Trump’s Planned Counter-Report Is Fair Game for Congressional Testimony

The coming week may bring not just one but three reports on the Mueller investigation. Of principal interest, of course, is the original document by Robert Mueller. Then there is the redacted version of the report that Attorney General William Barr will release.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

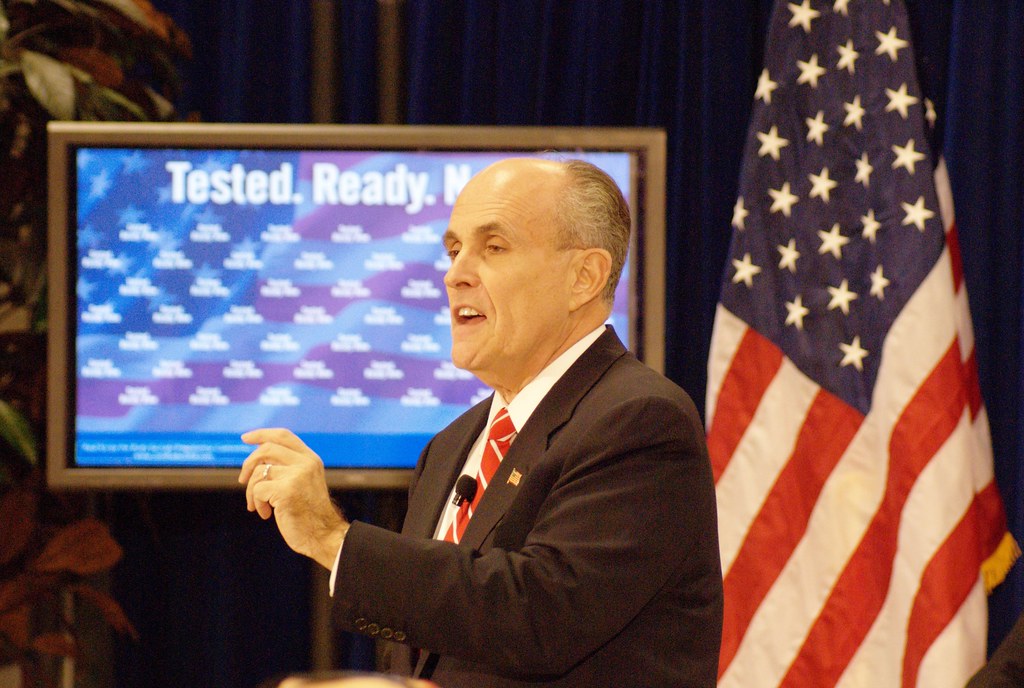

The coming week may bring not just one but three reports on the Mueller investigation. Of principal interest, of course, is the original document by Robert Mueller. Then there is the redacted version of the report that Attorney General William Barr will release. And a third report is apparently largely prepared and ready to go: Rudy Giuliani tells the Washington Examiner that the president’s lawyers have authored a “counter” to Mueller, focusing on the issue of the president’s involvement in obstruction of justice.

As a consequence of this maze of reporting, and with uncertainty about when the full and unredacted Mueller report will see the light of day, Congress has already acted to supplement the written record with personal, sworn testimony. Barr is set to testify about the report—both his original four-page summary and now the redacted version—before the House and Senate judiciary committees in the first days of May. Congress, or at least the House, will also want to hear from Mueller—and it eventually will, even if this testimony comes about only after the administration exhausts various defensive maneuvers. It is not clear, for example, whether the president will seek to invoke executive privilege on some theory to protect against or limit the Mueller testimony. But it is doubtful he will succeed, except perhaps in introducing delay and using it to build his political case.

With Barr and Mueller testifying, the president’s lawyers should also have to appear and answer questions under oath about their own document—if indeed that document is released. The counter-report, for this reason, would probably not be the public relations masterstroke that Giuliani may have in mind.

The president’s lawyers have apparently constructed a report setting forth factual claims for public consumption, and this counternarrative warrants testing. On what grounds will they assert that their version of events is more dependable than the official narratives that they intend to refute? Legitimate questions include the range of sources on which the president’s legal team relied for their claims: Whom did they interview, and what documentation was available to them? This information, including documents, should be made part of the public, congressional record.

The president and his lawyers might try to invoke attorney-client privilege to prevent such testimony. But both President Trump and his talkative lawyer Giuliani have little to sustain a claim of privilege.

The first problem they would face becomes immediately apparent from the nature of this counternarrative. It will not be a document prepared in anticipation of litigation, or for legal defense of the president. It will be crafted for political and public relations purposes—which is all the more indisputable now that the president will apparently be responding to a Mueller report that did not affirmatively conclude that the president violated any law, passing on any final judgment on the obstruction issue. Moreover, the attorney general has made the final determination that the department will not bring charges. The circumstances in which the counter-report may be released clearly do not support the position that it was developed or would be released for purposes of the president’s legal defense.

Even if considered on the merits apart from this context, the claim of attorney-client privilege would have to fail on these facts. The president has authorized his lawyers to put out a written statement of facts about his conduct as it bears on the issue of obstruction: According to Giuliani, it appears that the legal team has revised the original draft 140-page report, which dealt with both collusion and obstruction, to address primarily if not exclusively the latter. This disclosure, if it occurs, fatally undermines any claim of privilege. Any discussion of the collusion charge will have the same effect.

It will not help for the lawyers to insist that the counter-report discloses only facts, not client communications, and, therefore, that their communications with their client remain privileged. Because the facts arise from and expose those communications, their disclosure would be inconsistent with the claim of privilege. The law on this arises typically from circumstances very similar to these, when an institution releases the results of an internal investigation to the public. Disclosure even for self-serving purposes, where the lawyers pick and choose what to reveal, still constitutes a waiver. This privilege is always narrowly construed.

With this privilege out of the way, the president and his legal team would then be subject to congressional demands for a full explanation of all the bases for the factual assertions in their report. The lawyers might be able to protect interview notes containing mental impressions, but other information, such as the identity of those they interviewed and documents on which they relied, would be fair game.

It is worth noting that Congress has consistently refused to recognize attorney-client privilege when it is asserted and functions as an obstacle to the discharge of the legislature’s constitutional responsibilities in conducting oversight and developing legislation. Nonetheless, Congress does attempt to accommodate to some degree, when it can, the core interests in confidential attorney-client communications. But it would not be highly motivated to do so where, as here, a privilege claim is so flawed on its intrinsic merits.

There is another, larger principle at stake in holding the president to account for the counter-report. The president is already actively attempting to blur the lines between his private rights and public responsibilities in litigation over his purported right to “block” access to his Twitter account. It is similarly questionable for him to deploy his legal team to engage with Congress and the public over the Mueller report, both through the written counter-report and on cable news, and then retreat behind a claim of privilege to shield them from full accountability in the course of legislative oversight.

Congress will need to hear from Barr and Mueller about the reports, edited and full, for which the two are responsible. Rudy Giuliani is an entirely justified addition to the witness list.