The 9/11 Plea Deals Were the Only Way Out

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

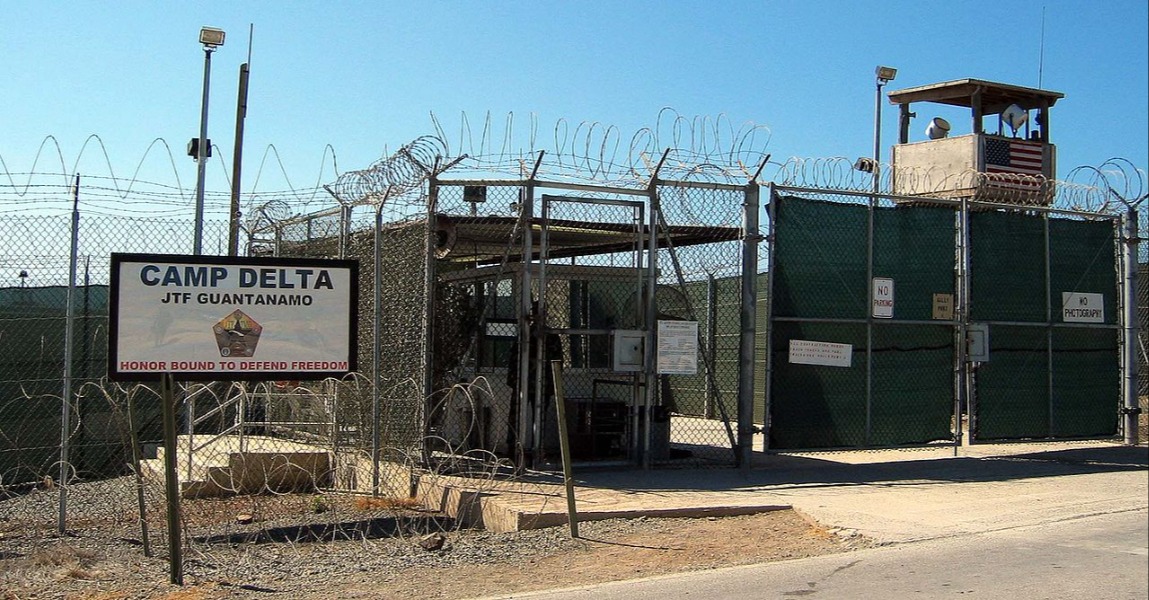

On July 31, the Department of Defense sent a letter to families of the victims of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. Three defendants in the Guantanamo military commissions case Khalid Shaikh Mohammed v. United States—the so-called 9/11 Case—had entered into plea agreements (pretrial agreements, or PTAs, as they’re known in the commissions). The news would “understandably and appropriately elicit intense emotion” and “be met with mixed emotions,” the letter said.

The next day, the parties entered the signed agreements with the court under seal.

The day after that, on Aug. 2, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin issued a terse, two-paragraph order withdrawing from all three agreements. “[I]n light of the significance of the decision to enter into pre-trial agreements,” he explained “responsibility for such a decision should rest with me.”

And just like that, the brief hope that these cases could finally be resolved was extinguished.

So what happened? And what does it mean? We can venture a partial answer to the former question; we know bits and pieces through reporting and litigation documents. The latter question has a straightforward answer: If the PTAs are terminated, it means these cases will not be resolved. They will never get to trial; the legal issues are too labyrinthine to fully litigate in the foreseeable future, and there is no guarantee that the defendants will remain triable (all have health problems, and one of the original five defendants was deemed incompetent to stand trial last year). Even if the cases did get to trial, it’s not inevitable that the prosecution will be able to prove its case; evidence may become unavailable as memories fade and witnesses die, and some evidence may be suppressed due to the “original sin” of the defendants’ torture. Even if prosecutors did prove their case, and even if the defendants were given the death penalty, the case would go up on automatic appeal under 10 U.S.C. § 950c, and the defense would rightly appeal beyond that.

What makes Secretary Austin’s order so destructive is that guilty pleas are the only way out. They represent the sole possibility for 9/11 families to see some semblance of the public reckoning a trial is meant to provide. The defense, the prosecutors, and the convening authority all recognize this. That’s why they made these deals. But Austin chose to ignore this reality—just the latest in a long tradition of political leaders determined to avoid the choices necessary to bring this case to an end.

Austin’s order gave the impression that he was somehow surprised to learn of the guilty pleas. He could not have been.

It was no secret that the parties had been negotiating. Talks had been underway for more than two years. In March 2022, the New York Times reported that prosecutors had reached out to the defendants to propose a deal and negotiations were underway. The Guantanamo Military Commissions convening authority would have to approve any deal the prosecutors and defendants reached. Unlike in civilian court, the defendants’ counterparty to a plea agreement is not the prosecution, but the convening authority. There are other important procedural differences between PTAs and civilian plea agreements, but the foundation is the same: Defendants admit their guilt and forfeit their right to trial and appeal in exchange for certain terms, often including an agreed-upon length of the sentence.

In October, the judge issued an order canceling previously scheduled hearings because plea negotiations had reached the point where the prosecutors were seeking necessary approval from policymakers. As the judge explained, “certain aspects of the plea negotiations involve ‘policy principles’ which are beyond the [convening authority (CA)] to approve and which are therefore pending decision by United States policy makers.”

A few months later, in January 2023, the PTA negotiations had proceeded so far that reporting suggested that it was being held up not by whether agreements were possible in principle, but by uncertainty about who would make the agreements on behalf of the government. The White House declined to weigh in and deferred to the Defense Department instead—but, according to the New York Times, officials there were “said to be uncertain they have the right to decide on a course of action with such major implications.”

By Sept. 6, 2023, it was official: The Biden administration had declined to accept the terms of the “policy principles” that it would have to approve to allow the deals to go forward under the terms the defendants had requested. The prosecutors’ notice to the court provided no explanation as to the basis for the administration’s decision. It simply relayed the message: “the Administration declines to accept the terms of the proposed joint policy principles offered by the accused in the military commissions case, United States v. Mohammed, et al.” It’s plausible the prosecutors themselves had not received any explanation either.

What we don’t know—and what seems a crucial question—is whether the newly designated convening authority had been given an explanation. Secretary Austin had designated her only one week prior to the administration’s rejection of the policy principles. Either way, it’s clear that even during a moment in which the 9/11 Case plea agreements were top-of-mind for the administration—including her boss, Austin—the convening authority was not instructed to cease negotiations on a possible plea. (If she had been given such an instruction and later signed the PTAs anyway, surely Austin would have fired her in his Aug. 2 order; instead, he merely removed her authority as to the three defendants with whom she had signed the PTAs.)

On May 1, 2024, prosecutors informed the judge in open court that both the prosecution team and the convening authority remained interested in reaching agreements. On June 10, the judge issued an order setting the next session of hearings for July 15.

The hearings seem to have opened relatively uneventfully. The judge gave an overview of the four weeks of proceedings to come, which would include oral argument and witness testimony, including from a psychologist who oversaw the waterboarding of Khalid Shaikh Mohammed. Proceedings would continue to plod along; litigation had been ongoing throughout the years of negotiations, and there was a lot to do.

But on July 31, the Defense Department issued a press release announcing the PTAs. A flurry of reporting followed. Op-eds were written celebrating and decrying the deals. Members of Congress issued statements both for and against them. Family members of Sept. 11 victims, too, were split—some supported the deals, others were outraged.

The lawyers who had negotiated the deals showed up in court the next day as planned. The lead prosecutor formally announced the PTAs. The judge agreed to keep the agreements under seal until a jury was empaneled as part of the sentencing proceedings. The day after that, on Aug. 2, the lawyers returned to court for a closed session. News of Secretary Austin’s order came at about 8:00 that evening, summarily and without explanation reversing the past two years of the parties’ work.

Something significant had shifted to allow the deals to finally come together this summer.

The prosecutors agreed to remove the death penalty as a possible sentence—but that was a concession they had already made in previous rounds of negotiations. The defendants had been asking for years for the deals to include assurances of certain conditions of confinement like treatment for torture-related trauma and avoiding solitary confinement. The defendants reportedly gave up this demand for these deals. But there’s a lot we don’t know about what else is in the PTAs. So it’s impossible to know exactly what convinced all the parties to agree now, after all these years.

What we do know is that the PTAs had established a plan for working toward resolution of the case. The first crucial steps were complete: The prosecutors and defense negotiated the terms of the PTAs and reached consensus. The convening authority, in her discretion as provided by law, approved and signed them on behalf of the U.S. government. The parties filed the sealed PTAs with the military judge.

The end was in sight, though still a long way off. The judge had not yet performed the necessary colloquies under Rule of Military Commissions (RMC) 910(d) to ensure that the guilty pleas were voluntary, willing, and uncoerced. And the judge had not yet made the inquiry under RMC 910(e) to ensure the PTAs were accurate—a process that requires the judge to question each defendant individually to establish the factual basis of the plea. That may have been scheduled for next week.

Sentencing would have come next. Unlike in the civilian criminal justice system, sentencing in the military commissions is a fully contested proceeding. It is effectively a mini-trial. Both sides make arguments to the panel (the military commissions equivalent of a jury)—not to convince it of guilt, but to make their case for an appropriate sentence. By law, the panel cannot be made aware of the fact of the agreement or its terms; the sentence it renders does not take into account what prosecutors, the convening authority, and the defendants have agreed upon.

The military commissions system effectively starts sentencing of guilty pleas from a blank slate. Because the panel has not sat through a lengthy trial and adjudicated the defendants’ guilt, the parties can start from scratch in building a narrative about who the defendants are and what punishment they deserve. To do that, both sides are entitled to introduce evidence and call witnesses to testify. The letter to 9/11 families made clear that such witness testimony was envisioned in this case: “During the sentencing hearings in this case, there may be an opportunity for a member of your family to testify about the impact the Sept. 11 attacks have had on you and your loved ones.” It could have looked a lot like the sentencing proceeding that occurred just last month in the case of Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi.

The PTAs reportedly contained another term that would have made sentencing even more like a regular trial: The defendants were required to “respond to questions submitted by [9/11 victims’ family members] regarding their roles and reasons for conducting the September 11 attacks.” It was an opportunity to establish the facts, to publicly account for what had happened, to inquire about motive—all the key features of a trial.

The hearings would have happened no earlier than summer 2025, according to the letter. In the military commissions system, even after sentencing proceedings are completed and the judge issues the “adjudged sentence,” the case is not closed. It goes to the convening authority’s legal adviser for a recommendation, and then to the convening authority herself, who must “take action” pursuant to RMC 1007 before the sentence can begin.

The path to resolution would have been long even with PTAs. But the path was clearly there. And along the way, there would have been opportunities to seek the truth of what had happened, to allow victims to confront the defendants with how it affected them, to hear from the defendants about how they were treated in detention. It all would have happened in front of a jury that would have passed judgment in the form of a sentence. It was a path, in other words, that could have accomplished much of what we expect from a trial.

Now that Secretary Austin has withdrawn from the PTAs, the path has almost certainly disappeared.

It’s hard to recognize just how true that is, because it’s hard to keep track of this case. Charges were originally brought in the military commissions in 2008, then dropped in 2010 as part of then-President Obama’s effort to transfer the defendants to New York to stand trial in federal court, then reopened after Congress passed legislation to forbid that trial from happening. Trump’s attorney general, William Barr, also explored the possibility of bringing Guantanamo defendants to federal court to be tried, but congressional Republicans refused to lift the legislation’s ban on transferring detainees to the United States.

There had been efforts to reach a plea on multiple other occasions over the years. In 2017, the then-convening authority was exploring PTAs until he was abruptly fired, along with his legal adviser. That was about a week after then-President Trump signed an executive order calling for GTMO to remain open. In 2019, one of the defendants had offered to help the plaintiffs in a suit against the Saudi government for its role in the Sept. 11 attacks in exchange for being spared the death penalty. All of these efforts failed—until the round that started in 2022.

As of Aug. 2, the date of Secretary Austin’s order, the 9/11 Case docket had 13,363 entries. Several of the ones that seem most likely to shed light on the key outstanding issues are still listed as “under security review,” despite a requirement that they be made public—in redacted form as appropriate—within 15 business days of the document’s filing. For example, AE819(AAA), al-Baluchi’s “Motion to Preserve Evidentiary Value of Camp 7,” was filed in April 2021, but it remains unavailable on the docket. What is the evidentiary value of the notorious prison, which has been described as “the base’s most clandestine of lockups,” and for what purpose is al-Baluchi seeking it? No way to know. The placeholder document cheerfully advises you to “check back often.” Seemingly mundane documents are occasionally and inexplicably under review for weeks at a time, too—like the original scheduling order for the hearings that just concluded, even though multiple amendments to it are already publicly available.

Even the most dedicated researcher trying to understand what is holding up this case would be helpless were it not for the indefatigable Carol Rosenberg, who has been reporting on Guantanamo since the first detainees arrived in 2002 and is often the only journalist on the base. But Rosenberg’s task is to report with a restricted word count fitting for a major newspaper, not to analyze the intricacies of the legal filings. So the outside legal observer could be forgiven for being unaware of just how far from resolution these cases are in the absence of PTAs. Unaware, for example, that it was only a few weeks ago that the parties submitted briefs in response to the military judge’s order to explain, among other things, “[w]hat authority allows the Prosecution to invoke the ‘national security privilege’ to completely preclude the Defense from asking specific questions or making specific oral arguments” or “using classified information it has received in discovery in a closed session.” (That’s right, more than a decade after this case began, we’re still not quite sure what “national security privilege” means.)

Unaware that one of the reasons this matters seems to relate to the parties’ litigation over what information the prosecution may withhold from discovery—discovery defendants appear to be seeking for the purposes of learning about interrogation(s) to which they were subjected in 2007, which in turn seem to relate to outstanding motions to suppress certain evidence about their statements made during those interrogations on the grounds that they were tainted by torture. (In a different case, the military judge just suppressed that defendant’s statements from the same time period. The ruling is currently on appeal.) In the 9/11 Case, prosecutors reportedly told the court that these statements are the most important part of their case.

Even after the military judge rules on all the ancillary litigation and reaches the question of whether to suppress the statements—a process that will take many more years—the losing party will undoubtedly bring that decision up on appeal to the Court of Military Commissions Review. And the party that loses there will appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. And the party that loses there will petition for certiorari to the Supreme Court. Eventually it will wind its way back to the military commission. What if, after all that, the statements are indeed suppressed—would the prosecutors even have sufficient evidence to prove their case at this theoretical trial?

But that’s only one of the motions at play in the 9/11 Case. The same process could happen with any number of other issues currently being litigated. Again, it’s hard to sort out exactly what those are. Even with the benefit of reporting from Rosenberg and other journalists, even with a docket that is at least somewhat public, it’s difficult to pinpoint all the legal issues. The filings and transcripts are full of redactions, many of the more than 13,000 documents are sealed or classified, many hearings are closed.

After 13 years of litigation, there’s just too much for anyone—commentators, politicians, even the secretary of defense—to wrap their head around. No one knows how to bring these cases to resolution. No one claims to have an end in sight.

Except for the parties who have been living through it. They know exactly what is possible and what is not. And they’re the ones who had made the deal.