The Situation: How to Get Away With Violating Court Orders

.jpeg?sfvrsn=f6228483_6)

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The Situation on Monday mourned the loss of the Voice of America.

Today, some useful advice for those readers who want to violate court orders.

There seem to be a lot of people out there these days who want to violate court orders—and more still who are keen for others to do so. But let’s be frank. Some people are just better at stiffing federal courts than others are. Some people end up in jail when they defy the courts or refuse to testify before Congress. Some people, by contrast, get to keep running the federal government and get cheeky tweets from foreign heads of state. What’s the difference? It all comes down to technique.

Here are seven rules to follow if you want to defy the courts and get away with it—the dos and don’ts of telling a federal judge to put it where the moon don’t shine.

Rule #1: Never Admit You’re Violating a Court Order

In our turbo-masculinized culture, it may seem like a flex to stand up in court and say, “Your honor, contempt does not begin to describe my feelings towards this court.” Don’t do it—unless you want to go to jail in the short term and have a speaking gig at the Republican convention when you get out.

Instead, always announce you are, of course, complying with the court’s order.

Note the present tense here. If you have not complied so far, saying that you are complying or are committed to complying may not technically be false. You may have already gotten what you need out of defying the order (deporting someone, for example) and are now prepared, after it’s too late, to comply. You may have arguments, however frivolous, that your defiance constitutes a form of compliance (see Rule #3). The point is that the moment you admit you’re violating the order, the court is going to have you for lunch. So keep the judge arguing and confused. And who knows? If enough people post on Twitter that you should defy the judge, maybe he or she will back down and accept your argument as a way of avoiding confrontation.

Rule #2: Accidents Happen and Can Be Great Excuses for Violating Court Orders

Whether it’s accidentally breaking a government payment system or accidentally just not finding out in time that a judge has forbidden a deportation without 48 hours of notice to the court, accidents are often the best excuses for defiance. “Oh, I’m sorry, your honor. The problem was just that your order didn’t make it to the senior official in time to turn around that airplane,” sounds so much better than “We got your order, your honor, and the relevant senior official took it into the bathroom and wiped his ass with it.”

The former will give rise to fact-finding that will take a while and buy time. Maybe the case will settle. Maybe tempers will cool. Maybe it will turn out that the deported person is a baddy after all and nobody will care that you deported her.

Rule #3: You Get to Interpret the Order

The judge gets to issue the order, but remember, in the first instance, you get to interpret the order. And that means that if a judge orders you to do X, and you interpret X to mean Y, then you get to do Y until that judge says that X does not equal Y. And before that happens, you’re going to get to argue about whether X does, in fact, equal Y. And you’ll probably get the chance before being held in contempt to comply with the judge’s own interpretation of X—or even to convince her that while X might not equal Y, it certainly equals Z.

Remember Rule #1 here. You’re always complying with X. It’s just that you interpreted X to mean Y and, when the judge rejected that view, assumed that Z would constitute full compliance.

Rule #4: Always Appeal

A judge cannot punish you for appealing. So appeal. Always appeal. When in doubt, appeal again. And when there’s no basis for an appeal, use the words “emergency appeal” or “mandamus.”

This slows things down. Sometimes, you get a good appeals panel that can really mess things up. And appeals can be a great way to communicate rhetoric about the judge that your political proxies can then take up on Twitter. A single dissenting appeals court judge or Supreme Court justice can turn a perfectly reasonable district judge into a monster. So go for it. You have nothing whatsoever to lose.

The chief justice yesterday even invited this approach, declaring that instead of going after federal judges, the administration should try appeals: “For more than two centuries, it has been established that impeachment is not an appropriate response to disagreement concerning a judicial decision. The normal appellate review process exists for that purpose.”

He’s half right.

¿Por qué no los dos?

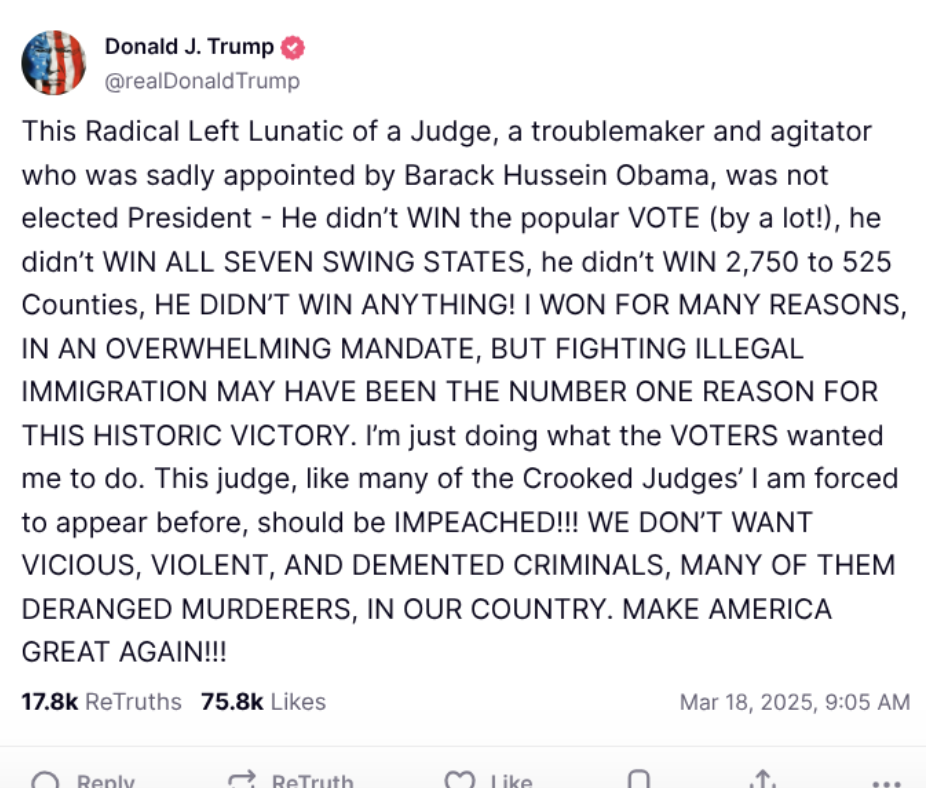

Rule #5: Go After the Judge

Defying an order by a reasonable judge is a bad thing to do, and people won’t appreciate it. So logically, you need to make the judge into an unreasonable person for whom defiance is the only reasonable approach. Here’s how it’s done:

The coolest version of this trick is when you go after the judge in filings to the judge himself, preferably while following Rule #1 and denying that you’re disobeying an order and Rule #3 of advancing—to the judge—a tendentious reading of his own order. “What began as a dispute between litigants over the President’s authority to protect the national security and manage the foreign relations of the United States pursuant to both a longstanding Congressional authorization and the President’s core constitutional authorities has devolved into a picayune dispute over the micromanagement of immaterial factfinding,” the government wrote the other day to the judge for whose impeachment the president was also calling. “Continuing to beat a dead horse solely for the sake of prying from the Government legally immaterial facts and wholly within a sphere of core functions of the Executive Branch is both purposeless and frustrating to the consideration of the actual legal issues at stake in this case.”

Rule #6: Keep Your Lawyers Barefoot and Ignorant

It’s very simple. Don’t give your lawyers enough for them to betray you to the judges.

Remember, they are officers of the court, and while they represent you, they have obligations to the courts. If they don’t know things, they can’t answer judges’ questions. If you don’t tell them who the administrator of DOGE is, they can’t tell your secrets. If they don’t know who has access to government payment systems, the courts can’t issue orders to those people to pay contractors and grantees. An informed lawyer can represent you better but may not be such a great ally for purposes of abject defiance. An ignorant lawyer, by contrast, will do a lousy job of protecting your interests but is a great person to stick in front of a judge to flail away in response to questions about what exactly you’re up to.

Rule #7: Always Make Sure They’re Relieved You Didn’t Do Worse

Judges don’t like it when you disobey their orders. They really don’t like it when their power in general to issue orders and have people follow them gets challenged. So if you’re planning a minor or temporary violation of a court order, make sure to threaten (always out of court, of course) pervasive violations. If you’re planning general compliance with orders with some pushing and testing of the lines here and there, make sure your minions are demanding that you ignore the courts altogether and break federal judges on the rack. This way, the courts will be less outraged at what you actually did than relieved by the restraint you showed in not doing more.

The key overarching point here is that effective defiance of the courts is a subtle art, and it’s not done best with chest-thumping Jacksonian bravado about John Marshall enforcing his orders. It’s done best through plausible deniability, interpretive twists, and tactical ignorance by the people who actually have to appear in front of the judges. It’s about obscuring accountability for compliance. And it’s about making judges so fear catastrophic collapse of their authority that they might find relief in mere erosion.

The Situation continues tomorrow.