The Situation: Contempt Cometh

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The Situation on Wednesday offered a “Liberation Day” paean to “Invasion of the Body Snatchers.”

Today, let’s discuss whether the federal courts have what it takes to enforce their orders.

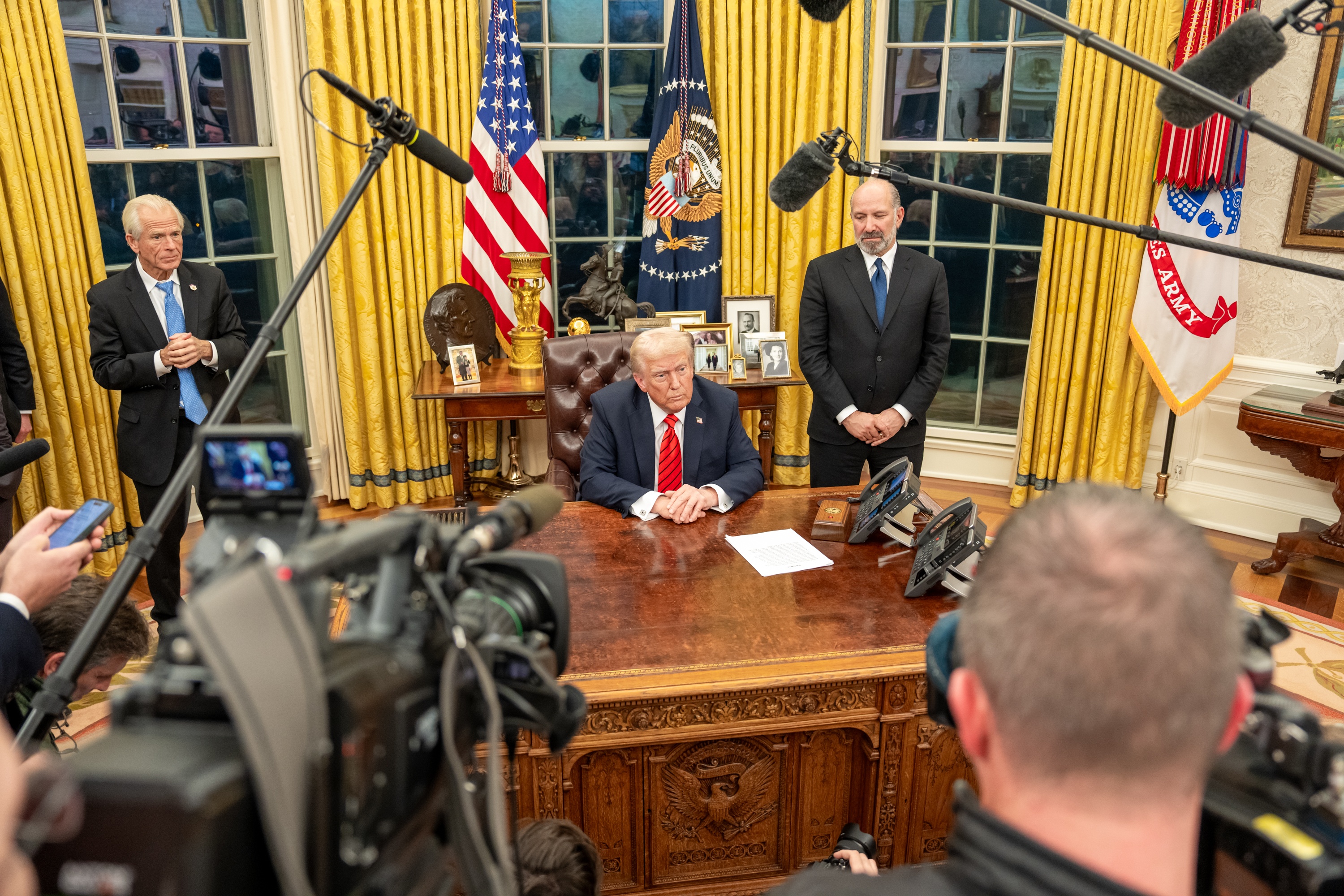

Talking about defying court orders is all the rage these days. It’s a common lament in Washington that President Trump might choose to just blow through any court orders that inconvenience him, and that the Supreme Court—out of fear of his defiance—will hesitate to order anything that may trigger his noncompliance.

Well, folks, we have a test case on our hands, one that should give us a good window into whether the courts are able to hold the administration to the law. It’s a case in which the defiance of a court’s order was blatant and pretty obviously willful and in which the judge seems bent on figuring out exactly what happened and who is responsible.

On April 3, in a courtroom in Washington, an unfortunate soul named Drew Ensign—on behalf of the Trump administration—appeared in front of Chief Judge James Boasberg to explain why someone in the government should not be held in contempt for violating the judge’s order to turn around planes deporting Venezuelan migrants to El Salvador pursuant to the president’s proclamation under the Alien Enemies Act.

Judge Boasberg began by getting Ensign to admit certain things the administration is denying out of court:

The order in question didn’t require the release of any gang members.

It didn’t prevent the detention in immigration proceedings of any additional gang members.

It didn’t prevent the deportation of any gang members pursuant to normal immigration procedures.

In fact, the administration had done just that with respect to Tren de Aragua members.

All the temporary restraining orders did was to prevent the government from “summarily deport[ing] in-custody noncitizens who were subject to the proclamation without a hearing.”

“So if anyone in the administration continues to make statements that are contrary to what I have just said, those statements would not be truthful, isn't that right?” the judge asked. “Those facts that we have just agreed on, they wouldn't be true?”

Ensign responded tautologically: “Yes, Your Honor. To the extent that it's contrary to things that are true, they would be false.”

“They would, indeed,” said Judge Boasberg.

Having gotten the Trump administration to admit—perhaps for the first time—that things that are false are not true, Judge Boasberg proceeded to elicit from Ensign a timeline of the events in question. Specifically, Ensign affirmed that he believed the president’s proclamation was signed on March 14, though it wasn’t made public until March 15 and though President Trump later said he hadn’t signed it at all. The date matters because lawyers for the detainees started hearing about the proclamation before it was released and brought their suit based on what they had heard—filing in the wee hours of the morning of March 15. The timing raises the question of whether the government kept the proclamation secret while they rounded people up to avoid litigation that might halt the flights.

Judge Boasberg then got Ensign to concede that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement must have known about the proclamation before it was made public at 3:53 p.m. on March 15, since it had already begun readying planeloads of detainees for removal. By that point, the judge had already scheduled a hearing for 5:00 p.m. that day.

The judge asked why he should not conclude that the government had raced to fill three planes with detainees and get them off the ground before he could enjoin it. Ensign had no plausible answer. The judge then also asked whether, when Ensign said at that hearing that he did not know whether any removals were planned over the next 24 hours, he knew that planes had already taken off:

BOASBERG: So what I want to know here, as an officer of the court, you are telling me that you had no knowledge whatsoever between 5:00 and 6:00 p.m. on that day that planes were in the air or shortly would be in the air? You had no knowledge whatsoever of that?

ENSIGN: Your Honor, I had no knowledge from my client that that was the case. I had knowledge from plaintiffs' submissions to the Court that that might have been occurring. I can also assure you, as an officer of the Court, I diligently tried to obtain that information but was not able to do so.

Judge Boasberg made clear that he did not believe Ensign had lied to him, so he turned to learning who had defied the order. Under further questioning, Ensign named several people at the Justice Department to whom he had relayed news of the order. He also conceded that he had told informed officials at the Department of Homeland Security and the State Department.

“So who then gave the order that the planes should not turn around?” the judge asked. “Again, you have said that it was perfectly appropriate for the government to act as it did. So who made that perfectly appropriate decision?”

Responded Ensign: “Your Honor, I don't know that.”

BOASBERG: What were you told?

ENSIGN: Your Honor, I haven't been told.

BOASBERG: So you, standing here, have no idea who made the decision to not bring the planes back or have the passengers not be disembarked upon arrival?

ENSIGN: Your Honor, I do not know those operational details.

Having established that Ensign was not going to be able to furnish him with the name of the responsible party, Judge Boasberg made clear that the matter would not end there: “If I don't agree, I don't find your legal arguments convincing and I believe there is probable cause to find contempt, what I am asking is, how should I determine who the contemnor or contemnors are?”

Judge Boasberg had another question for Ensign: Assuming he finds that the government violated his order, does the government want an opportunity to purge the contempt—and has he given any thought to how it might do so, other than with the return of at least two planeloads of people?

The judge ended the hearing by declaring that he wouldn’t rule on this matter until next week. But it seems like he is spending the weekend writing a ruling laying out the factual record—which is damning—finding probable cause for a contempt order, and ordering sworn testimony of one sort or another as to who defied him.

This is how the courts work when they are functioning well. No, they are not fast by the standards of news and politics. Yes, a fair bit of time will have gone by between the moment everyone knew the administration had defied this order and the time that Judge Boasberg can assemble the detailed record that will demonstrate that reality.

But good judges are methodical. They proceed carefully. And they proceed rigorously and with attention to what they can document. And at the end of this process, Judge Boasberg seems very likely to hold someone in contempt, offer him or her the opportunity to purge that contempt, and then take some action to force that person to rectify the situation.

The real question, when we think about whether the courts can hold Trump to the law is whether this process can proceed with integrity, whether Judge Boasberg can identify the person who caused those plans to proceed despite his order, whether he can fashion some coercive measure that has teeth against that person, and whether the appellate courts will back him.

I will say three things at this preliminary stage of this confrontation:

First, I would not have wanted to be Drew Ensign in Thursday’s hearing.

Second, Judge Boasberg is clearly determined to get to ground truth about what happened and enforce his order.

And third, I wouldn’t bet against him.

The Situation continues tomorrow.