Summary: Appointment of USCIS Director Cuccinelli Violates Federal Vacancies Reform Act, Court Rules

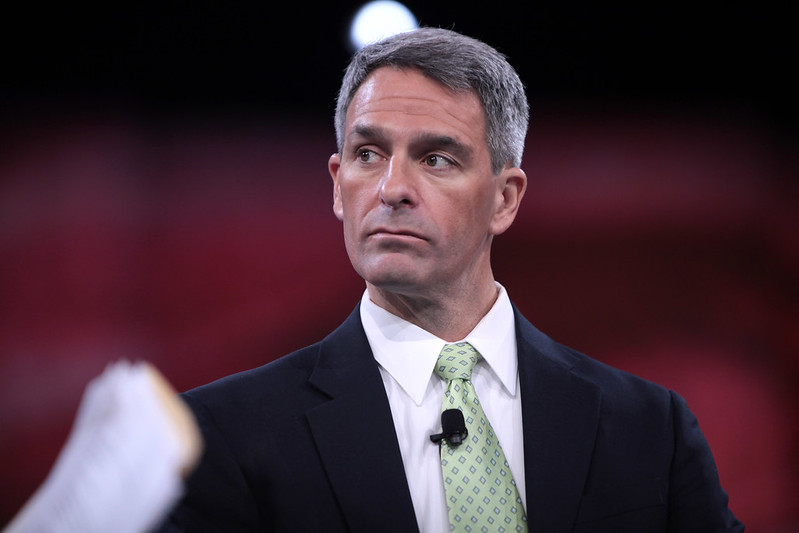

Judge Randolph Moss of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia found that Kenneth Cuccinelli’s appointment on an acting basis to lead U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services had been unlawful.

On Mar. 1, Judge Randolph Moss of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia issued a decision in L.M.-M. v. Cuccinelli—a case challenging the appointment of the acting U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Director Kenneth Cuccinelli II as unlawful under the Federal Vacancies Reform Act (FVRA), among other claims. The judge ruled that Cuccinelli’s appointment violated the FVRA.

The plaintiffs included five Honduran asylum seekers and the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (RAICES), a nonprofit organization providing legal services to refugees. USCIS had ordered the plaintiffs to be subject to expedited removal under policies put in place by Cuccinelli.

Background

The Constitution’s Appointments Clause requires that the president appoint any principal officers of the United States with the advice and consent of the Senate. This is also the default constitutional rule for inferior officers, unless Congress vests their appointment in the president, the department head or a court. Recognizing that the nomination and confirmation process can take time and that the duties fulfilled by officials in Senate-confirmed positions need continuous implementation, Congress has authorized the president to fill vacancies on a temporary basis.

The most recent statute to address this issue is the Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998 (FVRA), under which the default rule for vacancies in Senate-confirmed positions is that the “first assistant” to the office automatically becomes the acting official. The president—and only the president—can, however, do one of two other things: appoint a person confirmed by the Senate to serve as the acting official, or appoint an officer or employee of the agency “who has worked for that agency in a senior position for at least 90 of the 365 days preceding the vacancy.”

The chain of events that led to Cuccinelli’s appointment began on June 1, 2019, when USCIS Director Lee Francis Cissna resigned at the request of President Trump. At this point, Cuccinelli was a private citizen who did not hold any government position. Deputy Director Mark Koumans, Cissna’s first assistant, automatically assumed the director position pursuant to the FVRA. However, nine days later, then-acting Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security Kevin McAleenan created a new position—the USCIS principal deputy director—and appointed Cuccinelli to it. McAleenan also revised the USCIS succession order, designating this new position of the principal deputy director as “the First Assistant and most senior successor to the Director of USCIS.” Through these maneuvers, Cuccinelli became the acting USCIS director.

On July 2, 2019, after assuming his new position, Cuccinelli issued a policy that changed procedures for conducting expedited removal proceedings, which permit the Homeland Security to quickly deport certain non-citizens with limited process. If individuals subject to expedited removal indicate a desire to apply for asylum, however, an asylum officer must conduct interviews to determine whether they have “a credible fear of persecution”; if the asylum officer finds that they do, the individuals will be exempted from expedited removal proceedings. Cuccinelli’s memorandum reduced the consultation period for a credible-fear interview to one calendar day from the individual’s date of arrival at a detention facility and also stated that USCIS would deny requests for any extensions “except in the most extraordinary of circumstances.” USCIS also updated its “Credible Fear Procedures Manual” to reflect these policy changes. Additionally, the plaintiffs alleged that Cuccinelli implemented an unwritten policy change: While previously USCIS officials provided an oral, in-person legal orientation to asylum seekers, they say, Cuccinelli canceled that orientation.

The plaintiffs advanced six different claims regarding the lawfulness of these revised policies (which the court calls the “Asylum Directives”): (a) that Cuccinelli was not lawfully appointed to serve as USCIS director, (b) that the Asylum Directives are inconsistent with statutory and regulatory requirements, (c) that the Asylum Directives are arbitrary and capricious, (d) that USCIS did not comply with administrative law requirements of notice-and-comment and advanced notice, (e) that the Asylum Directives violate the Rehabilitation Act by discriminating against certain asylum seekers, and (f) that the Asylum Directives violate the First Amendment by interfering with the ability of the plaintiffs and RAICES to communicate with each other regarding the plaintiffs’ legal rights.

The court only reached the first claim, however, finding that Cuccinelli’s appointment was unlawful. In light of that determination, it set two of the Asylum Directives aside, as well as the individual plaintiffs’ deportation orders.

The Court’s Reasoning

The court first addresses whether it has standing to hear the case, concluding that it has statutory standing to hear the claims regarding the directives to reduce the consultation period and deny any extension requests, but that it does not have standing to review claims regarding the discontinuance of in-person legal orientation, because the statute states that any review must be limited to written policies. The court further finds that it has Article III standing to review the individual plaintiffs’ alleged violations of their procedural rights. Based on these conclusions, the court determines that it does not need to decide whether RAICES also has standing given that it alleged the same claims and sought the same relief.

Turning to the merits, the court finds it sufficient to resolve the case by finding that Cuccinelli was unlawfully appointed under the FVRA. Accordingly, the court holds, Cuccinelli lacked the authority to issue the Asylum Directives.

The court considers statutory text, structure and purpose, as well as history. With respect to statutory text, the only one of the three FVRA options for acting officers that arguably applies to Cuccinelli is the first-assistant provision. The court finds it does not need to consider whether the “the first-assistant default rule applies only to individuals serving as first assistants at the time the vacancy arises, or, as Defendants contend ... the default rule also applies to individuals first appointed to the position of first assistant after the vacancy in the [presidentially appointed and Senate-confirmed] office arises.” The court instead finds that “Cuccinelli’s appointment fails to comply with the FVRA for a more fundamental and clear-cut reason: He never did and never will serve in a subordinate role—that is, as an “assistant”—to any other USCIS official.”

Examining the plain meaning of assistant, the court notes that the role contemplates someone subordinate to the principal. The first assistant is then the most senior of those assistants subordinate to the principal. Cuccinelli, however, was not a first assistant, because he “was assigned the role of principal on day-one and, by design, he never has served and never will serve” subordinate to any other USCIS official. The court notes that “labels—without any substance—cannot satisfy the FVRA’s default rule under any plausible reading of the statute” (emphasis in original).

History bolsters this conclusion that Cuccinelli was not a first assistant under the FVRA. The court writes that the defendants could not identify any examples of a first assistant, appointed after a vacancy had occurred, serving in an acting capacity prior to the FVRA’s enactment.

The court then turns to the FVRA’s structure and purpose. The court finds that the defendants’ “reading of the FVRA would decimate [its] carefully crafted framework.” The FVRA was intended to allow Congress to “‘recla[im]’ its ‘Appointments Clause power.’” The defendants’ proposed approach would not serve these purposes and it would decrease presidential responsibility and accountability with respect to appointments and “vastly expand[]” the pool of individuals who could serve as acting officials.

Remedy

After finding that Cuccinelli's appointment was unlawful, the court sets aside the two Asylum Directives and the removal orders regarding the plaintiffs.

The FVRA provides that actions an unlawfully appointed officer takes “in performance of any function or duty of [the] vacant office ... shall have no force or effect” and “may not be ratified.” The plaintiffs accordingly argued that issuing the Asylum Directives was a “function” of the USCIS director’s office and therefore must be set aside. The defendants countered that the phrase “function or duty” only includes “non-delegable duties”—those that are assigned to a single official and cannot be reassigned. In the case of Homeland Security, the statute establishing the department vested all of the functions and duties in the secretary, who then delegated to the USCIS director. This means that all of Cuccinelli’s duties were delegated by the secretary, the defendants argued, and therefore the Asylum Directives could stand.

The court disagrees with the defendants’ reading of the FVRA. First, the court states, a “fallback provision” in the FVRA provides that in the case of a vacant, subcabinet office, the department head has the authority to perform the functions and duties of that office. The defendants’ reading would render this “meaningless,” the court argues, because the fallback provision would apply only in circumstances where the department head would lack statutory authority to otherwise discharge those functions. The court therefore concludes that “functions or duties of a subcabinet office must include the duties specifically assigned by statute to that office, even if the department’s organic statute generally vests the department head with all functions of the department.”

Second, the court cites a “lookback provision” of the FVRA specifying that the functions or duties of a vacant office include those established by regulations and that are “in effect at any time during the 180-day period preceding the date on which the vacancy occurs.” These provisions suggest that agencies can use their organic statutes to assign or reassign duties and these will sometimes fall within FVRA’s “functions or duties”—meaning that the phrase is not as limited as the defendants would interpret it to be.

Finally, the court also finds that the defendants’ reading of the “functions or duties” provision is at odds with the purpose of the FVRA, which Congress enacted in light of what the court refers to as the “pervasive use” of statutes that vest authority in agencies and then permit the heads of those agencies to delegate that authority. If the defendants were right, Congress would not have improved the appointment procedures it had found constitutionally inadequate.

In any event, the court also finds persuasive another argument advanced by the plaintiffs under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA): that Cuccinelli’s unlawful appointment means that the Asylum Directives were not issued “in accordance with law,” a basis for setting aside agency action under the APA. The court finds that neither of two possible saving doctrines apply in this case and, accordingly, that the two written Asylum Directives—reducing consultation time for credible fear interviews and limiting extensions—could be set aside under the APA.

The court also sets aside the credible fear determinations and expedited removal orders for the individual plaintiffs. However, it declines the plaintiffs’ request to vacate the removal orders of other asylum seekers not before the court whose cases USCIS processed under the two directives.