On Trump’s Conflict with the Russia Investigation, His Question for McCabe, and the Defense of Norms

The possibility that the president will reject full cooperation with the special counsel presents the question of how a “norm” is defended or enforced.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

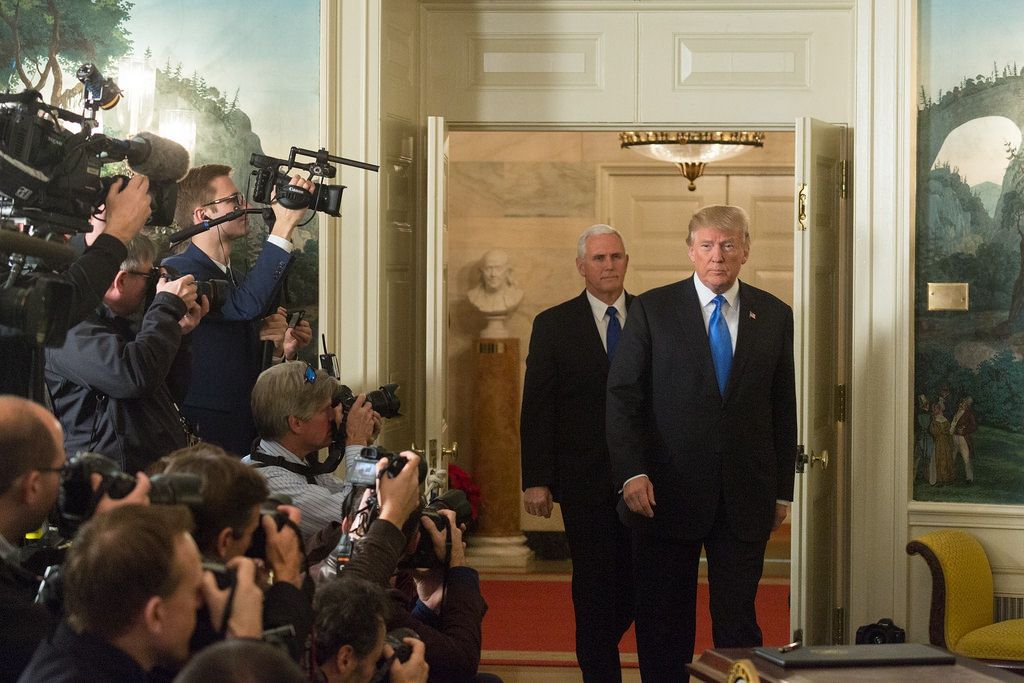

The possibility that the president will reject full cooperation with the special counsel presents the question of how a “norm” is defended or enforced. He has vacillated on his intention to testify, only to “walk it back.” Yesterday he turned in a similar performance in an impromptu appearance before reporters in the office of his Chief of Staff John Kelly. He said he would “love” to meet with Mueller and looked forward to the encounter. Then, perhaps realizing that he had gone too far, Trump amended and revised his remarks: “You know, again, it’s—I have to say—subject to my lawyers and all of that—but I would love to do it.” His personal counsel Ty Cobb clarified that, yes, while president would be “ready” to meet with the special counsel, he would be guided in the matter by “the advice of his personal counsel.”

So the question of cooperation is left open, as it was when only a few weeks ago, the president said only “we’ll see” about speaking with Mueller and suggested that it was “unlikely” that he would need to do so. A great deal is at stake in the answer. Presidents generally accept the obligation to support the course of law enforcement inquiries. They affirm in this way that they are not “above the law.” Should he refuse to cooperate with Robert Mueller, Trump will have gone where previous presidents, including Presidents Nixon and Clinton, would not go. While it is true that Nixon only produced documents, not personal testimony, and Clinton negotiated voluntary terms of cooperation in lieu of testifying pursuant to an independent counsel subpoena, each of them cooperated with investigations that entailed considerable personal legal risk.

What next? Some dystopian speculation might bring out the ways that the norm in question could suffer a hard and maybe fatal blow.

Trump does not, of course, have to submit to a personal interview: He can assert Fifth Amendment rights. He probably will not do so in this case but is more likely to rely instead on an attack on Mueller’s legitimacy fused with an assertion of his Article II authority to control his own Justice Department. The moment will have come when he can act on his frequently declared judgment that the investigation is a “hoax.” Already, supporters are reportedly urging him strongly to resist an interview with Mueller.

The president and his lawyers could time the confrontation with Mueller to coincide with a mounting Republican and allied media assault on alleged irregularities in the Justice Department. Reports of a Mueller request for an interview in the coming weeks now appear alongside reporting that congressional Republicans may be preparing over that same period to escalate their case against the Justice Department. With this backing, Trump would decline to cooperate. While there is nothing in any of these questions about the behavior of FBI personnel to raise questions about the integrity or merits of the special counsel’s investigation, the president and his legal team may seize the opportunity to confuse the issue.

Up to this point, commentaries about a looming Trump-Mueller conflict have largely speculated about the possibility and consequences of the president’s dismissal of Mueller. Trump could also put the burden on Mueller (or Rosenstein) by initiating an all-out attack on Mueller punctuated by his own refusal to participate. Would Mueller proceed, or would he—and perhaps the Deputy Attorney General—resign? Mueller could proceed without the president, deciding on prosecutions on the available evidence, but with the understanding that this course guarantees that the investigation will face a heightened and unending attack on its credibility. He could also issue a subpoena for the president’s testimony. Then Trump’s lawyers could prepare to contest that demand in court--or the special counsel’s last-ditch resort to compulsory process could precipitate his firing and be the last act of his office.

It is fair to say that this would be a damaging and potentially fateful turn of events for the Justice Department and for the administration of justice, all stemming from the president’s indifference toward the norm governing his conduct regarding federal law enforcement.

Public polling suggests that in this conflict, a fair share of the public may side with Trump. The most recent polling does show that an overwhelming majority now believes that Trump should give his testimony to the special counsel. But this question has been necessarily framed in the abstract: The president has not yet declined to give the interview, nor has he given his reasons with the orchestrated support of congressional, cable news and social media allies. Even in this poll, 75 percent of Republicans and 40 percent of independents surveyed doubt the integrity of the Mueller investigation, viewing it as “mainly an effort to discredit Trump’s presidency.” In polarized political environment, a demagogic president will have an audience for his case against the norm and he and his advisers could well believe that they can grow it. There is anecdotal data to supplement and round out the polling: Noah Rothman, reporting his experience on the radio show circuit, reports that the “grassroots is eating up the notion Trump is a victim of systemic corruption in law enforcement.”

None of the possibly worst outcomes are certain to come to pass. So far, members of his administration have submitted to interviews with the special counsel. Trump did not direct them otherwise. This history does not bind him, however; it gives him cover for his own rejection of cooperation, in the event that he chooses that path. He can argue that he swallowed his doubts as long as he could, overlooking offenses and provocations, but that eventually it became painfully clear to him that the investigation was so compromised that it could not be salvaged.

Congress could step in and defend the norm, availing itself of a range of tools. The most aggressive of these, the initiation of impeachment proceedings, is not the only course open to the legislative branch. Congress could also pass resolutions to express its objections, and in its various interactions with the executive branch, exact a penalty for the president’s conduct. It found a way, for example, to thwart Trump’s campaign to force the resignation of Attorney General Sessions.

But there is no reason to think that this Congress will come to the defense of the special counsel’s demand for access to testimony from this president. There was a time when, as Jack Goldsmith suggested in June of last year, it seemed that Congress could well rise to the occasion if Trump fired Mueller. There is now much less chance of this. Prominent congressional Republicans, encountering no audible objections from their caucuses, are escalating the attack on the Justice Department and the special counsel. Their ranks include Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley, who yesterday took to the Senate floor to speak of “the loss of faith in the ability” of the Justice Department and FBI “to do their jobs free of partisan political bias.” He has been joined in this offensive by Sen. Lindsey Graham, who has called for a second special counsel to investigate alleged Justice Department misconduct, and by a group of House Republicans led by House intelligence committee Chairman Devin Nunes.

The polling suggests this line of attack has made enough headway to assure that it will continue and alter the president and his advisers’ calculation of the risks and rewards of a clash with the special counsel. Some congressional Republicans may be unwilling to fully commit themselves at the moment—politicians typically prefer to bide their time so that they can better assess the risks—but for the most part, the Republican line against Mueller has been consistently hardening. By the close of last year, all talk of bipartisan legislation to protect the special counsel’s investigation had ended.

In the 2018 election year, facing discouraging political trends, Republicans may feel lashed for the moment to the president’s fortunes. To deal with the Mueller-Russia conflict, they may decide to make most of an unavoidably bad situation and turn it to their advantage. Their campaign message could well feature an all-in, “burn down the house” narrative about a corrupt establishment determined—as the president has often said—to reverse the 2016 presidential election outcome. The White House and its party would choose this plan of attack after considering the alternatives, and it may strike all concerned on the Trump side that the risks of cooperation are too high—and the political benefits of refusing it significant enough—to make this the politically smarter choice.

For the defense of the norm that the president is not above the law, the better part of the responsibility may lie with state and local community leadership and civil society institutions. Justice Department leadership may have to resign en masse in acts of individual and professional conscience. The national and local bar associations will have to be heard from. The question is whether there resides, outside government and the operation of what now passes for ordinary politics, the sources of needed moral leadership and principled argument. The president may be able to count on die-hard supporters, but they are not a majority, and the number can be whittled down still more. But it is far from a sure thing.

Meanwhile, this president may now be observing how he can disregard a norm and escape accountability. The White House press secretary, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, yesterday shrugged off an NBC report that the president asked deputy FBI director Andrew McCabe who he voted for in 2016. She said she did not know whether the president asked the question. She did not offer to find out. She volunteered no official support for the proposition that presidents should not press for this information from senior law enforcement officials. To her mind, the issue simply did not matter, and she suggested that she also was speaking for the American people: “I very seriously doubt that any person in America would list that as an issue they care about.”

Ms. Sanders has not jumped too far ahead of her boss. The president told reporters at the gathering in John Kelly’s office that he did not remember whether he asked McCabe about his 2016 vote. But he made clear his view that any such question would have been fine—“not a big deal,” and “very unimportant.”

The Chair of the Republican National Committee, Ronna McDaniel, also offered an opinion. Trump’s exchange with McCabe was “just a conversation,” no more than “getting to know somebody.” She “sometimes” asks this same question, she advised her interviewer. It followed for her, apparently, that because the president is her boss, the ultimate head of the party, he should be able to ask the same question in screening senior government law enforcement officials.

That may be the end of this episode and the beginning of a slow but steady deterioration of the norm. This is not precedent or a lesson that Donald Trump can rely on in considering how far he can go in denying cooperation to Mueller. But as he looks back on the first year—the organization of business interests, his attacks on federal law enforcement, his successful determination to withhold his tax returns, and other systematic challenges to governing norms—he may have reason to think that he can pull off this next one, too.