Troops Clash Along Chinese-Indian Border; U.S. and China Hold High-Level Diplomatic Talks

Lawfare's biweekly roundup of U.S.-China technology policy and national security news.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

At Least Twenty Dead in Clash at Chinese-Indian Border

On the night of June 15, according to a statement released by the Indian military, at least 20 Indian soldiers died after a “violent face off” with Chinese troops in the Galwan Valley near the line of actual control, a demarcation that separates Chinese-held territory from Indian-held territory along a contested part of the China-India border. A Chinese military spokesperson said that the incident had resulted in “casualties,” but the Chinese government has not provided further details. Hu Xijin, the editor of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) mouthpiece the Global Times, said on twitter that Beijing decided to withhold the number of Chinese deaths because China wanted “to avoid stoking public mood.” Neither Chinese nor Indian troops were carrying firearms during the fighting, in accordance with a 1996 agreement reached between New Delhi and Beijing to reduce the risk of escalation. Instead, soldiers wielded iron bars and threw rocks and punches on steep, jagged terrain. Many of the deaths occurred when troops fell off mountain ridges.

Indian and Chinese military leaders met on June 16 in an effort to defuse the situation. Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi spoke with Indian Minister of External Affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar by phone on June 17, and the two agreed that “neither side would take any action to escalate matters.” And on June 19, China released 10 Indian troops it had takenprisoner in the fighting. But some experts say that the possibility of further tension remains high: Satellite data reveals that, as of June 18, People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops still occupied some 23 miles of territory taken from India over the past few weeks.

The two sides have offered conflicting accounts of the events leading to the confrontation. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian accused Indian troops of crossing the line of actual control twice on June 15 and “provoking and attacking Chinese personnel, resulting in serious physical confrontation between border forces ….” Meanwhile, the Indian government has said that the PLA staged an ambush in an area that they had agreed to vacate. On June 17, Indian Prime Minister Nahrendra Modi—seen by critics as a promoter of a bellicose Hindu nationalism—said, “The sovereignty and integrity of India is supreme, and nobody can stop us in defending that. ... India wants peace, but if provoked India is capable of giving a befitting reply.” Chinese President Xi Jinping, who has adopted more aggressive and nationalistic foreign policy in recent months, has yet to comment publicly on the matter.

Tensions have been high in the Galwan Valley since May 10, when hundreds of Indian and Chinese soldiers brawled, resulting in a number of serious injuries but no fatalities. The immediate catalyst of that fight remains unclear: Analysts note that on occasion People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Indian troops patrolling the area encounter each other, and that shouting or even fistfights are not uncommon. But the brawling may have been motivated by deeper geopolitical concerns. Some analysts argue that Beijing has taken a more confrontational approach in the Galwan Valley in light of political developments in New Delhi. In August 2019, Modi issued a presidential order that partitioned the former state of Jammu and Kashmir into two separate “union territories”—Ladakh, and Jammu and Kashmir—and eliminated constitutional provisions that had granted Jammu and Kashmir significant autonomy. India drew up border lines for Ladakh that included Aksai Chin, a region controlled by China but also claimed by India.

The Aksai Chin region provides transportation routes between Xinjiang and Tibet, two provinces where Beijing has sought to quell political dissent among ethnic minority groups through heavy surveillance. (In the case of Xinjiang, China has sent more than a million residents to detention centers.) The Karakoram Highway, a strategic trade and supply route that connects China with Pakistan, also runs through Aksai Chin. In response to India’s political reorganization, the Global Times tweeted: “China opposes #India putting Chinese territory in the western section of the border under its administration, which affects China's territorial integrity and sovereignty. It is ‘unacceptable and void’.”

Following the reorganization, India also stepped up infrastructure projects in Ladakh. These developments included new construction on the Darbuk-Shyokh-Daulat Beg Oldie (DSDBO) road, which runs close to the line of actual control and includes a number of military outposts and air strips.

On May 18—more than a week after the initial brawl—the Global Times claimed that India was illegally constructing defense facilities in the Galwan Valley and noted that the Chinese military would send reinforcements to protect the PRC’s territorial sovereignty. The Indian military also sent in thousands of reinforcements after the May 10 confrontation. For a few weeks after the brawl, deescalation talks made slow and significant progress. While meetings on May 22 and May 23 produced no results, diplomatic talks on June 5 and military talks on June 6 yielded an agreement “to peacefully resolve the situation in the border areas in accordance with various bilateral agreements and keeping in view the agreement between the leaders that peace and tranquility in the India-China border regions is essential for the overall development of bilateral relations.”

Following the fighting on June 15, protests have spread in various Indian cities, and some groups called for a boycott of Chinese goods. Analysts worry that the muscular foreign policies endorsed by Modi and Xi, respectively, may limit the options available to each side as they seek to deescalate tensions.

United States and China Hold First Senior-Level Talks Since January

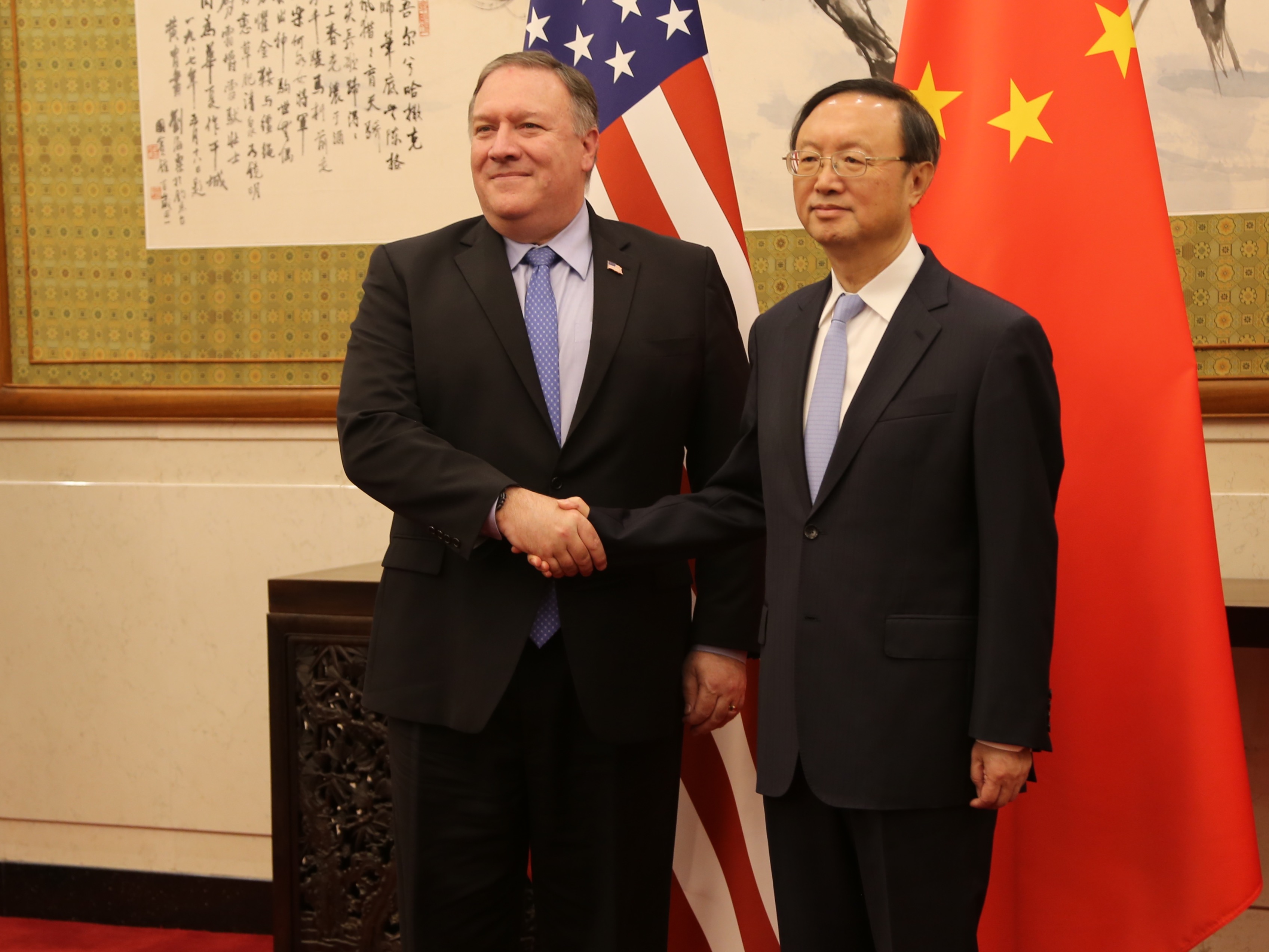

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reportedly met this week in Hawaii with China’s top foreign policy official, Yang Jiechi. The meeting, which took place on June 17, was aimed at easing recent tensions between the two countries and spanned a range of issues. This is the first senior-level meeting between U.S. and Chinese officials since January, when Vice Premier Liu He signed the phase one U.S.-China trade deal in Washington. Pompeo himself has not met with Chinese leaders since he last saw Yang in August 2019, though the two have spoken by phone since the outbreak of the coronavirus. Reports of this week’s meeting first broke on June 12, with anonymous U.S. officials commenting that it was being kept tightly under wraps. After the meeting took place, the State Department acknowledged it but divulged few details—noting mainly that the two sides discussed the need for “fully reciprocal” deals on trade and security. U.S. and Chinese officials both claimed that the other side requested the meeting in Hawaii.

The diplomatic meeting comes as U.S-China tensions over a host of issues have reached their highest level in decades—with President Trump in May going so far as to threaten to cut ties with Beijing. Relations have been strained amid U.S. accusations that China mishandled and covered up the coronavirus outbreak. Since then, Beijing’s new proposed national security law for Hong Kong—which threatens to diminish the city’s autonomy—and its aggressive posturing toward Taiwan have further stoked tensions. In a break with the country’s traditional approach to diplomatic affairs, Chinese officials and public figures have widely responded with what Western and Chinese media refer to as “wolf warrior” diplomacy. Under this new approach, officials have lashed out combatively at Western critics; they have also criticized the United States’s own human rights record, pointing to its handling of protests surrounding the death of George Floyd. U.S. officials, including Pompeo, have denounced such Chinese remarks as hypocritical propaganda.

In this context, media commentators have interpreted the Hawaii meeting as an effort to repair relations. The talks follow small signs that China is rethinking its hard-line approach to diplomacy. Many Chinese analysts have started to view “wolf warrior” diplomacy as backfiring and have increasingly advocated easing tensions with Washington. (Some U.S. experts have argued that China’s latest “wolf warrior” tactics reflect a split in China over how to conduct diplomacy.) In other areas, U.S.-China hostility has ratcheted down slightly. For instance, China recently eased its ban on U.S. airlines landing in the country, prompting the Trump administration to move away from its plans to further restrict flights by Chinese carriers. China is also taking small steps to implement its agricultural-import commitments under the phase one trade deal. This month, it transferred authority for such purchases from the Ministry of Commerce to the less-politicized Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs.

Still, many observers caution that the latest high-level meeting will have limited effect. While it may signal that U.S.-China communications “have not been devastated,” in the words of one prominent Chinese international relations analyst, the meeting “is unlikely to defuse the tensions that have been building up on almost every front.” After the meeting, one U.S. official suggested it may have resulted in little concrete progress, describing the Chinese side as not “forthcoming.”

These developments come as Beijing is experiencing a second outbreak of the coronavirus, which officials describe as “extremely severe.” As of June 18, roughly 150 cases had emerged in the city. The outbreak has been traced to the Xinfadi food market—a complex of trading halls and warehouses that supplies 80 percent of Beijing’s fruits and vegetables. Commentators believe the resurgence could cause embarrassment for Chinese officials, who have latelytouted their country’s effective handling of the virus. It could also lead to an uptick in anti-Western rhetoric: State media this week have already suggested that this outbreak—as well as the coronavirus itself—may have originated in Europe. So far, Beijing has closed its schools, shut down neighborhoods in various districts of the city and tested more than 350,000 residents.

Following the Pompeo-Yang meeting, tensions flared again as China condemned the United States for enacting the Uighur Human Rights Policy Act of 2020, which Trump signed into law on June 17. The new law empowers the president to sanction Chinese officials involved in the mass detention of Chinese Uighur and other minorities. Meanwhile, the meeting also coincided with increased scrutiny of Trump’s relationship with President Xi in the United States. On June 17, U.S. media outlets published excerpts from former National Security Adviser John Bolton’s forthcoming memoir about his experience in the Trump administration. The excerpts allege that Trump had requested Xi’s assistance in his 2020 presidential election campaign and expressed approval to Xi of China’s Uighur detention policies. China has deniedany intention to interfere with U.S. elections.

Zoom Blocks Account of U.S.-Based Activists at Beijing’s Request

Zoom blocked the account of U.S.-based Chinese activists Zhou Fengsuo and Wang Dan, as well as Hong Kong-based Lee Cheuk-yan, after they organized and participated in events via Zoom to commemorate the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. In a statement to Axios, the video conferencing firm said that it suspended Zhou’s account to “comply with applicable laws” in China, where the government censors discussion of the 1989 Tiananmen protests, during which the Chinese military killed hundreds—if not thousands—of students advocating for economic and political reform. The news came as authorities in Hong Kong sought to enforce a ban on the city’s annual June 4 vigil for the Tiananmen incident.

In a separate June 11 statement, Zoom acknowledged that the Chinese government had asked it to terminate accounts and suspend sessions associated with the Tiananmen Square protests. In three of the four cases, Zoom complied, on the grounds that significant numbers of Zoom accounts from mainland China were scheduled to participate. “Zoom does not currently have the ability to remove specific participants from a meeting or block participants from a certain country from joining a meeting,” the statement said. Zoom also said it “is developing technology over the next several days that will enable us to remove or block at the participant level based on geography.” Zoom did not make clear which Chinese law the events had violated.

The incident comes as experts have raised questions about the company’s ties to China. In a wide-ranging report on Zoom’s cybersecurity vulnerabilities published in April, CitizenLab found that Zoom used subpar encryption keys that sometimes passed through company servers in China, even when all call participants were outside the PRC. “Zoom may be legally obligated to disclose these keys to authorities in China,” the report explains. Zoom also owns three companies in the PRC and employs more than 700 software developers in the country.

In light of these and other cybersecurity concerns, some governments and companies have imposed restrictions on Zoom use. Taiwan banned official use of the service in early April, and the German government restricted its use under certain circumstances. After an FBI warning, the U.S. military blacklisted most versions of the service for official use. SpaceX and Google have also instructed their employees not to use Zoom.

Censorship on Zoom adds to growing concerns over the CCP’s campaign to censor discourse beyond its borders. In late May, YouTube admitted that the company’s algorithms were automatically deleting Chinese language comments that were critical of the CCP. YouTube said the deletions were accidental and that they had fixed the problem. WeChat, a Chinese messaging, gaming, and payment service, censors users outside of the PRC and reportedly provides data on both foreign and domestic users to Chinese security services. And TikTok, a popular video-streaming app from Chinese social media company ByteDance, came under scrutiny in 2019 for censoring U.S. users in accordance with Chinese law.

Experts have also raised concerns about China’s aggressive information campaigns targeting foreign audiences. On June 12, Twitter announced that it had taken down more than 170,000 accounts linked to Beijing. The accounts were“spreading geopolitical narratives favorable to the Communist Party of China (CCP), while continuing to push deceptive narratives about the political dynamics in Hong Kong.” Meanwhile, the European Commission said this past week that China, along with Russia, had been responsible for a “huge wave” of disinformation related to the coronavirus pandemic. The Investigation Bureau of Taiwan reported last month that accounts linked to mainland China had run extensive information campaigns to spread CCP narratives about the coronavirus. And Australia’s foreign minister said on June 16 that China has spread disinformation that “contributes to a climate of fear and division” in the wake of the pandemic.

In Other News

The Trump administration on June 15 signed off on a rule change that formally allows American companies to cooperate with Huawei on technical standards for 5G technologies. The announcement comes after a May 2020 decision to tightenrestrictions on Huawei by forbidding overseas manufacturers from selling semiconductors produced with U.S. components or software to the telecom giant. The Commerce Department first announced it would add Huawei to a government blacklist in May 2019. But the Commerce Department has continued to delay the ban’s implementation—which is now scheduled for August, after a final three-month extension was granted in May—because of pressure from U.S. companies, which view trade with Huawei as a key source of revenue and growth. Speaking about the decision to allow technical cooperation, U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross said that “[t]his action recognizes the importance of harnessing American ingenuity to advance and protect our economic and national security.” The new rule will allow U.S. companies to exchange information with Huawei and build joint standards, even if those U.S. companies do not ultimately receive a formal license from the U.S. government to export component parts to the Chinese telecommunications giant.

Chinese scientists reported progress in developing quantum encryption technology for satellites, a breakthrough that may give the PRC advantages in satellite communications and surveillance. In April of this year, NASA released research plans to develop the same kind of technology. The United States, China and Russia view satellite technology as integral to national security, since both governments and commercial enterprises increasingly rely on them for communications and military functions. Experts have pointed out that security concerns related to satellite technology have been compoundedby a dearth of international standards governing behavior in the expanding domain.

President Trump signed into law the Uighur Human Rights Policy Act of 2020, which requires the president to sanctionChinese officials responsible for human rights abuses in Xinjiang, where the Chinese government has imprisonedmore than a million people in a network of detention and forced labor camps. Within 180 days, the president must provide a report to Congress identifying the individuals responsible for human rights abuses in Xinjiang. The sanctions will include blocking access to U.S. assets and preventing blacklisted individuals from receiving a U.S. visa.

Commentary

In Foreign Affairs, Lee Hsien Loong charts paths forward for the United States and China to adjust to each other’s role on the global stage—and the consequences of these paths for the Asia-Pacific region. In the New York Times, Vijay Gokhaleargues that China seeks to operate within the global order, not overthrow it. The Financial Times editorial board analyzesseismic changes in the United Kingdom’s relationship with China, as the former nation increasingly prioritizes security over economic ties. Writing for the Mercatus Center, Michael Auslin discusses divides that the coronavirus has deepened between China and Western nations.

The Wall Street Journal editorial board explores the global consequences of the United States’s recent efforts to decouple technologically from China. Writing for Bloomberg, Shuli Ren unpacks bureaucratic and management challenges facing Chinese tech champions. In the Los Angeles Times, Anja Manuel and Melanie Hart explain how the United States can counter Chinese efforts to dictate global technology standard-setting processes. At the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Scott Kennedy and Shining Tan observe that Western companies have seemingly not heeded Washington’s appeals to decouple their production and supply chains from China.

For Lawfare, Peter E. Harrell discusses Trump’s recent announcement to eliminate special trade and investment treatment for Hong Kong. Preston Lim analyzes a Canadian court’s dismissal of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou’s application to end extradition hearings. Justin Sherman and Tianjiu Zuo examine implications of U.S.-China decoupling for the United States’ energy supply grid.