The Situation: Horsepeople of the Trumpocalypse

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The Situation on Thursday asked readers to consume news about, well, The Situation more slowly, more deliberatively.

This week is going to test that. The news is going to come fast and furious. In particular, the nominations news will be hitting hard:

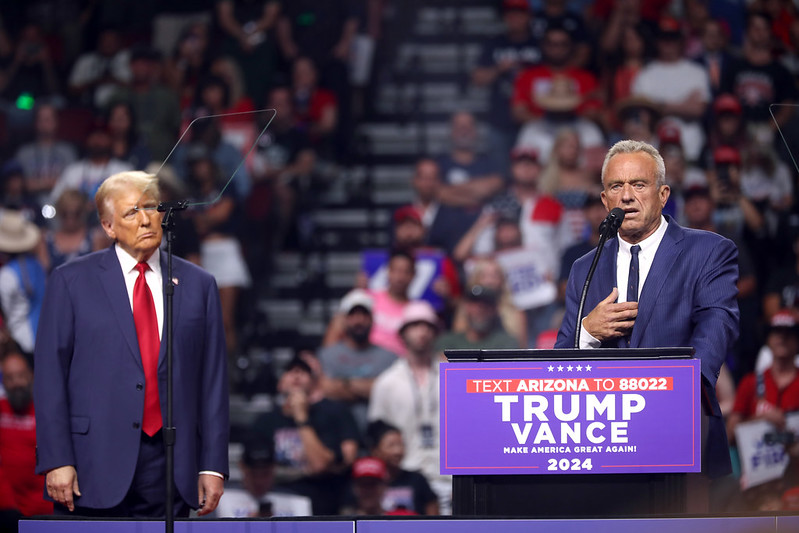

- Wednesday will see a hearing for Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to be secretary of health and human services;

- Thursday will see one for Tulsi Gabbard to be director of national intelligence;

- And the same day, Kash Patel will appear before the Senate Judiciary Committee as the president’s nominee to run the FBI.

These are three of President Trump’s most manifestly unfit nominees, three of the four horsepeople of the Trumpocalpyse.

The fourth horseman, Pete Hegseth, was confirmed Friday night to be secretary of defense.

The signs in the Hegseth story for the other horsefolk are frankly mixed. On the one hand, Hegseth got confirmed, despite being wholly unqualified for the job, despite credible sexual assault and alcohol abuse allegations against him, and despite harboring attitudes concerning women in combat units (he’s against them) and war crimes (he’s for them) that are hard to square with the modern Department of Defense.

On the other hand, Hegseth’s confirmation vote was encouraging in important respects. Republicans, despite a 53-seat majority in the Senate, required Vice President Vance to break a tie vote. That’s because three Republican senators, including former Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, voted against the nominee. And this creates a baseline that has to make comparably unfit fellow-nominees—and their White House patrons—at least a little bit nervous.

To make matters more complicated, there is no such thing as two “comparably unfit” nominees. As Tolstoy might put it, all qualified nominees are the same. All unqualified nominees are unqualified in their own unique fashions.

To wit, none of this week’s candidates seems to have Hegseth’s unique personal toxicity. In other ways, however, they may each be worse nominees than Hegseth, who actually did a reasonable job during his hearing presenting himself and buffaloed his way past any number of questions concerning his personal conduct. Any of these nominees could crash and burn at a hearing. Besides, is leaving a bear cub carcass in Central Park and opposing vaccines better or worse than being accused of sexual assault while cheating on a succession of wives and vouching for war criminals? The fact that Hegseth could barely get through the Senate after doing pretty well before the Armed Services Committee suggests that there may be room to stop at least some of the nominees the Senate will hear from this week.

All of which makes this a week of no small moment. The public has already learned that the Senate is too afraid of Trump to stop a TV show host whom colleagues insist showed up drunk for work from taking the helm of the Pentagon. This week we will find out just how deep the Senate’s fearfulness before Trump goes. Does it have a bottom at all?

The three nominees present different problems. Patel’s nomination represents the open and proud politicization of law enforcement. Gabbard’s represents the Trumpian embrace of dictators, credulity before foreign propaganda, and suspicion of inconvenient intelligence; her inability to account for her meetings with Bashar al-Assad is genuinely peculiar. Kennedy, for his part, represents the rejection of mainstream health sciences and the suspicion of modern medicine and its progress against infectious disease.

But there is an important common thread linking these nominees: All three of the remaining horsepeople believe important things that simply are not true—or refuse to believe important things that are.

In Patel’s case, the fantasizing concerns plots against Donald Trump—about which he has written children’s books. He believes the 2020 election was stolen from Trump, for example.

Kennedy, for his part, believes that vaccines cause autism, that COVID was targeted at Black and white people and that Asians and Ashkenazi Jews have high immunity, and that fluoridated water is associated with all sorts of health maladies.

And Gabbard has publicly cast doubt on the Syrian government’s responsibility for chemical weapons attacks on civilians and has argued that U.S. funded “biolabs” are all over Ukraine.

They all, in other words, believe total nonsense.

These are not classic politician lies—not akin, for example, to Hegseth’s denials at his hearing that he had been blackout drunk in professional settings. They don’t involve the personal conduct of the nominees.

They involve, rather, belief systems, views of reality. Voting against such a nominee is therefore not a matter of adjudging the morality or propriety of the person’s conduct—though one might do that as well—so much as it is a matter of determining that they are just a little too nutty to hold office.

Our society takes a complicated view of evidenceless beliefs on the part of leaders. On the one hand, the Constitution protects religious freedom and specifically bans religious tests for public appointment, which means that at a certain level of altitude, one is not allowed even to ask whether a nominee believes things that are not provably true. So you can’t as a senator oppose a nominee because she has the wrong religious convictions, or because she has none and you are religious—or vice versa.

But at another level, our insistence on things like qualifications are meant to bind nominees, at least in their areas of professional competence, to known reality and to professional methodologies. We don’t run federal agencies using Ouija boards, for example. And if the head of NASA were to declare that he would consult astrological charts before launching space missions, a senator—at least up until now, anyway—would tend to regard such a statement as reflecting lunacy, not religious commitment.

And lunacy is a proper basis to oppose a nominee—or, at least, it used to be.

The idea of entrusting the FBI, an institution devoted to the rigorous assembly of actual evidence in order to solve crimes and protect national security, to a man who peddles “Two Thousand Mules” to children comes perilously close to putting an astrologer in charge of NASA.

So does putting a woman in charge of the intelligence community who rejects the craft of intelligence in favor of soundbites from RT on a repeated basis.

And putting someone who doesn’t believe in vaccines in charge of the federal government’s medical research and public health policy is even worse—more akin to putting a flat-Earther in charge of NASA.

It shouldn’t take great courage for senators to determine that such people are simply playing a different game from the games their agencies are playing.

Yet it does, actually, take great courage—which is why so few Republican senators are doing it. I remain hopeful that the three Republican senators who voted against Hegseth can each be persuaded that the rejection of known truths within one’s supposed field—or the embrace of known falsehoods within it—is dangerous and disqualifying as to Patel, Gabbard, and Kennedy.

Where the fourth vote might come from, however, is a bit of a puzzle. And that’s scary. Because voting for these three nominees, each in different ways, is validating delusion—a proposition for which there should not be a Senate majority. Even with the vice president available to break a tie.

The Situation continues tomorrow.