The Trump FCC’s Coercion Cartel

The Trump FCC is not protecting free speech—it’s undermining it.

The first few weeks of the second Trump administration have combined the “shock and awe” of the 2003 invasion of Iraq with the Silicon Valley mantra “move fast and break things.” The shock treatment—Elon Musk’s ascendency, Jan. 6 pardons, a Gaza Riviera, the Ukraine retreat, and so on—distracted attention from how President Trump and agencies of government such as the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) are moving fast to break three foundational principles of American government and democracy: fair and legitimate investigations, judicial review, and executive branch agency independence.

Culture War-Themed Investigations

The effort begins with FCC Chairman Brendan Carr’s initiation of culture war-themed investigations based on the application of undefined or ill-defined regulatory concepts, the details of which are known only to him. Such actions recall Justice Antonin Scalia’s admonition, in a 2015 Supreme Court decision, that “[t]he vagueness of the law can invite arbitrary power.” In this case, Carr’s message is clear to those the FCC regulates: “Fall in line or this could be you.”

The same day that then-President-elect Trump named Carr to be chairman of the FCC, the incoming chairman identified his priorities by posting on X:

Carr’s framing of “censorship” incorrectly conflates the true meaning of the term—the involvement of the state in matters of speech that are protected by the First Amendment—with a politicized version created to attack the exercise of those First Amendment rights in editorial decisions.

Such manipulation of a foundational concept fits directly within the culture war claims advanced by President Trump and Elon Musk that conservative voices are systematically silenced. Independent research does not support these claims. Notably, it is apparently not “censorship” when Elon Musk, owner of X, removes content from the platform based on personal preference.

Nevertheless, dismantling the “censorship cartel” at the FCC appears to involve the creation of a “coercion cartel” to achieve submission.

The Trump FCC is working at warp speed to disrupt long-standing norms and rapidly intimidate those it regulates to adopt its agenda before resistance can build.

In the administration’s first weeks, Carr unilaterally launched investigations relating to or affecting the editorial decisions of media outlets. Such investigations are likely to have a chilling effect on free speech decision-making of the targets while also serving as a warning to others that they could be targeted as well.

For example, reopening a complaint previously dismissed by the agency in January, Chairman Carr inserted the FCC into candidate Trump’s claim that CBS’s editing of a “60 Minutes” interview with Kamala Harris constituted “election interference.” Prior to the election, candidate Trump sued CBS over the matter. After assuming office, the president posted on Truth Social, “CBS should lose its license”—which is a decision that falls within the FCC’s jurisdiction.

Carr linked the allegations against CBS to the pending sale of Paramount Global and its CBS subsidiary, a transaction that requires FCC permission to transfer the broadcast licenses. “I’m pretty confident that that news distortion complaint over the ‘60 Minutes’ transcript is something that is likely to arise in the context of the FCC review of that transaction,” the chairman not-so-subtly warned on Fox News.

At a time when a congressional Republican is calling public broadcasting “communist” and holding hearings on its content, the FCC has targeted public broadcast networks PBS and NPR. “I am writing to inform you that I have asked the FCC’s Enforcement Bureau to open an investigation regarding the airing of NPR and PBS programming across your broadcast member stations,” Carr wrote to the network presidents. The local member stations, he charged, “could be violating federal law … [by] broadcasting underwriting announcements that cross the line to prohibited commercial advertisements.” Expressing the hope that “this investigation may prove relevant to an ongoing legislative debate … whether to stop requiring taxpayers to subsidize NPR and PBS programming,” he added, “for my own part, I do not see a reason why Congress should continue sending taxpayer dollars to NPR and PBS.”

This threat to the funding of public broadcasting, of course, jeopardizes the content those outlets provide. Ironically, it was a Republican-led effort in 1981 that restructured the funding of public broadcasting, reducing direct government support while allowing limited underwriting messages as a financial offset.

Another use of the chairman’s investigatory powers is Carr’s inquiry into the reporting practices of the San Francisco radio station KCBS. The station reported on specific details of an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raid of office buildings in the city, including the location of the raid and descriptions of ICE vehicles. Speaking on “Fox & Friends,” the chairman justified the investigation on the grounds of determining how KCBS’s reporting “could possibly be consistent with their public interest obligations.”

The FCC’s recent investigations and inquiries reveal a broader strategy to leverage the agency’s regulatory power to affect what the public hears by influencing what media outlets say. Framing editorial discretion as “censorship” and deploying government authority, the Trump FCC is not protecting free speech. It is undermining a practice essential to American democracy.

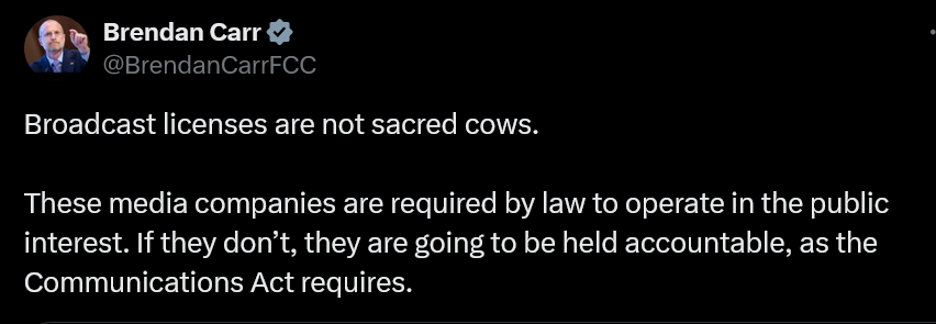

Further, in a pointed warning that his agency controls broadcasters’ licenses—and will be monitoring their behavior—the chairman stated:

That broadcasters “are going to be held accountable” for their editorial decisions is the ultimate breaking of the free speech guarantees that have provided stability for years. At the heart of this threat is the chairman’s interpretation of a core concept of the FCC’s authority: the “public interest.” Public interest is an inherently ambiguous term, therefore inviting a fluid application that shifts depending on the decision-maker. The Trump FCC’s interpretation of the vagaries of the standard to scrutinize the editing of a videotape, the underwriting of a public broadcaster, or the news coverage of an ICE raid illustrates the vast discretionary powers of the FCC chairman to exploit the imprecision of the public interest standard for political purposes.

At a time when the U.S. Supreme Court has constrained the ability of federal agencies to interpret their statutes—implementing the major questions doctrine requiring statutory specificity and eliminating court deference to the expertise of specialized agencies—Chairman Carr has exploited the vagaries of the public interest standard to weaponize it as a coercive tool. To his credit, he has suggested starting a rulemaking process to define the parameters of the public interest standard. This is an important proposal, as the use of ill-defined government policy as a tool of political coercion is historically associated with authoritarian governments.

However, whether such a rulemaking will ever materialize is doubtful. To deliver on his proposal, the chairman would need to craft a standard that simultaneously preserves editorial discretion for those whose messaging aligns with the Trump administration while enabling coercion of those whose messaging does not.

Avoiding Judicial Review

One of the protective foundations of FCC procedure has always been the right to appeal an agency action to a court. Virtually every major agency decision is appealed. In such a review, the court determines whether the agency acted within its statutory authority, decided based on the facts in the record and not in an arbitrary and capricious manner.

Chairman Carr’s recent actions, however, appear designed to evade judicial review. The recent actions are taken on the authority of the chairman and without a decision of the commission itself. As a result, there is no final decision that can be appealed for court review. Unlike cases such as the Supreme Court’s review of the dismantling of the United States Agency for International Development (and undoubtedly others to come), Carr’s actions are not reviewable until—and unless—they ever become final agency decisions.

Presumably, the drafters of the Communications Act envisioned that the FCC’s other commissioners would serve as a check on an overreaching chairman. But the chairman has the ability to unilaterally interpret the hazy term “public interest” and therefore direct the agency’s resources—which accordingly puts a powerful, nonreviewable tool in the hands of a single individual.

Should the commission eventually make a final decision on any of the ongoing matters, that decision could be appealed. In the interim, however, one person’s decision to deploy the FCC’s sizable investigative powers has a significant and intimidating effect on all those the agency regulates.

Carr has unilaterally extended the use of coercive investigations. In November 2024, before he assumed the role of chairman, Carr sent a letter to the CEOs of Alphabet (Google), Meta, Microsoft, and Apple declaring that each individual had “participated in a censorship cartel” that “is an affront to Americans’ constitutional freedoms and must be completely dismantled.” He also warned the CEOs that “once the ongoing transition is complete, the Administration and Congress will take broad ranging actions to restore the First Amendment rights that the Constitution grants to all Americans—and those actions can include both a review of your companies’ activities as well as efforts by third-party organizations and groups that have acted to curtail those rights.” Once the presidential transition was complete, Carr initiated an investigation.

The FCC has never before asserted regulatory authority over these online platforms. Yet Carr now appears intent on claiming such jurisdiction by invoking a 1996 statute originally designed to protect online editorial freedom that happened to be placed in the Communications Act—Section 230.

Navigating Section 230 presents another threading-the-needle challenge for the chairman. Section 230(c)(1) protects platforms such as Meta and X from liability when they choose not to engage in content moderation—an approach seemingly favored by the Trump team. Section 230(c)(2) also protects the companies from liability when they do engage in editorial decisions, but that protection is more limited, as it applies only to actions taken “in good faith to restrict access to or the availability of a material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious.”

As the author of the Project 2025 chapter on the FCC, then-Commissioner Carr outlined his strategy: “The FCC’s Section 230 reforms should track the positions outlined in a July 2020 Petition for Rulemaking filed at the FCC near the end of the Trump Administration. Any new presidential Administration should consider filing a similar or new petition.” The proposal referenced was an executive order at the end of Trump’s first term directing the secretary of commerce to petition the FCC to rule on whether a platform’s editorial decisions were made in “good faith.”

If he intends to “break things” further, Carr might want to attempt an even broader interpretation of Section 230. He hinted at this possibility in his Project 2025 chapter: “The FCC should issue an order that interprets Section 230 in a way that eliminates the expansive, non-textual immunities that courts have read into the statute. As one of the FCC’s previous General Counsels noted, the FCC has authority to take this action because Section 230 is codified in the Communications Act.”

This assertion is questionable—especially in light of the aforementioned recent Supreme Court decisions that limit agency discretion. The mere fact that a provision is included in the Communications Act does not inherently grant the FCC authority to interpret and enforce it. Yet, once again, such an expansion of the FCC’s authority can also be achieved based on the chairman’s discretion, without a formal decision by the commission, thus avoiding judicial review of whether the law permits such an action.

All the chairman needs to do is instruct his general counsel to issue a policy statement—like former FCC Chairman Ajit Pai did during the first Trump administration—asserting the FCC’s authority to interpret Section 230. Even without making a binding ruling, the chilling effect is likely to be immediate. Ultimately, platforms may appeal subsequent actions, but in the interim the chairman will have at least temporarily harnessed the FCC’s coercive capabilities to further a political agenda.

Additionally, the FCC’s expansive new policies extend well beyond issues of content. When President Trump issued an executive order entitled “Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing,” the chairman quickly fell in line. Shortly after Trump’s order, Carr wrote a letter urging the CEO of the Comcast Corporation to eliminate any diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) practices, in which he revealed that “[a]t my direction the FCC has already taken action to end its own promotion of DEI.”

Ending equal opportunity initiatives at the FCC represents a tragic disregard for the lives of the agency’s workforce, whose daily activities, both large and small, sustain the commission’s operations. For example, I have seen the opportunities the FCC has provided for individuals with disabilities and the positive impact resulting from the promotion of egalitarian opportunity. Thanks to the chairman’s decision, however, many FCC employees now fear for their future.

Another Trump executive order, “Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity,” attempted to export this approach to the private sector. However, because executive orders are typically used to direct government action rather than dictate private-sector practices, Section 4 of this order speaks only of “Encouraging the Private Sector” to abandon DEI activities.

In a letter to Comcast announcing an FCC investigation into its human resource practices, the chairman goes beyond the “encouraging” language of the executive order. Citing an alleged “violation of FCC regulations and civil rights laws,” the letter pointed to Comcast’s website, which declared equal opportunity as “a core value of our business.” The FCC then ordered Comcast to “provide the FCC’s Enforcement Bureau with an accounting of Comcast’s and NBCUniversal’s DEI initiatives, preferences, mandates, policies, programs, and activities,” effectively inserting the commission into the private company’s human resource management.

The letter also contains an explicit warning to all other FCC-regulated companies: “[T]he FCC will be taking fresh action to ensure that every entity the FCC regulates complies with the civil rights protections enshrined in the Communications Act … including by shutting down any programs that promote invidious forms of DEI discrimination.” This statement is particularly ironic given that multiple sections of the Communications Act—Section 257, regarding elimination of entry barriers for women and minorities; Section 309(j), regarding the auction of spectrum licenses; Section 151, the general Purposes of the Act; Section 334, on equal employment opportunity in broadcasting; and so on—direct the FCC to promote diversity in both ownership and employment across the industry.

It is worthy of note that the FCC did not take similar action against Fox Corporation and Fox News—which have traditionally provided positive coverage of Trump—despite that company’s 2023 Proxy Statement boasting how it “[p]romoted inclusion and diversity through our approach to talent recruitment, development and retention.”

“Every single business that’s regulated by the FCC,” Carr told the New York Post, “have now got the message that the time to end their invidious forms of DEI discrimination is now.” That message, however, was delivered absent any official act by the commission—a threat with no appeal.

Attacks on Executive Branch Agencies’ Independence

The third assault on foundational principles involves the use of presidential executive orders and a Justice Department ruling to strip agencies such as the FCC of their independence, put them under White House supervision, and threaten any commissioners who might disagree with the Trump agenda.

Collectively, these measures further expand the coercion powers of the FCC and its chairman. The first of these executive orders, issued on Feb. 18, was entitled “Ensuring Accountability for All Agencies.” The order eviscerates the independence of agencies explicitly chartered by Congress to operate outside of the executive branch. More specifically, under this directive, all previously independent agencies must obtain White House approval for “all proposed and final regulatory actions.”

The Republican-controlled Senate Committee on Homeland Security detailed the importance of independent agencies in a 2016 report. The report states, “The Federal Communications Commission (FCC or Commission) is an independent federal agency … [d]eriving its regulatory authority from Congress … [and] intended to ensure the agency is free of partisan political pressure, and independent of the policy aims of the Executive Branch.” Titled, “How the White House Bowled Over FCC Independence,” this report is of particular significance to me because I was its target when I was FCC chairman.

Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.), then-chairman of the committee, initiated the report. Like most Republicans, he opposed the decision the FCC made regarding “net neutrality”—specifically, the determination that internet service providers were common carriers under the law. The legislators charged that President Obama exerted inappropriate input into the commission’s decision. Over the course of nine days, five different Republican-controlled congressional committees grilled me, alleging inappropriate White House interference. Ultimately, the FCC inspector general—who opened an investigation on instructions from Congress—found no wrongdoing.

Strikingly, many of those same elected officials who decried presidential influence over independent agencies have now endorsed President Trump’s executive order erasing that independence. Sen. Johnson, for instance, told reporters the order placing the president in control of the decisions of the FCC was “completely appropriate.”

If the order is allowed to stand, the president will have preapproval of all proposals before they are even considered by the commission, and final approval of decisions once they are made. It will make a charade of the Administrative Procedure Act’s guarantee of public input to the decision-making process and the requirement that the agency’s decision not be made capriciously but rather based on the facts in the record.

After eliminating the independence of regulatory agencies, President Trump expanded the power of his appointees leading those agencies. A Feb. 19 executive order, “Ensuring Lawful Governance and Implementation of the President’s ‘Department of Government Efficiency’ Deregulatory Initiative,” instructs agency heads “to determine whether ongoing enforcement of any regulations in their regulatory review is compliant with law and Administration policy … [and] then direct the termination of all such enforcement proceedings that do not comply with the Constitution, laws, or Administration policy.”

The order further dismantles independent agencies such as the FCC by empowering the agency heads—in this case the FCC chairman—to bypass the usual vote among commissioners to cease enforcement of duly enacted regulations disfavored by the Trump administration. Such unilateral action, of course, would follow the instructions of the previous executive order to clear everything with the White House.

The coup-de-grâce of this administrative trifecta is the Department of Justice decision that the president has the authority to remove the commissioners of independent agencies at will. In a letter to Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), ranking member of the Judiciary Committee, Acting Solicitor General Sarah M. Harris advised, “the Department of Justice has determined that certain for-cause removal provisions that apply to members of multi-member regulatory commissions are unconstitutional.” In other words, terminations without cause are allowed based on a presidential whim.

President Trump’s removal of the Democratic commissioners on the Federal Trade Commission establishes that this is not an idle threat. These positions (like those of the FCC) were statutorily created and the commissioners confirmed by the Senate for a fixed term. Nevertheless, President Trump has overturned precedent to give himself a de facto Sword of Damocles over each commissioner. Chairman Carr has enthusiastically joined this threat, telling an interviewer, “The Communications Act … does not include for-cause removal protection of FCC Commissioners because in 1934, Congress didn’t think it could constitutionally restrict the president’s authority to remove a commissioner.”

Beyond the coercive “vote with me or lose your job” pressure, dismissing commissioners who dissent from the Trump agenda has the added political advantage of silencing conflicting voices. Once removed, these seats—and their independent voices—would remain vacant indefinitely as the president controls nominations and could simply decline to make new appointments.

***

These actions are being carried out by the people’s government, allegedly in the name of the people.

At the FCC, they mark an unprecedented expansion of government intrusion into free speech and a direct assault on those engaged in promoting equal opportunity.

At the macro governmental level, they undermine the constitutional balance of power by bypassing co-equal branches of government to enlarge presidential authority through self-serving presidential decree.

The founding fathers designed the American government as a bulwark against the abuse of power. The practices of President Trump and the Trump FCC—circumventing established legal processes, consolidating power, and coercing independent decision-makers—constitute an assault on those principles.

.jpg?sfvrsn=407c2736_6)