The Evolving Threat From Terrorist Drones in Africa

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: Drones are changing conflicts around the world, and terrorist groups are among their eager users. Africa is no exception to this trend. Rueben Dass of the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research in Singapore examines how different African terrorist groups have used drones, arguing that they are primarily for surveillance and propaganda for now, but that their use may broaden in the years to come.

Daniel Byman

***

Since the fall of the Islamic State’s last stronghold in Baghouz, Syria, in March 2019, the epicenter of jihadi terrorism has shifted from the Middle East to Africa. As with terrorist groups elsewhere, those in Africa have incorporated innovative technologies into their operations. These groups are increasingly using drones on and off the battlefield, creating a new dimension of the threat in the region.

What Are Terrorists Doing with Drones?

Terrorist use of drones can be divided into two categories: active-offensive uses (for example, to deliver explosives to a target) and passive-defensive (for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, and filming propaganda). In Africa, terrorist use of drones has been passive-defensive. The types of drones used by terrorist groups in most cases are either unclear or unreported, but evidence from propaganda footage and other sources suggests these tend to be commercial quadcopters.

Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR)

In 2020, al-Shabaab used drones to record and coordinate an attack on a U.S. military base in Manda, Kenya. U.S. government officials have confirmed that al-Shabaab uses drones in their operations, and the U.N. Security Council (UNSC) noted a “prolific use” of drones by the group. In May 2020, Ahlu-Sunnah wal Ja’maa (ASWJ), an Islamic State affiliate in Mozambique, used drones to identify targets in the Mocimboa de Praia attacks. The following year, ASWJ used drones again for ISR in its attack on Palma. Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) has also used drones for ISR to aid in their attacks. In July 2022, in the town of Gubio, Nigeria, ISWAP used a surveillance drone to survey the location of a Nigerian military convoy before ambushing them. A month later, Islamic State Greater Sahara (ISGS) also carried out a drone-assisted attack on security forces in Mali.

Military forces have begun to notice an increased use of terrorist drones. A July 2022 U.N. Security Council report noted that the Mozambican army had neutralized several drone formations that they suspected were gathering intelligence on local security forces’ positions. In February 2023, Mozambican forces shot down another two ASWJ surveillance drones. Mini-drones were also detected over a military base in the Shabelle region of Somalia.

Propaganda Videography

Apart from ISR, terrorist groups have used drones to film propaganda videos. The use of drones not only adds cinematic value to the videos but also is a symbol of airpower, status, and technological prowess that could aid recruitment. ISWAP released propaganda videos in January and April 2022 showcasing aerial footage that was likely shot using a commercial quadcopter drone. In November 2022, Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP) also released a propaganda video shot using drones, and Mali-based al-Qaeda affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa al-Muslimeen (JNIM) has made similar drone videos.

Although terrorist groups in Africa have not used drones offensively thus far, experts have noted that it is only a matter of time before they begin doing so. In the past, the Islamic State successfully weaponized commercial drones, such as DJI quadcopters, for use in attacks in Iraq and Syria. These drones were used to drop explosives on security forces, direct suicide bombers to targets, perform ISR, and film propaganda. The Institute for Security Studies, an African think tank, recently reported that ISWAP is testing delivery drones to carry explosives for use in attacks, indicating that the group is attempting to mimic the Islamic State’s drone use in the Middle East.

Three Types of Drone Access

In the case of Africa, there are three enablers of drone use that require attention. The first is the proliferation and commercialization of drone technology. The hobbyist drone market is growing rapidly in Africa, with global sales projected to grow from $14 billion in 2018 to $43 billion in 2024. The low cost and easy availability of hobbyist drones has made them an instrument of choice for terrorist groups in Africa.

Drone security experts Kerry Chávez and Ori Swed have noted that the advancing autonomy and avionics in drone systems, such as improved obstacle avoidance and vertical takeoff and landing capabilities, are making civilian drone operations even easier. While terrorist groups may be unable to overcome the financial and technical barriers to obtaining military drones, they may well be able to access increasingly sophisticated civilian models that can serve their interests. The U.N. Security Council reported last year that several African member states have confiscated manuals with instructions for drone use in targeted attacks. The increasing availability of commercial, ready-made, or easily fabricated modifications also increases the risk of groups attempting to adapt drones to carry out limited attacks.

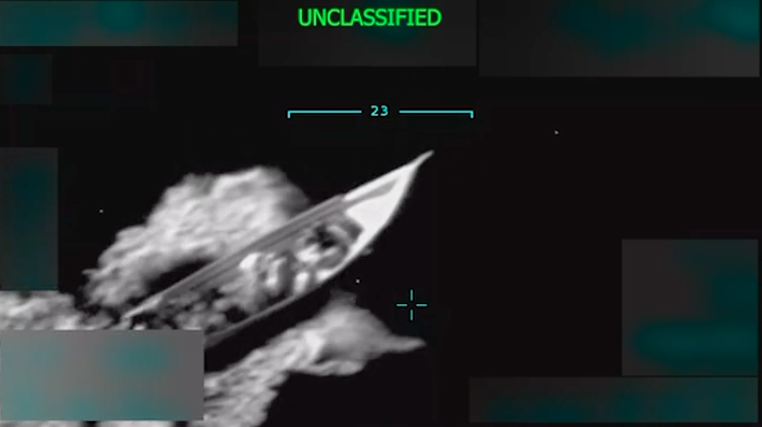

The second enabling factor is the trafficking of technology and weapons from other zones of conflict. Porous borders and domestic conflict in the region have made it difficult for authorities to police weapons smuggling. The U.S. Treasury reported in October 2022 that an illegal weapons trafficking network had been supplying weapons—including improvised explosive device (IED) components, ammunition, and small arms—from Yemen to Somalia, including to al-Shabaab and the local Islamic State affiliate. These weapons were allegedly Iranian made and meant for the Houthi rebels in Yemen. While this is not a new smuggling route and there has been no evidence of drones being transported via this network thus far, the likelihood of similar networks transferring drone technology from Yemen into Africa is possible given the prevalence of drone technology that is already present in Yemen and used by the Houthis. Since 2018, the Houthis have carried out numerous drone attacks targeting strategic facilities in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

The third and final factor is the confiscation of equipment from government forces. Islamic State-affiliated groups in Africa—such as ISWAP, ISCAP and IS-Mozambique—regularly ambush military establishments and seize military weapon caches. Drones and other specialized equipment may be obtained this way. This has occurred in at least several instances. IS-Mozambique reportedly seized a reconnaissance drone from the Mozambican Army in January 2023, and in September 2020 ISWAP reported on social media that it had captured a “Phantom” (likely a DJI Phantom commercial drone) during an attack on Nigerian forces. Al-Shabaab even captured a U.S. ScanEagle drone, posting pictures of it in September 2022, but they are unlikely to be able to repurpose it for their own use.

Implications for Terrorist Group Capacity

Terrorist groups in Africa face few obstacles to accessing commercial drone technology, but so far they have been slow to weaponize this capability, as groups have elsewhere. Two possible reasons stand out for why this is the case. First is a lack of technical capability. African terrorist groups might still lack the technical know-how for adapting drones for delivering munitions. In October 2014, an Islamic State defector told the International Crisis Group that ISWAP members had sent pictures of an unarmed drone to colleagues in Syria asking them what the object was. Islamic State militants in Syria replied with video instructions for assembling and using it. If technical knowledge is an impediment, it is unlikely to persist. Weaponizing off-the-shelf hobbyist drones is now entirely possible with commercially available equipment. With simple communications between Islamic State affiliates in Africa and the Middle East and the prevalence of online manuals and material, this obstacle may be easily overcome.

A second reason African terrorist groups may be reluctant to weaponize their drones could be caution. An active-offensive use of drones may prompt an increased counterterrorism response, and the groups may be avoiding a potential escalation with security forces. But strategies and operational objectives are always subject to change, and the fact that these groups have not weaponized their drones does not mean that they won’t in the future.

As the regional conflict grows and terrorist groups hold more territory, terrorist groups may well turn to weaponized drones. The threat will almost certainly not come from advanced, military-type drones; instead, groups are likely to use repurposed commercial, off-the-shelf drones, as has been seen on battlefields in Iraq, Syria, and more recently in the conflict in Ukraine. Counterterrorism forces in the region must remain vigilant, well equipped, and prepared, and they must focus on preventing terrorist groups from obtaining drone technology, as it is likely only a matter of time before weaponized drones hit the skies in Africa.