The Difficulties of Defining “Secure-by-Design”

New survey findings and efforts to identify the most impactful security controls underscore the need for an empirical approach to defining—and promoting—security-by-design.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Security-by-design is not a new idea. By some reckoning, it dates back to the 1970s. Various companies, including Microsoft through its Security Development Lifecycle, have tried to implement security-by-design with varying degrees of success during the preceding decades.

The March 2023 release of the Biden administration’s new National Cybersecurity Strategy called on Congress to promote the adoption of security-by-design principles, which the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency defines as a product in which “the security of the customers is a core business requirement,” not an afterthought or technical feature. The current notion of security-by-design builds off of several related initiatives, including zero trust security.

In May 2021, the Biden administration called for the adoption of zero trust security by the federal government. As one of the authors has argued, trust in the context of computer networks refers to systems that allow people or other computers access with little or no verification of who they are and whether they are authorized to have access. Zero trust, by contrast, is a security model that takes for granted that threats are omnipresent inside and outside networks. Zero trust instead relies on continuous verification via information from multiple sources. In doing so, this approach assumes the inevitability of successful cyberattack. Instead of focusing exclusively on preventing breaches, zero trust security ensures that damage is limited and that the system is resilient and can recover quickly.

However, there are significant barriers to achieving zero trust architecture, including legacy systems and infrastructure. Security-by-design can help ensure that technical debt doesn’t continue to mount, such as by incentivizing hardware innovations. Related supply chain tracking and transparency programs such as the Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) also help promote the layered cyber deterrence called for by the Cyberspace Solarium Commission.

But the core goal of making cybersecurity central to decision-making that lies at the heart of security-by-design remains elusive, as seen in findings from a 2023 state-level survey. We use key takeaways from this survey to illustrate this point and to highlight on-the-ground realities in the context of cyber operations. More work is needed to identify the most impactful security controls, which our team has attempted to do below while also highlighting the importance of a similar evidence-based approach to defining a safe harbor regime to incentivize security-by-design techniques.

Findings From State-Level Surveys

One way to both take stock of the status quo and consider what form a safe harbor regime for software liability should take is to define how far the industry is away from a more robust and accountable software ecosystem that puts security at the center of its decision-making.

A recently undertaken survey of Indiana organizations sought to understand how cybersecurity attitudes and practices have changed since the coronavirus pandemic began. (Several of us conducted this survey in conjunction with the Indiana Executive Council on Cybersecurity in summer 2023 as a follow-up to a prior survey effort in 2020.) There were 140 complete responses to this survey. Although selection into our respondent pool is nonrandom and thus not fully representative, it can still be viewed as an important exploratory exercise in providing context for what form a safe harbor for software security should take.

To begin, the organizations that responded to this survey were concerned about the risks of a cybersecurity incident, with 55 percent of respondents indicating they were very concerned and 41 percent of respondents indicating they were somewhat concerned. This level of concern has increased or stayed the same over time: 47 percent of respondents indicated their organization was as concerned about the risk of a cyber incident as they were in spring 2021, while 48 percent indicated that they were more or much more concerned.

Responding organizations most commonly specified that their organization was concerned about phishing (81 percent), ransomware (78 percent), and malware (76 percent). These types of hacks impose substantial economic costs: In a recent working paper with colleagues, one of us reported that a 1 percent increase in county-level cyberattacks covered by the media leads to an increase in offering yields ranging from 3.7 to 5.9 basis points, depending on the level of attack exposure. Evaluating these estimates at the average annual issuance of $235 million per county implies $13 million in additional annual interest costs per county, which inevitably affects local firms.

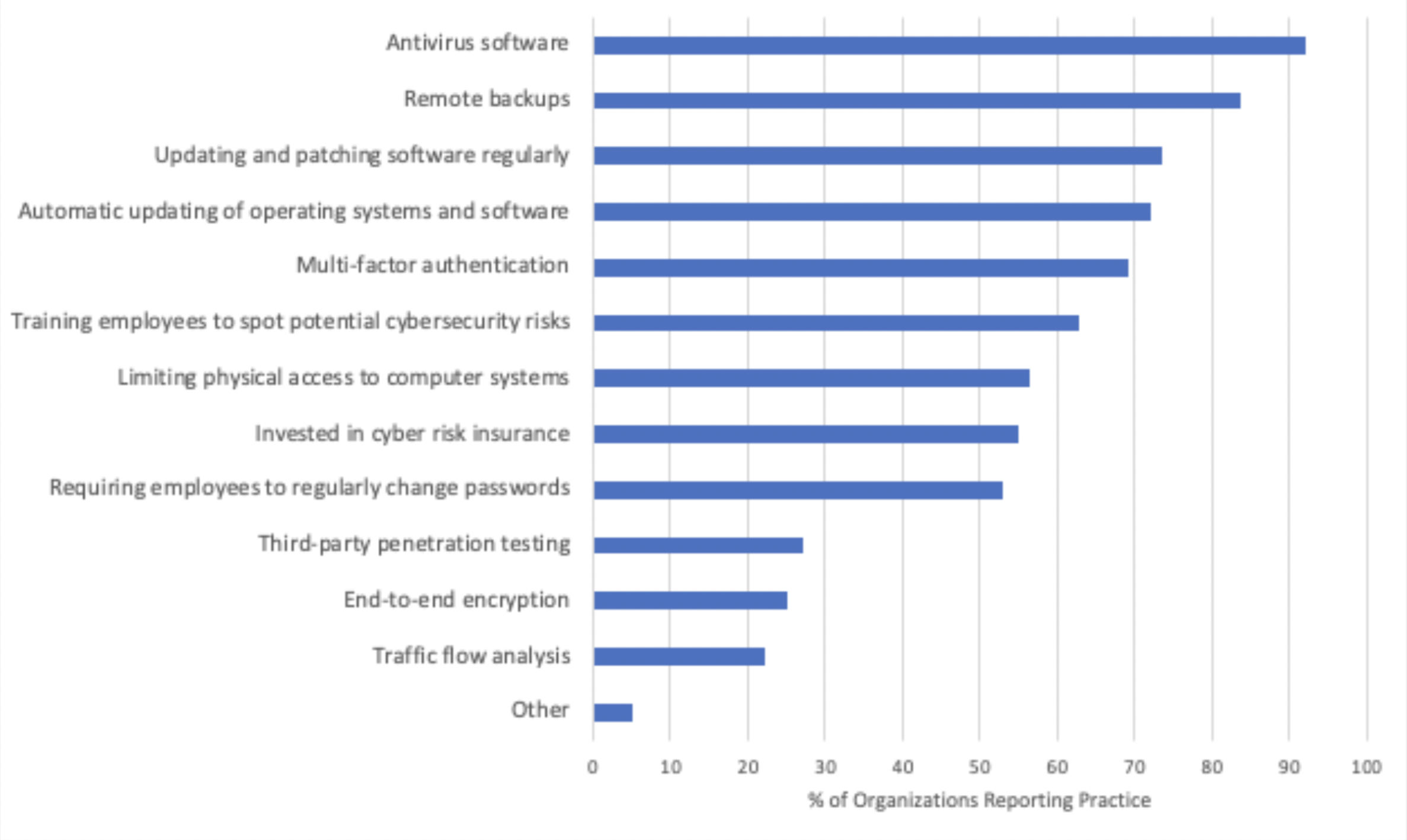

The organizations that responded indicated that they engaged in a wide variety of cyber risk mitigation practices (see Figure 1). On average, entities reported that they undertook seven risk mitigation practices of the 12 presented, with the use of antivirus software, remote backups, and regular software patching being the most commonly adopted such practices. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) reported using fewer practices on average than larger organizations (6.2 practices for SMEs compared with 8.2 for large entities). In particular, those in large organizations were more likely than those from SMEs to report use of multifactor authentication (81 percent compared with 62 percent), end-to-end encryption (37 percent compared with 17 percent), training employees to spot potential cybersecurity risks (79 percent compared with 53 percent), and automated updating of operating systems and software (84 percent compared with 66 percent).

Figure 1. Risk mitigation practices currently used by organizations.

Respondents were also asked about how their organization proactively planned to manage potential cyber threats facing their organizations. Thirty-four percent reported their organization had revised and updated their incident response plan, 33 percent reported their organization consulted news reports, 21 percent reported their organization joined an information sharing group such as an Information Sharing and Analysis Center (ISAC), and 21 percent indicated that their organization relied on government data such as that from the United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT). Thirty-five percent reported that their organization used an externally developed framework to guide their cybersecurity decision-making, while 42 percent indicated that their organization did not use a framework for this purpose, and 22 percent indicated that they were unsure. Cybersecurity framework use was reported more often among large organizations than SMEs (49 percent compared with 26 percent). Respondents who indicated their organization used an external framework most commonly reported use of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework.

The push for proactive cybersecurity underlines the pressing need to address the growing cyber threat landscape. Despite strides by tech giants like Microsoft, the data from Indiana organizations reflects a broader concern, especially among small and medium-sized enterprises. The disparity in cybersecurity practices between large organizations and SMEs is a critical gap that needs addressing. Moving from a “Patch Tuesday mentality” to a security-centric software ecosystem is a collective endeavor. It demands concerted efforts from policymakers, the tech industry, and end users to foster a safer digital environment.

A Model for Building Evidence-Based Standards

The Indiana University Center for Applied Cybersecurity Research (CACR) has been conducting interdisciplinary cybersecurity research and development since 2003. These years of exposure to a wide range of critical infrastructure operators, all of whom struggle in some way or another with cybersecurity, have sensitized us to the increasing severity and urgency of the cybersecurity problem, as well as the potential for that urgency to lead to insufficiently informed policy and practical decisions. The standards and guidance in the cybersecurity operations world generally lack (a) an explicit, proven evidentiary basis, (b) the structure needed to meaningfully implement and measure their requirements, and (c) an appreciation of the nontechnical aspects of cybersecurity, such as governance, resources, and mission alignment. There’s no need to repeat these mistakes when it comes to security-by-design standards. Emerging research initiatives (discussed below) can be a model for how to build reasonable, evidence-based standards. As stakeholders and decision-makers press forward into the intersection of liability and security-by-design, we urge the following.

Basing Standards on Evidence of What Really Makes a Difference

Precious little research exists about what cybersecurity practices and controls are truly most effective at preventing or limiting the impact of cyberattacks. There’s even less research on what are the most impactful and cost-effective controls. Organizations like MIT’s Internet Policy Research Initiative and CACR are part of a start at cobbling together a practical, open research agenda in this space. Meanwhile, cybersecurity standards and guidance-making bodies continue to produce long lists of must-do controls with little to no explanation of how those controls were selected, much less any evidence to support those as effective.

In the cybersecurity operations context, CACR has begun to fill the evidence-based practice gap by clawing together and analyzing any systematic studies we can find. For example, in CACR’s work to build Cybertrack, the State of Indiana’s local government cybersecurity assessment program, we knew we needed to build an efficient assessment methodology structured around a doable, meaningful standard. To do that, we could not reasonably pick up any “off the shelf” cybersecurity control standard and apply it whole hog. Even the CIS Controls, which are well prioritized and well constructed overall, would present a vast and costly (read: crushing) amount of work for most local government organizations to implement.

To get to sanity, we conducted research to identify an evidence-based, highly prioritized subset of the CIS Controls’ Safeguards. We set out to identify “gold standard” systematic studies whose results point to a small set of proven high-power controls. To meet this gold standard, we had to develop confidence in the validity of the methodology used in each candidate source. As such, we considered and eliminated a number of sources (including many government sources) that lacked any publicly available documentation of their methodology. We found three studies that qualified: the CIS Community Defense Model (version 2.0), the Microsoft Digital Defense Report, and the Australian Signals Directorate’s Essential Eight. Notably, each of these three used a different methodology. We mapped the identified controls to the appropriate CIS Safeguards and scored them: Safeguards received a score for each appearance in a gold standard study. Thus, those safeguards that appear in more gold standard studies received a higher score.

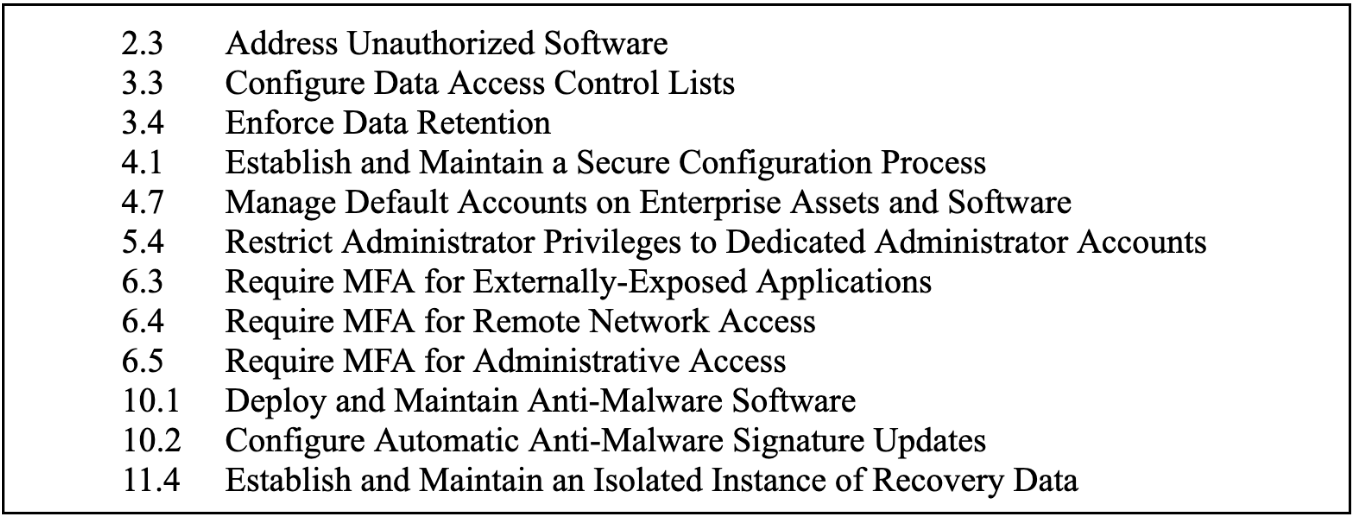

This research resulted in an evidence-based, prioritized list of the CIS Safeguards, with 12 safeguards making up the top-scoring group that are now the major focus of the tactical-level standard for the Cybertrack assessment. We validated this ranking and highest-scoring “Transformative Twelve” safeguards via independent Indiana University and Purdue University subject matter expert analysis, confirmed the very high presence of these safeguards in other standards (for example, NIST’s), compared them to the results of a recent North Carolina State study that followed a methodology similar to the CIS Community Defense Model (version 2.0), and ultimately conducted a detailed reanalysis.

As a result, we have high confidence that the core set of specific controls we’re assessing are truly fundamental and impactful (see Table 1). This is not to say that these are the only controls worth implementing. Moreover, much-needed future research may result in a somewhat different top-scoring group. However, in the context of a cybersecurity landscape where some “standards” include hundreds of controls, and most lack prioritization or evidentiary grounding, we see building real confidence in any subset as a victory for practicality.

Table 1. The Transformative Twelve

* The numbering system corresponds to specific Safeguards from the CIS Controls v8.0. |

Evidence-based efforts like the research that revealed the Transformative Twelve should be a model for efforts to determine reasonable standards for security-by-design: What really matters most when it comes to security-by-design? What makes the biggest difference in security outcomes? If we can identify these things, then we can confidently build law and policy around them. For instance, do we know whether it is more effective (in terms of the ultimate frequency and impact of cyberattacks) to train software developers in secure coding practices or simply to require organizations to delete the unused code that is often left in place and delivered (along with many vulnerabilities) to consumers? We know from our colleague Susan Sons’s research that cleaning up code can remove a ton of vulnerabilities from code. But what can we say about the comparative difference it makes and the relative costs of prioritizing one seemingly-good practice over another? These are the types of questions that would-be security-by-design regulators need to answer.

Taking Into Account the Full Breadth of Cybersecurity

Cybersecurity, and certainly security-by-design, is far more than a technical problem. The Trusted CI experience has highlighted the importance of the nontechnical aspects of cybersecurity. The organizations we engaged with lacked the money, personnel time, and leadership support to even begin implementing many cybersecurity controls. This experience led us to develop the Trusted CI Framework, a minimum standard for cybersecurity programs. The Trusted CI Framework consists of 16 “Musts” and is derived from the organizational blockers we consistently saw impede effective cybersecurity programs: lack of resources, poor governance, ad hoc control selection, and weak mission alignment. By focusing on programmatic fundamentals, organizations can turn these blockers into enablers for cybersecurity.

The programmatic requirements in the Trusted CI Framework are straightforward and may be dismissed as common sense. But our experience is that many organizations have not put in place the basic programmatics necessary to enable cybersecurity. These include elements like “Organizations must establish and maintain a cybersecurity budget” and “Organizations must establish a lead role with responsibility to advise and provide services to the organization on cybersecurity matters.” While straightforward, these elements are extremely impactful, and many organizations are not doing them. As organizations implement these fundamentals, we see their ability to successfully implement more tactical and technical cybersecurity practices increase.

Perhaps more importantly, by moving out of the technical weeds and focusing on programmatics, organizations can more effectively engage their leadership in cybersecurity decision-making. Technical security controls are often uninteresting or actively disengaging to leadership and can alienate those leadership roles from effectively engaging in important cybersecurity decision-making.

Programmatic requirements for security-by-design are unlikely to differ meaningfully from basic cybersecurity programmatics. Indeed, many programmatic requirements benefit from starting early and would be excellent candidates to consider when crafting security-by-design rules and standards. For example, clearly laying out roles and responsibilities for risk acceptance (Must 6), designating a lead security-by-design person (Must 7), and conducting evaluations and taking action based on those evaluations (Must 10) are all meaningful steps that organizations can take as part of their security-by-design efforts.

Designing Standards With Measurement in Mind

Most cybersecurity standards and guidance aren’t created with measurement in mind. On its face, the typical cybersecurity control description can seem straightforward: For example, CIS 4.1, “Establish and Maintain a Secure Configuration Process,” is widely considered to be one of the most fundamental and powerful controls. But what exactly is required to have established a “secure configuration process”? CIS, and indeed nearly every standard-producing organization, provides additional detail on what they think each control means, but this additional information rarely, if ever, rises to the level of clarity we would expect from a legal requirement. Is it sufficient to have any process, or are there other, unstated substantive requirements? Or what if your secure configuration process is applied almost everywhere in your organization, but there are a few categories of assets that have proved tricky to reach?

These distinctions are less problematic when the control’s primary purpose is to guide behavior. Many cybersecurity practitioners have a reasonable understanding of the shortcomings and nuances of their own systems, and these controls can provide excellent directional guidance on how to prioritize generally. But when a control becomes a deciding factor on questions of liability, the exact details become supremely important, and existing standards do not provide the level of clarity needed.

CACR’s experience is that even highly experienced cybersecurity experts will disagree on the exact interpretation of individual controls when applied as a measurement standard to common factual settings. And these disagreements become much more frequent when the control is being applied to less conventional organizations or environments. For our teams to consistently evaluate local governments for the Cybertrack project, we needed to develop detailed internal “rubrics,” written much like statutes, that clearly establish what it takes to honestly say that an organization “is implementing” that control. We broke down each control into a series of elements, like a criminal statute, with each element needing to be met for the local government to be considered implementing that control. These rubrics are not meant to be the authoritative interpretation: They are a product of our need to evaluate against a clear, consistent standard.

CACR is not alone in this challenge. Arguably the largest, most visible attempt to conduct widespread cybersecurity assessments is the Department of Defense’s Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC). Despite being built around NIST SP 800-171, a preexisting and widely known standard (itself derived from the even longer standing FISMA Moderate Confidentiality controls found in NIST SP 800-53), the actual rollout of CMMC has proved far more complex and challenging than the designers anticipated. Despite CMMC being announced in 2019 with an ambitious 2020 start date, its timeline has continued to be pushed back in the face of practical challenges, many of which relate to conducting cybersecurity assessments at scale.

Any requirements for security-by-design should be designed with measurement as a primary design criteria. This may necessitate narrowing the scope of requirements (for example, requiring multifactor authentication for administrative accounts that are connected to the internet); focusing on simple programmatic requirements (for example, requiring a designated “security-by-design” champion); or explicitly incorporating some legal language, with the understanding that courts may ultimately have to unpack what that language means on a case-by-case basis. For instance, in Cybertrack, we established an element requiring “no significant gaps” in the implementation of each control. This element addresses the practical difficulty of applying controls everywhere, while avoiding a more narrow focus to “everywhere that really matters.”

* * *

Further research evaluating what best practices are the most impactful in improving security outcomes is needed prior to defining a safe harbor regime. Security-by-design is an excellent goal to strive for, but if those who influence and are responsible for setting requirements rush into it, our society will simply end up with another compliance regime that drives organizations toward checklists rather than incentivizing security outcomes. Policymakers can help in this process by working with academia, labs, and civil society to discover the equivalent of the Transformative Twelve for software. A small evidence-based set of the most-proven practices—including the organizational and strategic as well as the technical and tactical—will ensure its doability, make implementation assessment more practical and scalable, and build trust among all the stakeholders impacted.

-(1)-(1).png?sfvrsn=1bc11cd_4)

_-_flickr_-_the_central_intelligence_agency_(2).jpeg?sfvrsn=c1fa09a8_5)