The Trump Impeachment and the Question of Precedent

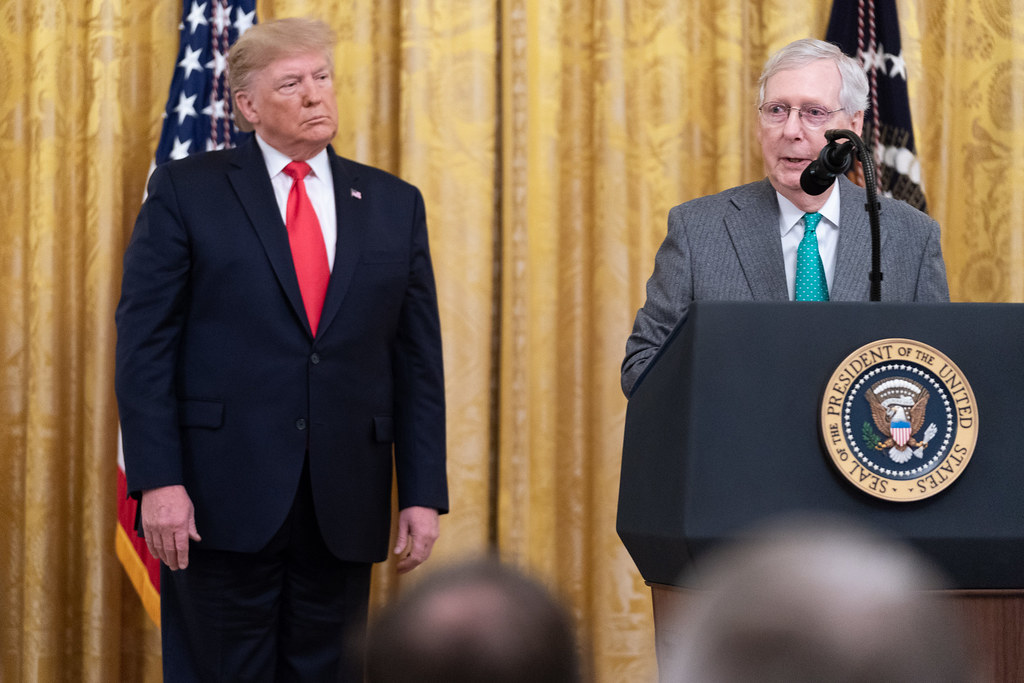

In speeches sounding the alarm about “toxic” precedent, Sen. Mitch McConnell has set forth a questionable view of the law of impeachment with serious implications for the future of this constitutional remedy.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On Dec. 17 and Dec. 19, 2019, and Jan. 8 of this year, speaking from the Senate floor, Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell made the case that the Trump impeachment was setting a “toxic” and “nightmarish” precedent “deeply damaging to the institutions of American government.” The House’s actions, said the majority leader, would ensure that impeachment became routine, a “constant part…of the political background noise” and of the “arms race of polarization.” It would be transformed into a weapon with which to “paralyze future Senates with frivolous impeachments at will.” The Senate, in his view, is now obligated to act as a brake to prevent a “constitutional crisis.”

McConnell did not speak directly or in much detail as to the merits of the case against Trump. He was more focused on defining in fundamental terms the constitutionally acceptable standards for impeachment, and it is this position that should not be overlooked as public and press attention are more naturally drawn to the specific charges against Trump and the question of whether the trial will include witnesses.

To the extent that there has been discussion of constitutional precedent, it has occurred primarily in the context of the struggle over witnesses. McConnell has embraced the two-stage process that the Senate adopted for the Clinton impeachment trial, which would defer the decision on witnesses until after opening arguments and initial questions from the senators. The very different “toxic,” “nightmarish” precedentthat the senator is warning against is far broader in scope and significance. He sees what the House has done as threatening a dangerous “cheapening [of] the impeachment process” that could lead to the “impeachment of every future president of either party.”

In defining what kind of precedent he opposes, McConnell has revealed the kind that he favors—and that he hopes will emerge from the Senate’s disposition of the House case. His is a troubling argument. Recognizing its problematic features—their implications for the “law” of impeachment in the future—does not depend on any particular view of the merits of the impeachment case against Trump.

Broken out, these are the component parts of McConnell’s argument and the problems with the “precedent” he would establish.

“Rushed”

McConnell argues that the House rushed its inquiry and so failed to adequately consider the grounds for impeachment. He contrasts this rush to judgment with the Nixon proceedings, which ran for a year and a half, and the Clinton impeachment, which followed “years of investigation.”

There is, of course, no constitutional basis for this concern with an expedited inquiry. In any legal case involving allegations of impeachable conduct, the House might have to move with dispatch if the evidence is compelling that the president has engaged in serious, disqualifying misconduct and cannot be entrusted with his office. An expedited inquiry, which opponents may choose to label as “rushed,” may be the only responsible congressional action in the circumstances. This would certainly be a case where the president’s actions exposed him or her as a threat to national security.

It is also curious that McConnell cites the Clinton case as an example of the methodical approach—avoiding a “rush to judgment”—that he is advocating. In that instance, House Republicans conducted impeachment proceedings for less than two months. The “years of investigation” to which McConnell refers are the rash of independent counsel inquiries into allegations against Clinton. If McConnell is seeking an example of institutional damage and troubling precedent, he would surely find it in an impeachment in which the House relied almost entirely on the controversial record assembled by an officer of the executive branch who was the central “witness” in the impeachment process.

“Partisan”

McConnell also argues that this impeachment process has suffered from extraordinary, disqualifying levels of partisanship. The House action was “purely partisan,” he stated, and a “partisan crusade.” He contends that a credible impeachment would require party crossovers and implied that previous impeachments, like Clinton’s, were not “purely partisan” because a handful of members broke with their party in voting on impeachment or conviction.

McConnell’s history is weak. More than 90 percent of the House Republicans voted for Clinton’s impeachment; more than 90 percent of Republican senators voted for convicting him. By any measure, among lawmakers, there was overwhelming Republican Party support for ousting a Democratic president from office. McConnell’s professed claims of historically unprecedented partisanship founder on the pointless distinction between fully party-line and just-over-90-percent party-line support.

And still another measure of partisanship in the Clinton case, unhelpful to McConnell’s argument, is the difference between congressional Republican support for ousting Clinton and public opinion among Republicans in the electorate. Polls in November 1998 showed that almost 30 percent of Republicans in the country opposed impeachment—almost 40 percent believed that the Starr investigation on which the Republican case for impeachment was based was too partisan. The party politicians forged ahead nonetheless. They were responding to the most “partisan” party members who were determined to drive Clinton from office. When McConnell refers, as he did on the floor, to an impeachment process willed by “one part of one faction” of “angry partisans,” he could have been describing the Clinton experience.

Of course, House Republican opposition to Trump’s impeachment rose to 100 percent (not counting Rep. Justin Amash of Michigan, who voted as an independent). Ninety-nine percent of Democrats present and voting who cast either a “yeah” or “nay” vote supported impeachment. Why is one party at 99 percent more “partisan” in voting for impeachment than the other at 100 percent in opposing it?

But there is another move evident in McConnell’s test for “pure partisanship.” He sets up a default rule that one party’s partisanship in defense of a president is not “pure partisanship” and this particular charge lies only against the party making the case, however strong, for impeachment.

In a highly polarized political environment such as ours, a congressional party’s rallying to the president’s defense for as long as it conceivably can is more likely than not. McConnell’s test for “partisanship” gives a president who manages to maintain party support another card to play in arguing that he or she is a victim of rank politics in a constitutionally defective process. The divide between the parties on the impeachment question becomes decisive evidence of undue partisanship.

It is, of course, reasonable to be concerned about partisan abuse of impeachment, but partisan division cannot be an acid test of whether a president has committed an impeachable offense. It is not difficult to imagine that in a social media-shaped world of “alternative facts,” a political party concludes that it is both in its political interest and feasible to defend egregious misconduct bearing directly on fitness for office and stick with the president. McConnell would endow this strategy with normative force for future impeachments as well as an objection to the impeachment of Trump.

Crime

McConnell argues that the House articles of impeachment are defective because they do not allege a crime. (The House Judiciary Committee did allege that Trump’s conduct in soliciting foreign intervention in aid of his personal political goals was criminal, but the articles omit this charge.) The Republican leader makes much of the absence of an “actual crime known to our laws,” which he also describes as “clear, recognizable crimes.” He concedes that the commission of a crime is “not a strict limitation” on the range of impeachable offenses, but he suggests that it should become the norm. Unless a crime can be alleged and proved, he contends, the door will swing open to “subjective, political impeachments.” He gives as an example of what is “subjective” and “political” the “abuse of power” charge against Trump, which he dismisses as “vague.”

There are a host of problems with the McConnell approach, not the least of which is the incentive for partisans to allege, if they do not contrive, “crimes” as the basis for impeachment. Critics of the Clinton impeachment alleged that Republicans and adversaries of the president did just that, manufacturing impeachable “high Crimes” out of the material provided by the discovery of an extramarital relationship. Once they learned of it, these critics argue, Clinton’s opponents set a perjury trap, and then converted President Clinton’s attempt to avoid acknowledging embarrassing and inappropriate behavior in his personal life into the impeachable “high Crimes” of perjury and “obstruction.”

But most dangerous is the wide swath of potential misconduct that McConnell’s view would remove from the scope of potentially impeachable offenses. Presidents could abuse power and not commit a crime, or engage in the clearest abuse of power when the associated “legal” offense is more contestable than the abrogation of constitutional responsibility. As McConnell would have it, lawyers would come to dominate the proceedings; the language of impeachment becomes the language of law.

Hamilton’s well-known discussion of impeachment in Federalist No. 65, in which he describes impeachable offenses as those which “proceed from the misconduct of public men” and “are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL,” is hard to reconcile with McConnell’s position. Where Hamilton sees room for “abuse or violation of some public trust,” McConnell sees in “abuse of power” a “vague phrase.”

“Policy”

McConnell depicts the charge against the president for seeking assistance from Ukraine in his reelection campaign as an allegation of what the Founders termed “maladministration”—a charge arising out of conflicts with the president over policy. The Founders expressly excluded maladministration as a ground for impeachment and removal, concerned, as James Madison put the point, that “so vague a term will be equivalent to a tenure during the pleasure of the Senate.” McConnell seeks to exploit this constitutional defense by dismissing the testimony against the president from administration diplomats and national security officials as expressing little more than frustration with his failure to adhere to established American policy toward Ukraine. The senator contends that the House Democrats simply “disagree with a Presidential act and question the motive behind it.”

This characterization of “policy difference” is more than a highly contestable characterization of the testimony before the House: McConnell’s underlying conception of what constitutes such a “difference” would expand the availability of this defense against presidential impeachment in the future. The witnesses called by the House did not dispute that the president could hold a different view of American policy toward Ukraine or act to change it. But their testimony convinced a majority of the House that he undercut established policy, including withholding congressionally appropriated aid for Ukraine, for personal and political, not policy, reasons. Of course, the more significant a policy, such as one important to national security, the more serious is the constitutional violation when the president casts policy aside to pursue personal political self-interest.

There is a serious risk that, on McConnell’s theory, Congress could be acting unconstitutionally to impeach a president for a policy dispute if the misconduct alleged has any arguable connection to the president’s policymaking function. Stated differently, a president would be on safe ground if the misconduct arose out of his or her activities within the policy sphere and could be characterized, in McConnell’s words, as just using “bad judgment” or “doing a bad job.” On this view, Trump’s solicitation of foreign government support for his reelection in the course of superintending the nation’s foreign relations is not impeachable, while Bill Clinton’s inappropriate relationship with a White House intern—a personal matter unconnected to policy—would be.

Should McConnell succeed in building this understanding of maladministration into impeachment precedent, future presidents would have a handy tool for dressing up serious misdeeds as somehow connected to policy disagreement with their critics.

The Role of the Courts

McConnell argues that if an administration resists the cooperation that a House calls for in an impeachment inquiry, the House is obligated to appeal for assistance to the courts—to pursue “more evidence through proper legal channels.” The House, according to this viewpoint, has one of two choices: negotiate a settlement with the president or “the third branch of government, the Judiciary, addresses the dispute between the two.” McConnell charges the House with rejecting either course, “because they didn’t want to wait for due process.”

Of course, the House is free to solicit judicial intervention. Having “the sole power to impeach” under the Constitution, it is not required to do so. There is also a powerful case for keeping the courts as far away as possible from the conflict between the president and the Congress in an impeachment. A more prominent role for the courts in impeachment, such as potentially involving them in major or decisive rulings on evidence, could lead to the impeachment process version of Bush v. Gore—another occasion when the Supreme Court, as it did with its ruling in the 2000 Florida recount, may act with the effect of determining who occupies the Oval Office.

The courts will necessarily play a role if the president is facing both an impeachment and a criminal investigation, as happened in both the Nixon and Clinton episodes, and the courts in the course of overseeing the latter cannot help but influence the former. But where this is not the case, the courts risk being absorbed into a battle with a heavy cost to their own credibility as institutions functioning in nonpartisan fashion, outside the theater of direct political combat. McConnell’s version of constitutional impeachment precedent would put them in the middle of the fight.

“Undoing” an Election

McConnell insists that this impeachment is an illegitimate “undoing” of the last election. This is another bar-raising move. If partisans who would like to be rid of a president discover plainly impeachable conduct, the McConnell theory of election “undoing” means that the case for impeachment is fatally contaminated by the prior record of strong opposition, which may well include calls for impeachment. Of course, Democrats in 1974 were pleased to put Nixon out to political pasture, and the Republicans who hounded Clinton hoped for the same outcome—disgrace and ouster—with a wide variety of charges and investigations throughout his presidency. None of this constituted an “undoing” of an election. After all, the conviction of Trump would initiate a Pence presidency, hardly the “undoing” of the 2016 election.

***

Add all these arguments together, and McConnell is plainly imposing questionable constitutional boundaries around impeachment. As he sees it, regardless of the circumstances, a House should not move too quickly, and it must await rulings from the courts in the event of evidentiary and privilege disputes with the president. The existence of sharp disagreement between the parties, which is common, becomes excessive “partisanship” that should stop impeachment procedures outright. What’s more, impeachments are disfavored unless the president has committed a crime, and if the president can allege any connection between his conduct and the making or modification of policy, then the impeachment is a constitutionally indefensible extension of a “policy” dispute. McConnell asserts these particular limits within an umbrella principle that impeachments are undemocratic, an affront to the electoral process and an “undoing” of the president’s election.

The demagogic presidency, the one the Founders most feared, is built around the personal will of the leader who has contempt for constitutional and other constraints on his or her power, intolerance for the routinely vilified opposition, a zeal and capacity for disseminating falsehoods and for creating alternative facts, and a tight grip on followers and party. Impeachment is a crucial remedy for this threat. In the name of protecting democratic institutions, McConnell is arguing for limits on this remedy, which may emerge from the Trump experience as new “precedent” that future demagogues will find much to their taste.