On the Unconstitutionality of Iran’s Current Constitution

The lesser known story of a silent counter-revolution in 1989 in Iran that led to the creation of Iran’s constitution today—and why this constitution is unconstitutional.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

“Iran’s constitution is unconstitutional!” It was a cold November day in 1978 when Ruhollah Khomeini, soon to be the leader of the 1979 revolution in Iran and Iran’s first supreme leader, said these words to his audience in Paris. This wasn’t the first time. He had been making similar arguments for the prior 15 years in major declarations and speeches.

The gist of Khomeini’s argument was that Iran’s 1906 constitution, written subsequent to the 1906 Constitutional Revolution, didn’t have a provision on how to amend the constitution. Again and again, Khomeini argued that in the absence of such a constitutional provision, the 1925 Constituent Assembly—which amended the constitution, deposed the Qajar dynasty, and replaced it with the Pahlavi dynasty—lacked legality and legitimacy. The issue was that in 1921, Reza Khan, commander of the Persian Cossack Brigade, staged a coup d’état and subsequently induced the parliament to unconstitutionally proclaim itself a constituent assembly and proclaim Reza Khan as the king of Pahlavi. The revolutionaries rightly maintained that these changes were simply against the text of the constitution.

Even after these changes in 1925, the 1906 constitution still didn’t have a provision for how it could be amended. In 1949, the Shah of Iran, son of Reza Khan, unilaterally issued a decree ordering the government to amend the constitution. These changes consolidated the power in the person of the Shah and added a provision that stated procedures for future amendments. The Shah of Iran used this new mechanism to further augment his powers. Khomeini insisted in his speeches and declarations that, in the absence of a constituent assembly, all of these changes were illegal and against the text of the constitution. With the constitution being unconstitutional, the argument ran, all laws lacked legality, and the entire dynasty was unconstitutional. Eroding the legality and legitimacy of the regime, Khomeini slowly substituted the divine rights of the kings in a constitutional monarchy with his theory of sovereignty, Velâyat-e Faqih, or the sovereignty of God through the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist. Uprising against the Shah and the constitutional monarchy, he told people, wasn’t just legitimate—it was legal.

Revolutionaries throughout history have, similar to Khomeini, relied heavily on claims of the unconstitutionality of existing government structures and combined this critique with a new rationale of legitimacy to engender public support for change. In many cases, a new perspective on legitimacy involved a new theory of sovereignty, not only challenging the legitimacy of the Ancien Régime along with the claims of unconstitutionality but also serving as the governing principle of the future state. For example, on Feb. 7, 1688, the Lords and Commons of England, in the Convention of 1689, had declared that “King James the Second ... [had] endeavored to subvert the constitution of the kingdom [and], by breaking the original contract between king and people, ... violated the fundamental laws.” This legal challenge was coupled with the growing theory of popular sovereignty. According to historian Steve Pincus, “for Opposition Whigs, the popular resistance of the revolutionaries in 1688–89 was lawful because they believed deeply in the principle of popular sovereignty.” These principles applied by revolutionaries were enunciated more systematically in the works of Algernon Sidney and John Locke. The Founding Fathers of the U.S. similarly relied heavily on claims of unconstitutionality. As historian Charles Howard McIlwain states, “[T]he Americans stoutly insisted during the whole of their contest with Parliament to the summer of 1776 that their resistance was a constitutional resistance to unconstitutional acts.” Here, too, the revolutionaries combined arguments of unconstitutionality with a subsequent theory of sovereignty.

Many successful revolutionaries have combined claims of unconstitutionality with a new theory of sovereignty to successfully challenge the existing system because sovereignty is not just “the author and source of law.” It is also its destroyer. Not only does it have the power to bind the clauses, articles, and sections of the constitution together—in the same breath, it also creates, justifies, and commands obedience. It has the power to unravel and annul the constitution. In short, it has the ultimate power to justify disobedience and revolutions. The story of Iran is no exception. And Khomeini knew this.

Today, the Iranian state apparatus claims a monopoly over the 1979 revolution and the legitimacy and legality that stem from it. This has left many activists who are hoping for change, inside and outside Iran, to regret the 1979 revolution itself. But this is a trap set by the narrative and propaganda of the Iranian state. Instead of buying into this narrative, Iranian activists hoping for change might take a page from Khomeini’s book and criticize the post-1989 apparatus of the Iranian regime as a departure from the principles of the 1979 constitution and revolution. The focus should not be on the 1979 revolution but on the silent counter-revolution in 1989—the focus should be on how the current constitution of Iran is unconstitutional.

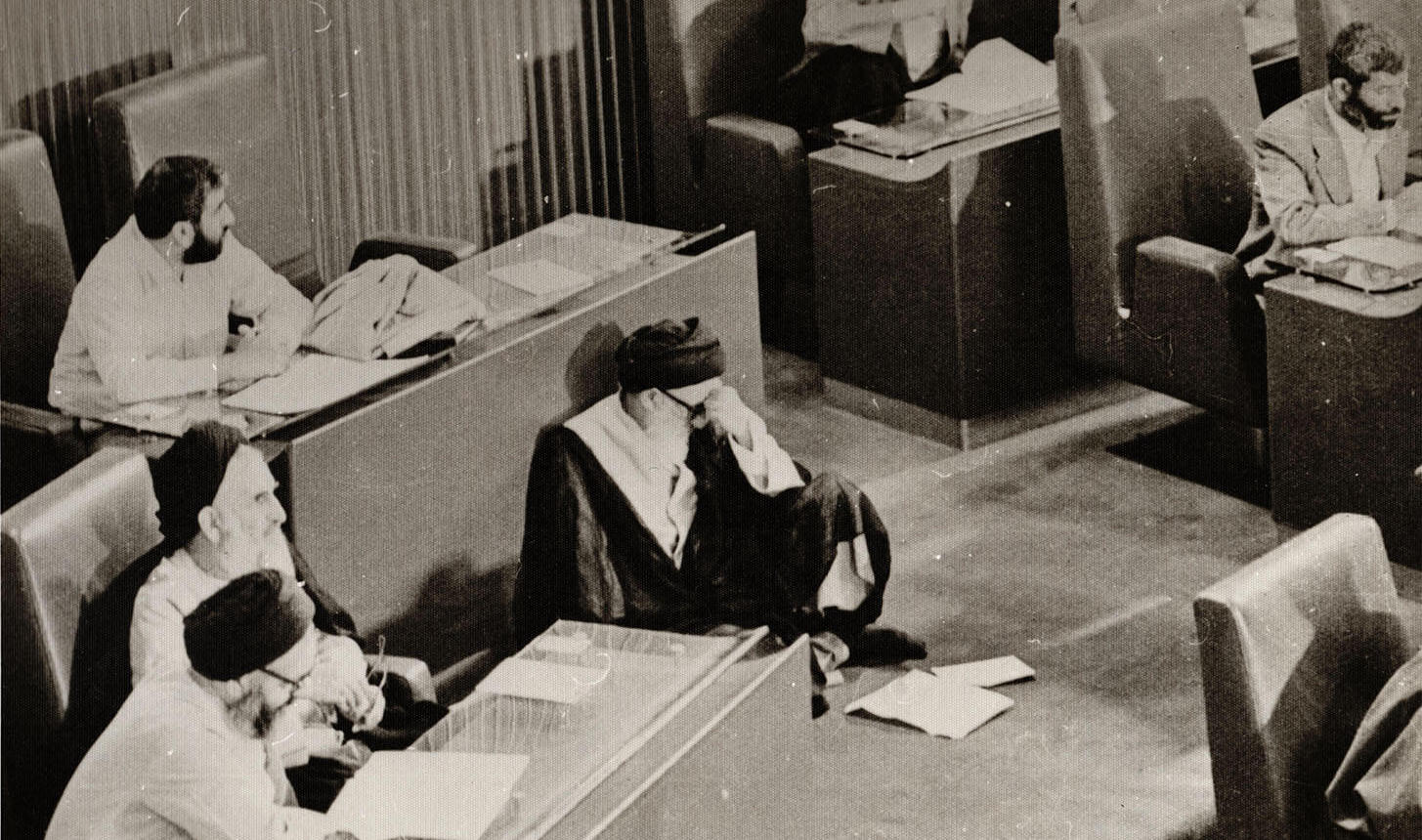

Iran’s 1979 Constitution

In 1979, after the Shah of Iran fled the country and following a subsequent referendum in which the super majority of the people stated they wanted an Islamic Republic (the details for which would be determined later), elections were held to elect representatives to form a constitutional assembly to draft a new constitution. The initial plan was to have a large assembly. But Khomeini contended that deliberation during the constitution-making process in a large assembly would endanger establishing Islam. This insistence on a small council with just 73 members ensured that only one or two candidates with a mere plurality of votes from each province were elected. The size of the assembly and the procedural rules guaranteed a pro-Khomeini constitutional assembly. The turnout on election day was low, just 51.7 percent of voters. Consequently, 76 percent of the members of the assembly ended up being clerics. Still, one woman was elected, and religious minorities—Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians—had representation. During the debates, Mahmoud Taleghani, an influential and popular cleric—one of the leaders of the revolution and a powerful member of the assembly who opposed Khomeini’s conception of sovereignty and advocated a republic based on popular sovereignty—made a passionate speech on the dangers of a theocratic tyranny in Friday Prayer attended by thousands. He died in a mysterious way just two days before the historic vote on the article regarding the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist. With the sudden death of the leader of the opposition, the constitution was written with few obstacles and put to a referendum. So far, despite all the irregularities and questions, the constitution met a minimum test of revolutionary legitimacy and constitutionalism. Khomeini had ensured his criticism of the Ancien Régime would not apply to this new system.

This story is well known to Iranians. And for the past four decades, the Iranian state apparatus had relied on this narrative to claim legality and legitimacy, both domestically and internationally. But a lesser known fact is that the constitution of 1979 is not the constitution governing the country today. The fact that only a few people know this is no surprise. While being one of the most prominent countries in the global news, Iran remains veiled in secrecy.

The constitution of 1979 had given immense powers to Khomeini. But the constitution still had many republican features. The rule of clerics was not absolute. Above all, one power was denied: the power to amend and change the constitution. Similar to the 1906 constitution, the members of the Assembly of Experts couldn’t agree on an amendment procedure. In the original draft, there was an article on how to amend the constitution. Article 148 of the draft stated that “[w]henever a majority of members of parliament or the president with the advice of cabinet shall deem it necessary, [they] shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, [and] … when approved by three fourths of members of the parliament, it shall be put to referendum.” Some members of the constituent assembly proposed changing this article to the following:

The Parliament, whenever it shall deem amending or changing certain articles of the constitution necessary, can, with the approval of 2/3 of its members and the Supreme Leader, call an Assembly of Experts (Constitutional Convention). The Assembly of Experts shall be composed of 70 legal and religious scholars who are chosen by the people. Its powers are limited to amending the specified article or articles, and the decisions have to be approved by 2/3 of its members[.]

But the Islamists and republican factions of the assembly clashed and couldn’t agree on the details. Thus, the question of how to amend the constitution was left unaddressed.

The final understanding was that in the absence of a clause clearly stating how to amend the constitution, whenever amending the constitution was required, the only conceivable way of doing so was to repeat the 1979 procedure. That is, Iran would have to first have a referendum on whether people would want to amend the constitution under Article 59 and then hold a constitutional assembly election, see the formation of another constitutional assembly, and submit the final result to the people via a referendum. Ten years later, on his deathbed, Khomeini decided otherwise. This time, Khomeini would do the same unconstitutional acts that he had criticized the former Shah of Iran for doing in 1949.

The Silent Coup of 1989 and the New Constitution

Forty days before his death, Khomeini issued a decree that was clearly outside his legal and constitutional powers. He simply repeated the unconstitutional acts of the Shah of Iran in 1949. Khomeini’s unconstitutional decree created a council of 25 men. Of these, 20 were directly appointed by him, and the other five were appointed by the legislature. Twenty-two members of this council were conservative clerics. Not a single woman, representative of religious minorities, or even political party was included. An unconstitutional, illegal, and unrepresentative council was formed in 1989. This council rewrote one-third of the constitution, and with that the revolution of 1979, under the guise of reform. Simply put, if the 1979 constitution created an Islamic Republic, the 1989 unconstitutional revision erased the republican parts of the constitution.

Here are a few of the many changes this unelected and unconstitutional council made: The Guardianship of the Supreme Leader was made absolute. The requirement that the Supreme Leader should be accepted by the majority of the people was removed. The judicial branch, media, referendum, and revision of the constitution were left under the full and unchecked control of the Supreme Leader. Under the 1979 constitution, all of these institutions were independent from the Supreme Leader. The Supreme Leader was made the arbiter between the three branches of government. The system was changed from semipresidential to presidential. Representation of religious minorities was suppressed. The National Assembly became the Islamic Consultative Assembly. The unconstitutional council even considered giving the Supreme Leader the power to annul the parliament. But, faced with the opposition of 177 members of parliament, the council rescinded this proposal.

Most importantly, the conditions for becoming the Supreme Leader were altered to match the credentials of Ali Khamenei. According to the 1979 constitution, only a Mujtahid (a person accepted as an original authority in Islamic law) could become a Supreme Leader, and Ali Khamenei was not a Mujtahid at the time. Finally, the new draft made the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist and the Islamic character of the political system unalterable. Still, the silent counter-revolution against the republican character of the 1979 constitution had one more obstacle. Article 59 of the 1979 constitution required that any request for direct recourse to public opinion, or referendum, had to be approved by two-thirds of the members of the then National Assembly. The council ignored the provision, conveniently adding the following clause in the new draft (which is now Article 177 of the current constitution): “The provisions of Article 59 of the Constitution shall not apply to the referendum for the ‘Revision of the Constitution.’”

Anticipating the imminent death of Khomeini, the decree issued by him gave the council a maximum of two months to revise the constitution. The council was in a rush to finish everything before his death. But, Khomeini passed away just 40 days after issuing the decree, before the council was able to finish revising the constitution and to complete its silent coup. This deepened the crisis of legality and legitimacy because, according to the constitution still in force, Ali Khamenei, not being a Mujtahid, could not become the new Supreme Leader. He simply lacked the legal credentials explicitly required by the constitution. He neither had the approval of the majority of the people per Article 5 nor was a Mujtahid per Article 107 and Article 109. In the face of all of this, the leaders of the silent coup decided to pretend the draft version of the constitution written unconstitutionally by the council was already in force. Then, despite protests, Ali Khamenei, who lacked the qualifications according to the 1979 constitution, was illegally and unconstitutionally elected by the Assembly of Experts for Leadership as the new Supreme Leader. Ali Khamenei then conveniently put the new draft to an unconstitutional referendum. It was an unconstitutional referendum because Article 59 of the 1979 constitution required referendums to be approved by two-thirds of the members of the National Assembly. No such approval was obtained. Thus, an unelected unconstitutional council rewrote the constitution, and an unconstitutionally chosen Supreme Leader put the draft to an unconstitutional referendum. And, voila, the counter-revolution was complete.

But like C.J. Box said of every crime, “[S]omething is always left behind.” The text of the constitution bears mute witness against this counter-revolution. Take a look at Iran’s constitution. The last paragraph of its long preamble states: “The Assembly of Experts, composed of representatives of the people, completed its task of framing the Constitution, on the basis of the draft proposed by the government as well as all the proposals received from different groups of the people, in one hundred and seventy-five articles arranged in twelve chapters” (emphasis added). Now, check the last article of the constitution. The constitution contains 177 articles, arranged in 14 chapters.

Why Does This Matter?

Every single mass movement in Iran since 1979 has struggled with the state’s claims of legality and legitimacy. Every year, in February, the Iranian government celebrates the anniversary of the revolution and constitutional referendum of 1979. According to the Ministry of the Interior of the Islamic Republic of Iran, which is in charge of performing, supervising, and reporting elections, policing, and other responsibilities related to an interior ministry, “More than 99.5% of the Nation of Iran said YES to the Constitution!!” Every channel of state media repeats this every day for at least 10 days during the long celebrations. Nothing is said about the turnout nor about the 1989 silent counter-revolution. Today, few Iranians even know that the constitution was fundamentally altered in 1989 in an unconstitutional way. The ignorance leaves generations of Iranian activists to struggle with the regime’s claims of legality and legitimacy. People are left to wonder whether or not, and to what extent, the 1979 revolution was a mistake. How can the current tyranny be fixed? Questioning the legitimacy of a popular revolution is hard. Even today, as protesters march in the streets of Tehran, some chant: “We did a revolution, we made a mistake!” Others chant about how Khamenei’s Velâyat-e Faqih within the confines of the theory is void (Khamenei is a murderer, his velayat is void). In the face of all of this, the state conveniently claims legality, legitimate use of force, and constitutionality based on the 1979 revolution.

All of this is a trap.

It is time for social movements in Iran and Iranian elites to take a page from Khomeini’s book. He didn’t focus on the constitutionality of the 1906 constitutional revolution nor the legitimacy of a constitutional monarchy. Instead, for 15 years, he focused on the legality and legitimacy of the reforms of 1925 and 1949. This enabled him to erode the regime’s claim of legality and legitimacy. Therefore, rather than staying within the confines of the 1979 narrative, Iranian elites should shift the popular rhetoric toward the unconstitutionality and illegitimacy of the 1989 silent counter-revolution. The focus should be on the promotion of a different theory of sovereignty, popular sovereignty, and the unconstitutionality of the current constitution. Khomeini himself famously said: “With the constitution being unconstitutional, people are not bound by any law passed by the parliament.” The defects of the 1979 revolution and its constitution are many. But at least it enjoyed a minimum level of revolutionary legality and legitimacy. The same cannot be said of the current constitution of Iran as revised unconstitutionally in 1989. In short, the question should not be whether the 1979 revolution was right or wrong. Rather, with all of its many faults and merits, the 1979 revolution is a stolen revolution. The current constitution is simply unconstitutional.