Two Witness Testimony Rulings in the Military Commissions

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

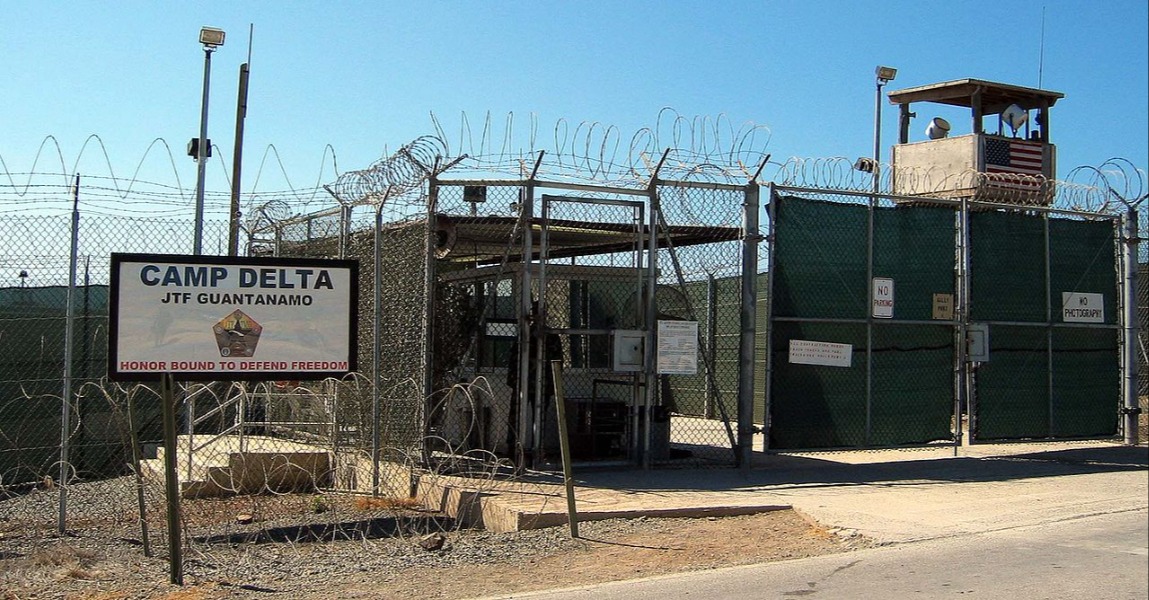

The sentencing hearing in the government’s military commissions case against Abd al Hadi al-Iraqi begins next week. Hadi, who arrived in Guantanamo Bay in April 2007, pleaded guilty in 2022 to charges associated with commanding insurgents who attacked U.S. allied forces in Afghanistan in 2003 and 2004. Specifically, Hadi pleaded guilty to attacking protected property and to treachery and conspiracy.

It took more than 15 years for Hadi’s case to end in a guilty plea, but the long road does not end there. Next comes sentencing, which also requires a huge amount of work in the commissions system, and much of that work relates to witnesses. In the civilian trial system, once the court reaches a decision, sentencing is generally a quick process. In the commissions, sentencing requires a whole other trial—which often includes the presentation of a substantial body of evidence. This is true whether the defendants agree to a guilty plea or not.

Another of the military commissions recently held sentencing hearings for two defendants, Mohammed Farik Bin Amin and Mohammed Nazir Bin Lep, who—like Hadi—had pleaded guilty to their decades-old crimes related to the October 2002 bombings in Bali, Indonesia. I was there “live” at the Fort Meade virtual viewing area—which live streams proceedings at the Guantanamo Bay military commissions—as two challenges related to sentencing and witness testimony facing the commission played out.

Judge Lt. Col. Wesley Braun made two rulings during Bin Amin and Bin Lep’s sentencing hearings related to “victim impact statements” that may indicate how witness testimony could be handled during sentencing hearings in Hadi’s case and in other commissions cases. In both rulings, Judge Braun ultimately approved the mode of witness testimony the government had requested. First, he allowed victims to read their statements from the witness stand instead of testifying by memory. Second, he permitted witnesses in the courtroom to read the statements of victims (including victims’ relatives or others affected) who were not able to physically attend the proceedings at Guantanamo Bay.

In the Hadi case, the government has not—up to this point—asked the judge for permission to have its witnesses read their testimony from the stand or read into evidence testimony from individuals not present at Guantanamo Bay, according to statements provided to Lawfare by Susie Hensler, lead counsel for Hadi. But Hensler noted that the victims have not yet testified; it is therefore possible that the government will request similar procedures as the government did in the Bali bombings case. (Lawfare reached out to the prosecution for comment but did not receive a response.)

The rulings from Judge Braun are not binding on other commissions, but given the dearth of cases in the commissions system, it is likely that if a similar situation were to arise in the Hadi case (which also involves a guilty plea), that commission would likely at least consider Judge Braun’s rulings on these issues.

Background on the Bali Bombings Case

The case against Bin Amin and Bin Lep stem from three bombings in Bali, Indonesia, that occurred on Oct. 12, 2002, and killed 202 individuals, most of whom were from Indonesia and Australia. The two men pleaded guilty in January to conspiring in the bombings.

According to the guilty plea agreements, Encep Nurjaman—also known as Hambali, the alleged mastermind behind the Bali bombings and a Guantanamo Bay detainee—arranged around June 2000 for Bin Amin and Bin Lep to travel from Malaysia to Afghanistan to train with al-Qaeda. (Hambali’s case was previously linked to those of Bin Amin and Bin Lep, but the two men were severed from Hambali’s case last year.) Bin Amin and Bin Lep stayed at an al-Qaeda guest house and completed approximately two months of al-Qaeda basic training. Later in the year, Bin Amin treated wounded al-Qaeda fighters at an al-Qaeda medical clinic near Kandahar, and Bin Lep fought on behalf of al-Qaeda against the Northern Alliance on the front lines near Kabul.

Near the end of 2001, Hambali organized a meeting between the two men and Osama bin Laden to discuss an al-Qaeda suicide operation against Americans. At that meeting, Bin Amin and Bin Lep “swore a personal oath of loyalty” to bin Laden and agreed to participate in the operation. Two other men also joined the meeting and planned to participate in the attack. The plan was canceled when one of the two other men who attended the meeting was arrested.

Around December 2001, the two men went to Thailand at Hambali’s direction. Between the end of 2001 and approximately August 2003—including before and after the Bali bombings—Bin Amin and Bin Lep helped Hambali avoid capture, and supported Hambali and al-Qaeda in other ways, according to their pleas. The two men helped Hambali “transfer money for operations, and obtain and store items such as fraudulent identification documents, weapons, and instructions on how to make bombs.”

A very brief timeline of the detention of Bin Amin and Bin Lep: U.S. authorities first took the two men into custody during an August 2003 joint U.S.-Thai intelligence operation. The CIA held them in black site prisons, where they were tortured—according to the defendants’ lawyers. The U.S. government transferred Bin Amin and Bin Lep to Guantanamo Bay in 2006. The Guantanamo Review Task Force slated the case against the two men and Hambali for prosecution in 2010. But 2010 came and went with no trial. In 2016, then-Chief Military Prosecutor Mark Martins and the State and Defense Department envoys for closing Guantanamo Bay traveled to Malaysia—where the two men are from—to discuss a deal to repatriate Bin Amin. The deal reportedly would have included Bin Amin’s agreement to plead guilty and testify against Bin Lep and Hambali. Were Bin Amin to testify and remain in U.S. custody for four additional years, he would be repatriated to Malaysia to serve out his sentence. But that deal, and a similar one the year prior, never came together.

The convening authority overseeing the case against Bin Amin and Bin Lep, Col. Jeffrey Wood, referred charges against them, along with Hambali, and convened the military commission on Jan. 21, 2021—about 18 years after the three men were captured. The announcement came two days after then-incoming Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin said that the Biden administration did “not intend to bring new detainees to the facility and [would] seek to close it,” leading a former Obama administration official who was familiar with the effort to close the facility to believe that the announcement had been “an attempt to jam the incoming administration.” The three men were arraigned in August 2021, before Bin Amin and Bin Lep were severed from the case against Hambali in August and October 2023, respectively. Bin Amin and Bin Lep then pleaded guilty on Jan. 16 to conspiring in the Bali bombings.

Witnesses Can Read Their Own Statements

During the sentencing proceedings, which began on Jan. 23, Judge Braun considered two issues (among others): whether victims could read their own statements instead of testifying from memory and whether victims could read statements from people who were affected by the Bali bombings but could not attend the proceedings.

The judge eventually decided to allow the government to bring in evidence through its preferred methods. On the surface, these rulings seem like “pro-government” ones. In a way, they are. But these rulings came after the defendants decided to cooperate with the government. They had pleaded guilty; the case at this point was still part of an adversarial process, but that process was perhaps less of a “dispute” than it was a collaborative effort to arrive at a resolution. The military commissions rules provide during the sentencing phase of cases for the government to make a case in aggravation and the defense to make a case in extenuation and mitigation, but the parties can work together as they see fit.

Judge Braun made initial decisions on these issues on Jan. 23. The government lawyer, Col. George Kraehe, stated his plan to have witnesses who were present at the hearing and who were impacted by the bombings read their own victim impact statements in addition to statements from other individuals who were also impacted but were not able to attend the proceedings. (Witnesses composed the statements in preparation for these sentencing proceedings.) The commission first addressed the issue of whether individuals could read their own statements.

The judge said that “generally speaking, when we talk about examination of witnesses, the strong, strong preference is that witnesses testify from memory,” noting that there are certain exceptions—including “prior statements” made by the witnesses. Col. Kraehe argued that preventing witnesses from reading their statements is almost tantamount to excluding those witnesses altogether because of the harm witnesses would suffer if they had to testify from memory. He said, “I think exercise of those rights [to participate in the proceedings] are only meaningful if they are construed in a way that limits further emotional or psychological impact on the witnesses.” The two lawyers for the defendants expressed their support for the victims reading their impact statements verbatim, after the judge asked for their positions. Following these exchanges, Judge Braun determined that witnesses could read their own written statements from the stand, despite the fact that “no party here has been able to squarely identify rules that expressly permit such an approach.”

Although Judge Braun did not precisely explain the reasoning underlying his decision, he appears—according to the rules he cited during his discussion of the issue—to have ruled primarily on the basis of two rules in the Military Commission Rules of Evidence and one rule that is part of the Regulation for Trial by Military Commission. The first, Rule 1001(b)(2), reads:

The trial counsel may present evidence as to any aggravating circumstances directly relating to or resulting from the offenses of which the accused has been found guilty. Evidence in aggravation includes, but is not limited to, evidence of financial, social, psychological, and medical impact on or cost to any person or entity who was the victim of an offense committed by the accused. In addition, evidence in aggravation may include evidence that the accused intentionally selected any victim or any property as the object of the offense because of the actual or perceived race, gender, color, religion, national origin, ethnicity, disability, or sexual orientation of any person or that any offense of which the accused has been convicted comprises a violation of the law of war.

This provision does not mention reading statements in particular, as opposed to testifying to “aggravating circumstances” by memory. However, the judge may have relied on this provision because it allows the prosecution to bring in the kind of evidence that would be presented by the witnesses through their written statements—related to the harm that the Bali bombings had on them. But just because the prosecution can bring in this evidence, why does that mean the victims can read their statements, rather than testifying to their experience from memory? The argument referenced above made by the government’s lawyer, Col. Kraehe, is critical here.

If the commission must permit the prosecution to “present evidence as to any aggravating circumstances” caused by the offenses to which the defendant has pleaded guilty, victims need to have the ability to testify to the harms they have suffered. And if, as Kraehe argues, that ability to testify is guaranteed only if witnesses are able to deliver their testimony in a fashion that “limits further emotional or psychological impact,” then perhaps the judge believed that permitting witnesses to read their statements was the only appropriate way to accommodate witnesses. If that were the case, it would seem that permitting witnesses to read their statements verbatim may be required under Rule 1001(b)(2). It’s also worth noting that the judge was aware that defense counsel agreed before the witnesses testified not to cross-examine the government’s witnesses—meaning that if Judge Braun permitted witnesses to read their statements, that would allow their testimony to come in almost fully in this manner. (Judge Braun made clear, though, that cross-examination was still available to the defense.)

The second rule, 16(d)(13) from the Regulation for Trial by Military Commission, mirrors the first. It states, “[T]he following shall be provided by trial counsel or designee to victims and witnesses: … Notification to victims of the opportunity to present to the court at sentencing, in compliance with applicable law and regulations, a statement of the impact of the crime on the victim, including financial, social, psychological, and physical harm suffered by the victim.” This rule provides for the opportunity of victims to testify to evidence of the “financial, social, psychological, and physical” harm they have suffered from the crime at issue, whereas the above rule provides for the opportunity of the government’s lawyer to present evidence. (Individuals with close relationships to those harmed by the bombings are considered victims themselves.) The nature of the evidence described is essentially identical.

The third rule, Rule 611, gives the judge discretion to “exercise reasonable control over the mode and order of interrogating witnesses and presenting evidence so as to (1) make the interrogation and presentation effective for the ascertainment of the truth; (2) avoid needless consumption of time; and (3) protect witnesses from harassment or undue embarrassment.” This rule appears to provide judges with general authority to make process-related decisions about the trial. It is also very possible that Judge Braun believed allowing the witnesses to read their statements would be more likely to bring out the truth or prevent the witnesses from experiencing feelings of harassment or embarrassment. This last reason, related to preventing harassment and embarrassment, is very similar to the argument made by the government’s lawyer.

Considering these rules, in addition to “the position of the parties articulated on the record, the nature of the evidence involved, and the availability of the proponent to be available for cross-examination,” the judge determined that the witnesses could read their written statements. That was the first ruling, and it was final.

Witnesses Can Read Third-Party Statements

But as Judge Braun accepted one of the government’s requests, he initially rejected another. When Judge Braun ruled from the bench on Jan. 23, he said he would not allow witnesses to read statements from individuals who could not be in court, despite no objection to this form of testimony from defense counsel. The reason, he said, was that the individuals who wrote those statements would not be open to cross-examination or questioning by the commission and that those reading the statements would not have “sufficient personal knowledge” of the statements. Judge Braun added that permitting those statements to come in through others would not be consistent with the Military Commission Rules of Evidence, specifically Rule 602, which requires that a “witness may not testify to a matter unless evidence is introduced sufficient to support a finding that the witness has personal knowledge of the matter.” The third-party statements would still be admitted as evidence and would be available for the jury’s consideration, but witnesses present could not read them aloud in court.

That was Judge Braun’s initial ruling on the question, but the commission would revisit it twice over the next two days.

Discussion of third-party statements began the next day, on Jan. 24, when the judge reminded the government’s lawyer of his ruling from the day before (which rejected the government’s request to have witnesses read other individuals’ statements into evidence). Judge Braun expressed concern that the government was at least approaching the line of discussing third-party statements in too much detail, even if the witnesses were not reading the statements verbatim.

Bin Lep’s lawyer, Brian Bouffard, then jumped in and offered a solution to allow the third-party testimony to be read into evidence: The defense could call the government’s three witnesses who would read third-party statements as witnesses for the defense—under relaxed rules, which the defense has the authority to call upon. The government clarified that it had no responsibility for making this proposal after Judge Braun’s initial ruling; it was fully the work of the defense.

The judge noted that under the Military Commission Rules of Evidence, Rule 1001 the defense does have the ability to relax the rules and that “there’s case law precedent permitting a similar relaxing of the rules … for the government’s case in any rebuttal matters.” Bouffard said that relaxing hearsay and authenticity rules in particular might be helpful. The judge did not make a decision at that moment and said that he would allow the government to continue presenting its case and wait to decide the issue until the defense raised it when it presented its case. Judge Braun also clarified, in response to a question from Bin Amin’s lawyer, Christine Funk, that the defense cannot relax the rules in the government’s presentation of its sentencing case; it has to wait for the presentation of its own case to do so.

Funk opened the proceedings on Jan. 25 with a request to relax the rules of evidence and recall one of the government’s witnesses to read the third-party statement into the record, as Bouffard previewed the day before. The judge granted the request to “relax the rules” under Rule 1001 “for purposes of foundation, authentication, and reliability” and allowed the defense to call the government’s witness.

Although Judge Braun did not provide any further explanation for his ruling, he almost certainly relied on Rule 1001(c)(3), which reads: “The military judge may, with respect to matters in extenuation or mitigation or both, relax the rules of evidence. This may include admitting letters, affidavits, and other writings of similar authenticity and reliability.” This provision enables the judge to permit the defense to work around rules that otherwise might prevent certain evidence from entering the record, or—as was the case here—work around rules that would prevent evidence from entering the record in a particular way. Hearsay and authenticity appeared to be the primary obstacles that would have prevented the government’s witnesses from reading statements from those not present at Guantanamo Bay.

The commissions’ hearsay and authenticity rules provide judges, even outside of the context of relaxed rules, with a significant amount of agency to determine whether relevant evidence is sufficiently probative and reliable under the circumstances to advance the commissions’ aims of justice. However, it appears that without defense counsel’s offer to bring the government’s witnesses as part of the defense case, Judge Braun likely would not have allowed government witnesses to read statements from others into evidence because of the hearsay and authenticity obstacles. But with the rules relaxed at the defense’s request, defense counsel were able to call all three of the remaining government witnesses to read the victim impact statements written by others who could not attend the proceedings at Guantanamo Bay.

Will This Matter in Future Cases?

Whether these two rulings from Judge Braun will matter in Hadi’s sentencing hearing or in future military commissions sentencing hearings depends heavily on the context of the case at issue and on both sides’ strategic and procedural decisions. However, Judge Braun’s rulings could indeed serve as meaningful precedent in other commissions cases with similar procedural postures, like Hadi’s: where the defendant has pleaded guilty, and the government and defense are working cooperatively to resolve sentencing issues. In fact, Hensler, Hadi’s lawyer, told me that the defense has expressed a willingness to work with the government to bring in victim statements through collaborative procedures.

But under different circumstances, the effect of the rulings is far less clear.

Without the cooperation and assistance of the defense in bringing in the government’s witness testimony, it is not clear that Judge Braun would have reached either of the decisions that he ultimately did. If the defense had objected to witnesses reading their written statements, the judge’s calculus could have changed. And if the defense had not offered to relax the rules of evidence and bring the government’s witnesses as part of the defense case, that third-party testimony almost certainly would not have been read aloud.

But even if the same kind of cooperation were to exist in another case, strategic decisions by the government could also preclude Judge Braun’s rulings from having an effect. On the ruling that witnesses can read their own statements, if the government for some reason prefers victims testify by memory instead of reading statements, it won’t apply. And the ruling that witnesses can read statements from third parties would not apply if the government does not wish to bring in testimony from any individual who is unable to testify in person.

Judge Braun’s rulings could matter in the Hadi case, or they could not. They could also matter in a different case. It’s not clear. But the relatively small number of cases in the military commissions system means that many of these kinds of procedural questions have not yet been resolved. When judges rule on them, it’s worth noting.