United States v. Menendez: When Bars of Gold May Not Be Enough

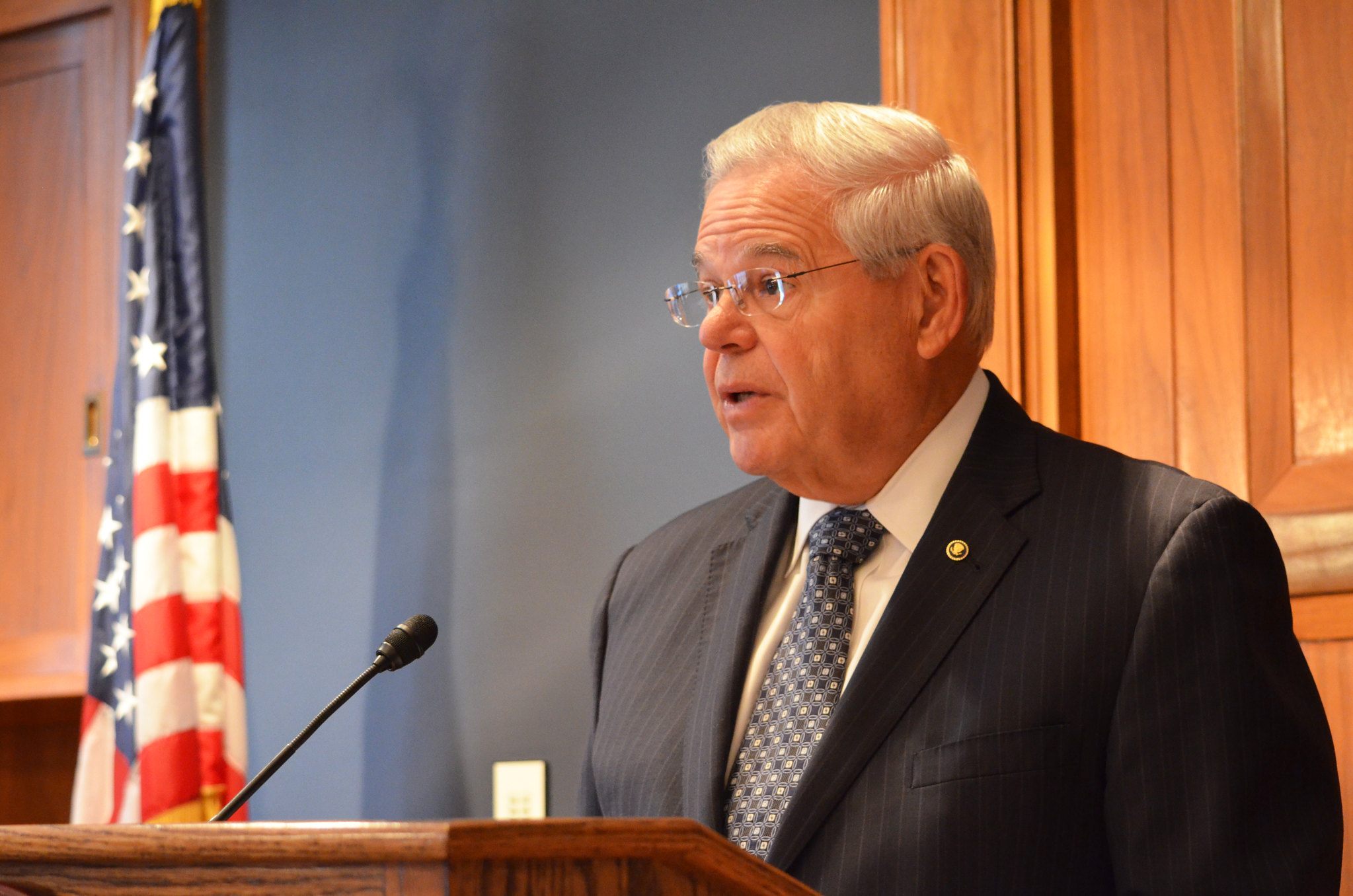

How McDonnell v. United States will shape the ongoing prosecution of New Jersey Sen. Robert Menendez.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

To what I now realize is wholly to their discredit, federal criminal indictments usually lack pictures. And when they do have pictures, the images are pretty boring. But the bars of gold depicted in the indictment of Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.)—evidence of what the government alleges was a bribery conspiracy—were magnificent. Way better than the pictures of former President Trump’s Mar-a-Lago bathroom. (I do hope this trend continues.)

Yet, oddly enough, public corruption prosecutions cannot rest solely on lurid details like the gold bars found in Menendez’s home, or the $90,000 seized from Rep. William J. Jefferson’s freezer back in 2005. Indeed, the Supreme Court has, in recent years, made a concerted effort to constrain federal corruption statutes. As I’ve written elsewhere, the Court’s core project appears to be the protection of what it considers “politics as usual” from the threat of prosecution. The Court’s concern is less that officials at all levels will suddenly wake up criminals, and more that prosecutors might use troubling, even partisan, criteria to select a few officials to go after for widely accepted conduct. To be sure, gold bars and cash stashed in freezers are not, so far as I know, features of normal politics. Still, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York will need to navigate the significant limitations that the Court has placed on the federal bribery statutes being used against Menendez and his co-defendants if it is to secure convictions in his case. It looks like the office is preparing to do just that.

Official Acts Under McDonnell

The key case shaping the Menendez prosecution—at least on the legal side—is McDonnell v. United States (2016). There, while acknowledging the “tawdry” facts of the case (in which Governor Robert F. McDonnell of Virginia and his wife was shown to have received a steady stream of expensive gifts from a businessman seeking state support for his nutritional product), the Court invalidated a conviction that might have rested on those gifts having been given in exchange for the governor’s commitment to “merely” make phone calls or set up meetings with state officials. As Chief Justice John Roberts explained for a unanimous Court, “conscientious public officials arrange meetings for constituents, contact other officials on their behalf, and include them in events all the time.”

The Court had, for some time, required that a “bribe” for the purposes of the federal bribery statute, 18 U.S.C. § 201, the “honest services” theory of mail fraud, 18 U.S.C. § 1346, and the Hobbs Act “under color of official right” theory of extortion involve a quid pro quo. Back in 1992, in Evans v. United States, it held that “the Government need only show that a public official has obtained a payment to which he was not entitled, knowing that the payment was made in return for official acts.” But the Court had never been clear as to what counted as an “official act.” Now, in McDonnell, it followed the lead of the lower court and looked to 18 U.S.C. § 201—even though that statute, which deals with only federal officials, was not and could not have been charged. And it restricted the definition of an “official act” to “a decision or action on a ‘question, matter, cause, suit, proceeding or controversy.’” Such decisions or actions “must involve a formal exercise of governmental power that is similar in nature to a lawsuit before a court, a determination before an agency, or a hearing before a committee.”

To what extent will the government be able to show that Menendez received payments in exchange for “official acts” within the meaning of McDonnell? I suspect that its charging theory will sharpen up by the time the jury is instructed, but the superseding indictment identifies a number of actions that Menendez agreed to take as part of his corrupt arrangement to benefit his co-defendants and the Arab Republic of Egypt. Menendez, the indictment charges, provided sensitive government information to Egypt; promised to use his power and authority to facilitate arms sales to Egypt; used his influence to disrupt a criminal investigation by the New Jersey attorney general of another defendant; recommended that the president nominate someone whom Menendez thought he could persuade to drop an investigation into a longtime fundraiser; and put pressure on Biden administration officials to revive stalled negotiations on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, among other things.

Whether these actions satisfy McDonnell’s definition of an “official act” remains to be seen. And the possibility that they might not highlights the inadequacy of the Supreme Court’s analysis. Perhaps for lower-ranking officials the only “official acts” that should count when corruptly sold are relatively formal ones. Perhaps the police officer who takes a bribe to run a license plate ought not be guilty of felony bribery under the McDonnell analysis (though he might well be guilty under the more expansive Federal Program Bribery statute, 18 U.S.C. § 666). But those operating at the highest levels of government—like a chair or ranking member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee—can reorient national policy with phone calls and letters, and ought not, at least in my humble opinion, be able to sell that influence with impunity.

Yet the McDonnell Court was likely well aware that its analysis was unduly restrictive. And it took pains to explain that the requisite “official act” might be that of an official other than the charged defendant. The “official act” requirement can be satisfied, it explained, when the defendant uses “his official position to exert pressure on another official to perform an ‘official act,’ or to advise another official, knowing or intending that such advice will form the basis for an ‘official act’” by that other official.

We can’t be sure what level of “pressure” on another official counts under this analysis. Should minimal intervention count as “pressure,” like merely setting a meeting or making a call—the very conduct that the Court held could not satisfy its bribery standard—could too easily support liability. Something more than simple outreach is doubtless required, but precisely what remains unclear. The Court may simply have moved the vagueness problem that so concerned it from one part of the statutory analysis to another.

The Menendez superseding indictment explicitly includes conduct that might well qualify under this “pressure” analysis. Menendez is alleged to have “improperly advised and pressured an official at the United States Department of Agriculture for the purpose of protecting” the monopoly on the export of halal meat exports to Egypt that, according to the indictment, was the means by which the government of Egypt rewarded Menendez and his co-conspirators for their efforts on his behalf. The indictment is less than clear about what the “official act” Menendez pressured the USDA official to make, but since the alleged goal was “that the USDA stop opposing” having but one halal certification, I imagine the “act” will be the official position the USDA would take on that matter. The indictment notes that, though the official “did not accede” to Menendez’s demand, the company kept its monopoly. But actual follow-through by a targeted official has never been a requirement for federal bribery charges.

The superseding indictment alleges other instances of “pressure” as well: Menendez is alleged to have put pressure on a New Jersey prosecutor to favorably resolve the prosecution of a co-defendant’s business associate. This is how the senator’s wife ended up with a $60,000 Mercedes-Benz convertible.

It’s worth noting that when Sen. Menendez was last indicted, in 2015, the indictment similarly alleged, among other things, corrupt efforts to pressure officials (in that case, in the State Department). After the jury deadlocked, however, the Justice Department opted to not re-prosecute those parts of the case that the trial judge, relying on McDonnell’s “advice” analysis and the “stream of benefits” analysis discussed below, had refused to dismiss.

One thing to watch as the case unfolds will be how and when the government resolves all the corrupt interactions alleged in the indictment. Which will it pitch as official acts by Menendez; which as official acts by others whom Mendendez put pressure on; and which as conspiratorial activity that, in and of itself, does not constitute an official act within the meaning of McDonnell? I don’t imagine complete resolution will be required in response to a motion to dismiss, but that remains to be seen. Certainly the government will want to clarify its theories by the time it sums up.

Ex Ante Clarity of the Alleged Quid Pro Quo

Another issue will remain, even assuming the government is deemed to have satisfied McDonnell’s “official act” requirement—an issue going to the ex ante clarity and specificity of the quid pro quo that the government will have to prove. In McDonnell, Chief Justice Roberts noted that the issue before a jury is “whether the public official agreed to perform an ‘official act’ at the time of the alleged quid pro quo.” The indictment charges just this sort of conduct: For instance, it connects the Mercedes-Benz convertible gift to Menendez’s agreement to pressure the New Jersey prosecutor. To what extent does McDonnell’s language preclude a charging theory that rests not on up-front clarity of this sort but on a more open-ended commitment to perform official acts?

Before McDonnell, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, in a 2007 opinion by then-Judge Sonia Sotomayor, held the quid pro quo satisfied, even in the absence of ex ante clarity, when an official agreed to act for the benefit of the bribing party “as the opportunities arose.” Since then, prodded by defendants—notably, New York state heavyweights Sheldon Silver and Dean Skelos—who argued that this standard is inconsistent with McDonnell, the circuit court has reconfigured its theory. Now it holds that, though a precise “official act” need not be contemplated at the time a bribe is accepted, the government needs to show that the official committed to take official action “on a specific and focused question or matter as the opportunities to take such action arose.” Indeed, the court found error (albeit harmless) in the failure to give this instruction in the prosecution of Joseph Percoco, whose convictions the Supreme Court reversed last term on other grounds.

It’s not clear whether the Supreme Court would agree with the Second Circuit’s “as opportunities arise” analysis. But the circuit analysis will control in this case unless and until it hears otherwise. Will the government be able to show the necessary ex ante clarity about “a specific and focused question or matter”? Because the indictment charges a single conspiracy that involved a complex set of official interventions by and benefits to Menendez and his wife, I expect the government will have to sharpen up its claims about particular bribe payments and particular questions or matters. The senator’s efforts to help the government of Egypt, particularly with respect to arms sales, will certainly play an important role in the trial—a role guaranteed by the recent addition of Foreign Agent Registration Act charges in the superseding indictment. But whether these efforts—and other efforts Menendez made to achieve other goals charged in the superseding indictment—will satisfy the circuit court’s revised “as opportunities arose” analysis also remains to be seen.

***

My focus here has been on the legal issues that Menendez and his co-defendants are likely to raise, and particularly on those grounded in McDonnell. These are not necessarily ones that the defendants will stress to the jury, should they go to trial. Indeed, the limits that the Court has put on what counts as a quid pro quo fly in the face of what a great many ordinary citizens would consider criminal bribery. As Judge Raymond Lohier Jr. has noted, it remains a (regrettably) open question whether the Second Circuit’s revised “as opportunities arise” analysis encompasses an official’s blanket promise, in exchange for a bribe, to “filter every official act through the lens of the payor’s interests.”

Should the proof at trial follow the narrative of the superseding indictment, jurors will hear a damning story of how a halal export monopoly was created in order to funnel money to a powerful senator to ensure that pesky allegations of human rights violations would not prevent Egypt from getting military aid. Jurors will have to be instructed properly, and, should the defendants be convicted, an appellate court will likely scrutinize the factual basis for a guilty verdict with care. But I don’t imagine defense counsel will count on jurors to do the fine line-drawing that the Supreme Court has required. At the heart of the defense may well be the simple factual claim that there is no evidence of any quid pro quo of any sort: The senator fought for what he believed was in the public interest, and he just happened to have generous friends. The gold bars, just a quirky gift.