Tax Sanctions and Foreign Policy

Congress needs to rethink tax law so it can complement other economic tools. And Congress needs to act soon, because overreliance on other tools—financial sanctions, export controls and tariffs—threatens their long-term viability.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

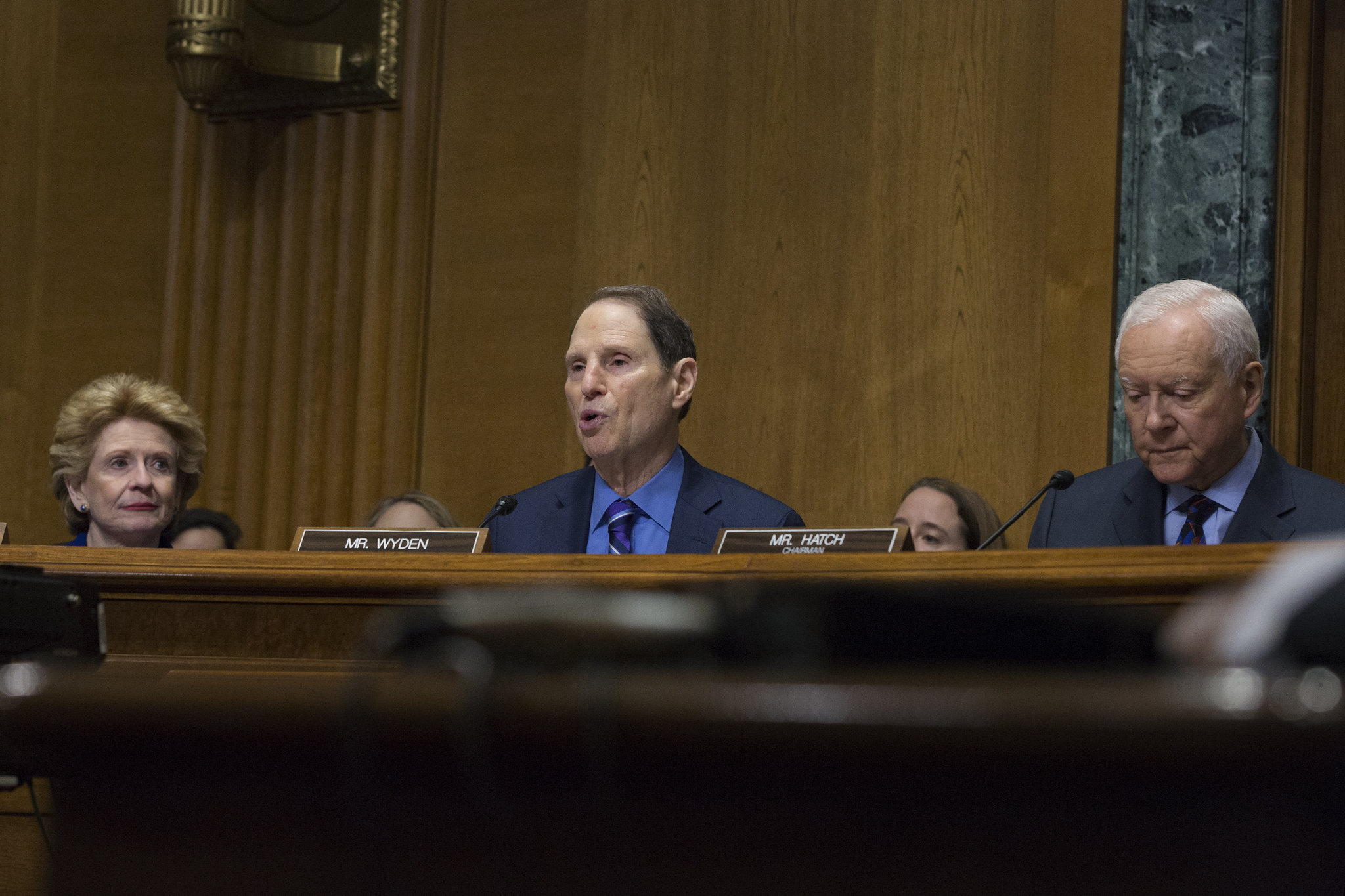

Amid the search for economic leverage over Russia, Sen. Ron Wyden has proposed utilizing tax law to deny tax credits to U.S. companies that pay Russian taxes. The proposal also limits the scope of the U.S.-Russia tax treaty, and it might enhance the pressure of financial sanctions. But Wyden’s proposal requires congressional approval—a fact that reveals how difficult it is to use tax policy as a tool of economic statecraft. Congress needs to rethink tax law so it can complement other economic tools. And Congress needs to act soon, because overreliance on other tools—financial sanctions, export controls and tariffs—threatens their long-term viability.

Income tax has historically been used as a tool of foreign policy, mostly to steer U.S. investment to strategically important countries. In the 1920s, there were incentives to invest in China; and during the Cold War, there were incentives to invest in less-developed countries. Tax treaties serve a similar function today. But there are very few rules that can be used to impose economic costs on foreign adversaries, and they reflect mostly stale foreign policy objectives. For example, U.S. multinationals that earn income in countries that support terrorism, with which the U.S. does not have diplomatic relations, or that participate in the Arab League’s boycott of Israel—a rule added in 1976—lose some of their foreign tax credits and the benefits of tax deferral for their subsidiaries. Wyden’s proposal would probably add Russia to this list of countries.

These rules are outdated. In recent research, a co-author and I found that the rules are so neglected that there was no discussion in the legislative record of how dramatic changes to the U.S. international tax rules in 2017 would affect them. As it happens, the new law probably undermined the effectiveness of those foreign policy tax rules. Next on the horizon is the recent international agreement negotiated at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development on a global minimum tax. It is unclear how implementation of the agreement will affect these provisions. The U.S. needs to develop a comprehensive and forward-looking approach to the foreign policy uses of tax law rather than reacting to specific episodes as they arise.

Congress should give the executive branch more tax tools for imposing costs on foreign targets when national security warrants it. For example, Congress could empower the president to designate a higher tax rate on U.S. investment income earned by foreign targets, or on foreign companies with U.S. branches or subsidiaries. The U.S. tax burden on income earned by U.S. multinationals in target countries could also be increased by reducing the availability of the foreign tax credit or disallowing certain deductions or by just increasing the rate on that income. There are many possibilities, but they need to be considered in advance of a crisis when they are needed. This evaluation could include their potential costs and benefits as well as their legality under the United States’ international obligations.

If these tools were available to the executive branch, it could already be ratcheting up pressure on Russian investors in U.S. stocks and securities with higher rates of withholding on payments of interest and dividends. This action would reach a wide class of individuals—beyond the extremely wealthy individuals whom the United States is already sanctioning—and yet remain targeted at relatively high-income individuals who earn capital income in the United States. Although many U.S. businesses have curtailed operations in Russia, major pharmaceutical companies continue to operate there. U.S. companies with Russian operations could be encouraged to reduce their operations through higher tax rates on the income they earn in Russia, or Congress could reduce the availability of foreign tax credits—along the lines of Sen. Wyden’s proposal. Alternatively, Congress could impose an information-reporting regime that would give U.S. policymakers data that might shed light on how the war is affecting businesses’ relationships with the Russian government and their commercial partners in Russia.

Changing tax policy will cost U.S. companies and individuals. But this is always the case when economics is used for foreign policy goals, as the recent spike in gas prices has demonstrated. The appeal of economic coercion is obvious: It’s the main alternative to the use of force. But it is not free. Using tax law could cut the overall domestic costs of economic coercion if it allows the U.S. to reduce its use of sanctions, export and import controls, and tariffs.

There are several reasons why Congress should give tax policy a greater role in foreign affairs. First, the U.S. could influence more targets than it currently does. U.S. income tax jurisdiction is the largest in the world, reaching U.S. citizens, residents and foreigners who earn income connected to the United States. Second, tax law also has built-in flexibility to modulate incentives. Taxes can be adjusted by degrees. Increasing U.S. tax rates is unlikely to trigger a large, unexpected exodus of foreign firms and individuals from the United States, and because tax incentives can be modulated, it is easy to retrench if tax sanctions begin to drive foreigners out of U.S. markets.

But perhaps most importantly, the income tax operates on different points of leverage than other economic tools and allows policymakers to use those other tools less aggressively. Financial sanctions affect the ability of targeted entities to use the U.S. financial system; export controls affect access to sensitive goods; and tariffs limit access to the U.S. market. By contrast, tax law affects all economic activity that generates U.S.-source revenues. Increasing the points of leverage on which U.S. economic coercion operates can reduce the strain on other levers of influence.

The United States uses sanctions, tariffs and other tools of economic influence more than ever before. Although the trend accelerated under former President Trump, it transcends both Democratic and Republican administrations. The United States’ increasing reliance on economic leverage raises the risk that foreigners will divest from the U.S. financial system, import market, and dollar to avoid being subject to future sanctions. Adding tax law to the foreign policy toolkit makes it possible to reduce the use of financial sanctions, tariffs and export controls, thus reducing the risk of divestment from the U.S. financial sector and dollar as a reserve currency.

Because of overuse and increased competition from alternative currencies and payment systems, the U.S. may be approaching the limits of these tools’ effectiveness. For example, the development of blockchain technology risks the creation of an alternative to the existing payment system. The emergence of growing middle classes in China and India also reduces the relative importance of the U.S. export market. And foreign currencies are becoming a larger share of global reserves. The primacy of the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency depends on the trustworthiness of the Federal Reserve and U.S. government to preserve its value. So far, U.S. assets have been the beneficiary of any flight to safety, but this should not be taken for granted. If divestment from the U.S. dollar were to happen, it could be fast and disruptive. And recent budget and macroeconomic trends in the United States may give foreigners additional reasons to rebalance their foreign currency portfolios. Higher than average inflation in the wake of the pandemic and large infrastructure and public spending legislation risks endangering the long-term stability of the U.S. dollar. All of these are reasons to be concerned about overreliance on the existing tools of economic coercion.

There are limits to how much the United States can exploit the primacy of the dollar and the centrality of the U.S. financial system to coerce foreign actors before they seek alternatives that do not leave them exposed to U.S. foreign policy imperatives. The United States needs to find alternative points of economic leverage to ensure that the existing levers do not break under the strain. The benefits of adding tax law to the toolbox are greater now than ever, and the risks of not doing so are looming.