The Situation: Court Orders, Kidnapping, and Smuggling

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The Situation on Friday asserted that “it’s going to take a lot of work” for U.S. District Judge Paula Xinis and her colleagues on the federal bench to get a recalcitrant executive branch to comply with court orders. “Everything they order will require follow-up—which sometimes will take a lot of time. Every statement the government makes has to be verifiable—and verified. Every factual representation will require an affiant who is under oath or maybe even a live witness. Some individual person has to be accountable for every single statement.”

A fair bit of water has flowed under the bridge since I wrote these words three days ago. All of the events that have post-dated the column have reinforced this point.

Let’s review the bidding:

When I wrote Friday’s column, Judge Xinis had ordered daily status updates from the government because she had previously ordered it to outline the steps it had taken to secure the release of Kilmar Abrego Garcia from a Salvadoran gulag and it hadn’t bothered to do so. She wrote:

[T]he Court had directed Defendants to file a supplemental declaration from an individual with personal knowledge, addressing the following: (1) the current physical location and custodial status of Abrego Garcia; (2) what steps, if any, Defendants have taken to facilitate Abrego Garcia’s immediate return to the United States; and (3) what additional steps Defendants will take, and when, to facilitate his return. Defendants made no meaningful effort to comply.

In response, the judge required that the government file daily by 5:00 p.m. “a declaration made by an individual with personal knowledge as to any information regarding”: (1) Abrego Garcia’s location and custodial status, (2) what steps have been taken to have him returned, and (3) what additional steps are planned and when they are planned for.

Speaking aboard Air Force One that same day, Trump declared: “If the Supreme Court said bring somebody back, I would do that. I respect the Supreme Court.” He seemed unaware that the Supreme Court had only days earlier said he should “facilitate” exactly that.

On Saturday, the government gave Judge Xinis its first declaration under her order. It came from a State Department official named Michael Kozak and appears not to address at least two—and maybe three—of the four components of Xinis’s order. It gives exactly zero information about what steps the government has taken or has planned to get Abrego Garcia back.

Nor is it obvious that Kozak is “an individual with personal knowledge” of the situation. Kozak’s declaration says it is offered “based on my personal knowledge, reasonable inquiry, and information obtained from other State Department employees.” But Kozak attributes the only substantive information he provides not to his personal knowledge but to “official reporting from our Embassy in San Salvador.”

That substantive information is limited to the fact that Abrego Garcia is alive and being held at the “Terrorism Confinement Center” pursuant to the “sovereign, domestic authority of El Salvador.” This language is code for the notion that the United States is now powerless to get him back because some other sovereign holds him.

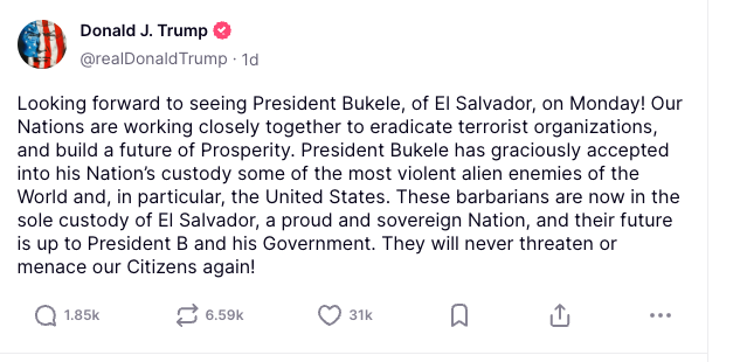

Trump seemed to back this up the following day, in a tweet on Truth Social in which he declared that the deported “barbarians are now in the sole custody of El Salvador, a proud and sovereign Nation, and their future is up to President B[ukele] and his Government”:

Trump neglected to mention that the United States is reportedly paying El Salvador to exercise its sovereignty in this fashion.

Sunday’s “status report” offered no new information. This one took the form of a declaration by one Evan C. Katz, assistant director for the Removal Division of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). He recited the procedural history of the case, all of which Judge Xinis knows very well, but his substantive input was limited to the following illuminating contribution: “It is my understanding that Defendants have no updates for the Court beyond what was provided yesterday.”

The government followed up with a brief insisting that any further inquiry into its conduct would be an outrageous intrusion on the executive branch’s responsibility for conducting foreign policy and that it was in full compliance with the Supreme Court’s order that it “facilitate” Abrego Garcia’s return. The government also complained that Xinis was “directing Defendants to submit sworn testimony revealing sensitive information and previewing nonfinal, unvetted diplomatic strategies.” And it stated that plaintiffs were calling “for the immediate production of classified documents, as well as documents that Defendants may elect to assert are subject to the protections of attorney-client privilege and the State Secrets privilege.”

Then, this morning, White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller went on Fox News and denied—contrary to the Justice Department’s repeated representations in court—that Abrego Garcia had been erroneously deported. Miller insisted that retrieving him would amount to a “kidnapping” and said the Supreme Court had ruled unanimously in the administration’s favor on the matter.

To cap things off, Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele showed up at the White House today and declared that he had no power to “smuggle a terrorist into the United States” and that he wasn’t going to try. (Trump also said to Bukele that “homegrowns are next” and urged him to build more prison spaces—which appears to refer to U.S. criminals.)

It’s like a game of three-card monte. Trump says it’s all up to Bukele. Bukele says it’s all up to Trump. And under card number three, a federal judge has to somehow protect all of our rights not to be disappeared into a foreign gulag.

So how does a reasonable federal judge respond to such committedly proud lawlessness and lying?

It’s a hard question.

And Judge Xinis has certain significant handicaps in undertaking a confrontation with the president. The first is that she doesn’t, in fact, control the foreign policy apparatus of the United States. Our embassy in San Salvador represents Trump, not her. Our State Department does too. When the Salvadoran president meets with the American administration, he talks to Trump, not the judge. And when he gets asked whether he will send Abrego Garcia back, he’s sitting next to Trump. He’s not in Judge Xinis’s court.

What’s more, as the press conference with the two presidents showed, Trump is not inclined to exercise those foreign policy powers on behalf of Abrego Garcia. He used his public time with Bukele to have Attorney General Pam Bondi and Miller both spread wild mischaracterizations of the case and of the Supreme Court’s holding, and to bask in Bukele’s refusal to “smuggle” Abrego Garcia back into the United States. It’s very clear that Trump has no inclination to use his foreign policy powers in a fashion that will remedy the erroneous deportation.

The second problem for the judge is that it is not clear how far the judge can go and still have the backing of the Supreme Court. The court ruled unanimously that she was within her power to order the executive to “facilitate” Abrego Garcia’s return and that the administration “should be prepared to share what it can concerning the steps it has taken and the prospect of further steps” to get Abrego Garcia back.

But it also said that the judge needs to proceed “with due regard for the deference owed to the Executive Branch in the conduct of foreign affairs.” How will the Supreme Court understand what that “due regard” looks like and what information the administration “can” share concerning the steps it is or isn’t taking on Abrego Garcia’s behalf? That’s unclear. So the judge doesn’t know how much latitude she has here to be aggressive with officials who are playing hardball with her.

Third, Judge Xinis will have to think hard about whether and how she can enforce whatever orders she issues. Normally, court orders are enforced by the threat of civil contempt, which can result in fines or incarceration of recalcitrant subjects. But this is a tricky tool to use when the executive branch—or its officials—are the contemnors.

After all, it is the executive branch that locks people up and presumably won’t do so to its own officials effectuating presidential will. And fines can be reimbursed.

Besides, Judge Xinis still doesn’t know who the contemnor is here. Like Judge James Boasberg a couple of weeks ago, she knows her order has been flouted, and she knows it has been flouted by the government, but an order works best when it names a specific person or entity and imposes a coercive pressure targeted at that person or entity.

So how does Judge Xinis play her hand—a hand that is overpoweringly strong in a moral sense and in terms of the legal wrong that has been done to Abrego Garcia but which is institutionally weak relative to that of a president who cares about the law no more than he cares about justice?

I have a few suggestions—none of them a magic bullet.

The first step is to insist that the administration’s minimalist conception of the Supreme Court ruling is a nonstarter. Both the White House and the Justice Department talk as though—as the Justice Department put it one brief—the word “facilitate” means only what the:

term has long meant in the immigration context, namely actions allowing an alien to enter the United States. Taking “all available steps to facilitate” the return of Abrego Garcia is thus best read as taking all available steps to remove any domestic obstacles that would otherwise impede the alien’s ability to return here. Indeed, no other reading of “facilitate” is tenable—or constitutional—here.

In other words, the administration’s position is that the Supreme Court has imposed no duty on it to get Abrego Garcia back from El Salvador, merely a duty not to reject him if he happens to show up at a port of entry. The first step is to reject this view, and to make clear that the court expects the government to take affirmative steps to seek Abrego Garcia’s return from the Salvadoran government. This shouldn’t be too hard, since the Supreme Court’s opinion specifically said that her “order [had] properly require[d] the Government to 'facilitate' Abrego Garcia’s release from custody in El Salvador” (emphasis added), not merely that it deal with “domestic obstacles.”

The second step is to create a record. Lawyers for Abrego Garcia have asked for discovery on what steps the government has taken, and the Supreme Court has given the go-ahead for limited inquiry into what the government is doing and has done. This gives Judge Xinis some room to force testimony by individuals actively involved in the matter and to try to identify whether any steps are actually being taken to secure his freedom or whether the administration is simply defying her. She might start by ordering the testimony of the individuals whose declarations the department has filed to determine how they know what’s in those declarations and whether their knowledge is, in fact, firsthand.

Third, while enforcing her order against the Department of Homeland Security and the State Department—not to mention the White House—is hard, there is one party over which she has more direct control: the Justice Department attorneys who appear before her. The department has seemingly made a point of filing documents late. It has, as shown above, also made a point of not addressing the questions she has posed. At some point, the contempt becomes not merely that of the client agencies but that of the lawyers who are filing these documents. Lawyers are easier to sanction than federal agencies, as they are officers of the court and subject to immediate court discipline.

Fourth, the key task here is to make the government justify every refusal to answer a reasonable question, and to make clear where precisely that refusal is coming from. If the government won’t say why it can’t disclose the terms of our deal with the Salvadorans to lock up deportees, make clear who is invoking that and why. If it won’t tell what steps it has taken, make clear whose decision that silence is and what the basis is for it.

The goal is to either get the truth or force the government to appeal on the basis of unfavorable facts.

Ultimately, the ambition here is to home in on a very specific set of questions: Who was the decision-maker, or who were the decision-makers? And what precisely did that person or group of people decide in response to Judge Xinis’s original order, in response to the Supreme Court’s decision, and in response to Judge Xinis’s various orders in its wake?

The remedy, if there is one, will flow from the answer to these questions.

The Situation continues tomorrow.