Tort Law and Frontier AI Governance

The development and deployment of highly capable, general-purpose frontier AI systems—such as GPT-4, Gemini, Llama 3, Claude 3, and beyond—will likely produce major societal benefits across many fields. As these systems grow more powerful, however, they are also likely to pose serious risks to public welfare, individual rights, and national security. Fortunately, frontier AI companies can take precautionary measures to mitigate these risks, such as conducting evaluations for dangerous capabilities and installing safeguards against misuse. Several companies have started to employ such measures, and industry best practices for safety are emerging.

It would be unwise, however, to rely entirely on industry and corporate self-regulation to promote the safety and security of frontier AI systems. Some frontier AI companies might employ insufficiently rigorous precautions, or refrain from taking significant safety measures altogether. Other companies might fail to invest the time and resources necessary to keep their safety practices up to date with the rapid pace at which AI capabilities are advancing. Given competitive pressures, moreover, the irresponsible practices of one frontier AI company might have a contagion effect, weakening other companies’ incentives to proceed responsibly as well.

The legal system thus has an important role to play in ensuring that frontier AI companies take reasonable care when developing and deploying highly powerful AI systems. Ex ante regulatory governance is one obvious strategy the law might employ. Legislatures and administrative agencies could enact safety standards that frontier AI companies must meet; officials could then monitor whether these companies are in compliance and bring enforcement actions when they are not. Regulatory governance might also involve the creation of a “licensing regime” under which companies must proactively seek permission from regulators before engaging in certain activities, such as developing or deploying AI systems that are especially likely to pose serious national security risks.

Ex ante regulation of AI is controversial, however, and effective regulatory regimes are not always easy to design. It is not clear whether or when an adequate U.S. regulatory regime for frontier AI will be established, especially since doing so will likely require federal legislative action. So it is worth exploring other legal mechanisms that might mitigate the safety and security risks posed by frontier AI.

In this article we explore one such mechanism: the tort system, which empowers people who have been harmed by negligent or dangerous activities to sue for compensation and redress in civil courts. In general, the specter of adverse tort judgments or costly settlements can incentivize companies to adopt more effective safety practices, thereby reducing the risk that their activities or products might cause serious harm to consumers and third parties. In this way, tort law can productively influence the behavior of frontier AI developers. Tort liability is thus one mechanism, among others, for incentivizing AI companies to adopt responsible practices.

We suggest that tort law has an important, albeit subsidiary, role to play. For several reasons, which we discuss below, tort law’s ability to effectively govern frontier AI risk (and safety risk more generally) is limited. If forced to decide between administrative regulation and tort law as an instrument of frontier AI governance, we should probably choose the former. Still, until meaningful administrative regulation is instituted, tort law could help to fill the gap in frontier AI governance—especially if it is suitably modified by state or federal legislation. And even after robust regulation is enacted, tort law might play a valuable auxiliary role in governing the risks of frontier AI development.

In the rest of this piece, we provide more detail on tort law, how it might apply to frontier AI developers, and how it might be modified by statute to better govern frontier AI development and deployment. Our focus is on the handful of companies (such as OpenAI, Anthropic, Google DeepMind, and Meta) engaged in developing and deploying highly powerful frontier AI systems. To be sure, tort law might also play a salutary role in governing other entities involved in the frontier AI value chain—such as users, fine-tuners, providers of tools for AI agents, internet intermediaries, cloud compute providers, and chip manufacturers—but we leave the discussion of this to future work. Throughout, we focus on U.S. tort law—or, to be more precise, the closely related bodies of tort law found in the 50 U.S. states. Many of our points will be applicable, however, to other common law jurisdictions (such as the U.K. and Canada), and some may be applicable to civil law jurisdictions (such as Germany and France) as well.

Tort Law Already Applies to Frontier AI Developers

In common law systems, tort law is principally made by judges in the course of adjudicating cases. The principles of tort law are thus found mostly in court decisions, rather than legislative or regulatory enactments. That said, lawmakers can modify tort law, in general or as it applies to certain activities, by passing suitable legislation. And regulatory rules and industry standards can powerfully influence courts’ decisions about tort liability.

Compared to other bodies of law, tort law is perhaps most notable for its breadth of coverage: It governs a vast range of risky activities, by default, because it imposes on everyone a general duty to take reasonable care in order to avoid causing harm to other people’s persons or property (alongside more limited duties in respect of other forms of injury, such as reputational and emotional harm). While this general duty can in certain cases be limited by contract, it is not derived from contract; a company or person owes this duty to everyone foreseeably put at risk by its activities. Frontier AI developers thus already have considerable liability exposure under existing tort law: If their systems cause physical harm or property damage, and they have acted negligently in developing, storing, or releasing these systems, they may be liable to pay damages to injured parties.

In applying this negligence standard, courts take into account a range of considerations and sources of guidance, including legal precedent and expert scientific opinion. If the defendant has violated a statute designed to protect victims against the sort of harm that it caused, the court will often treat this fact as powerful or even conclusive evidence that the defendant behaved negligently. Similarly, courts generally treat failure to comply with safety-oriented industry standards, customs, and best practices as strongly probative of negligence.

If the developer’s action is subject only to the negligence standard, then it will be held liable for harming the plaintiff only if it has failed to take reasonable care. In certain cases, however, AI developers may also be subject to strict liability—that is, they may have to pay for harms they have caused even if they took all due care to avoid causing those harms.

There are multiple forms of strict liability recognized by the law. One form of strict liability applies to certain abnormally dangerous activities, such as keeping wild animals or storing explosives in populated areas. In determining whether an activity qualifies as abnormally dangerous, courts consider factors such as the magnitude of the risks it poses, the extent to which those risks can be reduced through reasonable care, the extent to which the activity is socially valuable on balance, and whether the activity is common or unusual in the community. Since developing and releasing frontier AI systems is an activity undertaken only by a small number of firms, which might end up posing unusually large risks of harm—if, say, AI systems become capable of autonomously carrying out cyberattacks—it could conceivably qualify as abnormally dangerous, and therefore subject to strict liability. But courts are generally quite hesitant to expand the list of activities deemed abnormally dangerous. Moreover, courts typically decline to impose strict liability on manufacturers for dangerous objects once those objects have been sold (or otherwise left their control and possession).

Frontier AI developers might also be subject to specialized products liability doctrines, if AI systems are classified as “products” by the courts. (There is still scant case law on whether software systems are products for the purpose of products liability law, but the most common answer appears to be no, except where software is incorporated into a physical product.) Products liability law is sometimes described as “strict.” It is more accurately characterized, however, as a mix of different liability standards, some of which are more strict in character and some of which are more negligence-like. The extent to which products liability doctrines are strict, rather than (or in addition to) negligence-like, varies considerably from state to state. Although the specialized contours of products liability doctrine might have considerable bearing on AI developer liability disputes, we will omit any sustained discussion of them in what follows. It is worth observing, however, that the strict or semi-strict character of products liability doctrine in many states is a significant additional source of liability risk for AI developers, given the live possibility that at least some states’ courts will classify AI systems as “products.”

Whatever the precise liability standards to which frontier AI development will be subject, frontier AI developers are well-advised to take substantial precautions to ensure that the systems they develop and deploy are safe. A developer that takes such precautions will not only reduce the risk that its systems will inflict injuries on other people; it will also reduce its liability exposure in the case that its systems do inflict such injuries, for it will reduce the risk that a court will find that its injurious activities failed to exhibit reasonable care.

By way of concrete illustration, consider the following three potential cases:

- Careless development. A company develops a powerful general-purpose AI model. In the course of assessing the model’s capabilities, the researchers prompt it to create a sophisticated computer worm. The worm exploits a vulnerability in the company’s containment measures and escapes the test environment. It eventually spreads to millions of machines worldwide and causes significant property damage. The company may thus be liable for failing to take reasonable precautions to guard against the risks of enhancing the model’s capabilities.

- Autonomous misbehavior. A company develops and releases a powerful general-purpose AI model. Some months later, a user instructs it to achieve a seemingly innocuous goal (for instance, making money). The model pursues this goal in an objectionable manner—for instance, by hacking into bank accounts—that is neither intended nor predicted by its user or developer (although this possibility was, at least arguably, foreseeable to the developer). The company may thus be liable for failing to take reasonable precautions to guard against the risk that the model might dangerously malfunction upon release.

- Intentional misuse. A company develops a powerful general-purpose AI system. The company decides to release this system without carefully evaluating its potential for misuse or equipping it with reasonably effective safeguards against such misuse. Within months, a bad actor uses the system to develop a sophisticated computer worm that causes millions of dollars of property damage. The bad actor would not have been able to develop or utilize this computer worm if they had not enjoyed access to the AI system, or if it had been equipped with reasonably effective safeguards against such misuse.

In all of these cases, it is plausible that the developer is liable under existing tort law for the injuries it has caused by failing to exercise due care in development and deployment.

That said, AI developer liability under existing tort law is unclear in important respects. There is some case law on tort liability for the manufacturers of certain specialized AI devices, but there is little if any on the liability of companies developing general-purpose frontier AI models. It remains to be seen how courts will formulate the frontier AI developer’s duty of care, adjudicate whether a developer has breached this duty, and elaborate the application of other important tort doctrines in the distinctive technical context of frontier AI development.

It is not clear, for example, how courts will determine whether a victim’s injuries are “unforeseeable” (which typically precludes tort liability for such injuries). Nor is it clear under what circumstances courts will hold an AI developer liable for negligently enabling a bad actor to cause harm with the developer’s model, such as by failing to equip the model with reasonably effective safeguards against its misuse.

The modern trend is to treat third-party misuse as an “intervening cause” that precludes liability if this misuse was unforeseeable to the defendant. The fact that many AI experts in industry and academia are warning of the possibility of serious forms of misuse, and the fact that many frontier AI companies acknowledge this possibility, will tend to support the conclusion that such forms of misuse are foreseeable. It is plausible, then, that many courts will entertain suits against frontier AI developers for failing to take reasonable measures against at least some forms of misuse of their systems—just as courts have recently entertained suits against other product manufacturers for failing to install reasonably effective safeguards against the misuse of their systems or products. If a court entertains such a suit against a frontier AI developer, it will be for the jury to decide whether the developer took adequate care against the instance of third-party misuse at issue.

But other courts might not entertain such suits. In practice, “foreseeability” is a somewhat nebulous and pliable concept. Courts may sometimes deem a plaintiff’s injury “unforeseeable” because it seems unfair or otherwise undesirable to hold the defendant liable for it. In other cases, courts have explicitly shielded product manufacturers (such as gun manufacturers) from liability for enabling the foreseeable misuse of their products, partly on the basis that opening the door to such liability would be socially undesirable or present administrative difficulties for the judicial system.

Thus different states could take significantly different approaches to developer liability for third-party misuse of AI, just as different states have taken significantly different approaches to determining the liability of gun manufacturers for mass shootings. More generally, the fact that each state has its own body of tort law may give rise to considerable heterogeneity in how the U.S. tort system treats frontier AI developer liability.

Why Tort Law?

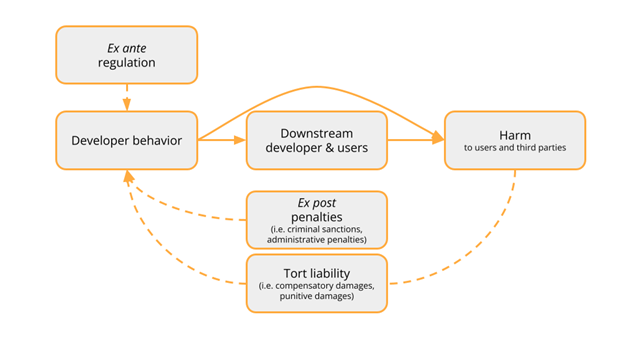

Figure 1. Harm-reducing behavior on the part of developers can be incentivized in roughly three different ways. First, ex ante regulation can mandate that companies comply with certain safety practices. Second, should they fail to comply, they can be sanctioned via ex post penalties, such as fines from regulators, or criminal sanctions in egregious cases. Third, should harm occur, developers can be required by courts to pay compensatory or punitive damages if they are found liable.

Even if tort law applies to frontier AI developers, why should we think it is an appropriate instrument of frontier AI governance? Why not rely on regulation alone? An obvious answer is that, for the time being at least, there is little if any regulation of frontier AI development in the United States. Until robust regulatory requirements are instituted, tort liability might be able to serve as an important stopgap in preventing irresponsible AI development from causing severe harms, and redressing such harms if they occur.

And even if a robust regulatory regime is enacted, there are good reasons for it to be supplemented with tort liability. After all, administrative regulation is itself an imperfect and limited instrument of risk governance. So while legislatures are entitled to decide that compliance with regulatory requirements should insulate a developer from tort liability, we believe they should proceed carefully before making any such decision.

For one thing, there are important respects in which tort liability tends to be more adaptable than regulation, which may be especially valuable in rapidly evolving technological domains. Sometimes innovation proceeds with sufficient rapidity that regulatory decision-making fails to keep pace. Rather than requiring a regulator to proactively update requirements to keep up with the technology before harms can materialize, a tort regime allows decision-makers to consider each case on its merits and make fine-grained determinations about adequate care after harm has occurred. This may be especially important given the significant asymmetries in information and technical competence that will likely exist between regulators and the frontier AI companies they are tasked with regulating.

Tort liability may also be less vulnerable to industry capture than regulation. The possibility that regulators will be unduly influenced by the companies they are regulating can dilute the efficacy of regulatory enforcement or weaken the incentive effects of regulatory sanctions. Since tort cases will be adjudicated by a multitude of courts, ranging across different states, they may be a less vulnerable target for lobbying and influence than a centralized government agency. To be sure, the tort system is not immune to such problems. Frontier AI companies may be well-resourced enough to influence tort law across multiple courts and jurisdictions. And since tort liability is determined in part by statutory requirements and safety regulations, there is scope for industry influence via traditional channels: Industry and interest groups have long played a role in U.S. “tort reform” efforts. Still, the tort system provides an important additional bulwark against the distortions that industry capture might work upon the legal system’s governance of safety risk.

In addition, tort liability can strengthen developers’ incentives to comply with safety regulations, since courts will treat the failure to adhere to these rules as powerful evidence of negligence. The prospect of paying damages to injured victims, in addition to applicable regulatory penalties to the government, increases the expected cost of noncompliance. This may be especially valuable in contexts where compliance with regulatory requirements is difficult for regulators to detect or verify.

Finally, tort law can encourage developers to invest in safety beyond the requirements set by regulation. Strict liability would provide especially clear incentives to do so, since developers could be held liable for harms even if they adhere fully to regulation. However, negligence liability can also incentivize companies to act more safely than required by regulation. For instance, if a company fails to comply with industry safety standards—which are widely followed by industry participants, though not required by regulation—this fact will often lead a court to decide that the company has failed to take reasonable care. Unless a legislature has specified otherwise, courts typically treat compliance with applicable regulatory requirements as necessary, but not sufficient, for a company to avoid liability.

Limitations of Tort Liability

Despite these attractive features, tort liability also has a number of limitations as a means of governing frontier AI development and deployment. Some of these limitations might be substantially ameliorated by legislative modification, but others are likely to persist. These limitations suggest that, while tort liability is a desirable complement to ex ante regulation, it cannot serve as an adequate substitute for it.=

For one thing, tort law requires an injured plaintiff to demonstrate the right sort of causal chain between the defendant’s action and the injury she has suffered. This may be challenging in the case of frontier AI development, given the difficulty of establishing a link between the actions of a developer, the behavior of a model, and a particular harm. If an AI system enables a bad actor to steal a victim’s bank login credentials, she may never become aware that AI (let alone the particular system in question) was involved. Additional issues will arise from the involvement of multiple actors in the AI value chain (including developers, fine-tuners, internet intermediaries, and downstream users).

Tort law also has limitations when it comes to addressing very large harms from AI, such as major catastrophes causing thousands of deaths. Judges sometimes find ways to limit a company’s liability for large-scale harms, on the basis that “enormous” or “indeterminate” liability is unfair or socially undesirable. Even when liability is imposed for large harms, the compensation that can be extracted from a company is limited by its financial resources. So tort law cannot financially incentivize a company to take proper care to avoid harms so large that the resultant damages would exceed the company’s capitalization. Supplementing tort liability with ex ante regulatory requirements is an obvious way to address this problem.

Moreover, the tort system is not well-equipped to deal with certain societal harms from AI—for instance, negative effects on the information environment, or election interference—which do not translate straightforwardly into concrete physical injuries or property damage. And if harms from AI systems are spread among many victims, or across multiple jurisdictions, this may pose practical obstacles to litigation. For these reasons, even a perfectly calibrated tort liability regime will significantly under-deter wrongful or socially undesirable behavior. Regulatory requirements are again a promising tool for addressing this limitation, since they can, for example, compel developers to take precautions against the danger that their models will enable election interference.

The development of tort doctrine might also move too slowly to provide well-calibrated incentives for frontier AI development. Absent legislative intervention, the pace at which tort law develops is determined by the frequency of relevant cases reaching court. And there can be significant lag time—often several years or even decades—between the filing of a tort claim and a final judgment. Moreover, the generation of new tort law through judicial decision is bottlenecked by the fact that the vast majority of viable tort claims are settled before judgment. There are powerful incentives for plaintiffs and defendants to dispose of claims by settlement rather than letting the onerous and expensive litigation process take its course. (That said, the sclerotic character of the litigation process can enhance safety incentives, as well: The threat of protracted litigation and settlement can powerfully shape company behavior.)

Another potential problem is that, since tort liability’s incentive effects rely on the rational judgment and risk perception of potential defendants, the tort system could foster winner’s curse-like dynamics, under which the companies that most enthusiastically develop and deploy models are the companies that judge their models the safest—however irrationally—rather than the companies whose models are properly judged the safest. The prospect of this perverse phenomenon is a strong reason to supplement tort liability with regulatory requirements that obligate all companies developing sufficiently powerful models to take certain important precautions, whatever their own assessment of the attendant risks may be.

Tort liability, especially strict liability, could also unduly hinder socially desirable innovation. While liability is an important tool for internalizing negative externalities, activities like AI development will also produce significant positive externalities. A liability regime could hurt societal welfare by disincentivizing AI developers from engaging in forms of behavior that externalize greater expected benefit than expected harm. Strict liability runs a greater danger of having this effect than negligence liability. As discussed above, however, strict liability also has important benefits. Thus the optimal mix of negligence liability and strict liability rules, in governing AI development, warrants further study.

Lastly, assessing whether an AI developer has exercised reasonable care, or even whether an injury derives from an AI system, may often be a highly technical matter. It is arguable that judges and juries lack sufficient technical expertise to competently make such judgments. Courts can address such concerns, of course, by relying on existing industry standards and expert testimony. But the availability and reliability of these mechanisms might be limited, in this context, by the close professional and social connections that exist between the companies developing frontier AI systems and (many of) the field’s leading technical researchers.

These considerations suggest that tort liability is not an adequate substitute for regulation but rather, at most, an appropriate complement. Tort liability and regulation can be mutually reinforcing. The specter of liability provides additional incentive to adhere to or exceed regulatory standards, while these standards help to establish clear baselines for “reasonable care” in tort litigation.

It might be argued, however, that subjecting AI development to both tort liability and administrative regulation would unduly burden innovation. The fact that tort law accords considerable (albeit not dispositive) significance to regulatory compliance helps to address this concern: If and when a robust regulatory regime is put in place, a developer will be able to argue that it wasn’t negligent by pointing to its compliance with relevant regulatory requirements. By default, however, regulatory compliance is simply evidence of reasonable care, not a safe harbor from liability. There is an argument that regulatory compliance should instead serve as a complete or partial defense to AI developers’ liability, in order to avoid unduly hampering innovation. Similar debates are a mainstay in legal scholarship about the interaction of regulation and liability in other risky domains.

Modifying AI Developer Liability by Legislative and Regulatory Intervention

Some of the foregoing limitations of the tort system can be addressed, to a substantial extent, by legislative intervention. While the common law is largely developed by courts, state and federal legislatures can modify or displace it by statute. For example, the 1957 Price-Anderson Act, and subsequent amendments, established the liability and mandatory insurance regime for civilian nuclear power in the United States.

State and federal legislatures could reduce legal uncertainty, and provide more effective incentives for responsible AI development, by passing appropriate legislation—for example, by clarifying or modifying the application of tort doctrines about foreseeability and enabling misuse to AI development. Legislation could also clarify or modify rules on burdens of proof, rules apportioning damages between developers and other entities in the AI value chain, rules governing supra-compensatory damages for harms caused through especially risky or reckless behavior, and other tort doctrines that will play a central role in shaping the incentives of AI developers. Of particular importance, perhaps, legislation could help to clarify the forms of precaution that reasonable care requires on the part of frontier AI companies.

Legislative intervention could also address the danger that existing tort law will create perverse incentives for AI companies. Negligence liability may lead companies to minimize their liability exposure, rather than minimizing the actual risk of harm. For example, fear of liability exposure could disincentivize companies from adequately investigating or documenting the risks their models might pose, for fear that creating such a record might later help plaintiffs establish negligence. Legislatures could address this risk by requiring that companies investigate and document these risks, specifying that doing so will constitute evidence that developers were not negligent, or replacing negligence liability with strict liability for certain kinds of risk.

Regulatory agencies could shape developer liability by establishing regulatory requirements that companies must fulfill in order to discharge their duties of reasonable care in developing, storing, and releasing models. And they could create, or encourage the creation of, industry standards, customs, and best practices that will inform courts in determining whether developers have exhibited reasonable care.

In these ways, well-tailored legislative and regulatory modifications might substantially increase tort law’s efficacy as an instrument of frontier AI governance. (By the same token, of course, poorly designed intervention might worsen the existing legal regime.) At the time of writing, there are active discussions about AI liability at the U.S. federal and state levels. More work is needed to better understand how existing tort law will be applied to frontier AI development and to explore what changes and clarifications to the liability regime could encourage responsible practices.

Avenues for Future Research

Researchers and policy practitioners could contribute to this work in several ways:

- Investigating the duties of care that should govern frontier AI developers in negligence cases. Well-designed statutes could enhance incentives for proper precaution by imposing specific and precisely articulated duties of care. Scholars, lawyers, and policy practitioners might fruitfully explore what these duties should look like. Possibilities include duties to evaluate models for risks of misuse and autonomous misbehavior; duties to implement reasonably effective safeguards to reduce these risks; and duties to adequately discuss and deliberate about these risks when making major decisions about developing, storing, and releasing highly powerful models (or providing them with access to important societal infrastructure). It is also plausible that developers should have duties to secure the weights of sufficiently high-risk models, in order to prevent these models from being stolen by bad actors or geopolitical adversaries.

- Exploring whether it would be desirable to subject AI developers to strict liability in certain situations. Strict liability may be especially valuable in cases where courts are likely to find the negligence determination difficult, where evidence of negligence may be difficult to produce, or where a negligence liability regime would produce perverse incentives (for example, incentivizing developers not to collect evidence of risks).

- Exploring the relationship between tort doctrine and liability insurance in frontier AI development. Tort law can also enhance incentives for safety by shaping the terms on which companies are able to obtain liability insurance. Companies in many industries regularly purchase liability insurance to protect themselves against liability exposure. Insurers often serve as private quasi-regulators and could plausibly be expected to incentivize AI companies to behave responsibly by charging them higher rates if they fail to adopt risk-reducing practices. It is currently unclear—on the public record—whether and to what extent frontier AI developers have such insurance. Requiring some developers to purchase liability insurance coverage for tort claims could address some shortcomings of liability, and recent work has proposed mandatory liability insurance for catastrophic harms from releasing model weights. Requiring coverage in excess of solvency limits could mitigate the under-deterrence of large accidents—though insurers typically require some cap on their liability. Broadly speaking, the financial incentives immediately provided by insurance premiums could influence companies’ behaviors more reliably than the more speculative risk of future lawsuits. How well this works in practice will depend on the ability and willingness of insurers to monitor and shape the behavior of insured companies, which some have argued is often overstated. Moreover, there are other reasons that liability insurers might find it prohibitively difficult or even impossible to insure the relevant risks, given that these risks are of deeply uncertain magnitude and involve unprecedentedly catastrophic outcomes.

- Considering the implementation of liability shields carefully. As an increasing number of jurisdictions consider regulation aimed at frontier AI systems, liability shields will likely be proposed. The shields might be analogous to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, which protects online platforms from liability for content they host. Section 230 was intended to support the rapid growth of the internet by limiting the stifling effect of lawsuits. Although Section 230 may have succeeded in this goal, it may also have hindered the proper governance of social media companies in various important respects. Whether or not the enactment of Section 230 was desirable on balance, we believe that a similarly broad and unconditional liability shield would be ill-advised in the case of frontier AI companies, given the potent risks to national security and safety that increasingly capable frontier AI systems will likely pose. By contrast, conditional liability shields—which make AI companies immune to liability if they adhere to certain regulations or standards—might be one way to balance innovation and responsible governance. However, even these should be considered carefully. Conditional liability shields will tend to reduce companies’ incentives to go beyond the relevant regulatory requirements. In doing so, such liability shields could tend to ossify the development of safety practices in the AI industry. This would be a regrettable result, given how nascent our understanding of AI safety is. Whether a conditional liability shield for AI development would be advisable, and what form it might take, warrants much more attention by scholars, lawyers, and policy practitioners.

***

Frontier AI developers can take precautions to reduce the risks that their most advanced systems will increasingly pose. The importance of developing and utilizing such measures will plausibly scale with the capabilities of these systems. Tort liability is a promising tool for encouraging frontier AI companies to engage in responsible behavior; it can incentivize companies both to honor existing safety standards and to innovate in safety. Responsible development and deployment practices and reasonable care should not be incentivized via tort liability alone. Regulation and tort liability should be seen as complementary instruments of AI governance: Indeed, this is the standard approach in many other domains with safety risks, from civil aviation and nuclear power to driving and food production. To live up to its promise as a tool for reducing risks from frontier AI, however, tort law may require thoughtful and targeted modification by policymakers.

.png?sfvrsn=42cd5a2d_3)