This is one of the 11 checks from the indictment, and the reason there are 11, not 12.

Being over $10,000, the $70,000 check cut from the trust account needed two signatures. This one had Eric Trump’s and Weisselberg’s. The word “VOID” is also visible three times, but that only shows up when you photocopy it, Tarasoff says. The check was not actually void.

Now we see People's Exhibit 37B, and Conroy pulls out the top email. All of a sudden, we're another long lather, rinse, repeat cycle, going through all 11 checks.

At 3:32 p.m., Justice Merchan mercifully calls for a brief recess.

Reporters in the overflow room are speculating who the next witness will be tomorrow: Some think it'll be Rebecca Manochio.

At 3:44 p.m., we hear the judge call for the witness to return. We move quickly through the exhibits now, as Tarasoff confirms her accounts payable stamp on invoices, vouchers, checks, and the like, all of which we've already seen.

At 3:56 p.m., there are no further questions from Conroy.

Blanche steps up for his cross-examination, and begins by asking Tarasoff questions about Trump's family—Don Jr., Eric, and Ivanka—and whether she worked with them during her time at the Trump Organization. Yes, yes, and yes, she says.

As Blanche continues his cross, Trump has turned his body to face his lawyer, one arm leaned over the back of the chair.

Blanche asks about how Tarasoff would take a check to Trump and sometimes get it back unsigned. Tarasoff says that she didn't interact with Trump himself all that much, more so McConney and Weisselberg.

No, she didn't have the authority to just cut a check on her own, though, she says, she never got permission from Trump himself. There were intermediaries. She wasn’t that high up.

It was a quick cross. Tarasoff’s is a scalp Trump’s defense team doesn’t want.

At 4:02 p.m., there are no further questions, and Tarasoff steps down.

"Jurors, we're going to stop a little early today," Justice Merchan says. He dismisses them.

Steinglass stands and requests to recall summary witness Georgia Longstreet-Joseph to admit additional tweets and truths from Trump, as well as a summary witness to go through texts from People 171-A, certain items of which were redacted. He also wants to address the defense’s arguments regarding the exhibits.

It's just not true, Steinglass says, that defense counsel has not been given a heads up as to what the exhibits are. The prosecution designated all its exhibits by March 15, then a few additional ones by March 25.

Steinglass says he has been notifying defense counsel the day before who the next day's witnesses are going to be. We've made this clear because the defendant has been violating the gag order, he says. The defense has the witness list, has had it for months. "I don't like the impression that we're somehow sandbagging the defense," says Steinglass.

Steinglass also says that shortly after they excused Longstreet, they put on the record at a bench conference that they intended to recall her to go through exhibits, including a tweet that will come up for a later witness.

"I'm looking at the Jan 29, 2024, witness list, and Ms. Longstreet is not on it," Blanche replies, saying he's happy to be told he’s wrong.

Part of the cross-examination was the important point that however many thousands of social media posts Longstreet was tasked with reviewing, there are only seven to nine that she was asked to identify and admit into evidence, says Blanche. Blanche admits that Justice Merchan can allow her to be recalled.

What's the prejudice, to you? asks Justice Merchan. "I'm not really following. If [Longstreet] takes the stand [again] and testifies to additional tweets and truths, what's the prejudice?" Merchan clarifies that we're talking about three additional social media posts.

I'm not sure why that matters, Your Honor, Blanche says, shrugging.

Merchan is unmoved. Steinglass had intended to call Longstreet back today, but it looks like we won't get to her until Thursday or Friday now.

Steinglass will notify defense of the name of a new witness the prosecution plans to call tomorrow as soon as we're off the record.

Generally speaking, how are we doing on scheduling? asks Justice Merchan.

Well, says Steinglass.

The judge responds: Can I get a bit more than that?

This week plus next week, and possibly into the week after. Very, very rough estimate is that we will be done two weeks from tomorrow.

A reminder that court is not meeting on May 17, 24, and 27.

With that, Merchan thanks everyone, and bids us farewell until tomorrow.

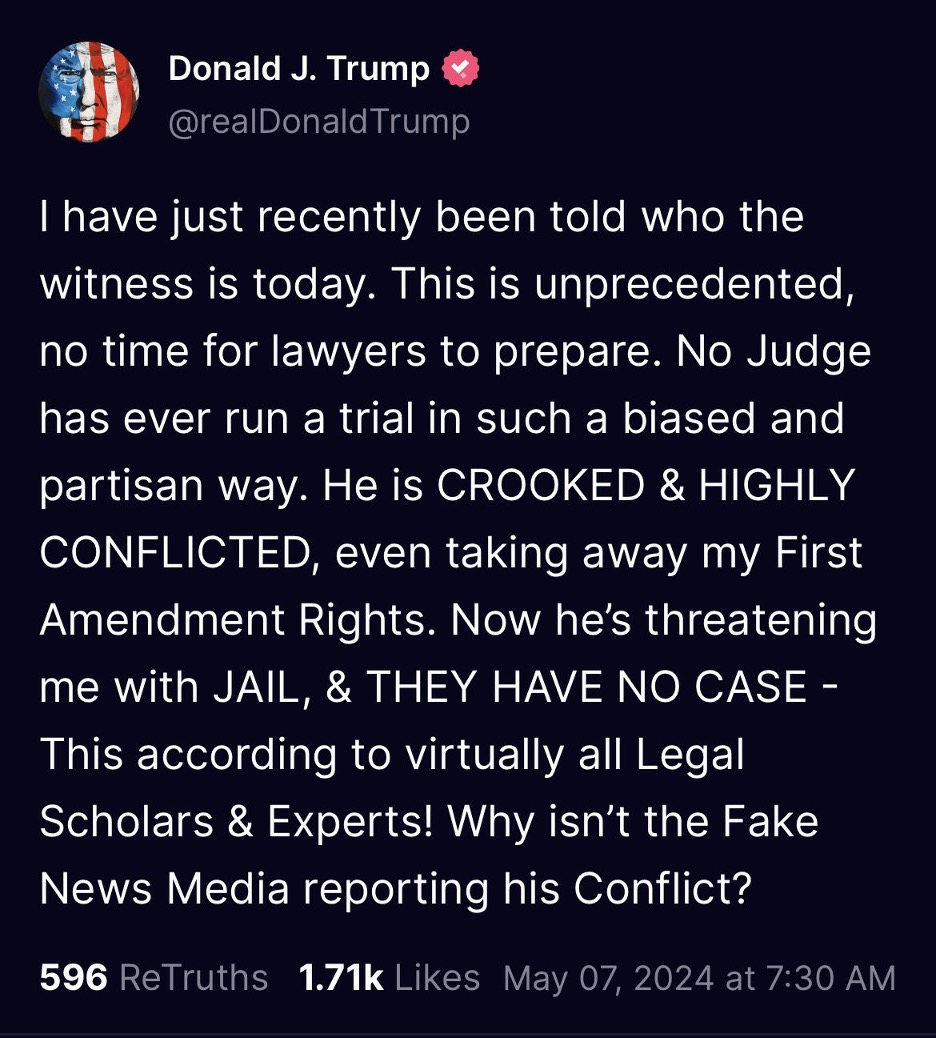

May 7, 2024

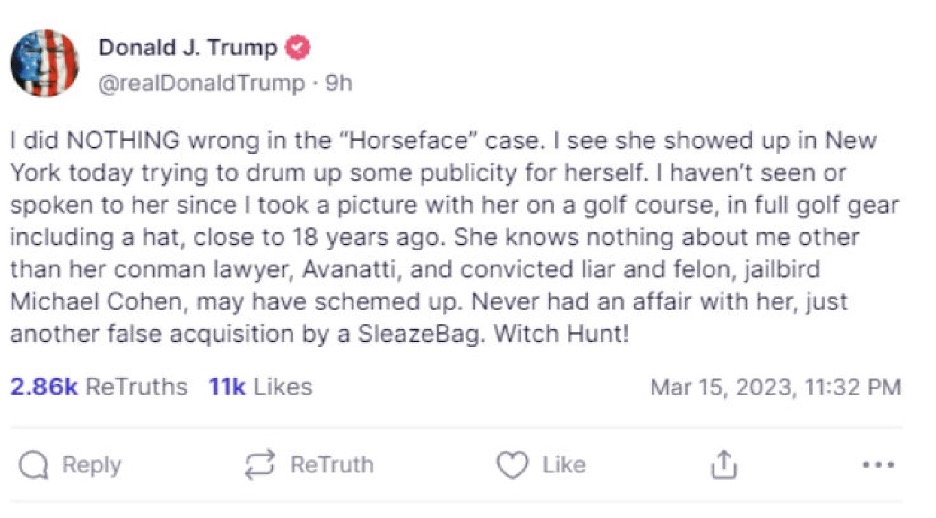

The press and the public don’t know yet for sure who today’s witness is, but the defendant, who found out yesterday, doesn’t seem too happy about it.

Trump appears to have deleted that post from his Truth Social account, probably wise considering Justice Merchan’s jail threats yesterday.

But, now, as we sit in the courtroom and overflow room, the Associated Press is reporting that today's witness will be none other than Stormy Daniels—one of the women who started it all.

At 9:12 a.m., the prosecution enters.

Assistant District Attorney Joshua Steinglass walks in first, followed by co-counsel, Matthew Colangelo, Susan Hoffinger, and Christopher Conroy.

At 9:24 a.m., Trump, donning a gold tie and blue suit, walks in with an entourage including Eric Trump and his lead defense lawyers—Todd Blanche, Emil Bove, and Susan Necheles. Alina Habba and Boris Epshteyn are also in tow, though they are not part of the legal team for this case.

The photographers shuffle in and do their thing. The sketch artists are already sketching.

Blanche walks across to the prosecution's table to whisper something to Steinglass.

At 9:28 a.m., it’s all-rise time, and Justice Merchan sweeps in, resplendent in his robes, judicial authority radiating from his presence.

Necheles rises to renew Trump's objection to Daniels testifying, particularly about any "sexual details," which she says have no relevance and are highly prejudicial in a case that—she notes with some justice—is supposed to be about falsified business records.

By details, Justice Merchan asks, you mean any more than just "we had sex"? Yes, Necheles says.

For the prosecution, Susan Hoffinger argues that the details of the encounter are important; it's important for the prosecution to establish Daniels’s credibility and the reasons why she did what she did. The prosecution has worked hard to omit details that are too salacious, but general details of what occurred are significant.

Can you give me a sense? Justice Merchan asks.

Hoffinger says that the key is how Daniels ended up having a sexual encounter with Trump, the full conversation that occurred in the hotel room. But the sexual act itself will be very basic. There will be no descriptions of genitalia or anything of that nature, Hoffinger says.

"It isn't needed in this case," says Necheles of the whole line of evidence. "This is a case about books and records."

But Justice Merchan is satisfied with what Hoffinger says the prosecution plans to elicit; he agrees that Daniels has credibility issues, and that the People thus get to establish certain background information to establish her credibility.

The jury enters the courtroom.

After the jurors are seated, the prosecution calls its next witness, who turns out to be—drumroll, please—a woman named Sally Franklin, a senior vice president and executive managing editor at Penguin Random House.

Why Franklin is here becomes immediately clear.

Are you familiar with a book called “Trump: How to Get Rich?” Yes. It was published by one of her imprints, Ballantine Books. Franklin is here as a summary witness because the prosecution needs to get certain passages from the book into evidence. She is here under subpoena. Penguin Random House has no dog in this fight.

The prosecution moves to introduce People’s Exhibit 413—the cover of “Trump: How to Get Rich: Big deals from the star of The Apprentice”—written by Trump “with Meredith McIver.” Franklin describes the cover, which is dominated by the word “TRUMP.” The book was first published in 2004.

We turn to page three from the book, only two sentences of which are unredacted: "I am the chairman and president of the Trump organization. I like saying that because it means a great deal to me."

Another excerpt: Pay Attention to the Details. “If you don’t know every aspect of what you’re doing, down to the paper clips, you’re setting yourself up for some unwelcome surprises.”

Another: Sometimes You Still Have to Screw Them. "For many years, I've said that if someone screws you, screw them back…. When somebody hurts you, just go after them as viciously and violently as you can. Like it says in the Bible, an eye for an eye."

And one more: “3:00 p.m. Allen Weisselberg, my CFO, comes in for a meeting. He's been with me for thirty years and keeps a handle on everything, which is not an easy job. He runs things beautifully. His team is tight and fast, and so are our meetings.”

We move on to another entry in Trump's oeuvre: “TRUMP: Think Like a Billionaire, Everything You Need to Know About Success, Real Estate, and Life,” by Trump—again with McIver. Trump again is alone on the cover.

The book was published by Ballantine, first in hardcover in 2004.

Recall that almost none of the jurors have read any of these books in full. One potential juror had read “The Art of the Deal” but was unsure if he read “How to Get Rich.” Another potential juror had made a point to speak directly to Trump when he said, “I never read any of your books.”

A choice excerpt from “Think Like a Billionaire”: "When you are working with a decorator, make sure you ask to see all of the invoices. Decorators are by nature honest people, but you should be double-checking regardless.”

Reading book excerpts to a jury by a high-profile author as a records custodian witness is probably not the reason Franklin went into publishing, yet she’s a gamer about it. She continues to read excerpts from the books, speaking to Trump's attention to financial details, penny pinching, belief in inevitable sexual relations between him and other women, and other themes, ostensibly in Trump's own words but actually in the words of the elusive Meredith McIver.

At 9:58 a.m., there are no further questions from the prosecution.

Blanche steps up, and asks Franklin if she's paying for her own lawyers. She is not. Her employer is covering her legal fees.

Blanche asks about McIver's role. In these books. Is she a ghostwriter? Franklin is not sure the exact details of her contribution.

That’s because the role a “with” author plays varies, Blanche suggests, depending on the book, right? Yes, she says.

It seems pretty clear what Blanche is doing right now: He's calling into question whether we can take the words in the pages of Trump's book as Trump's words and Trump's beliefs.

At 10:03 a.m., there are no further questions from Blanche, and the prosecution begins redirect.

In your experience, did ghostwriters ever write entire books or create content without the author's knowledge? No, Franklin says. The ghostwriter works for the author. Rebecca Mangold, for the prosecution, offers three more exhibits into evidence and Blanche asks to approach the bench. In the sidebar, Blanche challenges these exhibits, arguing that the prosecution had failed to produce them to the defense. In response, Mangold explains that the exhibits are intended to establish that Trump was aware of the statements made in the books, since Blanche just spent most of the cross-examination establishing Trump’s use of a ghostwriter and thus challenging the attribution—to which Blanche pushes back. Merchan notes the objection and overrules it.

With that, the prosecution resumes the redirect examination, and exhibits 413F, 413G, and 413H are offered into evidence.

They turn out to be more excerpts from “Trump: How to Get Rich”—to wit, the epigraph page with a purported quotation from Trump’s mother: "Trust in God and be true to yourself."

The acknowledgments page includes a thanks to McIver, a "woman of many talents," who was also an executive assistant at the Trump office, has "heard everything," and has "taken good notes."

"It's important to have an editor who asks the tough questions," reads another line of the acknowledgments page, getting a very subdued chuckle from the press in the courtroom.

Still another excerpt seems pretty on-point in light of McConney’s and Tarasoff’s testimony yesterday: "For me there's nothing worse than a computer signing checks .... When you sign a check yourself, you're seeing what's really going on inside your business."

No further questions from the prosecution, but Blanche wants another bite at the apple.

He puts up Exhibit 414G, an excerpt from the acknowledgments page, and asks whether it’s just the ghostwriter “listing folks that she wants to thank for her help.”

Hearing a yes, Blanche says he has no further questions. Neither does the prosecution, so the witness steps down.

Attorneys from both sides huddle around Justice Merchan for a sidebar, as Emil Bove stays seated at the defense table, in conversation with Trump.

"People, your next witness, please," says the judge.

“The People call Stormy Daniels."

* * *

It is a moment. Trials have long periods of boredom punctuated by moments of heightened experience and extreme drama. This is one of those of moments.

Stormy Daniels enters, dressed in black, her hair tied up behind her, glasses pushed up on her head.

Her voice starts out a bit shaky as she spells her name. She takes her glasses off her head and puts them on as Susan Hoffinger begins her direct examination.

She prefers to use the name Stormy Daniels, not Stephanie Clifford.

She was born and raised in Louisiana to a "very low income family" with a single working mom. She started in the magnet high school program and wanted to be a veterinarian, and she graduated high school in the top 10 percent of the country. Despite getting a full-ride scholarship to Texas A&M, the related costs were still too high, so she was not able to go.

Her extracurricular activities in high school? Ballet, equestrian club, she was the editor of her high school newspaper. She loved horses and worked at a stable, where she taught handicap riding lessons and shoveled manure.

Daniels talks quickly, and Hoffinger asks her to slow down a bit. She's telling us now how she got into dancing, which was more lucrative and less time consuming than shoveling manure.

At Christmas time her senior year of high school, she says, she left home because her mother would just vanish for days at a time. She had just turned 17. She says she doesn’t know her mother to have been addict, which would have at least been an excuse.

She continues to recount her career path and the thinking behind her decisions, from dancing to nude modeling to her work in adult films—which she wrote, directed, and performed in.

Each one "tops out on a pay grade," she says. As she tells it, each job led to a logical next step, much like any career would. Why would anyone seek a next job? More money, better opportunities.

Daniels acted in a few mainstream Hollywood films—"The 40-Year-Old Virgin," "Knocked Up," "Superbad"—and a few TV shows, such as "Dirt" with Courtney Cox. She has been in music videos too: Maroon 5, Rob Zombie, and others.

In your podcast, "Beyond the Norm," asks Hoffinger, did she discuss Trump and her experiences with him? Yes, of course.

Why did she stop the podcast? Because she got fired, Daniels answers frankly, and that was because she didn't want to keep talking about the single subject of Trump and her encounter with him.

In 2009, did you consider running for Louisiana Senate as a Republican? Daniels laughs, and explains to the jury that there was a "Draft Stormy" campaign to go against an opponent who opposed reproductive rights and was anti-sex education, she says. It was really a joke. She never wanted to be a senator.

Hoffinger comes now to the time of her encounter with Trump in July 2006. It was at a celebrity golf tournament, when she was 27 and while she was employed by Wicked Entertainment, which is an adult entertainment company that was sponsoring a hole at the tournament.

"It was funny, one of the adult film companies sponsoring one of the holes," Daniels jokes.

Get it?

Daniels says she says she met Trump on the golf course at this tournament in Lake Tahoe. The meeting was brief; she said hello and posed for pictures with him, as she did with every other celebrity player in the tournament.

What did you know about Trump at the time? Well, that he was obviously a golfer, and that he had a television show that I had never seen, called "Celebrity Apprentice," plus reality TV things.

She continues to talk fast, and the court reporter asks her to repeat things often.

At the time, she says, she didn't know his age, but "I knew that he was old, probably older than my father," recounting another interaction at the gift room of the 2006 Lake Tahoe celebrity golf tournament. This interaction wasn’t much different than others she had that day with other celebrity golf tournament contestants. They would “come through, get a gift bag, check out the products, [and] pose for photos.”

Do you see Mr. Trump in the courtroom today? Yes. Can you point him out and indicate an article of clothing that he is wearing? She leans over, extends a hand, and points in Trump's direction. She says, "Navy blue jacket, second at the table."

Hoffinger now hands up a thumb drive of evidence. We see People's Exhibit 226, a photo of Daniels and Trump in the gift room of the golf tournament, and People's Exhibit 227, a photo of Trump on the golf course, displayed on screens throughout the courtroom.

Daniels says that she spoke briefly with Trump in the gift room, after which Trump’s bodyguard, Keith Schiller, approached her and told her that Trump would like to ask her to dinner. She initially rebuffed the invitation with a “F’ no”—meaning fuck no. Schiller then took Daniels’s number and messaged her until she saved it in her phone.

Daniels had a work dinner she didn't want to go to, so her publicist convinced her to ditch it and have dinner with Trump instead. "What could possibly go wrong?" Daniels's publicist asked her. She knows this story is funny—even now.

She told a friend, she says, about what was going on and then headed to the Harris Hotel, where Trump was staying, to have dinner with him on the penthouse level in his suite.

Hoffinger asks her again to slow down for the court reporter. Her hurried speech doesn't seem as though it's from nerves; it’s just kind of how she talks.

The first sign that something was very wrong was when Schiller dropped her off at Trump’s hotel room, and he was wearing silk or satin pajamas when he greeted Daniels.

"Like two-piece pajamas, that I immediately made fun of him for, and said does Mr. [Hugh] Hefner know you stole his pajamas?” said Daniels. She asked him to change clothes, which Trump did quickly.

They traded pleasantries at the dining room table of the suite.

Hoffinger asks if they discussed her "difficult childhood," but the defense objects, and Merchan sustains the objection.

Daniels says they discussed the adult film industry, and Trump had a lot of questions about the business side of it, which she thought was "cool." Whereas most people asked about what her favorite sex position was, he had "very well thought out business questions" about unions, residuals, health insurance, STD/STI testing, and whether the production companies had doctors on staff.

Did Trump ever ask you if you had been tested? Yes, he asked if I ever had a "bad test," and I told him I was tested regularly and never tested positive for anything.

Daniels says she explained that adult film performers are “like WWE, like wrestling.” To which Trump responded that he was friends with WWE’s owner, Vince McMahon.

They then spoke about how Trump sometimes made appearances on WWE, and how, at the time, Trump was part of a “scenario” or “set-up” where if he “lost” a bet on a fight, McMahon would shave Trump’s head. "Donald Trump has always been very famous for his do," she says. She asked what he was going to do if he loses, because "You do not have the head design to be without hair." Trump told her that he wasn’t worried, since the “bet” was predetermined.

During this time they also spoke about Melania Trump. "She is very beautiful. What about your wife?" she asked. Daniels recalls him saying that they don't sleep in the same room, however.

Hoffinger asks if they discussed Trump’s presence on some magazine covers, and Daniels says that they did. "He would ask me questions and then not let me finish with the answer. He kept cutting me off, and it was almost like he wanted to one-up me, which was just really hilarious when you think about it."

Daniels says she quickly tired of his arrogance and wanted to head home. But she didn’t. Instead, she “snapped” and asked if Trump was “always this rude, arrogant and pompous.”

This leads her to the now-familiar story about her spanking Trump with a rolled-up magazine. During their conversation about magazine covers, Trump had pulled out a new edition of a financial magazine, with Trump on the cover. After confronting Trump, Daniels says, she told him that someone should spank him with the magazine that laid on the table before them. “That’s the only interest I have in that magazine. Otherwise, I am leaving,” she told Trump. Trump then rolled up the magazine and, according to Daniels, gave her a look insinuating that he dared her to do it.

Daniels took the magazine from Trump, told him to turn around, and swatted him with it "right on the butt." After which he was "much more polite."

During this conversation, Daniels says that Trump told her that she should go on "The Apprentice." "You remind me of my daughter because she is smart and blonde and beautiful and people underestimate her as well," she reports him saying.

Trump tells Daniels that she should go on the show and prove that she is “not just a dumb bimbo” and that she is more than people think, and in return he would get attention for having this “crazy idea.” Daniels says she was skeptical, telling Trump that she wasn’t a “business” person and that there was no possibility that she would win—to which Trump replied that she doesn’t have to win. She then expressed concerns about losing on the first episode, which she says would make her look bad and like the “idiot” people thought she was. Trump reminded her that—like the WWE wrestling “set-up” he participated in—he can have the outcome of "The Apprentice" be predetermined, and give her some advantage—like informing her of challenges in advance—to ensure that she at least has a good showing.

After some discussion of Daniels’s career aspirations, her relationship with her adult-film colleagues, and a phone call to a friend she made from the hotel room, Hoffinger asks if Daniels at any point needed to use the restroom during her time with Trump.

But just as Daniels begins to answer, Justice Merchan calls for a brief recess.

After Daniels and the jurors are excused, Merchan asks the prosecution and the defense to approach the bench. He wants to address an issue with Trump himself, who apparently has been muttering expletives from the defense’s table throughout Daniels’s testimony. Merchan says to Blanche, “I understand that your client is upset at this point, but he is cursing audibly, and he is shaking his head visually and that’s contemptuous. It has the potential to intimidate the witness and the jury can see that.”

Blanche agrees to talk to Trump about it during the break.

* * *

After the recess, with both the witness and the jury out of the room, the judge addresses Hoffinger: “The degree of detail that we're going into here is just unnecessary." We don't need the details of conversations, he says. We don’t need details on what the hotel suite and foyer look like, matters about which Daniels had gone on at some length. Justice Merchan wants to keep the conversation focused. He wants to keep things narrow. He wants to keep them not salacious.

The jurors are seated and Daniels resumes: She had been at the dinner in Trump’s room for a while, though there had been no actual dinner. She had, however, drunk a couple bottles of water, and she needed to use the bathroom. So Trump directed her to the facilities, which were through a bedroom in the suite, to a "very large beautiful bathroom."

Daniels said she noticed an unmade bed on her way in, and a leather-looking toiletry bag on the counter. She looked inside, she admits, saying she wasn’t proud of having done so. She saw Old Spice and Pert Plus, and thought that was "amusing and odd." She also saw gold tweezers and other gilded things. "I wish I had a cellphone camera. If I did, I definitely would have taken a picture of that,” Daniels says.

She washed up and exited.

Daniels expected to go back to the table and say it was time to leave, but when she opened the door, Trump had come into the bedroom and was on the bed, wearing boxer shorts.

"At first, I was just startled, like a jump scare. I wasn't expecting someone to be there, especially minus a lot of clothing," she says. She felt the blood leave her hands and her feet, like when you stand up too fast and everything started spinning.

Then she started asking herself what she had done wrong. "Oh my god, what did I misread to get here?" she remembers thinking.

She says she laughed nervously, went to step around him on the bed and leave, and it all felt like slow motion. He stood up between her and the door but "not in a threatening manner," she clarifies.

"I thought this is what you wanted, if you ever wanted to get out of that trailer park—" Daniels starts to say that's what Trump told her to get her to stay, but there’s an objection, and it is sustained.

And then, she says, she blacked out, though she clarifies that she was not drugged and did not have any alcohol. Another objection, which is overruled.

Justice Merchan cuts it off right there, and asks counsel to approach.

In the sidebar, Necheles explains that Daniels’s testimony is “making it sound like she was drugged” by explaining that she was dizzy and that she blacked out. Hoffinger offers a clarification that Daniels was, in fact, not drugged.

The objection is sustained.

Hoffinger resumes and asks Daniels to slow down again. She clarifies that Daniels was not drugged in any way, nor had she had any alcohol in any way. Daniels confirms both.

Did you feel threatened by him? No, not physically, but there was an imbalance of power, for sure. He was bigger and blocking the way, but I was not threatened, verbally or physically.

Hoffinger asks her to describe the sexual encounter "very briefly," Daniels starts to describe the fact that she had her clothes and shoes off and started in "missionary position"—objection, sustained.

Did you end up having sex with him on the bed? Yes.

Do you have a recollection of feeling something unusual? An objection is once again sustained.

What do you remember? That I was staring at the ceiling, that I didn't know how I got there.

Did you touch his skin? Yes. An objection is yet again sustained.

Was he wearing a condom? No.

Was that concerning to you? Yes.

Did you say anything about it? No, I didn't say anything at all.

Daniels remembers the entire sexual encounter to be brief.

"Let's get together again, honey bunch," she says Trump told her, and she just wanted to leave, she says

Did you say no at any point? No.

Daniels describes difficulty getting dressed after having sex with Trump: “It was really hard to get my shoes on, my hands were shaking so hard.”

Hoffinger asks if Trump said or did anything when Daniels went to leave. She explains that he told her they had to get together again, that they were “fantastic” together, and that he wanted to get her on "The Apprentice."

"And that was it. He didn't give me anything. He didn’t offer to pay me or anything or a cell phone number or anything like that," she says.

Did he ask you to keep this confidential? No.

Did he express any concern about his wife? No.

Did you end up having dinner with him that night? No.

Did you tell people about what happened? "I told very few people that we actually had sex because I felt ashamed that I didn't stop it, that I didn’t say no," Daniels says.

Daniels says she didn’t remember all of the details of the event initially, but some of them came back to her over the years. Hoffinger asks about those. An objection is overruled. Hoffinger tries to clarify there were certain things Daniels always remembered, like the fact that they had sex, but when she continues, there’s another objection from Necheles, and a sidebar results.

The testimony has been stop-and-go so far, with frequent objections and sidebars.

Daniels says she saw Trump again in Tahoe the next day at her hotel, at a nightclub restaurant downstairs.

The jurors are now fully rapt with attention once again, and their heads ping pong back and forth between Hoffinger and Daniels, much like spectators at a tennis match.

Daniels says Trump was in the club with his friend, Ben Roethlisberger, and Trump introduced her as "his little friend Stormy" to "Big Ben," the football player, who let her try on his Super Bowl ring. Trump continued to talk about getting Daniels on "The Apprentice."

Daniels says she told her friend and photographer Keith—who is not to be confused with Keith Schiller, Trump's bodyguard—her makeup artist and confidante, and her personal assistant, but not many others, about the sexual encounter.

In the wake of the encounter, she says, Trump would call her often. "I would always put him on speaker phone. I thought it was funny," she says. As a result, she claims, dozens of people would hear these conversations: "it was not a secret."

During these calls, Trump would give her updates (or offer "non-updates") about her appearance on "The Apprentice." He would ask Daniels if she missed him, and he always called her “honey bunch.”

She starts to digress at the next question, and Justice Merchan asks her to "please just answer the question."

Daniels says Trump gave her his personal assistant Rona's phone number in late summer 2006.

She is answering more briefly and succinctly now, apparently taking Justice Merchan's instructions to heart.

There are exhibits now too. The contact page in Daniels's iPhone for Rona Graff, Trump’s assistant, which she saved as "DTrump Rona," and another contact page (not from an iPhone) for "Stormy" with Daniels's phone number (with only the last four digits unredacted).

Daniels says Trump reached out and asked her to attend a party for his vodka brand, which she accepted. She did this to maintain the relationship because the "chance to be on 'The Apprentice'" was still up in the air. She was especially keen to keep "The Apprentice" job alive, because Trump had begun to pitch it as an opportunity for writing and directing.

At the vodka event, Trump greeted her, unconcerned by the optics of her being an adult entertainment actor, Daniels says, and he introduced her to his friend "Karen"—which is to say Karen McDougal.

She says he asked her to go back with him that night, but she lied to him that her and a friend were flying out on a girls' trip.

Hoffinger fast forwards now to 2007, when she says Trump told her to contact him if she was ever in New York. She "hit him up," she says, to get him to come to the club where she was performing, but he "invited me to his office tower" instead.

Why did she go? "It was a public place, lots of witnesses"; an objection is sustained. This testimony is potentially significant because it corroborates the earlier testimony by Graff that she may have seen Stormy Daniels in the building at this time. Daniels says she had a "very brief" discussion with Trump in his office in Trump Tower. She says he was very busy.

There was no movement on getting her on "The Apprentice."

"It was always, 'I'm still working on "The Apprentice" thing,'" Daniels says.

Now to the 2007 Miss USA Pageant, tickets to which Trump had left under Daniels's name at will call, she says. Then, in the summer of 2007, she met with Trump in Los Angeles for dinner at his bungalow in the Beverly Hills Hotel. These interactions did not seem nearly as significant as the sexual encounter in the hotel suite, but, for each one, Hoffinger made it a point to ask Daniels three questions: Did Trump ask her to keep their sexual encounter confidential moving forward? Did he seem worried about its disclosure? Did he seem concerned about his wife finding out? And for each interaction, Daniels’s answers were the same: no, no, and no.

Did you tell your boyfriend what happened in the hotel with Trump? Not the sexual part. Because I was ashamed, she says.

Daniels's boyfriend waited outside while she went into the bungalow, she says. Trump was busy, watching TV—a documentary about some sailors who got killed by a shark when the submarine sank—and kept trying to "make sexual advances." But there was no "real update" on "The Apprentice."

Once again, Daniels testifies that Trump still did not ask her to keep the sexual encounter confidential, nor did he seem concerned about it.

Trump called her a few more times—once to tell her he couldn't get her on "The Apprentice" ("he had been overruled by someone higher up’s wife having a problem. He owed it to them to go with their opinion, I guess"), Daniels says.

Eventually, Daniels says she stopped answering his calls and moved on with her life.

Between January 2008 and May 2011, she testifies, her life was "pretty awesome." She got a raise. She directed movies. She started doing more mainstream films. She got married. And she had a daughter.

Then, May 2011, she says she agreed to be interviewed for a magazine called InTouch—a "sort of tabloid."

She learned that someone had sold a story about her to a magazine, so she freaked out. "I don't know who leaked it. I just had my daughter," she says.

Daniels says that Gina Rodriguez told her that she could either take control of it and get paid, or that someone else would make money from the story, and who knows what they'll say. She was supposed to be paid $15,000, and was doing less work at the time because she had just had her daughter.

Did you discuss with InTouch all of the details of what happened in the room? No, I tried to keep it fairly light-hearted, and quick and to the point.

InTouch didn't end up running the story, and Daniels says she didn’t know why at the time.

Hoffinger asks to approach. In a sidebar, she says that this is the point at which she would elicit testimony regarding an incident in a parking lot in 2011, which was brought out during Davidson’s cross-examination. Necheles objects but mentions that the defense will be going into the fact that Daniels owes Trump money over Daniels’s failed defamation suit against him. The parking lot incident was the basis of that litigation, so Justice Merchan allows the prosecution to proceed with that line of questioning. “I think the jury is entitled to know what led up to that, which you introduced,” he tells Necheles.

After Daniels was interviewed by InTouch, she says, she had a scary experience in June 2011 in a parking lot in Las Vegas. She says she was approached by a man who threatened her and her baby and told her "not to continue to tell my story"—the story, that is, about her encounter with Trump.

She says she didn't tell the police about the incident because she was scared. She didn’t want more of the story to get out, she says, because of her daughter, and because her daughter’s father was struggling at the time and never knew about the sexual dimensions of the encounter in the first place.

Hoffinger fast forwards again to October 2011, when Rodriguez told Daniels that a story about her had been published on a celebrity gossip site called TheDirty.com.

Daniels says she never gave the site the information behind the story, nor had she ever heard about it before. And she wanted the story taken down.

She describes freaking out about the story, crying and hyperventilating, and says that when Rodriguez asked if her lawyer—another Keith, Keith Davidson this time—should work to have the story taken down. Daniels said he should, and it was taken down a bit later.

Once Trump announced his presidential candidacy, Daniels says Rodriguez reached out to her and mentioned that she could sell the story again—making money for both her and Daniels.

Justice Merchan has been keeping Daniels’s testimony on a pretty short leash, allowing frequent objections from the defense for leading the witness, and steering her back to the specific questions at hand.

Were you aware in early October 2016 of the "Access Hollywood" tape coming out publicly? Yes, Gina told me.

Was she successful in selling your story before the "Access Hollywood" tape came out? No.

Did you continue to agree that Rodriguez could keep trying to sell the story? Yes, I told her she could keep trying. More people were calling.

But Daniels says her motivation wasn't money; it was about getting the story out. And in October 2016, she says she learned through Rodriguez that Trump and Cohen were interested in buying the rights to her story.

Daniels says she understood Trump and Cohen to be interested in paying for the story and killing it, which would be the best-case scenario for her. That way, her partner wouldn't learn about it, and the story would never get out in circumstances she couldn’t control.

She says she didn't care about the figure of $130,000—she didn't try to negotiate the money—because the money wasn't her main concern and she didn't need it. She was directing more; she moved out of expensive California; things were going well.

Daniels’s story is now linking up with the narrative and timeline established in the case so far; Daniels describes signing an NDA from Cohen, who was representing Trump. The NDA is shown as an attachment to an email with the subject line: "SD vs. RCI." The settlement sum was identified as $130,000, and wire details are included in the body of the email.

There was an urgent timing consideration, as well, because Daniels "was afraid that if it wasn't done before the nomination and things," it wouldn’t happen. Quite understandably, she didn’t trust Cohen and Trump to pay once she had stayed silent up until the election.

Daniels understood the terms of the “settlement,” she says, to be that if she was paid, that she could not tell her story, that Trump also would not tell the story, that they wouldn't contact each other's families, that they would basically pretend as though it never happened at all.

We're back to documents now. This is, after all, not an "adult film star" case, but a falsification of business records case. We see the by-now-familiar exhibits: the agreement, the sidecar agreement, the liquidated damages clause. The pseudonyms—Peggy Peterson for Daniels, David Denison for Trump. Hoffinger displays page 10 of the settlement agreement, on which Daniels says she wrote a list of eight names. These are the eight people who "knew some of the details" of the sexual encounter between her and Trump, she says.

Asked why she signed with a pseudonym, she responds that she was instructed not to use her real name.

After the ink dried on the agreement, there was a delay in payment, and Daniels was concerned about all the excuses Cohen was making for it, especially because that sum of money shouldn't matter to Trump. So, she testifies, that she assumed it was not a financial delay, but something worse.

Justice Merchan must like cliffhangers, because we stop there for a lunch recess.

Trump walks out, his entourage in tow. He doesn't look happy, but then again, he never does in this building.

* * *

After the lunch break, Justice Merchan has an announcement to make: "Just for the record, my chambers reached out to the People and to defense counsel to ask if defense counsel wanted a limiting instruction on the encounter took place in the parking lot where Ms. Daniels claimed someone threatened her," he says.

Merchan will not give such an instruction unless the defense requests it. But he makes clear that he’s open to such a request.

Blanche now stands and moves for a mistrial based on Daniels’s detailed testimony.

I'm moving for a mistrial, Blanche says, because the guardrails for this witness were thrown to the side, that all kinds of highly prejudicial material came into evidence, and that there's no way to unring the bell. It was so prejudicial to Trump and the facts given in this case, that there's no remedy the court can fashion that will undo the damage, he says.

Details about Daniels being blacked out, about Trump’s not wearing a condom, the comparative height of the two individuals, the power dynamic between them, the statement about her wanting out of the trailer park, Blanche argues, all have nothing to do with this case and are extraordinarily prejudicial.