Throwback Thursday: The Lieber Code

Introduction

“The law of war is of fundamental importance to the Armed Forces of the United States.”

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Introduction

“The law of war is of fundamental importance to the Armed Forces of the United States.”

So begins the recently published, long awaited Department of Defense Law of War Manual. Given that the manual is over a thousand pages long, there’s certainly plenty to debate—but this Throwback Thursday looks to contextualize the conversation around long-running threads of U.S. military ethics, focusing on one particular detail: the manual’s relationship to the Lieber Code and the principle of distinction.

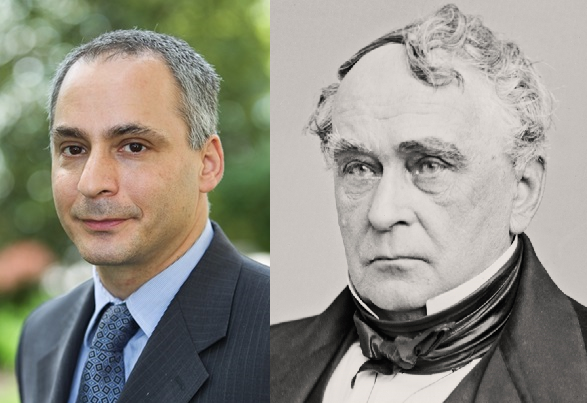

The Law of War Manual begins by citing the Lieber Code, the Civil War-era code of military conduct drafted by Francis Lieber and issued as General Order 100 to the armed forces by President Lincoln in April 1863. While the Lieber Code’s effectiveness in governing military behavior during the Civil War continues to be the subject of debate, it’s generally agreed to have been influential in subsequent attempts to draft rules for wartime conduct—rules that have been promulgated to armed forces around the world. Indeed, Lieber’s code of military ethics is often credited as the first systematic attempt to codify the laws of war—both within the United States and internationally—and the 2015 manual necessarily follows in its tradition.

The Law of War Manual’s repeated references to the Lieber Code demonstrate the continuity in the evolution of military ethics over the last 150 years. This, despite modern warfare’s gradual blurring of the lines between civilian and combatant: thanks first to twentieth-century total warfare, in which entire populations were mobilized and targeted alongside the military; and second, to twentieth- and twenty-first-century asymmetric conflicts incorporating terrorism and guerrilla warfare. More recently, targeted killings and drone strikes have forced the United States to deal with these questions anew, particularly in cases like that of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula cleric Ibrahim al Rubaysh. Yet the articles of the Lieber Code show that this issue, and others, are as old as efforts to codify the laws of war—efforts, in other words, to give the lie to General Sherman’s famous statement that “war is cruelty and you cannot refine it.”

The echoes of Lieber’s thinking ring loudly in the new DOD Law of War Manual.

“Farmers by day, fighters by night”

One of the Lieber Code’s most crucial provisions is Article 22, which declares the importance of “the distinction between the private individual belonging to a hostile country and the hostile country itself.” That is to say, Article 22 puts forward “the principle…. that the unarmed citizen is to be spared in person, property, and honor as much as the exigencies of war will admit.”

Lieber’s reference to the distinction between civilians and “men at arms” is instructive. The principle of distinction is a foundational tenet of just war theory and international humanitarian law: civilians must be distinguished from combatants, and attacks may not be directed against them. This doesn’t, of course, mean that no civilians may ever be killed, only that soldiers may not intentionally target them independent of a proportional attack on a military target. Notably, the Law of War Manual cites Article 22 as a paradigmatic and “longstanding explanation… of the principle of distinction.”

Yet the principle of distinction is often more easily explained than executed.

Alongside its endorsement of distinction as the manifestation of “civilization[‘s]... advance[ment] during the last centuries,” the Lieber Code includes some interesting provisions that foreshadow the DOD manual’s approach to civilian participation in hostilities. In Article 155, the Code once more stresses the distinction between the “general classes” of “combatants and noncombatants,” but then distinguishes between loyal and disloyal civilians “in the revolted part of the country.” Article 156 goes on to say that,

Common justice and plain expediency require that the military commander protect the manifestly loyal citizens, in revolted territories, against the hardships of the war as much as the common misfortune of all war admits… The commander will throw the burden of the war, as much as lies within his power, on the disloyal citizens, of the revolted portion or province, subjecting them to a stricter police than the noncombatant enemies have to suffer in regular war.

If the commander sees fit, Lieber writes, “he” may administer a loyalty oath and “expel, transfer, imprison, or fine” all those civilians who refuse to take the oath.

These provisions are instructive, as they recognize a difference between civilians who do and do not affiliate themselves with enemy forces. Article 156’s statement that “common justice” requires loyal citizens to be protected from wartime bears a notable similarity to the principle of distinction more generally, but the provision then goes on to advocate treating disloyal civilians more harshly—seemingly aligning them with the enemy, if not going so far as to declare them legitimate targets of military action.

Today, the Lieber Code’s distinction between loyal and disloyal citizens appears strange, either a relic of an earlier era or a signpost of a road not taken in the laws of war. The contemporary law of war determines the status of civilians not on the basis of loyalty or disloyalty, but on their activities in the field of combat. There are clear cases where civilians are entitled to protection under the laws of war, whether they are supportive of their country’s cause or not. The trouble arises in the more ambiguous cases—that is, situations in which civilians move beyond simply supporting their troops and begin to look suspiciously like combatants.

In that vein, the new DOD manual goes on to note the difficulties of applying the principle of distinction in practice as well as theory. “An implicit consequence of creating the classes of lawful combatants and peaceful civilians,” it suggests, is the necessity of acknowledging those cases in which the two classes begin to blur or overlap.

As readers well know, the Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions address these concerns through a concept called “direct participation in hostilities,” or DPH. Civilians in the act of “DPH-ing” are permissible targets for military action. They can be attacked and shot just as any soldier can---with the crucial distinction that soldiers may be targeted whether or not they’re engaging in a combat operation, whereas a DPH-ing civilian can be targeted only “for such time” as they directly participate. The DOD manual uses the language of direct participation in hostilities as well, despite its emphasis that this usage does not indicate U.S. adoption of the Additional Protocols’ standards for DPH. (The U.S. has not ratified the Additional Protocols but accepts certain provisions as customary international law.)

Generally speaking, the manual seems to accept a similar standard as that set forward in the Protocols: insofar as civilians directly participate in hostilities, they are “unlawful combatants” no longer protected according to the principle of distinction. They may be the subject of military attack, and, if captured, will not be awarded the protections due to prisoners of war.

The Lieber Code also discusses unlawful combatants, especially those fighters that might seek to shield themselves from attack through “the semblance of peaceful pursuits.”

Article 82 is particularly telling:

Men, or squads of men, who commit hostilities, whether by fighting, or inroads for destruction or plunder, or by raids of any kind, without commission, without being part and portion of the organized hostile army, and without sharing continuously in the war, but who do so with intermitting returns to their homes and avocations, or with the occasional assumption of the semblance of peaceful pursuits, divesting themselves of the character or appearance of soldiers - such men, or squads of men, are not public enemies, and, therefore, if captured, are not entitled to the privileges of prisoners of war, but shall be treated summarily as highway robbers or pirates.

The first point of interest here is the Code’s provision that these civilians who act like combatants should be treated as criminals, rather than soldiers. The DOD manual implicitly draws on this Article in its designation of “private persons who engage in hostilities” as unlawful combatants.

Second, Lieber here acknowledges that this type of unlawful participation in hostilities need not be constant, but is often interspersed with “returns to the… home”—as in the case of the proverbial “farmer by day and fighter by night,” who cycles between his various occupations. Today’s DOD manual describes this as the “revolving door” phenomenon. If the standard requires that a civilian lose protection while directly participating in hostilities and regain it while conducting peaceful pursuits, our imagined farmer will lose and gain protection from direct attack depending on whether he happens to be holding his sword or his ploughshare.

The Israeli Supreme Court grappled with this question in the Targeted Killings case, stating that a civilian who joins a terrorist organization and commits a “chain of hostilities, with short periods of rest between them” is not protected from attack during those rest periods: rather, “the rest between hostilities is nothing other than preparation for the next hostility.” This position represents a rejection of the “revolving door” and an expansive view of the Additional Protocols’ “for such time” clause. (Note that Israel accepts Additional Protocol I as customary international law.) Strikingly, Section 5.9.4 of the DOD manual not only cites the Targeted Killings case on this matter but essentially paraphrases its reasoning. The manual emphatically rejects the revolving door, saying that the adoption of such a rule would “risk diminishing the protection of the civilian population.”

Bill Boothby has suggested—in an article cited by the DOD manual—that Article 82’s reference to “intermitting returns” indicates both Lieber’s awareness of the revolving door problem and his rejection of the on-again, off-again protection that the revolving door might offer. And indeed Lieber can be read to understand the “returns to the home” as nothing more than breaks in a continuing “chain” of hostilities. On this view, fighters like William Quantrill’s Raiders made only “intermitting” or “occasional” returns to their homes, engaging in “the semblance of peaceful pursuits” rather than the pursuits themselves. Perhaps Lieber was concerned with forestalling what might have been an early incidence of lawfare—“bushwhackers” attempting to shield themselves from attack through involvement in civilian life, then riding out to attack Union soldiers at the next bridgehead.

The DOD manual again draws on the Targeted Killings case on the matter of what direct participation in hostilities entails, citing the case to argue that “planning, authorizing or implementing a combat operation,” is sufficient to render a person targetable. According to the manual, this is true even if the individual in question does not personally conduct the operation on the ground. As in the case of the time window during which an individual is targetable, this represents a broad view of what constitutes direct participation.

In comparison to the activities that the Lieber Code considers sufficient to strip away the protections of civilian status, how does the DOD manual’s reading measure up? Article 82 designates “fighting,” “raiding,” and “plundering” as activities that render the perpetrator a criminal, consistent with the modern designation of unlawful combatancy that follows from direct participation in hostilities. The Code also declares that “war-traitors” (civilians who pass information to the enemy) and “war-rebels” (civilian inhabitants of occupied territory who “rise in arms” against the occupying forces) may be killed. (Though it’s somewhat ambiguous whether “war-traitors” may be the target of attack, or whether they may only be executed as punishment---the Code states that they should “suffer death,” but makes no mention of military trial or other procedure.)

Raiding, fighting, and spying all fit comfortably and uncontroversially under the umbrella of participation in hostilities. Crucially, however, the Code also states that “war-rebels” can be denied prisoner of war status—consistent with treatment of unlawful combatants—even if “discovered and secured before their conspiracy has matured to an actual rising or armed violence.” That is, Lieber treats as-yet-unsuccessful plotters as having a comparable status to those actually carrying out violence.

There is a notable similarity here to the DOD manual’s statement that “planning… a combat operation” constitutes direct participation in hostilities. Both the Code and the DOD manual treat civilian conspirators who have not carried out any acts of violence as unlawful combatants, expanding the notion of direct participation to include the planning of an attack in addition to the act of attacking itself. On the other hand, the DOD manual arguably takes a broader view of direct participation: the Code’s provision concerns plotters who will carry out attacks in the future, whereas the DOD manual widens its scope to include commanders or advisors who dispatch others to carry out attacks for them and may never themselves participate in an act of violence.

Interestingly, Lieber’s approach represents something close to the modern criminal charge of conspiracy to commit terrorism, though he conflates criminal conspiracy with unlawful combatancy under the laws of war. In this instance, perhaps the Code can be read as foreshadowing post-9/11 debates over the confused interaction of warfighting and law enforcement.

Conclusion

The DOD manual’s relatively broad view of both the time period during which a civilian directly participating in hostilities may permissibly be the subject of attack, and of the activities that render one subject to attack, flow (if not perfectly) from the manual’s distant origins in the Lieber Code. Read closely, the Code seems to contemplate and address the case of the “farmer by day and fighter by night,” and suggests a view of participation that includes the planning stages before violence itself.

The Law of War Manual’s treatments of the principle of distinction and civilian participation in hostilities can claim a pedigree stretching back to the beginning of the American laws of war—even those aspects of the manual that seem most contemporary.