Taking Stock of the Islamic State

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: Experts have pointed to recent attacks and plots as proof that the Islamic State is regaining its strength. National Defense University’s Kim Cragin argues, however, that the nature of the attacks has shifted, with fewer top-down attacks and more that are inspired by the group. She also finds that law enforcement has largely managed these attacks, suggesting that while the threat is real, it is less dangerous than is often portrayed.

Daniel Byman

***

The fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime has reopened the debate on the U.S. military presence in Syria and the wider Middle East. The United States has three primary interests in Syria: averting adversaries’ potential possession of chemical weapon stockpiles, preventing an Islamic State resurgence in the region and accompanying external operations against the West, and limiting regional instability more generally. But the Islamic State’s resurgence has already begun to some extent. Islamic State fighters killed 139 people during an attack on a concert hall in Moscow, Russia, in March 2024. An Islamic State plot shut down Taylor Swift’s concert in Austria in August 2024. Then, in October, the FBI arrested an Afghan man and juvenile for planning an Election Day attack in Oklahoma City. The latter two attacks were halted due to intelligence and law enforcement investigations, but they feel a little too close for comfort.

Some critics have argued that this resurgence is the result of a reduced U.S. military presence in Syria and Iraq, and its withdrawal from Afghanistan. They believe that U.S. intelligence cannot provide sufficient indicators and warnings from a distance. Others argue that even if U.S. intelligence is up to the task, the current approach of periodic air strikes or raids conducted from “over the horizon” will not work. These critics draw on prior studies of decapitation operations and observe that they rarely have long-term effects. I have expressed my own doubts, arguing that over-the-horizon strikes might be too risky for senior decision-makers because they make it difficult to achieve the necessary pace of operations.

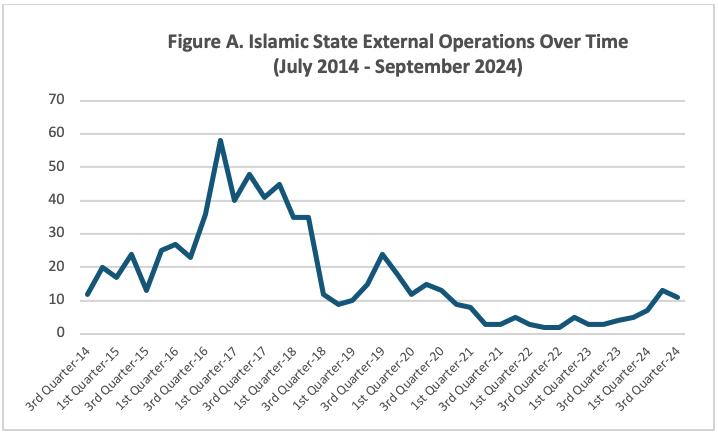

Are the critics correct? Is it impossible to execute a successful counterterrorism from afar? It has been more than three years since U.S. military forces withdrew from Afghanistan. That is enough time to derive some insight. Figure A depicts the number of successful and disrupted Islamic State external operations—defined as terrorist attacks conducted outside Syria, Iraq, or one of the Islamic State’s provinces—since June 29, 2014, when then-Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi announced the creation of a new Islamic caliphate. Over the past decade, Islamic State fighters have attempted approximately 725 external operations. Roughly half occurred between June 2016 and June 2018, but there has been a small uptick since July 2022. This uptick is what has terrorism experts concerned.

Figure A is somewhat worrisome. It suggests the Islamic State has regained some of its enthusiasm and capability to attack external targets since coalition forces announced its territorial defeat in March 2019. Yet Figure A also hides important trends. Between June 2016 and 2018, the period of most intense Islamic State external operations, approximately 61 percent of these operations originated in Syria, Iraq, or Afghanistan. Foreign fighters fought or trained in these countries and then returned home to conduct an attack. Perhaps the most well-known example is the November 2015 attack against the Stade de France, Bataclan Concert Hall, and restaurants and bars in Paris. Other external operations were enabled by Islamic State commanders in Syria, Iraq, or Afghanistan—who provided funding, guidance, or other logistical support—but were executed by local recruits. With so many external operations originating in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, it makes perfect sense that air strikes and raids would play an instrumental role in protecting the United States and its allies from attack.

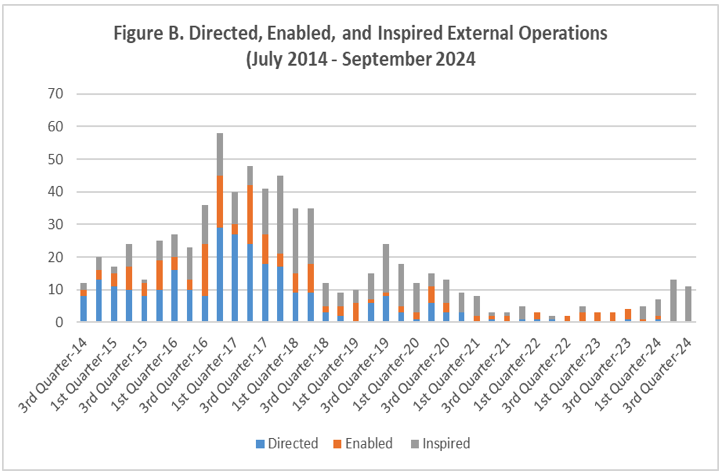

In contrast, during the recent uptick in operations between July 2022 and September 2024, only 34 percent originated in Syria, Iraq, or Afghanistan. The rest have been planned and executed by fully inspired individuals or clusters of friends without any assistance from Islamic State commanders or fighters. Figure B displays the same Islamic State external operations—successful attacks and failed plots—according to their ties to conflict zones. It indicates the relative proportions of operations directed by Islamic State leaders and commanders from within conflict zones, operations enabled by those same Islamic State leaders, and operations carried out by fully inspired individuals without direct Islamic State support. It reveals that inspired attacks account for most of the increase in external operations since July 2022.

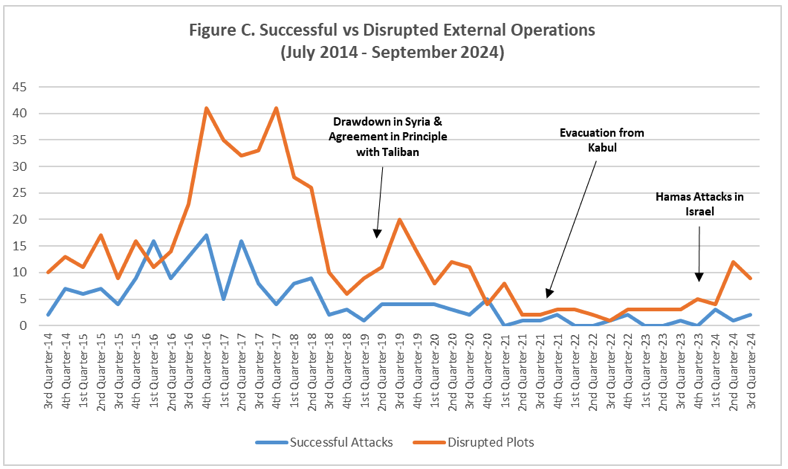

Because these external operations do not originate in Syria, Iraq, or Afghanistan, air strikes and raids in these countries are less instrumental. The responsibility falls more on federal, state, tribal, and local law enforcement, as well as international partners. So far, these actors have met the increased threat. Further, Figure C suggests that law enforcement has been able to manage the recent uptick in external operations by the Islamic State. The figure contrasts successful versus failed operations over time. The United States and its allies and partners have disrupted more external operations than Islamic State fighters have been able to execute since March 2016, with one exception, a series of attacks during the holidays in December 2022. Overall, 26 percent of the Islamic State’s external operations have been successful, while 74 percent have been disrupted. This ratio has continued since the withdrawal from Afghanistan. With the recent uptick, the United States and its allies and partners still have been able to disrupt 81 percent of the Islamic State’s external operations, despite a reduced U.S. military presence in the Middle East and South Asia.

Of course, the U.S. military retains a small counterterrorism force in the region that conducts air strikes and raids. These military operations have not stopped. Most of the air strikes over the past year have been against Iraqi and Yemeni militias that have been threatening Israel, U.S. forces, and commercial shipping in the Red Sea. Nevertheless, approximately two U.S. military air strikes and raids each quarter have targeted Islamic State commanders and fighters responsible for external operations. This suggests that, if we want to maintain a high rate of success in disrupting the Islamic State’s external operations, U.S. air strikes and raids cannot disappear entirely. But these numbers also are low enough that they probably can be sustained from a distance. Maybe not as far away as the United States—but also not from the middle of a conflict zone.

Critics might argue this analysis does not account for counterinsurgency operations against the Islamic State by local forces. It is arguable that U.S. partners’ military operations have also been important in disrupting the Islamic State’s operational capabilities. It also is likely that law enforcement agencies would not be able to manage a more significant surge in terrorist plots. That is, a ceiling of some sort might exist in how much more law enforcement agencies can accomplish without more support from the U.S. military. Nevertheless, these data contradict assertions that it will be impossible to manage a continued Islamic State resurgence from outside Syria. The U.S. military would likely need to retain an operational presence in the region. Intelligence and law enforcement postures, information-sharing, and other agreements with key regional partners would likely need to be revisited. Diplomacy would need careful thought and execution. But these efforts are simply ways to manage risk as policymakers weigh the question “should we stay or should we go?”

Note: The data presented here were derived from a database developed and maintained by the author at the National Defense University. It includes all successful external operations conducted by Islamic State operatives and sympathizers. It also includes all publicly reported disrupted plots, defined as the arrest of perpetrators who have identified the target, purchased the weapons, and made plans (e.g., logistics) to conduct the attack. It does not include arrests for money sent abroad to the Islamic State or attempted travel to Syria. The database also includes plots disrupted by the U.S. military and its allies through air strikes or raids on Islamic State external operations planners. U.S. Central Command regularly provides updates on its strikes and often names the operative targeted. If basic research through media reports and/or Islamic State propaganda confirms that these individuals helped plan a previous external operation, then this strike is counted as “disrupting” a future plot.