The Hawley Act Threatens AI Innovation

Senator Hawley’s new bill seeks to cut U.S. AI ties with China but risks stifling innovation and hurting U.S. technical dominance instead.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

“What protection teaches us, is to do to ourselves in time of peace what enemies seek to do to us in time of war.” —Henry George

On Jan. 29, Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) introduced the Decoupling America’s Artificial Intelligence Capabilities from China Act of 2025 (DAAICCA) as a sweeping attempt to sever U.S. artificial intelligence (AI) development from Chinese influence.

The bill, following hard on the heels of Chinese advances in AI and accusations of impropriety from U.S. technology companies, argues that stringent restrictions on the import, export, and collaboration of AI technologies between the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) are necessary for both national security and America’s economic independence. However, the bill’s rigid structure fails to take into account the globalized nature of software, hardware, and talent supply chains that benefit U.S. firms aiming to develop AI technologies. Ultimately, the DAAICCA will disrupt the open-source development of new tools and methods and create significant enforcement challenges.

Taken together, the limitations of the bill, as currently drafted, will stifle American AI progress.

Background and Context

The introduction of DAAICCA comes amid escalating concerns over China’s advancements in artificial intelligence. On Sept. 12, 2024, OpenAI released the o1 model, which marked a major leap in reasoning ability. Normally, AI models generate answers in a single step, much like “trusting your gut” on an answer based on what has been previously learned. The o1 model introduced “test-time computation,” meaning it doesn’t just make a single guess—it takes extra time to “think through” the problem, generating multiple possibilities, reasoning about them, and refining its answer before settling on the best one. This allows it to tackle more complex questions with greater confidence and accuracy.

Recently, the Chinese startup DeepSeek released R1, an open-source implementation of this “test-time computation” reasoning model. DeepSeek R1 is on a par with OpenAI’s o1 while operating on a limited budget, marking a significant breakthrough for the Chinese AI sector. DeepSeek R1 has served as a sobering wake-up call for the American AI industry, which has been investing heavily in computational resources to stay ahead of the competition. While DeepSeek has claimed that it achieved this feat with inferior hardware and only a fraction of the budget of OpenAI, the U.S. is reportedly investigating whether DeepSeek actually possesses more advanced, and therefore more expensive, hardware that allows it to compete more effectively.

The success of DeepSeek has not come without scrutiny. OpenAI has alleged that DeepSeek leveraged outputs from OpenAI’s models to achieve its performance, intensifying fears of intellectual property theft and unauthorized knowledge transfer. The rapid rise of DeepSeek has not only disrupted market dynamics but also led to significant fluctuations in technology stocks, underscoring the economic implications of AI competition.

Hawley has stated that his goal for the DAAICCA is to “[ensure] American economic superiority [by] cutting China off from American ingenuity and halting the subsidization of CCP innovation.” However, we argue that the mechanism by which the act will attempt to achieve these goals will ultimately harm American innovation instead.

Key Definitions

To fully understand the implications of DAAICCA, it is essential to clarify some key definitions outlined in the bill:

- Chinese entity of concern: The bill defines this as any entity, including corporations, universities, and research institutions, that is organized under the laws of the PRC, has its headquarters or principal place of business in China, or is affiliated with the Chinese Communist Party or the People’s Liberation Army.

- United States person: This includes U.S. citizens, permanent residents, corporations incorporated under U.S. law, research institutions, and universities. The bill also extends the definition to cover any entity controlled by a U.S. person.

- Artificial intelligence and generative artificial intelligence: The bill adopts definitions from existing U.S. legal frameworks, describing AI as any system capable of performing tasks such as decision-making, learning from experience, and generating human-like outputs.

The definitions provided for AI and generative AI in the bill are extremely broad. They would include software such as search engines, weather forecasting models, self-driving autopilots, and almost any program with predictive functionality. In fact, the definition inadvertently targets all software in existence by defining AI as any “artificial or automated system, software, or process that uses computation … to determine outcomes … collect data or observations, or otherwise interact with humans[.]”

Other definitions not included in the act but that are necessary to define are open- and closed-source software. Open-source software is software that is made freely available for public use. In the context of AI, open-source AI refers to codebases that allow anyone to freely train and create an AI model, such as a large language model (LLM). Closed-source software is proprietary to an organization and not available to the public for reproduction, verification, or validation.

DAAICCA Will Kill AI Development and Open-Source Software

Section 3(a) of DAAICCA prohibits the import of any AI technology or intellectual property (IP) developed or produced in China. This raises immediate concerns given the extensive integration of Chinese researchers and entities in global AI projects.

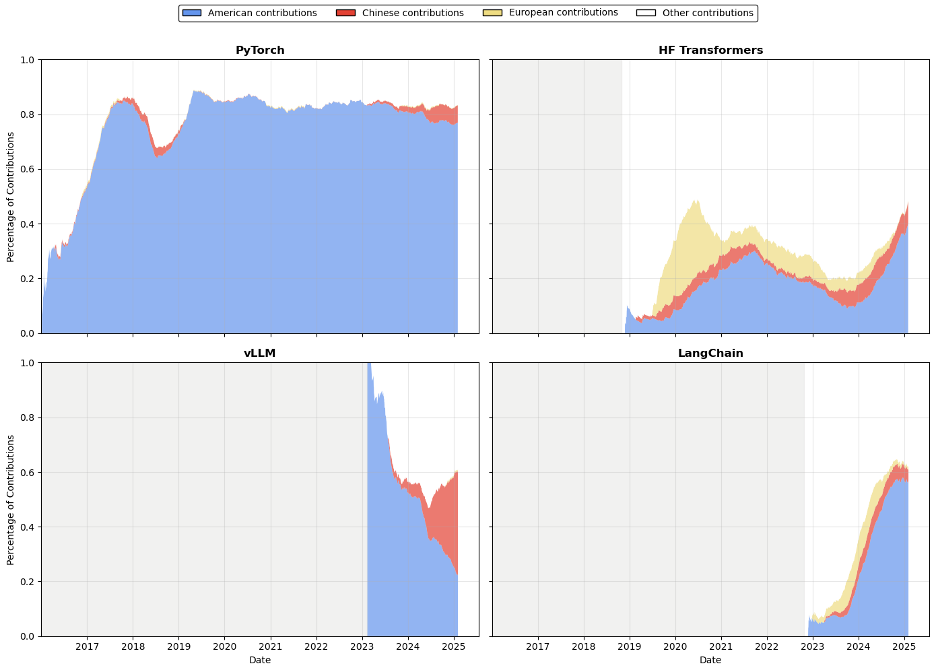

Major AI projects—such as PyTorch, the most popular deep learning library used to build neural networks; NumPy, a highly used linear algebra codebase; and even toolkits to perform efficient generation from LLMs such as vLLM—contain code contributions from Chinese researchers and engineers at Chinese entities of interest (Figure 1). American companies and researchers are prolific users of mmdetection and mmsegmentation, libraries for image understanding created and primarily maintained by OpenMMLab, a Chinese organization. Closed-source software is entirely reliant on open-source software—undoubtedly OpenAI’s ChatGPT uses PyTorch, NumPy, and other open-source libraries as part of their closed-source stack.

We can visualize this by plotting the contributions of major Chinese, American, and European companies and universities to AI-related codebases (see Figure 1). We analyze the total lines of code contributed to the codebase every day by a subset of American, Chinese, and European organizations. Evidently, major AI and AI-related codebases are built jointly by Chinese, American, and other authors from across the globe.

Figure 1. The amount of code contributions (line of code additions and removals) per day split by regions that possess major AI organizations.

If this legislation is passed in its current form, how will American organizations and individuals ensure they are not importing any Chinese AI contributions? The U.S. government and the private sector continue to struggle with understanding the provenance of any codebase despite mandating software bills of materials—exhaustive lists of every external software dependency used in a program and their country of origin—in 2021.

Similarly, Section 3(b) of the bill concerning the prohibition on the export of AI technology or IP to China poses a major challenge to open-source AI development given its apparent breadth. The bill effectively classifies publicly available AI models and research as potential exports, making it nearly impossible to share advancements without running afoul of export control laws. If a researcher from a U.S. organization engages in the norms of the computer science community and publicly shares their AI codebase, and an entity of concern from the PRC downloads the code, this would be considered an export. This disproportionately affects smaller entities—startups, independent researchers, and academic institutions—that lack the resources to implement the kind of gating mechanisms that large corporations might be able to afford. This further affects the U.S. government itself, a prolific user of open-source software that is currently using a large amount of open-source AI for its activities. As OpenAI considers shifting to an open-source strategy itself, this legislation would stymie those efforts before they start.

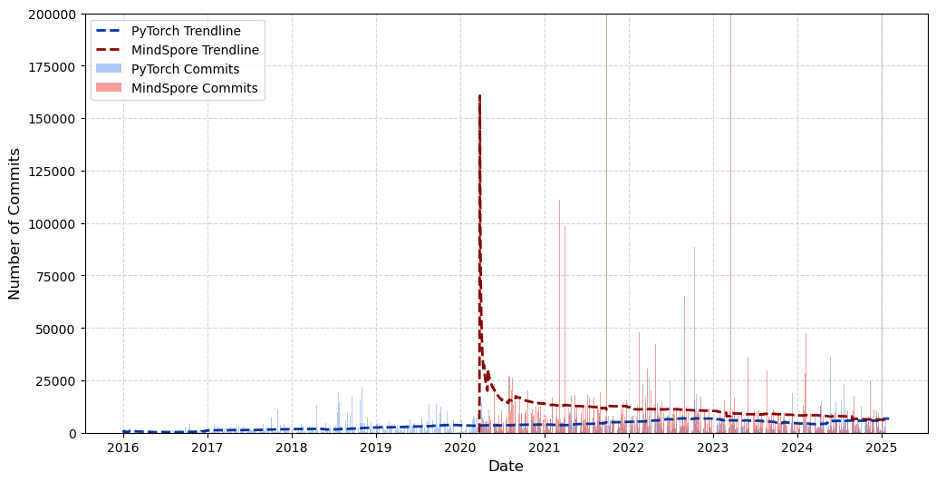

The increasingly fragmented nature of the AI ecosystem along national lines is hurting the U.S. by taking away useful contributions from accessible codebases. China is investing heavily in its own deep learning framework, MindSpore, reducing dependency on the popular, American-originated PyTorch framework. Both frameworks support machine learning code on various accelerators, but MindSpore has paid special attention to optimization for the Chinese Huawei Ascend GPU. These optimizations have paid off; DeepSeek tested the Ascend 910C GPU as part of training the R1 model, and its performance is already 60% that of the export-controlled NVIDIA H100 GPU. These optimizations, however, are not exclusive to the Ascend GPU—if the engineering effort behind MindSpore had been directed toward PyTorch, it could have improved performance across all hardware types. Despite PyTorch benefiting from global contributions, MindSpore, developed almost solely by Chinese researchers, appears to be progressing at a similar rate (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Amount of daily code contributions to popular American- and Chinese-originated deep learning frameworks, PyTorch and MindSpore.

Historically, fundamental research, defined as basic scientific research that is meant to be shared broadly with the community, has been protected and exempted from export and arms regulations. Specifically, the National Security Decision Directive 189 (NSDD-189) provided safe harbor exemptions in a sweeping reform to ensure American academic superiority and free exchange of ideas. This has allowed American academia to thrive and become an industrial and scientific superpower. It is therefore concerning that Section 3 of DAAICCA would overturn decades of “safe harbor” precedent in a misguided attempt to protect that same innovation.

Collaboration and Investment Restrictions

Beyond trade restrictions, DAAICCA also prohibits U.S. persons from engaging in AI research and development with Chinese entities of concern. This includes direct collaboration, as well as research partnerships with universities and corporations that have ties to the PRC. Organizations in China and America collaborate frequently. In fact, this trend has been increasing over the past decade, with the share of American-Chinese co-authored papers accounting for over 10 percent of all AI publications in top venues. More pressingly, 19 percent of all American AI publications have a Chinese co-author, while only 10 percent of Chinese AI publications have an American co-author, suggesting that American authors more frequently seek out Chinese collaborations than the other way around. Under this legislation, such contributions would be retroactively considered problematic, significantly limiting the ability of U.S. researchers to engage with leading global talent.

Additionally, Section 5 of DAAICCA would ban U.S. persons from holding an interest in Chinese entities involved in AI research and development. This move codifies the Biden administration’s rule blocking American investment in Chinese technologies that pose a risk to national security, including artificial intelligence. However, many major U.S. technology companies operate major AI research centers in China, such as Microsoft Research Asia and Apple. Many influential AI breakthroughs have emerged from such collaborations, such as the Swin Transformer model from Microsoft Research Asia, which won the Best Paper Award at a top-tier AI conference. Ultimately, research produced by U.S. corporate research labs in China remains the IP of U.S. companies—blanket banning all investments in China for AI would kill this source of innovation entirely.

Unintended Consequences

Despite its broad prohibitions, the bill leaves critical questions unanswered. One major ambiguity is whether Chinese students studying AI in the United States can work in U.S. laboratories given the potential for them to return to China following the completion of their respective programs. Would universities hosting such students be held liable for “aiding and abetting” under the law? In addition to concerns at the completion of their programs, many Ph.D. students maintain ties with their alma maters to finish their ongoing research threads and reach publication. Being forced to sever these ties could lead Chinese students to avoid American universities, stifling an important talent pipeline given that many seek to stay in the United States upon graduation.

Separately, the bill references an “implication in human rights abuses” as a criterion for restrictions, but it provides no clear definition of what constitutes such an implication. The bill should update its language, similar to how it has in other sections, to reference 22 U.S.C. § 2304, which defines “gross violations of internationally recognized human rights” as introduced by the Leahy Laws.

Policing the Bill

Academics and policymakers tend to focus on the draft language of the bill in terms of what it allows and prohibits. How this bill would be implemented and enforced is ultimately more important than what it statutorily prohibits.

In the bill’s current form, given its breadth and ambition, there are real concerns as to the ability of U.S. government agencies to monitor compliance with its strictures. At present, the small teams from the Department of Justice and Department of Commerce in technology hubs like Silicon Valley, Boston, Atlanta, Austin, and even Washington, D.C., that would monitor, enforce, and report compliance are threadbare.

At the same time—and as is the case in other areas of government—there is a clear dearth of AI talent inside the government as it seeks to address the governance and regulatory challenges associated with AI technologies. Implementing DAAICCA requires that these limits in human capital be addressed—whether by existing institutions like the Department of Homeland Security’s AI Corps, the General Service Administration’s 18F, or entirely new programs.

Expanding the ability of the U.S. government to police its existing export control mechanisms and contribute to an important nationwide discussion concerning research security concerns is no doubt necessary. However, current efforts to shrink government appear to leave efforts like this one a paper tiger.

A Path Forward

While DAAICCA is driven by legitimate concerns regarding China’s strategic use of AI technologies in government and military contexts, its rigid restrictions could undercut American competitiveness in the long run.

In its current form, DAAICCA appears likely to do more harm than good. If enacted, it will isolate U.S. AI researchers, undermining collaboration and creating a bureaucratic maze of compliance hurdles that would hinder rather than further U.S. leadership. Due to its broad impacts on American interests, the bill is unlikely to pass Congress without heavy modifications.

In today’s AI ecosystem, fundamental research advancements are put into production by highly funded industry AI labs in a matter of days. This tight coupling of the basic and applied research pipelines is unprecedented and leaves little room for legislative efforts. Attempting to control applied AI advancements kills fundamental AI advancements.