U.S. Sanctions Relief for Syria Is an Important Start, but Not Enough

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The unexpected fall of President Bashar al-Assad and with it the end of the Assad dynasty prompted jubilation from many long-suffering Syrian people, but they face sobering challenges as they try to rebuild their society. A central problem remains the enormous web of overlapping sanctions that countries opposed to the regime and its abuses imposed during the civil war.

The United States has been the primary architect of many of these sanctions. Over the years, the United States and its allies have shown few signs of readiness to make lasting changes to their sanctions regimes, but on Jan. 6, the United States took a promising step by easing some restrictions. The U.S. Treasury issued General License 24, allowing certain transactions with the Syrian government, including energy sales. The Biden White House also waived a foreign assistance restriction, allowing U.S. aid to flow to a handful of countries if they assist Syria. President Trump has so far left these policies in place, and his secretary of state expressed interest in “exploring” a relationship with Damascus to advance U.S. interests. But the Trump administration must offer bolder reforms if it wants to prevent the new Syria from descending into chaos.

Crucial Steps

The general license will last for six months and is intended to unblock restrictions on support to essential services and key governance functions of the Syrian state. Specifically, it authorizes transactions with the government in Syria as well as energy-related business in the country. It also permits transactions necessary for the processing of noncommercial, personal remittances to Syria, including through the country’s central bank. Such gifts to friends and family have been allowed since 2015, but the license slightly expands the scope of the permission.

There is a lot to celebrate in General License 24. Relaxing sanctions on Syria’s current caretaker government, a regime that is untested and led by an Islamist group once linked to al-Qaeda, is a risky move in Washington, where politicians across the spectrum have called for a cautious approach. Offering relief so quickly—hardly a month since Assad’s ouster—is unusual and required a strong stomach for political risk. By contrast, the United States waited six months to offer major sanctions relief to Afghanistan after the Taliban takeover of the country, during which time the country plunged into a humanitarian crisis so severe that the United Nations called it the worst in the world. Perhaps the Biden administration felt that the license went as far as possible, in case its successor disapproved of measures it perceived as rewarding Syria’s de facto leaders.

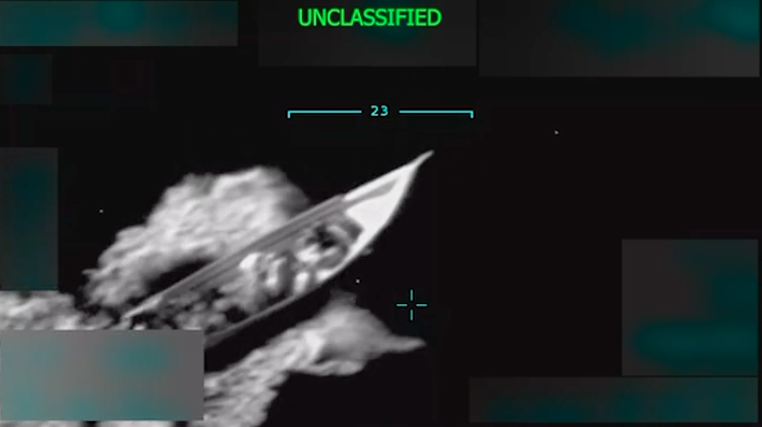

In Syria, the new general license will help to keep the lights on, quite literally. The day after the Treasury Department announced the measure, Turkey said it would send an electricity-generating ship to boost energy supplies for Syrians, most of whom receive only a few hours of power a day. Soon after, Qatar announced it would supply 200 megawatts of electricity to Syria. Whether or not Turkey or Qatar would have provided the electricity in the absence of the license, it certainly eases the path for a range of actors to provide energy support to the country. Prior to the fall of the Assad regime, the Syrian government had relied on Iran and Russia for its energy resources. Without this measure, Syria might have been forced to call on them again.

The license also sets an example for European and other governments that have yet to issue their own exemptions for their heavy sanctions on Syria. It could give them the impetus—or cover—they need to issue similar licenses or perhaps even provide more significant sanctions relief to suffering Syrians. It could also set a precedent for further U.S. sanctions reforms under the Trump administration, although it is not clear whether Trump will be in favor of such policies.

In its final hours, the Biden administration also issued a waiver to the Foreign Assistance Act, which prohibits the United States from providing assistance to countries that aid terrorist states. Given that the United States designates Syria as a state sponsor of terrorism, the legislation blocks countries that give aid to Damascus from receiving aid from Washington. The Biden administration’s action allows American assistance to flow to specified countries—Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and Ukraine—if they support Syria. The waiver thus removes a hurdle for Washington’s partners that want to promote Syrian recovery. It is not clear, however, what the impact of the reform will be. Some of the countries to which the waiver applies had started to offer support to Damascus right after Assad’s ouster, when no such waiver existed, and others are not traditional recipients of U.S. development assistance (although several receive military support).

The Harshest Impacts of Sanctions Continue

Even with the general license and the foreign assistance waiver in place, intensive sanctions continue to choke Syria’s economy and complicate the provision of aid to the country. For this reason, it was somewhat ironic when then-Treasury Deputy Secretary Wally Adeyemo highlighted the unique opportunity “for Syria and its people to rebuild” when he announced the general license—because that is something the license will not quite allow. Even with the new license, a near-total embargo remains on the country as a result of U.S. restrictions—an effect amplified by overlapping restrictions from European and other countries. U.S. sanctions still block entire sectors of Syria’s economy, forbid new investment in Syria, and prohibit trade with Syrian companies.

The fact that the license is time-bound and is scheduled to last only six months is concerning, even if that horizon was determined out of consideration for the coming change in administration. That’s hardly enough time for humanitarians, businesses, or other outside actors to establish a meaningful presence in Syria. By the time they launch their operations, the license—absent renewal—may have expired. They will likely be deterred anyway by uncertainty about the future. Such problems with expiry dates on licenses have occurred before. After the 2023 Syrian earthquake, the Treasury Department issued a short-term license for disaster relief, but humanitarian organizations barely got started rebuilding the critical infrastructure the earthquake had destroyed by the time the license expired. Adding to these problems, general licenses are easily revocable; this one could be removed by the Trump administration with the flick of a pen.

To make matters worse, the United States continues to designate Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the biggest group of victorious rebels who now make up the country’s de facto leadership, as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO). The listing makes any dealings with the group legally radioactive because it outlaws providing them “material support,” a broad term that goes beyond money and includes training, support, and assistance. Penalties for those who provide material support can be in the hundreds of millions of dollars and decades in jail. The listing remains even though the United States has removed the $10 million bounty on the HTS leader’s head, and many U.S. and other high-level visitors have streamed into Damascus to meet him.

The license offers a lifeline, but it’s nowhere near enough to clear the obstacles that sanctions pose to Syria’s recovery. It will help with maintaining basic services, not economic renewal. Washington remains silent about allowing new investment in Syria, which sanctions still prohibit. It also has not removed sanctions on Syria’s central bank, the nerve center of any modern financial system, meaning that the economy remains paralyzed. And while the foreign assistance waiver lets a handful of countries aid Syria, the U.S. government has failed so far to end restrictions on help for Syria from international financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. The White House has not removed Syria’s state sponsor of terrorism designation, one of the most severe penalties in Washington’s economic arsenal, and in December, Congress extended the Caesar Act, legislation responding to the Assad regime’s atrocities that imposes some of the most restrictive of all sanctions on the country. Washington has yet to provide Syria’s de facto authorities with a road map and conditions for how to get out from under this elaborate regime.

While the license may allow Syria to scrape by, it will not enable the resumption of normal business activity, international trade, and development assistance that will be required to end Syria’s isolation. Cut off from the world, Syria’s prospects remain bleak. Rising poverty could worsen the humanitarian crisis, which already affects some 33 million people in Syria and the region. Within the country, needs have spiraled in recent weeks, with the price of bread soaring and electricity and water access scarce.

The Contradictions of Sanctions

The license also does not counteract the effects of the HTS designation as an FTO. Treasury licenses are issued under laws that do not cover restrictions related to FTOs, which fall under a completely different set of rules. In other words, the license does not excuse anyone from complying with FTO-linked material support laws. As long as the FTO designation remains in place and HTS is de facto controlling Syria’s government, businesses and nongovernmental organizations may fear that engagement with the new authorities could get them in hot water—even if their activities do not technically run afoul of U.S. laws. Such fears may cause humanitarians, and the financial institutions and private-sector suppliers that facilitate their work, to avoid working in Syria (or steer clear of conducting certain activities there). Such humanitarian “derisking” was an issue in northwestern Syria, which HTS has controlled since 2017. It now threatens the whole country.

The general license also does not apply to restrictions by other U.S. agencies, such as the Department of Commerce, which maintains intensive export controls on Syria. With narrow exceptions, U.S. export controls prohibit the export of virtually everything other than food and basic medicine to Syria—including energy. This means that the very same activities allowed by one arm of the U.S. government through the license are prohibited by another.

It is possible to get permission from the Department of Commerce to export otherwise prohibited goods. However, getting permission requires a time- and resource-intensive application process for a specific license, which the department grants on a case-by-case basis after a consideration period that can last up to two months. Commerce restrictions pose an enormous challenge for humanitarian organizations working in Syria, which need licenses to run everything from their computer programs to their demining and water projects.

This confusing picture baffles even the most seasoned diplomats and sanctions experts, who throw up their hands in exasperation after poring over the convoluted regulations. They are not alone. The complicated regulatory environment means that businesses often choose to avoid working in a place as heavily sanctioned as Syria rather than stomach the risk, compliance costs, and time it takes to navigate the legal labyrinth required to work in such a place—even if, technically, their work is allowed.

Given the complexity and comprehensiveness of the Syria sanctions regime, until there is major sanctions reform—not just carving out partial exemptions—Syria has no realistic path toward economic regeneration and humanitarian recovery. Meanwhile, the costs are mounting for the Syrian people, who deserve to live with dignity. The interests of the United States, which does not want deeper instability in Syria and the region, also hang in the balance.

A Unique Opportunity

Fortunately, Washington has all the tools it needs to do better. After all, the United States imposed the restrictions on Syria; it can remove them, too. Washington has a unique opportunity to use sanctions as they were intended: as a tool of leverage to encourage better behavior. The Trump administration should seize the opportunity to negotiate a meaningful arrangement with Syria’s interim leaders—one that secures U.S. interests while holding the ex-rebels accountable for governance choices that foster peace, security, and prosperity in the country.

As a priority, Washington should craft clear, realistic, and time-bound demands for Syria’s caretaker leaders in exchange for full relief from sanctions on HTS and the country writ large. Unraveling the complex web of U.S. sanctions on Syria will take time, and would have to be coordinated with other countries, but Syrians should not have to keep paying enormous costs for the former regime’s crimes. Concerns about the risk of backsliding should be tempered by the fact that sanctions, as well as a range of other punitive measures, can be reimposed if Syria’s leaders deviate from their commitments.

In the meantime, to curb the drivers of Syria’s humanitarian crisis, Washington should take the following actions, quickly. The Trump administration should immediately and without conditions remove barriers on critical sectors, such as the central bank. Also, the Treasury Department should take immediate steps to extend General License 24 indefinitely and broaden it to allow for commercial and economic activity. Clarification that Syria’s governing institutions are distinct from designated entities would also be helpful, as it was with the previous license for Afghanistan where a designated terrorist group, the Taliban, also controls the government. Additionally, the Department of Commerce should issue a license exception that mirrors the Treasury Department’s authorizations, or at the very least expedite license processing as it did after the 2023 earthquake. Such measures should be seen not as undermining the Syria sanctions regime but, rather, as calibrating its effects so that they target the Assad regime’s abuses rather than vulnerable Syrian civilians.

Recent sanctions reforms represent important progress, but at this unprecedented moment in Syria’s history, they are only a fraction of what is needed to enable true recovery. In the meantime, the existing restrictions are worsening an already dire humanitarian crisis and pushing Syria further toward the brink. Washington should take advantage of the opportunity to shape Syria’s future for the better and remove the obstacles it has placed in its path. Inaction could place a millstone around Syria’s neck that drags it back toward chaos and suffering, but bold and decisive steps can advance Washington’s interests and help unlock a brighter future for the Syrian people.