Thoughts on the Mar-a-Lago Search and the President’s Classification and Declassification Authority

Here’s why the defense asserted by Trump's team—that while in office Trump issued “standing orders” that any “documents removed from the Oval Office and taken to the residence were deemed to be declassified the moment he removed them”—is nothing short of absurd and laughable.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Charlie Savage's piece "Presidential Power to Declassify Information, Explained," published yesterday in the New York Times, is an excellent and informative writing on the classification authority and how it might impact a potential criminal case against former President Donald Trump for wrongful possession at Mar-a-Lago of documents containing classified and highly sensitive information.

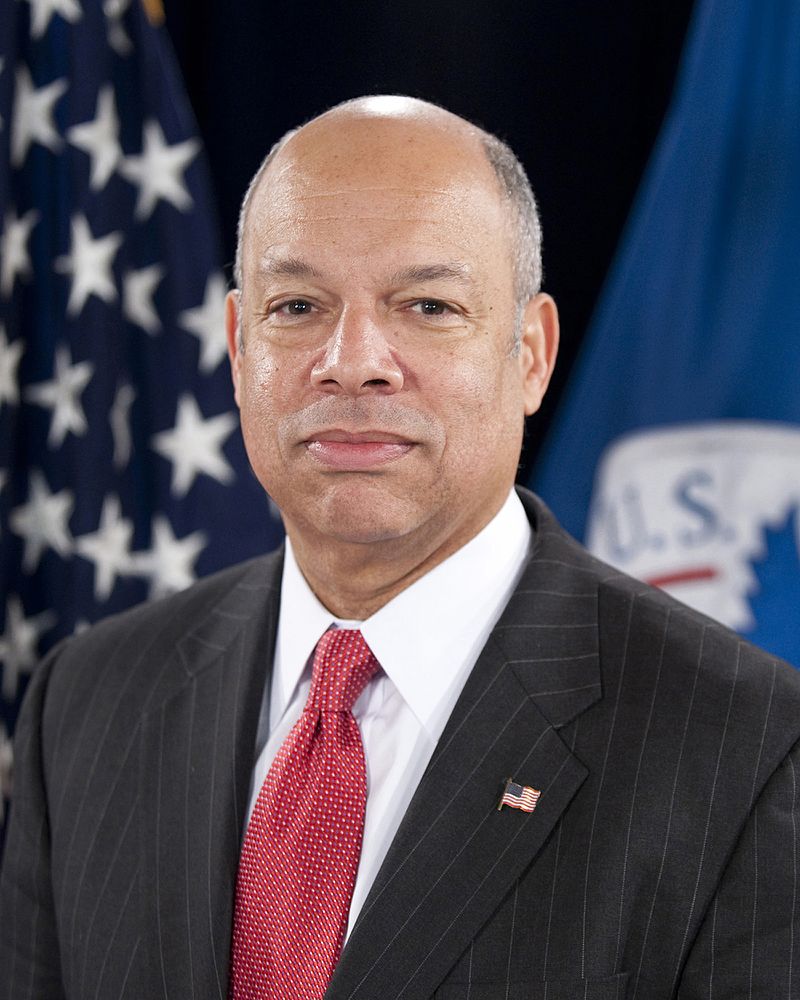

As someone who for a time handled, read, created and relied upon classified documents on a daily basis, I offer these additional thoughts:

First, it is important to note that documents themselves are not classified; it is the substance of the information contained therein that is classified. A single document may contain classified and unclassified information, such that it could be released to the public or press in response to a Freedom of Information Act request with redactions of the classified information. This happens all the time. Indeed, the standard practice for the creation of any classified document is to mark the beginning of each paragraph with "(U)", "(S)" or "(TS)"—indicating whether the information in the particular paragraph is unclassified, or classified at the Secret or Top-Secret level.

Second, Charlie is correct that the classification and declassification of government documents, and the system created to accomplish that, is derived from the President's authority as commander-in-chief, not from a law passed by Congress. Thus, by definition, the executive authority that creates this system of classification, and all the processes and bureaucracy arising from it, can be overridden by the executive at any moment. (Here it is worth noting, as Charlie does, that there are criminal laws that forbid the concealment of sensitive government documents, regardless of whether and how they are classified.)

A very legitimate example of an exercise of the president's declassification authority is this: suppose the president is about to have a bilateral meeting with another head of state somewhere, and wants to share classified information with that president in the best interests of the United States and its relationship with that other nation’s government. Many classified documents bear the express marking "NOFORN"—i.e., it may not be shared with any foreign national. Undoubtably, a U.S. president has the authority to make a unilateral and summary decision to share that information with his or her foreign counterpart without following the normal and very cumbersome process for declassifying documents or information—though doing so may be deeply unwise without first consulting all the relevant national security agencies to understand the implications of revealing that classified information to another government.

Third, part and parcel of any act of declassification is communicating that act to all others who possess the same information, across all federal agencies. This point holds true regardless of whether the information exists in a document, an email, a power point presentation, and even in a government official's mental awareness. Otherwise, what would be the point of a legitimate declassification?

In light of all this, the defense asserted by Trump's team—that while in office Trump issued "standing orders" that any "documents removed from the Oval Office and taken to the residence were deemed to be declassified the moment he removed them"—is nothing short of laughable. It's a little like saying that the speed limit on the New Jersey Turnpike is whatever speed the governor chooses to drive at in any given moment.

Should there be a criminal case against Trump for the removal and possession of sensitive government information at his personal residence, his defense will present the nation and the courts with another example of a president who for four years was willing to push traditional and responsible uses of executive authority to absurd levels—the very definition of abuse of power.

As Jack Goldsmith noted in another context for Lawfare in 2017, in the first year of the Trump presidency, "[t]he current conundrum highlights again how very deeply our system of government depends on the People electing a President who is generally reasonable, prudent, and responsible."

In 2016 the American people engaged in a dangerous experiment: electing to the powerful office of the presidency a man with virtually no public office experience, no understanding of the Constitution or history, no respect for law, no moral compass, possessed only of autocratic impulses and a thirst for power for the sake of power. With the violent events of Jan. 6, 2021 and each new facet of the many investigations surrounding Trump, we continue to pay the price for that experiment.

In my opinion, whether our democracy recovers fully from this experiment remains an open question.