The Patel Dossier

Everything you want to know about Kash Patel—and so very much more.

.jpg?sfvrsn=1111cf9d_4)

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Kash Patel today goes before the Senate Judiciary Committee, which is considering his nomination to be director of the FBI. To say that Patel is an unusual nominee would understate the matter considerably.

Unlike all previous directors of the bureau, Patel’s background is overtly partisan and political. He is the only nominee to the position to sell branded wine, to write children’s books, or to have a long history of conspiracy theorizing. He is also unique in that nearly every aspect of his professional career carries with it some measure of controversy—everything from the suggestion that he has inflated his role in events to the belief, publicly alleged by senior officials, that he endangered American troops overseas. He has suggested that the law enforcement apparatus has been used politically against President Trump—and that Trump should use it against his own foes. And he is a central figure in crafting the mythology, so key to discrediting the Russia investigation, of the so-called “Steele Dossier.”

To help people make sense of Patel’s career, we have compiled what one might call “The Patel Dossier.” It is an attempt to assemble, describe, and document the major controversies that have amassed around Patel. We have used the public record only. In most cases, we have begun with Patel’s own book, and then looked for other accounts of the same events. With respect to many issues we describe, the record is frankly incomplete. There’s a great deal of room for senators at Patel’s hearing to get him on the record responding to allegations and clarifying his own statements and claims.

The Public Defender

Though Patel likes to describe himself as a “guy from Queens,” he grew up about an hour away on Long Island, in the village of Garden City. As a high school student, Patel caddied for “wealthy” and “important” New Yorkers at the Garden City Country Club. It was there that Patel first developed an interest in pursuing a career in law. In his book, Government Gangsters: The Deep State, the Truth, and the Battle for Our Democracy, Patel recounts listening to a group of defense lawyers discuss their work as they “hit the links” at the Country Club. “I didn’t understand exactly what they did, but being a lawyer sounded interesting,” Patel writes. Off he went to the University of Richmond and then Pace University’s law school, where he dreamed of becoming “a first-generation immigrant lawyer at a white shoe firm making a ton of money.”

Patel’s Big Law dreams never materialized. “Nobody would hire me,” he explains in his book. On the advice of a friend, Patel applied for a job with the public defender’s office in Miami-Dade County, Florida, which he describes as the “number one defense office in the country.” To Patel’s surprise, he got the job.

By his own admission, working as a public defender was a “strange fit” for Patel. Throughout his college years, Patel’s political beliefs had moved “more and more” to the right. His ideological perspectives didn’t quite square with the views of many of his colleagues, who, according to Patel, were “far left of the left-wing.” Still, Patel insists that he “couldn’t be happier” that he became a public defender. “Yes, some of my colleagues were crazy,” Patel writes. “But me, I always cared about justice and wanted those who did good to be rewarded and wrongdoers to be punished…The most effective way to reach the right results in each and every case is to have the right process—to have due process—and public defenders are essential to achieve due process.”

Patel worked as a public defender—first in state court in Miami-Dade and, later, in federal court in the Southern District of Florida—for nearly nine years. Reading Government Gangsters, it’s clear that Patel’s work in indigent defense was a formative experience, imparting him with an early distrust of federal law enforcement. “Honestly, I can’t tell you how many times I caught the feds abusing due process or lying on the witness stand,” he writes.

The Federal Prosecutor

Despite Patel’s professed misgivings about “feds,” he eventually joined their ranks. By 2014, he landed a job as a federal prosecutor in the National Security Division at Main Justice—the Justice Department’s headquarters—in Washington, D.C. But, as Patel tells it, what should have been a “dream job” for an ambitious, young, thirtysomething lawyer turned out to be an education in the “failings” of the Justice Department from the inside. “I soon realized that my bosses at HQ didn’t have my back,” Patel writes. “Ultimately, they were more concerned with politics and optics than with defending those who wanted to serve the institution."

According to Patel, his first lesson in this alleged “optics, not justice” ethos began with the Sept. 11, 2012 attack on the American Embassy in Benghazi, Libya. Shortly after he joined the Justice Department, Patel was assigned to the team of prosecutors who were tasked with conducting a criminal investigation into the terror attack that killed four Americans. In his book, Patel says that he was “leading the prosecution’s efforts at Main Justice” by the time the Justice Department began bringing charges against individuals involved in the attack. He then claims that he watched Justice Department officials in the Obama administration “go soft” on terrorists by deciding to pursue charges against a single suspect. “Despite the fact that we had reams of evidence against dozens of terrorists in the Benghazi attack, Eric Holder’s Justice Department decided to only prosecute one of the attackers,” Patel writes. In his telling, deep skepticism about the prosecutorial decision-making of the Justice Department’s leadership prompted him to decline an offer to join the trial team for the prosecution of a Libyan militia leader accused of planning the attacks.

According to reporting published in multiple media outlets, including The Atlantic, The New York Times, and MotherJones, Patel exaggerated his role in the Benghazi investigation and misrepresented the Justice Department’s efforts to prosecute individuals involved in the attacks. While Patel did work on the Benghazi investigation, the prosecution was led by representatives from the U.S. Attorney’s Office—not Main Justice, where Patel worked. According to the Atlantic, Patel was never asked to join the trial team. And the New York Times reports that it’s simply not true that the Justice Department only pursued a single prosecution related to the attack. As early as 2013, according to the Times, the Justice Department had already filed sealed complaints against about a dozen militants.

The Justice Department’s handling of the Benghazi investigation wasn’t the only source of Patel’s growing disillusionment with the federal government. In his book, Patel recounts the locus of his grievance against his supervisors at the Justice Department: a 2016 incident in which a judge in Texas reprimanded Patel about his courtroom attire.

In January 2016, Patel explains, he had traveled to Tajikistan to interview witnesses for a terrorism case related to the Islamic State. While he was still there, a judge in Texas called a hearing for another case to which Patel had been assigned. With less than a day’s notice before the hearing, Patel flew back to the United States, landing in Texas only an hour before the scheduled start time, according to a transcript of the proceeding. Having not brought a suit and tie with him to Tajikistan, Patel says he showed up in court wearing “pants, a button down, and a blazer.”

What ensued was a bizarre dressing-down of Patel by the judge, Lynn Nettleton Hughes. He berated Patel for showing up without a tie—and then scolded him for showing up at all. “Dress like a lawyer,” the judge said. “Act like a lawyer,” he commanded. He proceeded to accuse Patel of being just “one more non-essential employee from Washington,” who had “no independent utility.” The judge summarily dismissed Patel from his chambers. Later, after the Justice Department attempted to obtain a copy of the transcript from the hearing, Judge Hughes issued an “Order on Ineptitude” that blasted the “pretentious lawyers” from Main Justice.

To be sure, a transcript of the confrontation shows that Patel acted professionally throughout the exchange, despite the judge’s curmudgeonly missives. And, according to Patel, senior leadership at the Justice Department privately told him that they were “furious” over the episode, praising him for keeping his cool.

For Patel, the problem was that the Justice Department refused to come to his defense publicly. In the wake of the incident with Judge Hughes, several media outlets reported on the confrontation, including the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal. The Justice Department, for its part, declined to comment on the stories. The initial stories on the incident, which recount details of the transcript at length, make reasonably clear that the judge, not Patel, was in the wrong.

Still, Patel felt aggrieved by his portrayal in the media reports. The media, he writes in Government Gangsters, “had the judge’s side of the story and that was it, so they ran with it and dragged my name through the mud.” All the while, Patel writes that his superiors at the Justice Department “did nothing.” In his view, the inaction owed everything to a single calculation: “They didn’t want to stick their necks out to defend one of their own because they didn’t want to risk bad press or getting in a spat that might tarnish their reputations.”

Within a few months of the incident, Patel left the Justice Department.

The Nunes Memo

Kash Patel “NEVER” wanted to work on the Hill.

For one thing, being a congressional investigator didn’t sound all that exciting. He thought it was the kind of work that would result in “some boring report” that “very few people would ever care about or read.” Besides, Patel had his sights set on his “dream job”: A position at the National Security Council (NSC) in the Trump White House.

But Devin Nunes is nothing if not persuasive.

At least, that’s how Patel tells it in Chapter 4 of Government Gangsters, in which he recounts his reluctant career shift from federal prosecutor to Congressional staffer. In the book, Patel insists that he wasn’t interested in a job in politics when he met Nunes (R-CA), a Republican Congressman and then-chairman of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI). At the time, Nunes’s committee was investigating Russian interference in the 2016 election and the origins of the FBI’s investigation into the same. While Patel initially sat down with Nunes as a favor for a friend, the two got along “right off the bat.” The congressman eventually persuaded Patel to join his team as an investigator on the Russia matter.

Patel spent several months examining the FBI’s investigation into ties between the 2016 Trump campaign and Russia. He zeroed in on the FBI’s applications to surveil Carter Page, a Trump campaign aide with ties to Russia, under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). The applications relied in part on claims set out in the so-called “Steele Dossier,” a compilation of political opposition research about Trump. The central allegations in the dossier, which was authored by a former British intelligence agent named Christopher Steele, have since been discredited.

In 2018, Nunes released a much-hyped, four-page memo on alleged surveillance abuses by the FBI and the Justice Department during the Russia investigation. The memo, which Patel says he drafted, claimed that law enforcement heavily relied on the “Steele dossier” to obtain a FISA warrant on former Trump campaign adviser Page in October 2016. It further alleged that agents failed to adequately explain to the FISA court that the dossier’s author, Steele, had voiced opposition to Trump and had received funding from the Democratic National Committee and the Hillary Clinton campaign.

Patel’s instinct about the Steele material was correct, at least in part. A lot of it turned out to be garbage. He was also correct, as the Justice Department’s inspector general later found, that the FISA applications based on it were significantly flawed. There were numerous errors in them.

At the same time, Patel, Nunes, and Trump have always made too much of the role that the Carter Page FISA warrants, and thus the Steele materials, played in the larger Russia investigation. This was not, in fact, how the Russia investigation started. It also never panned out, which is unsurprising given that some of the underlying information was incorrect. So none of the many prosecutions brought but the Robert Mueller investigation rely on the Steele materials. And none of the very damaging factual claims in the Mueller Report owe anything to Steele. Patel talks about the Steele material and the Carter Page FISAs as though they were the root system of a rotten tree—the fruit of which is all poisoned. In fact, it was a small branch of a very large tree, one that withered and died and never produced fruit at all.

The White House

By the fall of 2018, with the Nunes Memo published and with the Democrats poised to retake the House, it was time for Patel to move on. Nunes, who had promised two years earlier that he would help Patel secure a position at the National Security Council, spoke to Trump on his staffer’s behalf. According to Government Gangsters, the congressman told Trump that Patel had “saved his presidency by revealing the unprecedented political hit job designed to take him down.”

It worked. “When President Trump learned who I was and what I did, he told his chief of staff to hire me immediately onto the NSC,” Patel recalls.

But Patel had a problem: John Bolton, the then-national security advisor whom Patel has described as an “arrogant control freak.” According to Patel, Bolton “threw up roadblock after bureaucratic roadblock to prevent me from being hired.” Eventually, Trump told Bolton to “cut the crap.” Reluctantly, Bolton hired Patel, initially placing him in the International Organizations Directorate, which had a vacancy at the time. Several months later, Bolton moved Patel over to the Counterterrorism Directorate. There, Patel claims he rose to the rank of senior director of counterterrorism, which he describes as the top dedicated counterterrorism official in the Trump White House.

Bolton has similarly described the machinations leading up to Patel’s hiring at the NSC. In a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed, Bolton describes his reluctance to hire Patel, even at Trump’s urging, citing his “utter lack of policy credential,” his “puffery,” and his proclivity for “resume inflation.”

But Bolton vehemently disputes Patel’s account of what he actually did at NSC once hired. According to Bolton, Patel never ascended to the role of senior director, as he contends in his book and elsewhere. At both of his NSC roles—first at the international organizations directorate and then at the counterterrorism directorate—Patel reported to senior directors and “had defined responsibilities.” Assessing Patel’s work, Bolton surmises that Patel was “less interested in his assigned duties than in worming his way into Mr. Trump’s presence, which evidenced he was duplicitous, manipulative, and conspiratorial.”

As an example of Patel’s duplicity, Bolton points to the Congressional testimony of the former NSC Senior Director for Europe, Fiona Hill, during Trump’s impeachment hearings. Hill testified that Patel, who at that time was assigned to work for the International Organizations Directorate, “participated in a May, 2019, Oval Office meeting on Ukraine, and that he had engaged in various other Ukraine-related activities.” According to Bolton, any work Patel did on Ukraine was “unrestrained freelancing” outside of the normal NSC channels.

Patel, for his part, has denied Hill’s account. “At no time have I ever communicated with the president on any matters involving Ukraine,” he told Axios in 2019.

Bolton would not be the last White House official to raise concerns about Patel’s qualifications for a position in the administration, As Patel increasingly curried favor with Trump, the president and his allies began to advance the idea of installing him in a variety of key roles. On several occasions, according to multiple sources, White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows floated the idea of appointing Patel as deputy director of the FBI. But when he ran the idea by Bill Barr, the then attorney general, Barr balked. “Over my dead body,” Barr replied, according to his memoir.

In Peril, Carl Woodward and Robert Costa report that Barr then proceeded to cast aspersions on Patel’s qualifications for the job. “Everyone in that building is an agent. They’ve all been through the academy…The only person who is not an agent is the director,” he reportedly told Meadows. “Do you think that son of a bitch is going to go over there and command respect from these guys? They’ll eat him alive.”

Eventually, Barr explains in his book, the subject died.

Nor is Hill’s testimony about the Ukraine matter the only time that Patel has been accused of flouting institutional protocol. CBS News reports that, in the leadup to Patel’s confirmation hearing, Senate Democrats have obtained information from an FBI whistleblower about Patel’s conduct during an operation to retrieve two Americans from Iranian-backed militants in Yemen in October 2020. According to CBS, the whistleblower alleges that Patel violated firmly entrenched protocols to keep such operations under wraps until the captives are safely in U.S. hands and their families have been notified. The report cites a Wall Street Journal article, published on Oct. 14, 2020, at 10:55 a.m., in which Patel confirmed that two Americans and the body of a third were exchanged for two hundred Houthi fighters. The article was published “several hours” before the hostages were in the confirmed custody of the United States, according to CBS. While the Americans were returned safely, Patel’s comments went against long standing FBI protocol to maintain secrecy around such operations until the hostages were in U.S. custody. Senate Democrats have reportedly requested additional information about the incident from various federal agencies.

About two weeks after the Yemen operation, there was another dust-up over a rescue mission, this time in West Africa. That week, on Oct. 29, 2020, American officials learned that a 27-year-old American named Phillip Walton had been abducted from his home in Niger, near the country’s border with neighboring Nigeria. As Mark Esper, Trump’s then-secretary of defense, recounts in his memoir, American forces quickly assembled operations to rescue Walton.

The next day, on Oct. 30, 2020, according to multiple news reports and Esper’s memoir, a team of Navy SEALs stood by on a plane in West Africa, awaiting the green light from the Pentagon. As the State Department worked to secure permission to enter the airspace of a key country, a Department of Defense official received a call from Patel, who then still worked in counterterrorism at NSC. As described in Esper’s book, Patel told the Pentagon that Secretary of State Mike Pompeo had “got the airspace cleared.” The mission could proceed.

A few hours later, as the military aircraft carrying the SEALs neared the Nigerian border, Esper learned some disturbing news: The Secretary of State had not, in fact, secured permission to enter the airspace. What Patel told the Pentagon earlier that day was wrong; the State Department was still working on securing airspace clearance.

The SEALs were forced to temporarily divert the operation, circling the aircraft in approved airspace as they awaited further instructions from the Pentagon. Esper, for his part, called Pompeo to find out what happened. According to Esper, Pompeo said he didn’t know where Patel got his information. Pompeo never spoke to him. “My team suspected Patel made the story up,” Esper recalls in his memoir, “but they didn’t have all the facts.”

Whether made up or not, the miscommunication put the mission—and American lives—at risk. With the clock ticking, Esper and other Pentagon officials weighed the options. If they waited much longer for permission to cross the border, the aircraft would have to return to its base and the operation would have to be rescheduled for another evening, during which time Walton could be moved or killed by his captors. On the other hand, as Esper puts it in his memoir, proceeding with the mission without airspace approval “would technically be an invasion of a foreign country.”

Esper and Pompeo called the president and his Chief of Staff, Mark Meadows, to brief them on the options. “We recommend the mission go forward. But the president has to make that call,” Esper told Meadows. Then, as Meadows began to ask questions, they received breaking news from the Situation Room. It was Deputy Secretary of State Steve Biegun on the line: “The overflight rights we requested were approved.”

The mission was a go. Soon after, Walton was safely returned home.

Still, Pentagon officials were livid with Patel. According to Esper, the incident prompted one senior official, Anthony Tata, to confront Patel, which quickly devolved into “verbal fisticuffs” and “yelling at each other.”

Patel, for his part, has claimed that Esper “falsely attacked” him. As he recounts the story in his book, the hostage mission was a “greenlight” until Esper “swooped in” and sent word that the operation was a no-go. “In the Situation Room, I was told what Esper did, so I sent the message back that the commander in chief personally greenlit the mission, so unless there was a threat to our forces, the boys were jumping,” Patel writes. The next day, according to Government Gangsters, Esper sent word to the White House that he wanted Patel fired. In Patel’s eyes, it was a “personal vendetta” for Esper. “Amid all this, the President agreed that Esper had to go,” Patel further claims in his book.

Several weeks later, shortly after Election Day, Trump fired Esper. Patel says he received a job offer later that same day. The president wanted him to serve as the chief of staff for Chris Miller, who had just been named acting secretary of defense in the wake of Esper’s departure. Patel was “honored” to take the job.

While Patel’s conduct during the Walton rescue mission raised private concerns among his colleagues, another incident that occurred that year would result in something more concrete: a criminal referral to the Justice Department. The referral, as reported earlier this week by CNN, came in the waning months of the first Trump administration, when the CIA requested that the Justice Department investigate Patel’s handling of classified information. While information about the circumstances of the referral are sparse, CNN reports that the CIA “claimed in its referral Patel circulated a memo in 2020 to people inside the US government about Russian efforts to interfere in the 2016 presidential election.” The intelligence agency had not authorized that information to be declassified, and some of the people who received the memo didn’t have the proper level of clearance to see its contents, according to CNN.

In addition to the criminal referral, a “flag” was placed in Patel’s security clearance file, as is common practice when individuals who maintain security clearance are referred for criminal investigation. The flag reportedly remains on Patel’s file inside the FBI’s security clearance database.

Ahead of Patel’s confirmation hearing, Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), the Ranking Member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, sent a letter to the Justice Department and several intelligence agencies requesting information about allegations of misconduct against Patel, including referrals to the Justice Department.

Patel disputes the facts alleged against him in each of these cases. It is remarkable, however, that officials as diverse as Bolton, Hill, Barr, and Esper all publicly have suggested that he acted beyond his remit or have questioned his truthfulness about important matters of state. At a minimum, one would think the Senate Judiciary Committee would want to clarify Patel’s role in the incidents in question before installing him at the helm of the FBI.

January 6th

Kash Patel had plenty of reasons to be preoccupied in the lead up to Jan. 6.

For one thing, he had election conspiracy theories to investigate.

In November, after Joe Biden defeated Patel’s boss in the presidential election, Trump and his allies had set off on a frantic quest to overturn the results of the election by parroting false or misleading claims about supposed voter fraud or other irregularities. As Trump and his lawyers searched for evidence of fraud, Patel, in his new role at the Defense Department, took an interest in one of the more outlandish conspiracy theories: The idea that an Italian defense contractor uploaded software to a satellite that switched votes from Trump to Biden. According to Richard Donoghue, then the acting deputy attorney general, Patel called him sometime in late December or early January to inquire about the theory. Donoghue was dismissive, telling Patel that there wasn’t anything to it. Still, around that time, Patel’s direct boss, Acting Secretary of Defense Chris Miller, went so far as to place a call to the Italian defense attache, inquiring about the conspiracy theory.

Judiciary Committee Ranking Member Richard Durbin has suggested that Patel was also at least peripherally involved in the attempt by then-Justice Department official Jeffrey Clark to deploy Justice Departments resources to overturn the 2020 election. Durbin, who conducted an investigation of the matter in 2021, alleges in a letter: “On January 2, 2021, then-Director of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) John Ratcliffe referred Mr. Clark to Mr. Patel. Then-Director Ratcliffe informed Mr. Clark that Mr. Patel purportedly could help identify a “trustworthy” individual at the FBI who would potentially be willing to aid Mr. Clark’s efforts.”

The claim is sourced to contemporaneous notes by Jeffrey Clark reflecting his Jan. 2, 2021 meeting with Ratcliffe.

Election conspiracy theories aside, Patel had plenty of other reasons to be preoccupied around that time. There was the Afghanistan withdrawal, for one thing. But, most of all, Patel says in his book that he was busy preparing for the presidential transition. Others might substitute a different verb, as Sen. Durbin recently did in a letter sent to federal agencies ahead of Patel’s confirmation hearing: Patel was busy “impeding”the presidential transition.

Two weeks after he arrived at the Department of Defense, Patel had been tasked with leading the Pentagon’s transition efforts.

In Patel’s version of events, which he recounts in Government Gangsters, the task was a “heavy lift.” It took a significant amount of effort to ensure that the incoming Biden staffers were “brought up to speed” so they could “govern effectively and defend the nation,” Patel emphasizes.

Yet, by some accounts, Patel’s own conduct during the transition seemed geared toward interfering with, rather than aiding in, the transition process. According to a Dec. 2020 NBC News report, Patel told officials at the Department of Defense that they are “not going to cooperate” with the Biden transition team. The report describes alleged “restrictions” Patel placed on the transition process, including by prohibiting some career officials and subject matter experts from providing key information on national defense issues to the transition team. In other instances, according to NBC, Patel “put a political spin” on information before sharing it with Biden transition officials.

The Pentagon, in a statement provided to NBC in response to the article, insisted that the Department of Defense had and would continue to work closely with Biden transition officials.

Privately, Patel was enraged by media coverage about the transition process, which he considered to be “damaging” and “false.” In the wake of one such unfavorable press report, Patel went so far as to insinuate that he would completely cut off access to the Biden transition team. "Tell Kath that if her or any ART team continues these total fake narratives, I will shut it all down,” Patel wrote in an email to his staff, using an acronym for the president-elect’s “agency review team,” which assists with the transition process. Asked about this email during his deposition before the Jan. 6 Committee, Patel acknowledged that “Kath” was a reference to Kath Hicks, a transition representative for the Biden team.

Speaking before the Jan. 6 committee, Patel downplayed the email. It was, he said, merely intended as a “hyperbolic statement to make sure my team understood the severity in which I wanted this matter adjudicated and the record corrected.”

Still, Patel has admitted—in both his Jan. 6 Committee deposition and in an op-ed published by Fox News—that the Defense Department did in fact “pause” the transition process in late December, not long after NBC published its report. In Patel’s account, the “pause” lasted for only “one day” so that Defense Department leadership “could focus on other pressing national security matters.” During his deposition before the Jan. 6 Committee, however, investigators pushed back on this claim: “The Biden-Harris folks’ recollection is it was a 3-week stoppage of any transition, occurring from mid-December and not reengaging until January,” an unidentified congressional staffer said, according to a transcript. “I just don’t think that’s something we would’ve done,” Patel replied.

Despite the criticism levelled at Patel over the transition, Patel gives himself a 5-star review in Government Gangsters: “All said and done, it was a masterclass in how presidential transitions go—even in the face of the egregious lies in the press.”

In this section of the book, which is subtitled “Peaceful Transition,” Patel doesn’t mention the thousands of rioters who stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6th, 2021, disrupting the Joint Session of Congress. Elsewhere in the memoir, however, he provides an account of Jan. 6th that is riddled with half-truths and outright falsehoods.

Some aspects of Patel’s account of Jan. 6th are relatively uncontroversial. On that day, Patel recalls, he was in his new office at the Pentagon, where he had been “almost every day” since being named chief of staff at the Department of Defense. “There was a very large crowd gathering at the Capitol, and it seemed all the regular tactics of crowd control were either not implemented or ineffective,” he recalls. Patel soon began to monitor what was going on at the Capitol more closely. “But at that point, like most every American, there was little we could do as we started seeing barriers overrun and people streaming through the doors,” according to Patel.

Then Patel begins to plant the seeds of conspiracy. Alluding to a popular right-wing theory that the attack on the Capitol was instigated by the FBI or FBI informants, Patel claims that there were all sorts of “strange agitators” that “stirred up the crowd” without facing consequences. As a part of this conspiracy theory, some on the MAGA right have focused on a rioter by the name of Ray Epps, baselessly claiming that he was an undercover FBI agent who helped incite the attack. In Government Gangsters, Patel indulges this theory, claiming that a top FBI official, Jill Sanborn, “dodged” questions about whether there were any FBI agents in the crowd on Jan. 6 and whether Epps was a “fed.”

“If the answer was ‘no,’ she would have said so,” Patel concludes. “All the signs of a cover-up are on display, as is the two-tiered justice system we have become so familiar with.”

Patel has repeated similar claims about the FBI’s role in Jan. 6 on podcasts and other media appearances, as Tom Josecyln and Norm Eisen have catalogued for The Bulwark. During a March 2023 interview with right-wing YouTuber Tim Pool, for example, Patel discussed the need to get to the bottom of the FBI’s involvement in order to “defeat the insurrection narrative.”

“We know they [FBI] were involved [laughing] . . . Ray Epps . . .,” Pool said at one point during the interview. Patel responded: “I totally agree.”

Claims that the FBI instigated the attack on the Capitol, as well as the related claim that Epps was working on behalf of the FBI to incite the riot, lack any sort of evidentiary basis. In a recently released report, the Justice Department’s inspector general, Michael Horowitz, found that the FBI “did not have any undercover employees” in the crowd that day. Though the report found that there were 26 individuals in the crowd that day with a history of passing on information to the FBI, it also concluded that the bureau did not order or authorize any of those individuals to instigate a riot or storm the Capitol.

What’s more, Epps has testified under oath that he has never worked for the federal government beyond his service in the military. Last year, when Epps was sentenced to probation for his relatively minor role in the riot, the presiding judge acknowledged the hardships he had endured as a result of the conspiracy theory. Epps, Judge James E. Boasberg said, “had to live like a fugitive because of lies others spread.”

Patel has pushed other false or misleading claims about Jan. 6. He has claimed, for example, that Trump authorized the deployment of “10,000-20,000” National Guard forces several days before the Joint Session of Congress. Patel testified to this fact on Trump’s behalf during a trial in Colorado state court on the question of whether Trump should be disqualified from the ballot under s. 3 of the 14th Amendment. The presiding judge, Sarah B. Wallace, found that Patel was not a credible witness. “His testimony regarding Trump authorizing 10,000-20,000 National Guardsmen is not only illogical (because Trump only had authority over about 2,000 National Guardsmen) but completely devoid of any evidence in the record,” she wrote.

The MAGA influencer

By the time Patel departed the White House, he’d racked up an impressive list of accomplishments: White House National Security Council. Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Chief of Staff to the Secretary of Defense.

With a resume like that, one might expect Patel to leave the White House and land a generous salary at a prestigious firm, finally accomplishing his high school dream of becoming “a first-generation immigrant lawyer at a white shoe firm making a ton of money.”

Instead, the former federal prosecutor and senior White House official opted to become a MAGA influencer.

In the years between the last Trump administration and this one, Patel launched an exhausting volume of content, merchandise, and other ventures. There was, for example, his 2021 effort to launch a payment processing site, “Paytriots,” which Patel reportedly pitched as a conservative answer to GoFundMe. Then there was a talk show, Kash’s Corner, which Patel hosted in partnership with The Epoch Times, a right-wing media publication. There’s a non-profit organization, The Kash Foundation, which is described as “dedicated to providing financial assistance to active duty service members and veterans, legal defense funds, and education programs.” And there is, of course, a merchandise company, Based Apparel, which sells shirts that read “Make America Based Again” and “Government Gangsters Playing Cards.” For $40, one can purchase the “Classic Fight with K$H” flag, the net proceeds of which are described as going to “The Kash Foundation fund which supports whistleblowers, education, defamation cases, etc.”

Patel’s post-White House influencing efforts often sought to reframe the narrative around the 2020 election and January 6th by pushing debunked or misleading claims. In one of his three children’s books, for example, Patel peddled the conspiracy theory that the 2020 election was stolen. The book, titled “The Plot Against the King 2000 Mules,” draws on Dinesh Disouza’s discredited film, 2000 Mules.

In 2023, Patel produced and promoted “Justice for All,” a musical recording that features several members of the “J6 Prison Choir” singing the Star-Spangled Banner from the Washington, D.C. jail. According to Patel, the J6 Prisoner Choir “consists of individuals who have been incarcerated as a result of their involvement in the January 6, 2021 protest for election integrity.” In promoting the song, Patel described the choir members as “political prisoners,” and he promised that the “net profits” would be used “to financially assist as many Jan. 6 families as we can, and all families of nonviolent offenders will be considered.”

The identities of any individuals who received funds from the proceeds have not been publicly reported. Earlier this month, however, six members of the J6 Prisoner Choir were identified in Special Counsel Jack Smith’s final report on Trump’s 2020 election interference case. The special counsel’s list of the choir members includes Julian Khater, Jorden Mink, Ronald Sandlin, Barton Shively, and James McGrew. Prior to being pardoned by Trump, all six of the men pleaded guilty to assaulting law enforcement officers on Jan. 6.

The Classified Documents Case

In 2022, after media reports revealed that Trump had retained documents marked classified after he left office, the former president suggested that he had declassified the materials during his time in office.

In May of that year, as the Justice Department’s criminal investigation heated up, Patel began laying the groundwork for a potential “declassification” defense. In an interview with the conservative outlet Breitbart, he said that news reports about Trump’s retention of classified material were misleading. “The White House counsel failed to generate the paperwork to change the classification markings, but that doesn’t mean the information wasn’t declassified,” Patel said. “I was there with President Trump when he said, ‘We are declassifying this information.’”

Later, in an interview on Fox News, Patel told host Mark Levin that he had witnessed Trump declassify “whole sets of documents” shortly before he left office. Patel repeats this claim in his book, stating that Trump “declassified whole sets of documents, including every single document relating to Russia Gate and to the Hillary Clinton scandal.”

Later, when the FBI submitted a warrant application to search for additional documents at Mar- a-Lago, the accompanying affidavit flagged Patel’s public assertions regarding declassification. Patel, who has claimed that the FBI’s search at Mar-a-Lago was carried out for the purpose of getting “those Russia Gate documents and other material back under lock and key,” viewed the inclusion of his name in the warrant affidavit as an intentional “smear.”

“The people who executed the Russia Gate scandal were taking their revenge on one of the main people who exposed their lies in an attempt to scare me and anyone else who would dare contradict them,” Patel asserts in his book.

There appears to be no credible evidence to support Patel’s claim that Trump declassified the documents found at Mar-a-Lago prior to his departure from the White House. Though Trump’s lawyers advanced the legal argument that he had absolute power to declassify information during his tenure in office, the claim that he did in fact do so remained conspicuously absent from his defense team’s filings.

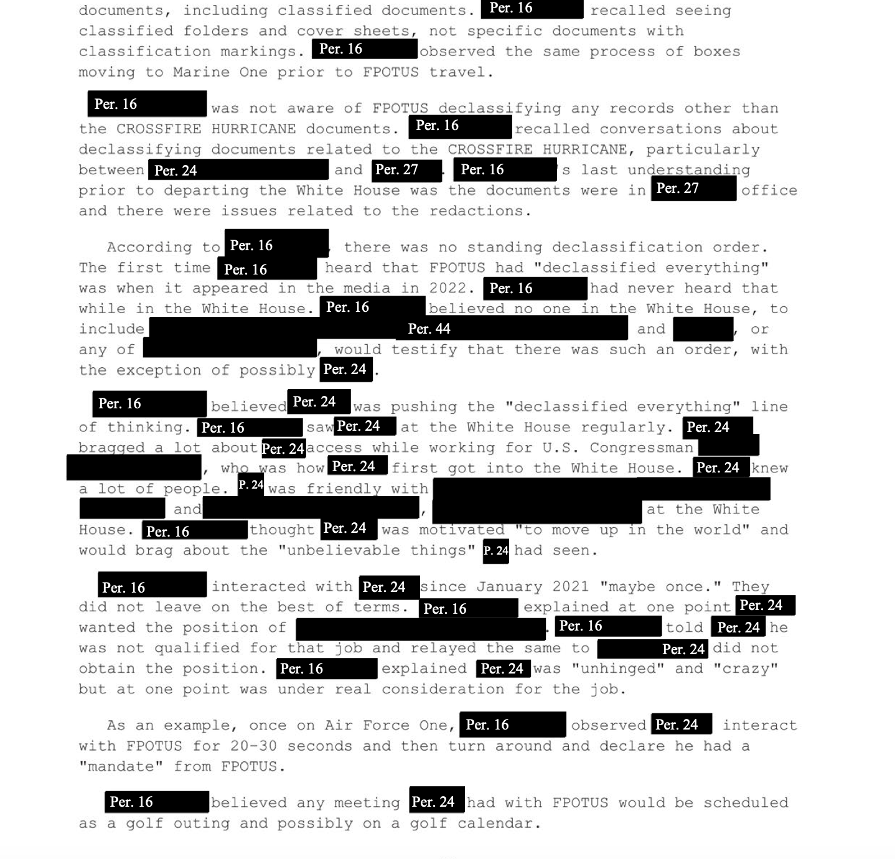

Meanwhile, two of Trump’s top advisers during his time at the White House—former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows and former Vice President Mike Pence—have said that they were unaware of any widespread declassification of documents before Trump departed. Another witness in the case, identified as “Person 16” in redacted court documents, told the FBI that there “was no standing declassification order.” Person 16 didn’t believe that anyone in the White House would testify that there was such an order, with the exception of one person: “Person 24,” who is described as someone who bragged a lot about “access” while working for a United States Congressman. Person 16 believed that Person 24 was “pushing” the “declassified everything” line of thinking, according to the court filings.

While it is true that Trump declassified portions of a binder containing material related to the Russia investigation in January 2021, the binder was reportedly not among the materials seized at Mar-a-Lago. As for Patel’s claims that the FBI’s search at Mar-a-Lago was engineered to recover “Russia Gate” documents, a U.S. official told CNN in 2023 that the FBI was not looking specifically for intelligence related to Russia when it obtained the search warrant for the former president’s residence.

What’s more, at least one of the documents charged in Trump’s classified documents indictment would not be subject to automatic declassification by the president. In the indictment, Document 19 is described as “formerly restricted data” concerning United States nuclear capabilities. As Matt Tait has explained for Lawfare, “formerly restricted” data is classified by virtue of a statute, the Atomic Energy Act, meaning that Trump could not have directly declassified the document even while president.

Patel’s involvement in the classified documents case did not end with his Breitbart interview about Trump’s supposed mass declassification. In June 2022—one month after the Breitbart interview—Trump designated Patel and John Solomon, a conservative journalist, as his representatives to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

In a string of interviews on right-wing shows later that month, Patel again claimed that Trump had declassified swaths of “Russia Gate” documents in the waning days of his administration. But, according to Patel, the White House counsel’s office had blocked the release of those documents and, instead, delivered them to NARA. Patel said that Trump asked him to use his status as his NARA representative to access and release documents to the public. “I can tell you now that I am now officially a representative for Donald Trump at the National Archives,” he said. “And I’m going to march down there—I’ve never told anyone this, because it just happened—and I’m going to identify every single document that they blocked from being declassified at the National Archives and we are going to start putting that information out next week.”

According to emails filed in a civil suit, Patel and Solomon pressed NARA’s general counsel, Gary Stern, for access to the “binder of documents” related to the Russia investigation, parts of which had been declassified by Trump before he left office. Stern responded by telling Solomon and Patel that the agency did not receive the “binder” described by Solomon, though it did receive some copies of documents pertaining to the Russia investigation. The problem, Stern explained, was that there remained considerable “uncertainty” over the status of classified information in the documents.

Patel insisted that he should nonetheless be allowed to review the documents, citing his active security clearance. In response, Stern said that his “personnel security office” could not find an active clearance for Patel in their systems.

It remains unclear whether Patel’s clearance was confirmed by NARA. (As previously noted, a “flag” was placed in Patel’s security clearance file after the CIA referred him for criminal investigation related to his handling of classified information in 2020. The flag remains on Patel’s file inside the FBI’s clearance database, CNN reports.)

Solomon, for his part, later sued the National Archives and the Justice Department, claiming that they had unlawfully blocked access to the documents.

The timing of Patel’s crusade against NARA was peculiar. Earlier that year, in January 2022, NARA officials discovered classified documents in 15 boxes of presidential records that had been returned by Trump after being “improperly” removed to Mar-a-Lago following Trump’s departure from the White House. The agency subsequently referred the matter to the Justice Department for criminal investigation, and a federal grand jury investigation began in April 2022. As part of this latter investigation, the grand jury issued a subpoena on May 11, 2022, seeking the production of all documents with classification markings in Trump’s possession. In a number of respects, how Trump and his staff responded to this subpoena during the summer of 2022 forms the gravamen of much of the criminal conduct alleged in the indictment, culminating in the search at Mar-a-Lago on Aug. 8, 2022. All of which coincided with Patel’s sudden claims about mass declassification and his appointment as Trump’s NARA representative.

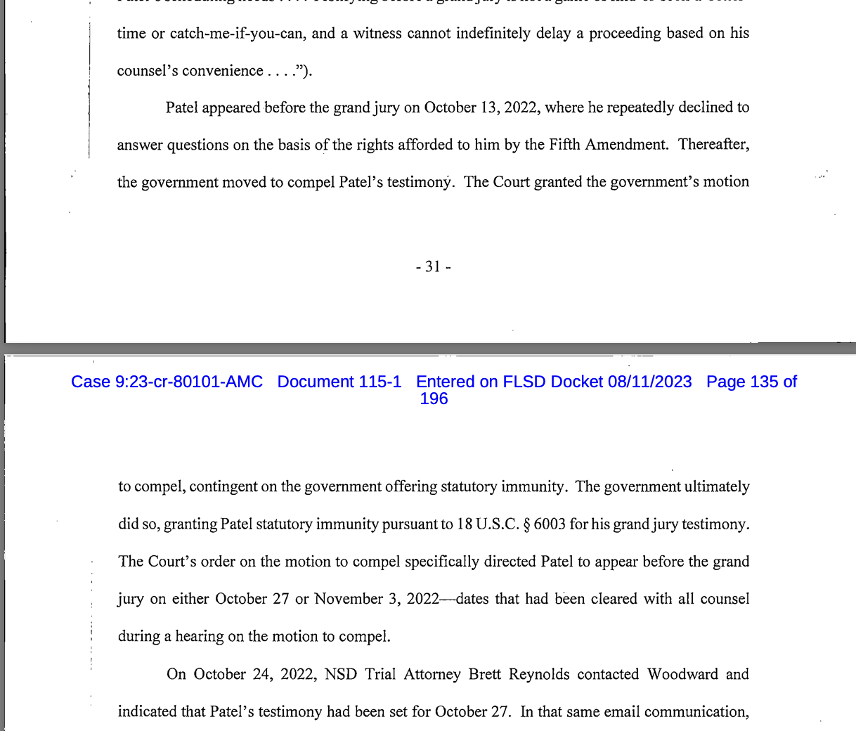

It’s no surprise, then, that the government summoned Patel to testify before a grand jury in the documents case later that year. According to a court filing, Patel was represented by Stanley Woodward, who at the time also represented Trump’s future co-defendant, Walt Nauta. During Patel’s first appearance, in October 2022, he declined to answer questions, citing his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. Prosecutors eventually compelled Patel’s testimony by offering him a grant of immunity.

Earlier this week, on Jan. 29, Democratic members of the Senate Judiciary Committee sent a letter to Acting Attorney General James McHenry, requesting access to review Special Counsel Jack Smith’s final report on Trump’s classified documents case.

“Mr. Patel’s testimony under oath before the grand jury on this and other potential matters, and the Special Counsel’s findings with regard to Mr. Patel’s related activities and statements, remain unknown to the Committee and the public,” the letter said. “The Committee cannot adequately fulfill its constitutional duty without reviewing details in the report of Mr. Patel’s testimony under oath,” it continued.

Judge Aileen Cannon previously blocked Attorney General Merrick Garland’s plan to allow members of Congress to review the report regarding the classified documents case. At the time of this writing, the report remains under injunction by order of Judge Cannon.

Retribution

Patel’s history of threatening retribution against Trump’s enemies, and his own, is a long one.

There is, for starters, the list that appears in Appendix B of Government Gangsters, entitled “Members of the Executive Branch Deep State.” Many commentators have dubbed the list an “enemies list,” a characterization Attorney General nominee Pam Bondi disputed in her hearing before the Judiciary Committee. Patel does not say in the book precisely what the list is or what should happen to the people on it, save that it’s a non-exhaustive list of members of the “Deep State.” According to Patel, the “Deep State” refers to “a cabal of unelected tyrants who think they should determine who the American people can and cannot elect as president, who think they get to decide what the president can and cannot do, and who believe they have the right to choose what the American people can and cannot know.”

He also says the list does not include “other corrupt actors of the first order such as Congressmen Adam Schiff and Eric Swalwell, members of Fusion GPS or Perkins Coie, Christopher Steele, Paul Ryan, the entire fake news mafia press corps, etc.”

It’s safe to say that Patel does not wish well for the people who are on the list, which includes, among others, former Attorney General Bill Barr, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, former FBI Director James Comey, former Secretary of Defense Mark Esper, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley, and former FBI Director Christopher Wray.

Elsewhere, he has been more explicit about investigating and prosecuting those who have run afoul of the president. During an appearance on Steve Bannon’s “War Room,” Patel said that he wanted to go after perceived enemies “not just in government but in the media.”

“We’re going to come after the people in the media who lied about American citizens who helped Joe Biden rig presidential elections,” Patel said, referring to the 2020 election. “We’re going to come after you, whether it’s criminally or civilly…We’re putting you all on notice.”

Perhaps the oddest of Patel’s promises of politicized law enforcement appears in one of his children’s books, The Plot Against the King 3: The Return of the King. In this fairy tale, the dragon is actually named “DOJ.” In the story, the dragon is tricked into attacking “King Donald.” But the king and his wizard named “Kash” violently subdue the dragon and then train him to go after Trump’s enemies instead.

Reforming the FBI

“Things are bad. There’s no denying it.”

So begins Patel’s assessment of the current state of the federal investigatory agency he would lead, if confirmed by the Senate. In Patel’s view, the FBI is “now the prime functionary of the Deep State.” As he explains it: “The politicized leadership at the very top has turned it into a tool of surveillance and suppression of American citizens.”

What, then, would Patel do to turn things around? He has some ideas, which he recounts at length in Appendix A of his book, titled “Top Reforms to Defeat the Deep State.” Among the reforms suggested by Patel:

Move the FBI headquarters out of Washington. “Whether through Congress or the President, the FBI headquarters should be removed from Washington, D.C., to prevent institutional capture and curb FBI leadership from engaging in political gamesmanship,” he writes. Patel repeated a more extreme version of this proposal as recently as September, during an interview on The Shawn Ryan Show. “I’d shut down the FBI Hoover Building on day one and reopen it the next day as a museum of the ‘deep state,’” he said. “Then, I’d take the 7,000 employees that work in that building and send them across America to chase down criminals. Go be cops. You’re cops — go be cops.”

Cut the Office of the General Counsel. Patel writes that the scope of the FBI’s authority must be “dramatically limited and refocused.” To accomplish this goal, he continues, one “practical reform” that can be implemented would be to cut or reduce the size of the FBI’s Office of General Counsel. “Instead of operating as a purely investigatory body, the General Counsel office within the FBI has taken on prosecutorial decision-making,” Patel argues in Government Gangsters. “In effect, they are centralizing power to both investigate and prosecute crimes, even though it is the job of Department of Justice alone to prosecute crimes. The General Counsel office should be significantly reduced in size.” As one example of the supposed overreach of the FBI’s Office of the General Counsel, Patel cites the fact that the FBI General Counsel certified the FISA warrants that were used, as he puts it, “to spy on the Trump campaign” during the 2016 Russia investigation.

Fire the top ranks of the FBI. “The next President must fire the top ranks of the FBI,” Patel writes. “Then, all those who manipulated evidence, hid exculpatory information, or in any way abused their authority for political ends must be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. The only way to stop the corruption is to make it abundantly clear that corruption has consequences,” he explains.

Increase congressional oversight. Patel has further suggested that Congress has a key role to play in ensuring that government officials are held accountable for their actions. Patel has endorsed tactics like “fencing,” which involves Congress withholding a portion of funds to induce “corrupt officials” to comply with document demands and requests for testimony before Congress. “You ground Chris Wray's private jet that he pays for with taxpayer dollars to hop around the country. You take away the fancy new fleet of cars from DOJ that they’re going to use to shuffle around executives,” he explained on an episode of “Kash’s Corner” in 2023. It remains to be seen whether Patel would endorse the same practice if the shoe were on the other foot. How would a Director Patel react if Congressional Democrats grounded his taxpayer funded jet?

Ban jurisdiction shopping. Patel proposes that both the FBI and the Justice Department should be “banned from jurisdiction shopping” and that “policies should be implemented to ensure truly blind jurisdiction choices.” This reform appears to be informed by his belief that “jurisdiction shopping allowed corrupt FBI agents to leverage a highly biased federal judge in order to secure the search warrant to raid Mar-a-Lago.” (In reality, there’s no evidence of such “jurisdiction shopping” in relation to the Mar-a-Lago search. The FBI sought the warrant in the jurisdiction in which the property was searched and in which charges were eventually brought. As in all cases, the magistrate judge who signed the warrant, Bruce Reinhart, would have been assigned at random.)

As a part of his proposal to curb “jurisdiction shopping” by the FBI and the Justice Department, Patel has also suggested that the Attorney General should reduce the number of trials prosecuted in Washington, D.C. “In 2020, Washington, DC, voted 92 percent for Joe Biden and less than 6 percent for Donald Trump,” he explains. For that reason, Patel continues, federal prosecutors must “cease prosecuting trials in a place with such a biased jury pool unless it is absolutely necessary.”

FISA Reforms

In Government Gangsters, Patel saves his most ardent proposals for the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), a matter senators will want to consider given the FBI’s primary responsibility for implementing FISA and the fact that Section 702 of the law will come up for renewal—yet again—in the first two years of his terms of service. In Patel’s view, the current structure of FISA is a “recipe for abuse”—though he admits that, as a former terrorism prosecutor, FISA can be useful. So while Patel doesn’t want to get rid of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) altogether, he contends that there is a great need for “decisive reforms.” The reforms proposed by Patel include the following:

Install properly trained, long-term judges to the FISA Court. Under current law, the FISC is composed of 11 federal district judges who are designated by the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court to fulfill this part-time judicial assignment. Though many FISA judges serve on the court for several years, a judge typically sits “on duty” for one week at a time, on a rotating basis. In Government Gangsters, Patel takes issue with this structure, griping that “every month a new judge walks in who has no background on the cases before them and sometimes little to no knowledge of national security or counterterrorism law.” As a result, Patel claims, the vast majority of warrants are approved with a “literal rubber stamp.” (In support of this claim, Patel cites an article from a right-wing website, The Daily Caller. The article does not say how the FISA warrant approval rates compare to non-FISA warrants, which are also approved almost always.) All of which leads Patel to the conclusion that the FISC needs “properly trained, long-term judges.” He doesn’t elaborate on how such judges ought to be selected or trained.

Implement a Public Defender-like Role at the FISC. “The FISA court should have standing public defenders who act as advocates for the accused, picking apart the prosecution’s case, demanding to see the source evidence, and confronting the prosecutor for any Brady violations,” Patel writes. According to Patel, the presence of a public defender-like role at the FISC could have prevented many, if not all, of the “unlawful search warrants” used to “spy” on Trump campaign during the Russia investigation, because “somebody would have been there to poke holes in the Steele Dossier” and to “call the FBI out on their bull.”

Install a court reporter at the FISC. Patel points out that there is no standing court reporter to transcribe proceedings that occur before the FISA court. “This must change overnight. Every single hearing must be transcribed to the written record during the proceedings,” Patel stresses. “How else are we supposed to correct the wrongs of the past if we don’t know what happened?”

Patel doesn’t mention Rule 17 of the FISC Rules of Procedure, which states as follows: “A Judge may take testimony under oath and receive other evidence. The testimony may be recorded electronically or as the Judge may otherwise direct, consistent with the security measures referenced in Rule 3.”

Establish a team of non-partisan national security lawyers to check warrants. Patel suggests that FISA warrants need to be “randomly checked by a team of seasoned, experienced, nonpartisan national security lawyers who report directly to the White House or the attorney general.” The lawyers would serve for short terms, according to Patel, in order to “prevent institutional capture.” While Patel provides few details about what the review process would involve or who would have the final say, he lists a number of questions that the lawyers would be tasked with asking in the course of their review: “Why was this warrant allowed and not this one? What is the source evidence for this claim? Did you hide any exculpatory evidence? What is the verification for the source, as well as his or her bias and political leanings?”

The Poodle Room

While little is known about Patel’s personal life, the New York Times reports that he lives in Las Vegas, where he was recently accepted as a member of a private rooftop club called The Poodle Room. Membership in The Poodle Room, located on the eighty-ninth floor of the Fontainebleau resort, costs an estimated $20,000 per year. Put differently, that’s approximately 500 “Fight with K$H” Americana flags.