The TikTok Law and the Foreign Influence Boogeyman

TikTok’s curation algorithms can drive us crazy only in the ways we want to be crazy.

.jpg?sfvrsn=d49aa3bf_6)

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

We recently got our first glimpse of the government’s approach to defending the TikTok law that Congress passed last session. The Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act prohibits app stores and internet service providers from allowing TikTok (and any other applications from foreign-owned businesses the president’s office may add in the future) to be distributed within the United States unless the foreign state divests and relinquishes control. ByteDance, the Chinese company that owns TikTok, brought a constitutional challenge in TikTok v. Merrick Garland, and the Justice Department recently filed the public version of its reply brief. As expected, the government is leading with the argument that Chinese control over TikTok creates national security threats based on data collection and foreign propaganda.

I am going to largely sidestep the data collection issue. While Congress might have a freer hand, constitutionally speaking, to ensure that passively created data generated in the U.S. (and about Americans) is not transferred to China, the law seems to suffer from serious under-inclusion. After all, any tech company with assets in China could be pressed through Chinese law to divulge information about Chinese dissidents around the world. Hence the long-standing debate about whether any responsible tech company should conduct business in China.

This piece focuses on the threat that TikTok’s curation choices give China an unacceptable level of influence over the thoughts, beliefs, and political actions of Americans. The government refers to this threat as “covert content manipulation,” so I will use that phrase, too, even though it uses rhetoric to stack the deck. Here is how the Justice Department characterizes the threat:

[T]he application employs a proprietary algorithm, based in China, to determine which videos are delivered to users. That algorithm can be manually manipulated, and its location in China would permit the Chinese government to covertly control the algorithm—and thus secretly shape the content that American users receive—for its own malign purposes.

I agree with every word of that paragraph. Moreover, I would even stipulate that the Chinese government is trying to exploit its control over TikTok for some purpose that serves Chinese interests that are against our own. Nevertheless, there is a difference between intent and impact.

The threat posed by these efforts is mostly illusory. Propaganda does not work unless listeners want it to work. American listeners have minds of their own, and those minds are stubborn. Falsehoods, divisive content, and moral panics proliferate on TikTok (as they do on any social media platform), but the users who are willing to believe and interact with that content must already be motivated to believe it. Beliefs cannot be spun from thin air by a social media company. Most of the yarn has to be there already.

Chinese control of TikTok is unlikely to cause any more (or less) harm than other economically successful social media companies. Most of the harms from social media come from its core function: serving content that people want, and helping like-minded people coordinate around half-baked, often wrong ideas.

Have Faith: Propaganda Doesn’t Really Work

The animating concern Congress tried to address in the TikTok ban was the threat of foreign influence operating through content selection and promotion. As Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-Wisc.) explained the impetus for the ban, “[Y]ou’re placing the control of information—like what information America’s youth gets—in the hands of America’s foremost adversary.”

China, Russia, and other foreign adversaries undoubtedly will at various times, including possibly now, attempt to disrupt American political and social order by creating or amplifying social media content that serves their interests. There is credible evidence, for example, that the TikTok algorithm differs from the newsfeed algorithms of other social media platforms by systematically over- or under-representing certain forms of content depending on its bearing on Chinese politics. The government’s brief adds further evidence of China’s effort to shape content delivery:

TikTok and ByteDance “employees regularly engage” in a practice called “heating,” in which certain videos are manually promoted to “achieve a certain number of video views.” ... TikTok does not disclose which posts are “heated,” and public reporting found that China-based employees had “abused heating privileges,” with the potential to dramatically affect how certain content is viewed.

Thus, Chinese employees and perhaps members of the Chinese government itself can hand-select content for boosting (the more common and less incendiary term for “heating”) or shadow-banning much the way we know that Meta, Twitter (X), and other American social media companies routinely do. But to what effect? The government seems to rely on the “injection” theory of persuasion, as if social media users can be tricked into believing things that don’t already conform to their world view or beliefs, and that are destructive to themselves or to society. By the government’s implicit logic, exposure to content works like a virus that enters the eye and infects the brain.

But we know something from the experience of American social media firms: They don’t have a lot of rope to play with. They can’t make more than marginal changes to beliefs and behaviors unless users are already motivated toward the cause. If curation algorithms fail to give users the content the users want most (which is, sadly, content that is more inflammatory and that confirms what they already believe), the users go away.

Unless there is something in the heavily redacted portions of the government response, the government has offered no evidence, and no reason to assume, that these “heating” efforts have any meaningful impact on the actual beliefs and political conduct of Americans. Thus, contrary to Alan Rozenshtein’s excellent summary of the constitutional analysis, in which he argued that the threat of foreign manipulation was well justified, I think the national security threats are highly speculative.

The feared power of Chinese influence is mostly contradicted by social media experiments that test how content moderation and “push” messaging affects listener beliefs. When put to the test, efforts to sway people into a belief or into an act that they otherwise wouldn’t take are failures. This is because people tend to trust and engage with content that reflects what they already believe. They are surprisingly hard to persuade out of their preexisting beliefs, and the process of persuasion is still mysterious. Not even the largest platforms or voice pieces have the power to control culture or debate through sheer access to eyes and ears.

There are too many examples to describe all of them (see the appendix for a sense of what is out there), but here are a few important ones:

The Reverse Chronological Order Study

Meta facilitated an experiment where almost 50,000 Facebook and Instagram users were randomly assigned to either their standard content algorithm (control) or a reverse chronological feed (experiment). Those who believe that the curation algorithm is the source of power typically see reverse chronological feeds as an antidote to polarization and manipulation. But other than reducing engagement, the reverse chronological feed (activated for three months) had no measurable effect on polarization.

The Poke to Vote Study

Another Facebook study, referred to as “Poke to Vote,” supposedly showed Facebook has the power to influence who votes and who stays home.

The study compared the voting behavior of 60 million users who saw a social prompt to vote with pictures of friends who voted (like the one shown above) to hundreds of thousands of users who either saw the same message without the names and pictures of friends or no prompt at all. The headlines suggested that Facebook has the power to sway elections, but the actual effect was underwhelming: Voter turnout for those who saw the social prompt was 0.4 percent higher than it was for the group who saw no message. And crucially, the only content driving this small effect was the information about friends. Facebook’s use of the purely informational poke to vote—the one that didn’t include information about friends who voted—had no detectable influence on voting behavior whatsoever (as compared to the users who saw no prompt to vote at all). So the small amount of influence Facebook has to play with is dependent on what the content actually says. The influence was mediated through the user’s real-life social groups (hey, your in-real-life friends voted!) and not the power to control what messages the user saw at the top of their feed.

The Friend Network vs. Exposure vs. Selection Study

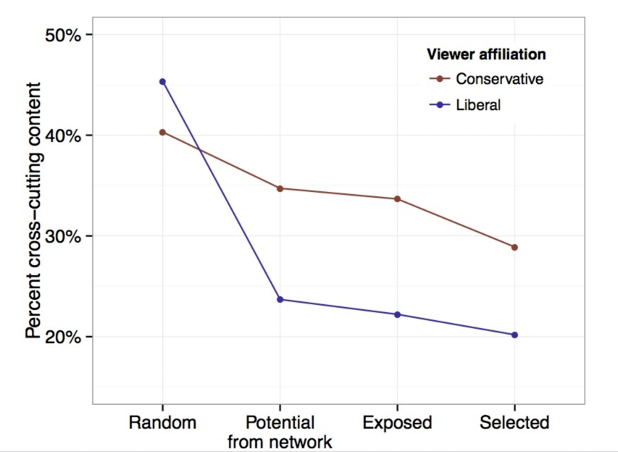

This diagram, from a study published in Science, provides one of the most revelatory pieces of evidence that social media users have minds of their own. This experiment showed that if Facebook users had been given a random selection of possible Facebook content, over 40 percent of the political content they would see would be cross-cutting (that is, generally understood to come from the ideological perspective opposite to the one the Facebook user seems to hold). Much of the filter bubble phenomenon is caused by a social media user’s selection of friends, and this is especially true for liberal Facebook users. The algorithm then further pares down cross-cutting content a bit, but by less than it would if it were optimizing for engagement alone, or the likelihood of being clicked.

In other words, Facebook’s algorithm actually attempts to stifle, to some extent, tribalism and political segregation, but its users press forward with it anyway. It is not easy to nudge humans into confronting ideas and evidence that don’t come from their own team.

Over All, We Are Stubborn

A recent article published in Nature comprehensively surveyed the research on how social media affects the spread of misinformation and extremist content. The authors “document a pattern of low exposure to false and inflammatory content that is concentrated among a narrow fringe with strong motivations to seek out such information.”

When distressing social media content goes “viral,” it is tempting for lawmakers and public intellectuals to blame platform algorithms for injecting disfavored viewpoints into the minds of users. But the causal relationship mostly runs the other direction: Organic, preexisting social or political phenomena cause an uptick in social media content.

Even if an inorganic, brute-force imposition of content onto users did have some impact on changing beliefs, the short-term gains from that manipulation would be a liability for the social media company in the long run. Pushing content that users don’t want causes users to spend less time on the platform or abandon it altogether. After all, as the government itself acknowledges, “The backbone of TikTok’s appeal is its proprietary content recommendation algorithm.” The government emphasizes the risk from the algorithm being “proprietary,” but to have any lasting influence it also needs to have “appeal.” Remember the study of Facebook and Instagram users that applied a reverse chronological algorithm for three months, forcing users to see content that was not optimized for their interest and engagement? In it, researchers found that users in the chronological feed group spent “dramatically less time on Facebook and Instagram.”

The differences in liking and commenting behavior were also dramatic:

As Colin Jackson once put it, “Information Is Not a Weapons System.” It is marketing. American advertising firms, professional persuaders working at the cutting edge of big data techniques for decades, have a difficult time getting consumers to change their purchasing behavior. When it looks like a digital advertising campaign has worked, the “lift” (as they call it in the profession) is half mirage: Much of the time, the clicks that follow a digital ad turn out to come from the people who would have bought the exact same product anyway.

State-run media cannot automatically get consumer appeal, especially when there are multiple other media options. Americans sometimes have the mistaken belief that individuals living under authoritarian regimes believe the propaganda they are forced to endure. But people who lived under such regimes, like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn or Timur Kuran, have explained that the goal of propaganda is rarely to persuade, and more often to dull the spirit and test for conformity to the state message despite disbelief. Without the gulag and persecution of dissidents, propaganda is only as effective as our current beliefs and our social or political tribes let it be.

You Should Have More Cynicism!

I do not mean to give the impression that social media has no impact on society. Of course, social media impacts society and enables all sorts of good and bad things that otherwise would not occur. But these effects are mostly dependent on preexisting beliefs: The most a social media company could do is to enable or throttle conformity and coordination around the things people already tend to believe.

Thus, the biggest weakness in the U.S. First Amendment theory of democratic deliberation is that Americans (like all humans) have too much attachment to their beliefs, too much tendency to use motivated reasoning, and too much interest in cherry-picked information to confirm what they or their tribe already believe. But to the extent these human flaws can be exploited, our problems are much bigger than China. Domestic political parties, for example, have as much or more reason to exploit motivated reasoning, tribalism, and conformity on social media than foreign actors do. (See, for example, this study finding that messaging from British political parties tended to cause recipients to have less accurate beliefs about the economy and immigration.) Nevertheless, we give this political speech the highest possible level of First Amendment protection, not because American political speakers have good intentions (or even better intentions than foreign speakers, though this may be true), but because the government is not fit to decide which ideas are beyond the pale. However indirect it may be—through forced sale and restriction of American intermediaries—the TikTok law has as its main goal protecting Americans from bad ideas.

Instead the goal should be to find social, economic, and even legal policies that will help Americans consume media with greater critical thinking. If there are ways to reduce Americans’ interest in online content that plays on reactive and tribal instincts, these techniques would bring real progress. They would treat the demand side of the market for falsehoods instead of the supply side. There might be some tools that can do this or that can help aid Americans in the “critical ignoring” of low-quality content. But short of a near-ban on engaging social media platforms regardless of ownership (a “solution” that would be a nonstarter on First Amendment grounds), all we are left with, realistically, is the hard slog of cultivating curiosity, humility, and reason. Perhaps, out of necessity, social media users will eventually rise a little closer to the aspirational First Amendment listener, thoughtfully considering the ideas on offer and doggedly pursuing the truth—but that’s a long way off.

Some Limiting Principles

This assessment about foreign control over social media algorithms could change if the facts change. Three examples that come immediately to mind are just-in-time manipulation, artificial intelligence (AI) hyper-customized manipulation, and corruption of other institutions.

Just-in-Time Manipulation

One could imagine that a large social media platform might be able to cause significant damage through a one-time push of false information. An 11th-hour deepfake about a political candidate could affect an election, for example. If this is the nature of the risk, Congress could have a freer hand. After all, when Justice Louis Brandeis said that the remedy for bad speech is more speech, his caveat was “if there be time.” But Congress likely has no reason to see this as a credible threat because any manipulation of this sort that is broad enough to have a real impact would also be broad enough to detect, and fairly rapidly. It would also mark the end of trust in TikTok and other Chinese companies—a trade-off that China would not likely go for.

AI Hyper-Customized Manipulation

It is also fair to reserve judgment on technologies and strategies that might be available in the near future to show or create the most potent sort of manipulative information for each individual. If a company has enough personal data to create customized, highly deceptive or addictive information, then we may inch closer to the “injection” theory of belief manipulation. But currently, there is little evidence of this.

Corruption of Other Institutions

The reasoning in this piece applies only to speech systems that are voluntarily accessed by Americans. It would not apply to schools, physical products, military contractors, voting machines, or any number of areas where the government has interests related to non-speech conduct. Based on special reasoning in bedrock First Amendment cases, it also wouldn’t apply to electioneering or to broadcast companies (although I have some doubts about the logic of the latter). The arguments here depend on the listeners being in charge of whether a company does well or not. When the listeners aren’t in charge, a different analysis would have to apply.

We’ve Seen This Before: Fear of Propaganda Does Not Override Free Speech

The rush to react to foreign propaganda is a prominent feature in American free speech history. Indeed, the First Amendment rights Americans enjoy today were shaped by a Supreme Court that grew weary of speech restrictions that sprung from moral panics over socialist and communist propaganda.

In the social media era, there is no doubt that the United States’s enemies and frenemies have found a new vessel for their attempted influence and conspiracies, and it’s understandable to worry about this. Courts have had to be responsible stewards of constitutional rights against the temptation to combat propaganda. If Joseph McCarthy was the human embodiment of the fear of surreptitious foreign influence, then the Supreme Court has been the institutional embodiment of patience and skepticism, and for good reason.

Congress has no legitimate interest in protecting Americans from the influence of speech that they have voluntarily engaged with. The threats from TikTok’s “covert manipulation” through a curation algorithm are greatly overstated, and as far as the public can see, the government has not offered a smidge of evidence that TikTok has successfully caused a swing in political beliefs that would not have swung on their own. On balance, foreign propaganda is unlikely to have significant effects on American beliefs and conduct.

Ironically, bills like the TikTok ban and the alarmist rhetoric that propel them are more likely to cause a diminution in trust in American political institutions and to give China a win. After all, the suppression of foreign propaganda reveals that the U.S. government itself believes that the United States’s adversaries are powerful, and that its voters are mindless sheep—an own-goal political message from which hostile foreign adversaries stand to benefit.

Additional Resources

- Sacha Altay et al., “Misinformation on Misinformation: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges,” Social Media & Society 1 (2023).

- Joshua Benton, “Good News: Misinformation Isn’t as Powerful as Feared! Bad News: Neither Is Information,” Nieman Lab, Jan. 10, 2023.

- Sandra Gonzalez-Bailon et al., “Asymmetric Ideological Segregation in Exposure to Political News on Facebook,” 381 Science 392 (2023).

- Andrew M. Guess et al., “How Do Social Media Feed Algorithms Affect Attitudes and Behavior in an Election Campaign?” 381 Science 398 (2023).

- Peter Kafka, “Are We Too Worried About Misinformation?” Vox, Jan. 16, 2023.

- Brendan Nyhan et al., “Like-Minded Sources on Facebook Are Prevalent but Not Polarizing,” 620 Nature 137 (2023).

- Hugo Mercier & S. Altay, “Do Cultural Misbeliefs Cause Costly Behavior?” in The Cognitive Science of Beliefs (J. Musolino et al., eds., 2022).

- Cody Butain et al., “YouTube Recommendations and Effects on Sharing Across Online Social Platforms,” 5 Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interactions 11(1) (2021) (similar finding for YouTube videos).

- Zeve Sanderson et al., “Twitter Flagged Donald Trump’s Tweets With Election Misinformation: They Continued to Spread Both On and Off the Platform,” 2 Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 1 (2021) (finding that tweets removed on Twitter were much more likely to be shared on other platforms than tweets that were not removed, suggesting that users use substitutes to access and share their preferred content).

- Andrew Duffy et al., “Too Good to Be True, Too Good Not to Share: The Social Utility of Fake News,” Information, Communication & Society (2020).

- Andrew M. Guess et al., “‘Fake News’ May Have Limited Effects Beyond Increasing Beliefs in False Claims,” 1 Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review (2020).

- Hugo Mercier, Not Born Yesterday: The Science of Who We Trust and What We Believe (2020).

- Kevin Munger et al., “The (Null) Effects of Clickbait Headlines on Polarization, Trust, and Learning,” 84 Public Opinion Quarterly 49 (2020).

- Brendan Nyhan, “Facts and Myths About Misperceptions,” 34 Journal of Economic Perspectives 220 (2020).

- J.W. Kim & E. Kim, “Identifying the Effect of Political Rumor Diffusion Using Variations in Survey Timing,” 14 Quarterly Journal of Political Science 293 (2019) (finding that the diffusion of the rumor that Barack Obama is Muslim caused an increase in that belief, but did not cause any change in attitude toward Obama).

- Pablo Barbera et al., “Who Leads? Who Follows? Measuring Issue Attention and Agenda Setting by Legislators and the Mass Public Using Social Media Data,” 113 American Political Science Review 883 (2019).

- In a study that spanned the period when false information was spreading about President Obama being a Muslim, researchers found that there were more people who believed that Obama was Muslim after the diffusion of the rumor. But the increase was almost entirely driven by the subset of individuals who already disliked Obama, and the rumor had no measurable effect on whether they would vote for him. J. W. Kim & E. Kim, “Identifying the Effect of Political Rumor Diffusion Using Variations in Survey Timing,” 14 Quarterly Journal of Political Science 293 (2019).

- J.L. Kalla & D.E. Broockman, “The Minimal Persuasive Effects of Campaign Contact in General Elections: Evidence From 49 Field Experiments,” 112 American Political Science Review 148 (2018).

- Melanie Langer et al., “Digital Dissent: An Analysis of the Motivational Contents of Tweets From an Occupy Wall Street Demonstration,” Motivation Science (2018).

- Noortje Marres, “Why We Can’t Have Our Facts Back,” Engaging Science, Technology, and Society, July 24, 2018.

- Kevin Munger, “Tweetment Effects on the Tweeted: Experimentally Reducing Racist Harassment,” 39 Political Behavior 629 (2017).