To Understand Russian Election Interference, Start with this Movie About Doping

In 2014, an amateur cyclist named Bryan Fogel had an eccentric idea for a film: He had just participated in a prestigious and grueling alpine stage race called the Haute Route in the Alps and had finished in 14th place. He decided to spend the next year not just training, but also doping. He meant to come back and run the race again the following year. He meant to not get caught for the doping. He expected the doping would vault him into the group of elite leaders who had finished above him.

In 2014, an amateur cyclist named Bryan Fogel had an eccentric idea for a film: He had just participated in a prestigious and grueling alpine stage race called the Haute Route in the Alps and had finished in 14th place. He decided to spend the next year not just training, but also doping. He meant to come back and run the race again the following year. He meant to not get caught for the doping. He expected the doping would vault him into the group of elite leaders who had finished above him. The performance difference, he believed, would prove that the group of cyclists who finished ahead of him were doping as well—and getting away with it. And he meant to reveal what he’d done.

It was a great premise for a documentary, but Fogel’s film did not go according to plan. For one thing, his doping effort failed to put him among the leaders. But the film, released last week on Netflix under the name Icarus, took a strange turn for another reason too: the only person Fogel could get to supervise his doping regime just happened to be supervising Russian President Vladimir Putin’s doping regime as well. And midway through the filming of Icarus, this scientist—Grigory Rodchenkov—thus found himself at the center of the Russian Olympic doping scandal. Rodchenkov defected, cooperated with investigators, and revealed the depths to which Putin’s government had gone to win Olympic medals. A documentary that was supposed to be about one man’s quixotic doping scheme came to be about a whole country’s menacing one.

Icarus is not about L’Affaire Russe or Russian intererence with the 2016 election. But if you want to understand L’Affaire Russe, you should watch it. Because Icarus is the story of the Russian government’s corruption of the integrity of supposedly neutral international processes and its use of covert action to tamper with those processes. If that sounds a little familiar, it should. It is easy to substitute in one’s mind as one watches this film a foreign country’s electoral system for the elaborate anti-doping testing regime whose systematic circumvention and undermining Icarus portrays. The corruption of process is similar. The motivation—the elevation of Russian national pride—significantly overlaps. The lies about it in the face of evidence are indistinguishable. And the result in both cases is a legitimacy crisis, of Olympic medals in one case and of a presidential election in another—a crisis which produces investigation and scandal.

Icarus is too good a film to make such a heavy-handed comparison explicitly. The film actually doesn’t offer any direct evidence that Fogel was even thinking about it. But if he wasn’t, the movie’s release in the middle of L’Affaire Russe is an extraordinarily well-timed thematic coincidence. Into the scandal and legitimacy crisis caused by Russian covert tampering in one complex system, Fogel drops an exquisitely well-told story of Russian tampering in another—and the scandal and fallout from it.

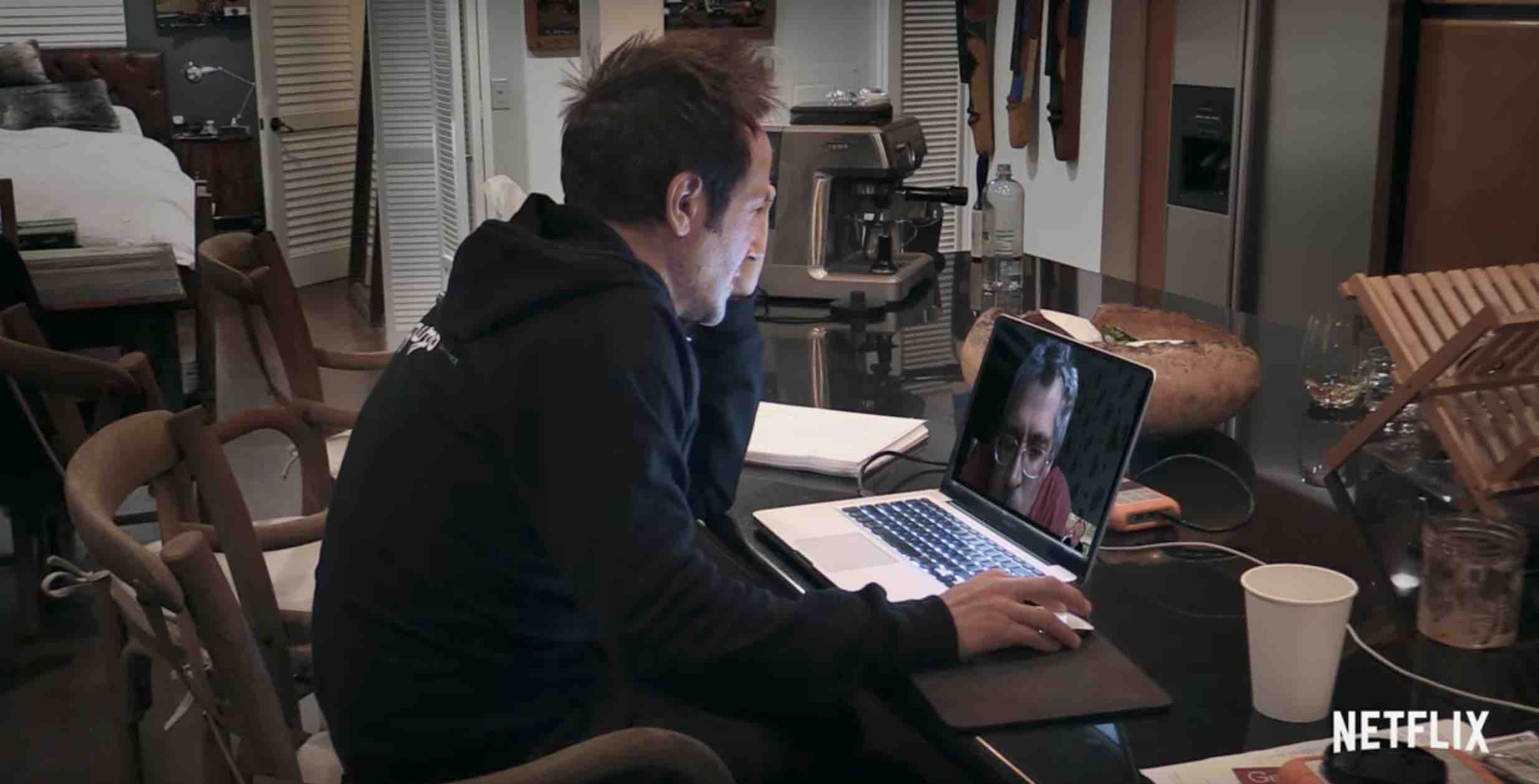

That Icarus is actually an international thriller about Russian corruption of anti-doping systems creeps up on the viewer slowly. The first part of the film portrays Fogel’s doping regimen, its integration with his training, and his burgeoning relationship with Rodchenkov, to whom he is introduced by a US anti-doping scientist who initially plans to supervise Fogel's doping but then gets cold feet and backs out.

It is never clear why this Russian scientist wants to participate in the scheme. He runs the Russian anti-doping lab. And he takes on the project even as that lab is under scrutiny from the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) for—as he later puts it—doing the perfect act of doublethink: running a doping and anti-doping program at the same time. But Rodchenkov is charming in his corruption. Whatever else he may be, he’s a great character. And the viewer, like Fogel, quickly becomes entranced with him and comes to worry about him as the WADA investigation heats up.

By the film’s midpoint, we realize that Icarus isn’t actually about a cyclist’s doping scheme at all. That’s just the entry point to the story of Rodchenkov, for us as it was for Fogel. Despite using banned performance enhancing drugs, Fogel finishes 27th in the Haute Route in 2015. So the premise of the original film turns out to be off. But shortly thereafter, the Russian doping scandal breaks in public and Rodchenkov is at the earthquake’s epicenter. He is dismissed as head of the lab. With Fogel’s help, he gets out of the country—leaving his wife and family behind—and Fogel installs him secretly in an apartment in Los Angeles shortly before his former boss dies under mysterious circumstances. And he begins talking—first to Fogel, then to law enforcement, then to the New York Times, and then to the WADA investigation. The movie follows him until his quite-moving entry into the Witness Protection Program, where he is still hidden because of ongoing threats to his life and safety.

Through it all, Fogel acts as his liason to the world. He represents him before the WADA investigation. He helps get him lawyers to represent him before U.S. authorities threatening to prosecute him. What began as a relationship in which Rodchenkov supervised Fogel’s doping becomes one in which Fogel supervises Rodchenkov’s defection and repentance and in which he documents the process—including the psychological process on Rodchenkov’s part of understanding the system he has helped run and the role he has played within it.

And what is that system? It is a system so committed to cheating in Olympic sports that Rodchenkov was lifted out of imprisonment in a psychiatric hospital because Putin wanted to ensure maximum doping at the Sochi games. It is a system in which the anti-doping lab worked with Russian intelligence to swap urine samples, open supposedly tamper-proof sample vials to do so, and use secret holes in walls to move samples around undetected by WADA cameras. It is a system which Rodchenkov confidently asserts tainted more than half of Russian medals at Sochi.

And it’s a system that Russia continues to deny—and deny with some degree of success. Because while the WADA investigation validated Rodchenkov’s allegations before the Rio Olympics, and while the Russian track and field team was banned from the games and WADA recommended Russia’s larger exclusion from the games in their entirety, the International Olympic Committee overturned this recommendation. An unrebutted finding of a state-sponsored doping program and active tampering by covert means with the international rules of play turned out not to be good enough to keep Russian athletes from competing at Rio.

In that sense, another key premise of Fogel’s movie turned out to be wrong—to wildly underestimate the corruption he was trying to expose: He thought if, with Rodchenkov’s assistance, he could expose relatively small-scale cheating in one sport, the system would have to respond. Instead, Rodchenkov exposed massive cheating organized by a large and powerful state, combined with what we might call “active measures” to prevent detection; he revealed that it was taking place across all sports. Yet the system ultimately shrugged and let Russian athletes come to Rio, where they won 56 medals. The IOC took the position that all of this evidence didn’t amount to specific evidence against individual athletes. And it thus helped Putin deny the premise—just as President Trump has shrugged and helped Putin deny a different premise and met with him warmly at the G20.

Which brings us to L’Affaire Russe. The analogy is not perfect and I don’t want to overstate it. But elements are genuinely similar, and you will watch Icarus with an unsettling feeling that the willingness to reach into other countries to distort the rules and disrupt systems of fair play, to deny doing so in the face of known and public reality, and to get away with it because international interlocutors want normalcy in the relationship with a large and powerful state is part of the essence of the Putin regime.

And you might come away as well with the sense that the biggest difference between the election tampering operations and the tampering with anti-doping systems is simply that no insider to the election operations—no Grigory Rodchenkov—happened to be making a movie with an American cyclist and decided to use the opportunity to tell the truth.

.jpg?sfvrsn=3611d515_4)