Transnational Organized Crime and National Security: Hezbollah, Hackers and Corruption

American law enforcement efforts have become increasingly multifaceted as the government attempts to combat the continuing ingenuity and sophistication of transnational organized criminal groups. Since the publication of the first post in this series, the U.S. government has announced several significant actions taken against transnational organized crime groups.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

American law enforcement efforts have become increasingly multifaceted as the government attempts to combat the continuing ingenuity and sophistication of transnational organized criminal groups. Since the publication of the first post in this series, the U.S. government has announced several significant actions taken against transnational organized crime groups. The Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) promulgated a slew of sanctions against the financial networks of both Hezbollah and Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG). The Justice Department announced takedowns of drug trafficking rings spanning the U.S. and Mexico as well as a large-scale organized cybercrime ring composed of members from several Eastern European countries.

Organized Crime by Established National Security Threats

Hezbollah

On April 11, OFAC declared Kassem Chams, a Lebanese national, to be a specially designated narcotics trafficker and money launderer for Hezbollah—accompanying that designation with sanctions against both Chams personally and his company, Chams Exchange. OFAC asserted that the Chams Exchange was a money laundering enterprise through which Chams moved tens of millions of dollars every month for Hezbollah, the Colombian cartel La Oficina de Envigado and drug money launderer Ayman Said Joumaa, who himself was sanctioned by OFAC under the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act (Kingpin Act) in 2011. According to OFAC, Chams’s reach was global: He allegedly moved illicit funds across Australia, Colombia, Italy, Lebanon, the Netherlands, Spain, Venezuela, France, Brazil and the United States. A diagram depicting the full scope of his network can be found here. The OFAC sanctions against Cham are a component of Project Cassandra, a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)-led initiative that has targeted Hezbollah’s criminal support networks for years.

A dual citizen of Colombia and Lebanon, Joumaa has long-documented connections to both Los Zetas and Hezbollah, as the Justice Department charged him in 2011 with coordinating multiton shipments of cocaine bound for Los Zetas—a major Mexican drug cartel notorious for its violence—and then laundering hundreds of millions of dollars for the Colombian suppliers of the cocaine. The 2011 sanctions against him detailed the staggering amount of illicit funds his network laundered: up to $200 million each month.

A second set of OFAC sanctions highlights the steps that Hezbollah and its supporters have taken to avoid the U.S. government’s measures against the group. On April 24, OFAC announced that it had targeted two individuals who helped Hezbollah to evade penalties imposed by previous sanctions by acting on behalf of their family members who had been targeted for financially supporting the group.

OFAC named Belgium-based Wael Bazzi as an operative for his father, Hezbollah financier Mohammed Bazzi, and designated three companies owned by Wael Bazzi as fronts for Hezbollah’s criminal financial network. OFAC sanctioned Mohammed Bazzi in May 2018 as a specially designated global terrorist and documented his extensive financial support for Hezbollah. Wael Bazzi allegedly assisted his father in circumventing OFAC by changing the names and ostensible ownership of Mohammed Bazzi’s corporate entities that OFAC had targeted in 2018. The sanctions extended to three companies owned by Wael Bazzi, including one used as a front for his father’s continued dealings in the oil industry.

The April 24 sanctions also targeted Hassan Tabaja for allegedly acting on behalf of his brother, Adham Tabaja, a significant Hezbollah financier. On April 22, the State Department announced a $10 million reward for information on Adham Tabaja, who it declared is deeply connected to the upper echelons of Hezbollah and Islamic Jihad, a terrorist organization affiliated with Hezbollah. In addition to legally representing Adham Tabaja, Hassan Tabaja allegedly acted on his brother’s behalf while engaging in business relationships with Mohamad Noureddine, a Lebanese national whom OFAC also declared a specially designated global terrorist in January 2016.

On one side of the equation, the connections of Chams, Wael Bazzi and Adham Tabaja to previously targeted Hezbollah members demonstrate the sophistication of the organization’s criminal infrastructure, as it has responded to powerful sanctions and other punitive measures by bringing in new individuals and corporate entities to support or replace their targeted affiliates. Moreover, these sanctions expose the group’s financial machinery employed to further its terrorist mission. On the other side, the involvement and coordination of the Treasury Department, the Justice Department and the State Department illustrate the comprehensive approach the U.S. government has adopted in its efforts to cripple Hezbollah’s criminal activities.

Cybercrime and Hacking Activities by Organized Criminal Groups

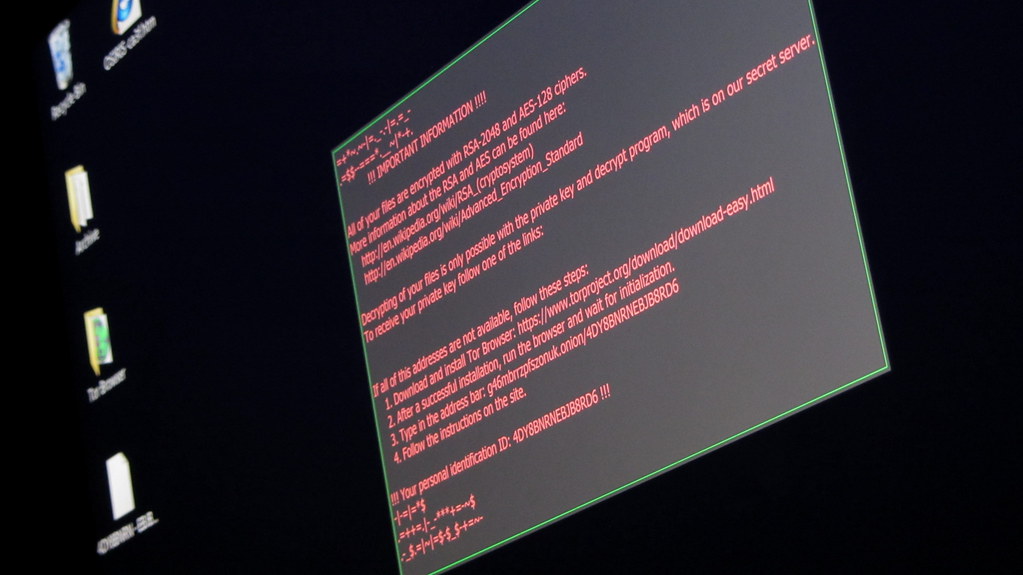

Ransomware

Several American municipalities have suffered debilitating ransomware hacks in the past few months, in which malware disables a computer system until the owner pays a sum demanded by the hacker—often in Bitcoin. The city of Baltimore is the most prominent victim. Originally targeted on May 7, the city’s computer infrastructure has remained crippled for weeks, as city officials refused the $100,000 in Bitcoin ransom. The message that announced the Baltimore hack read, in part, “We won’t talk more, all we know is MONEY! Hurry up!”

The Baltimore hack has received the most publicity, but ransomware attacks have been reported around the country, including against the baggage computer system in Cleveland’s Hopkins airport; the municipal servers in Imperial County, California; and the websites of Jackson County, Georgia. Some municipalities, like Imperial County, have refused to pay the ransom and have spent weeks rebuilding their paralyzed systems. Others, like Jackson County, have acquiesced to the hackers’ demands.

There is no indication that these hacks have been executed by the same perpetrators, but investigators suspect that the Cleveland airport attack was carried out by an organized criminal group. In recent years, law enforcement agencies both in the U.S. and abroad have issued warnings about the prevalence of ransomware attacks by organized crime groups.

This spree of hacks has sparked speculation that hacking groups are using ransomware software originally developed by the National Security Agency (NSA). In 2017, an anonymous group calling themselves the Shadow Brokers began publicly posting online secret code stolen from the NSA. Numerous experts, including security consultants working with affected cities, have posited that the perpetrators of these recent attacks are using NSA software that was leaked by the Shadow Brokers. The agency has vigorously denied that its software was used in the Baltimore hack but has not commented about the other attacks, which, according to some experts, are occurring on an almost daily level. Whatever the cause, there is no indication that these hacks will cease and—given the relatively weak cyber defenses employed by most American municipalities—they will likely continue or even increase in the future.

GozNym Malware

On May 16, the U.S Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Pennsylvania announced the takedown of a massive transnational organized cybercrime network that infected roughly 41,000 computers in the U.S. and Europe and attempted to steal over $100 million. The group used GozNym malware—named after its combination of two pre-existing strands of malware, Gozi and Nymaim—to surreptitiously penetrate computers, steal users’ bank account information and use that information to steal money from their accounts. The defendants then allegedly attempted to launder the stolen funds through bank accounts they controlled.

The indictment contained charges against 10 defendants residing in Russia, Bulgaria, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. The investigation was a collaboration between the Justice Department; Interpol; and prosecutors in Georgia, Ukraine, Moldova, Germany and Bulgaria. According to the announcement, the GozNym group was a textbook example of “cybercrime as a service”: The defendants separately advertised their criminal hacking capabilities on underground criminal forums and then formed the group to combine their skillsets.

The five defendants who resided in Russia were not arrested and remain at large. Their freedom and the reluctance of Russian authorities to cooperate with the transnational investigation is another sign of Russia’s ongoing tolerance, if not outright sponsorship, of organized cybercrime groups that operate within its borders.

Corruption and Destabilization by Narcotrafficking Organizations

The United States

A Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officer was sentenced on April 18 in the Central District of California to more than 12 years in federal prison for his role in a large-scale narcotics distribution ring. Manuel Porras Salas, a 25-year CBP veteran previously stationed at Los Angeles International Airport, and his wife, Sayda Powery Orellana, had been found guilty during a December 2018 trial of several narcotics trafficking and money laundering charges.

According to the government, Salas and Orellana were responsible for shipping hundreds of kilograms of drugs throughout the Midwest and laundering the proceeds in accounts held under Orellana’s name. Their scheme was unearthed when a commercial truck driver was detained by authorities in Gallup, New Mexico, and found to be carrying 260 kilograms of heroin, cocaine and marijuana. The driver fingered Salas and Orellana as his superiors in the scheme and described multiple drug runs he had made throughout the country at their direction.

Mexico

On May 17, OFAC unveiled a host of sanctions under the Kingpin Act aimed at several people connected to CJNG and an allied cartel, Los Cuinis. OFAC claimed that Isidro Avelar Gutierrez, a Mexican magistrate judge, had received bribes from CJNG and Los Cuinis in exchange for ruling in favor of senior cartel members who appeared before him. In addition to Avelar, OFAC sanctioned Gonzalo Mendoza Gaytan, known as “El Sapo”—a high-ranking CJNG leader who, OFAC declared, is responsible for running the cartel’s operations in the coastal town of Puerto Vallarta as well as for numerous kidnappings and killings in Mexico. The sanctions targeted six other Mexican nationals for alleged money laundering on behalf of CJNG members as well as six Mexican companies working on behalf of CJNG.

Much less known in the United States than its rival, the Sinaloa Cartel, CJNG has emerged rapidly as a leading cause of violence in Mexico and drug trafficking into the United States. In October 2018 the Justice Department declared CJNG to be a “transnational organized crime threat” and the May 17 sanctions are the 10th set of OFAC measures imposed against the cartel and its allies. A diagram depicting the Kingpin Act sanctions can be found here.

Also on May 17, OFAC sanctioned the former governor of the Mexican state of Nayarit, Roberto Sandoval Castaneda, for sharing confidential state information with several cartels—including CJNG—in exchange for bribes and protection. The sanctions announcement also accused Sandoval Castaneda of misappropriating state assets during his tenure as governor from 2011 to 2017 and his previous time as mayor of Tepic, Nayarit’s capital, from 2008 to 2011. Sandoval Castaneda is not the only former Nayarit state official to be targeted by American law enforcement in recent months: The state’s former attorney general, Edgar Veytia, pleaded guilty to drug trafficking charges in the Eastern District of New York in January.

OFAC designated Sandoval Castaneda under Executive Order 13818, which implements the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act—issued to combat international corruption and human rights abuses. OFAC also designated Sandoval Castaneda’s wife, son and daughter and four Mexican corporate entities controlled by the Sandoval Castaneda family. A diagram depicting the full scope of Sandoval Castaneda’s corruption and the sanctions against his family can be found here.

The Mexican government moved decisively after OFAC’s announcement, seizing 11 properties belonging to Sandoval Castaneda in and around the city of Tepic and denouncing Avelar Gutierrez—perhaps signaling new President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s intent to keep his campaign promise of taking down government officials, particularly judges, who cooperated with cartels.

Like its archrival CJNG, the Sinaloa cartel has also been on the receiving end of American law enforcement actions in recent weeks. On May 21, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Southern California unsealed indictments against 43 members of a methamphetamine distribution ring with ties to the Sinaloa cartel. The indictments described a complex network that shipped methamphetamine and gamma-hydroxybutryate (GHB) to dozens of regional distributors across the United States and United Arab Emirates. The alleged proceeds of those sales were subsequently returned through shipments of cash, structured cash deposits in bank accounts and online payment transfer systems like Venmo, Zelle and PayPal.

Although the opioid crisis is currently dominating headlines, Mexican cartels have aggressively moved into the methamphetamine trade in recent years, encouraged by the availability of bulk Chinese chemicals necessary to mass produce the drug. Equally important, the cartels’ bottom lines benefit from controlling the production themselves, without having to share their profits with the Colombian drug trafficking organizations that typically supply cocaine to the Mexican cartels. The resulting methamphetamine shipped to the United States is much more pure than that made by small-time domestic producers and has resulted in an 800 percent increase in methamphetamine overdoses in the United States over the past decade, from 0.4 per 100,000 people in 2008 to 3.2 per 100,000 people in 2017.

Guatemala

Guatemalan presidential candidate Mario Amilcar Estrada Orellana was indicted by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York on April 17 for conspiracy to import cocaine into the U.S. and a related weapons charge of conspiring to use and possess machine guns. The complaint details how Estrada and a co-conspirator, Juan Pablo Gonzalez Mayorga, allegedly solicited roughly $12 million in financial support for Estrada’s presidential campaign from the Sinaloa cartel. In return, they supposedly promised that, if Estrada were elected president, he would ensure that the Guatemalan government would support the cartel’s cocaine trafficking into the United States.

Gonzalez was allegedly the chief point of contact for the purported Sinaloan representatives, who were actually confidential sources for the DEA. In addition to suggesting that Estrada would appoint Sinaloan cartel members to positions within the Guatemalan Ministries of Interior and Defense, Gonzalez allegedly promised the cartel free access to Guatemalan airports and ports and asked if the cartel could assassinate Estrada’s political rivals. Estrada is the latest in a long line of Guatemalan politicians, including current President Jimmy Morales and former President Otto Pérez Molina, to be credibly accused of corruption.

The Northern Triangle

The Departments of State and Defense came under scrutiny in April after releasing a list of senior government officials from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala who were credibly linked to either narcotrafficking activities or corruptly accepting campaign funds that were criminal proceeds. Those three countries form the “Northern Triangle,” a hotspot of political instability and violence marked by a history of civil wars in the 1980s that left a legacy of weakened civil institutions and state power. Critics such as Rep. Norma Torres (D-CA) called the list a “sham,” arguing that it included only officials who were already punished for their crimes—meaning many officials whom the U.S. strongly suspected were involved in narcotrafficking or related corruption were omitted.

The State Department responded swiftly to the public criticism by releasing a revised list in May, including many officials who were previously left off, like Estrada and José Luis Merino, the vice minister of foreign investment and funding in El Salvador’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Luis has been accused of using his connections with ALBA Petróleos—a Salvadorian subsidiary of Venezuela’s state-operated oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela S.A.—to enrich El Salvadorian political elites. He was also investigated last year by U.S. officials on suspicion of corruption and drug trafficking. The revised report called corruption “endemic and systemic” in the Northern Triangle, connecting instability in the region to the presence of transnational organized crime and citizens’ lack of faith in their public institutions.