Unmasking: A Primer on the Issues, Rules, and Possible Reforms

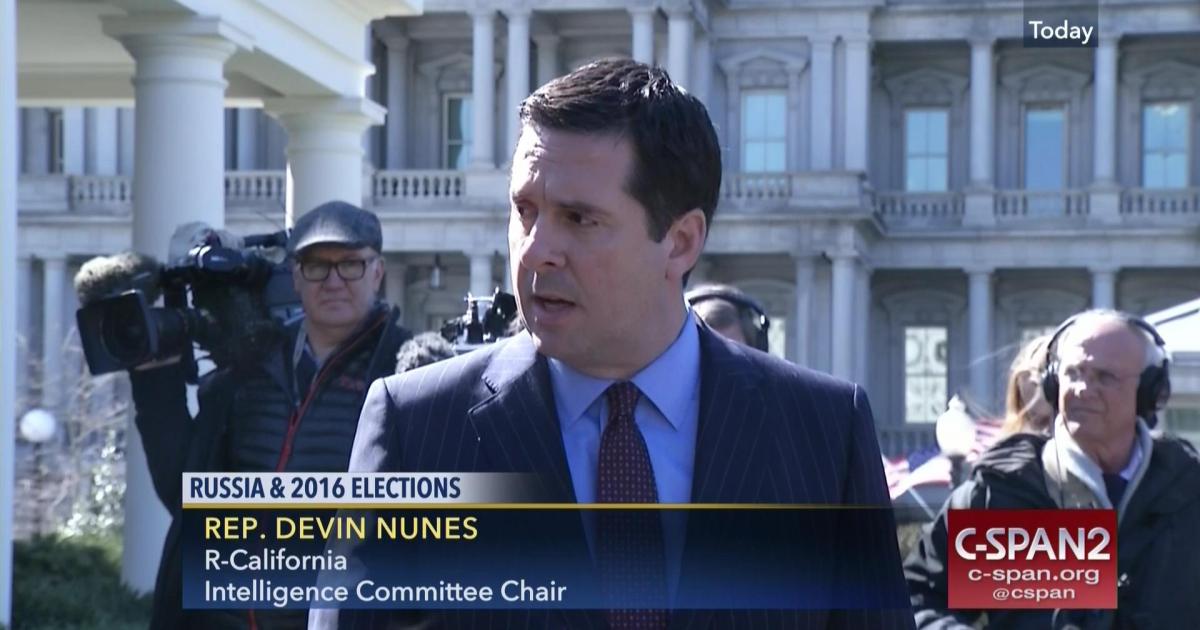

Earlier today, HPSCI Chair Devin Nunes announced he will “temporarily” recuse himself from his committee’s Trump/Russia/Surveillance investigation (in his stead, Representative Conaway will take the helm, with support from Representatives Gowdy and Rooney).

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Earlier today, HPSCI Chair Devin Nunes announced he will “temporarily” recuse himself from his committee’s Trump/Russia/Surveillance investigation (in his stead, Representative Conaway will take the helm, with support from Representatives Gowdy and Rooney). It does not follow, however, that HPSCI now will focus primarily on just the campaign-influence aspects of this story. Rep. Gowdy in particular seems to be especially concerned with the possibility that intelligence has been or is being used for political purposes, and the HPSCI investigation surely will continue to focus in no small part on that set of questions.

All of which made me think that it might be useful to produce a FAQ-style overview of the easily-confused issues associated with the surveillance side of this controversy. So, here goes:

Q: Does any part of this controversy concern the original decision to conduct surveillance?

For the most observers so far, the answer is no.

As most readers will be aware, the larger story apparently begins with surveillance of communications (probably phone conversations, though perhaps emails or texts instead or in addition) of one or more uncontroversial targets—that is, persons who were conventional objects of foreign-intelligence interest, not persons who were associated with the Trump campaign. The Trump campaign enters into the picture only because of the happenstance that collection on those proper foreign-intelligence target(s) turned out to capture conversations with (or about) one or more Trump campaign associates. On this account (which finds support in the otherwise-inflammatory public statements from HPSCI Chair Devin Nunes), a government agency was acting properly in the first instance under one of three possible surveillance paradigms (perhaps it was an ordinary FISA Title 1 order; perhaps it was collection made possible under “Section 702”; perhaps it was overseas collection under 12,333). Issues arise, on this view, only a result of what happened next.

Before turning to what happened next, though, let’s acknowledge a competing perspective. Some have suggested that the original collection decision was not so innocent after all, and that the whole thing was a sham designed to obscure the government’s true purpose: to surveil Trump campaign officials while pretending to be interested in the ostensible foreign-intelligence target. That sort of thing is called “reverse targeting,” and for obvious reasons it’s not permitted. If it occurred here, it would indeed be a huge story. So far as I have seen, however, there is no evidence whatsoever to support the claim that this occurred. Which does not surprise me; pulling off an abuse of this kind would require a conspiracy involving no small number of career professionals, against the backdrop of internal control systems and institutional culture that for decades have treated such behavior as an abuse that must be avoided.

Q: So is the problem, instead, that there was “incidental” collection?

At this point I’m proceeding on the theory, described above, that the original surveillance was a perfectly lawful and ordinary—indeed, desirable—collection intended to yield foreign intelligence. This account does accept, however, that US persons who were not the targets of this collection were caught up in it when they communicated with the target. Is that fact, without more, a problem?

No. The label for this situation is “incidental collection.” Some amount of incidental collection is inevitable, for targets routinely communicate with non-targets and, sometimes, that other party to the call, email, or text will turn out to be a US person. It’s silly to talk about this as if it is inherently wrong. What matters is how the government handles the communication once it becomes clear that incidental collection has occurred. Are there rules that stop officials from blurting out the information to the public? And are there rules that limit their ability to spread the information internally, to other government officials?

These are related questions, for the easier it is to spread information about a US person to others within the government, the greater the chance that the information could in turn end up being leaked to the public at large. That, in fact, appears to be a key element in the complaints being lodged by President Trump and his supporters. So, let’s start with the rules limiting intra-government information sharing.

Q: What are the rules limiting who within the government gets to see the identity of a US person caught up in incidental collection?

We find the relevant rules in United States Signals Intelligence Directive 18, which governs NSA’s operations.

Section 7 of this rulebook, titled “Dissemination,” addresses this issue in two ways. First, it sets forth a substantive test for when an intelligence product derived from signals intelligence (a “SIGINT report”) can include the name of a U.S. person. Second, it creates rules regarding who within NSA has authority to determine that the test has been satisfied. We’ll take those in order.

Q: What is the substantive test for circulating the US person’s name?

The U.S. person’s name can be included in the SIGINT report only in three circumstances. Two of those (when the person has affirmatively consented, and when the information is public anyway) do not appear to be relevant here. So what matters is the third scenario, in which the U.S. person’s identity “is necessary to understand the foreign intelligence information or assess its importance.”

The same section goes on to list seven “non-exclusive” examples of situations that would clear this bar. Here’s a short, paraphrased version of that list:

(1) The communication suggests the US person has become an agent of a foreign power

(2) The communication shows the US person is involved in leaking classified information

(3) The communication links the US person to international drug trafficking

(4) The communication shows the US person may be involved in other crime (and dissemination in that case is strictly limited to a law enforcement agency)

(5) The communication shows that a foreign intelligence service is targeting the US person in some fashion

(6) The identity of the US person somehow sheds light on a “possible threat to the safety of any person or organization”

(7) The US person at issue currently is a “senior official of the Executive Branch of the U.S. Government,” though in that case the person’s title rather than their name should be used.

Do any of the listed examples above seem applicable to the current controversy? We’d have to know more, of course, but it is easy to imagine conversations that would fit example (5) (i.e., examples in which it seems a Trump campaign official has been targeted by a foreign intelligence service). It also is possible that example (4) applied, if the particular US person might have been in violation of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (see Steve Vladeck’s detailed post here). But at any rate, it is not necessary to show that one of the seven explicit examples applies; the list is illustrative, not exhaustive. It just isn’t that hard to see how, when there is communications between a foreign-intelligence target and a person associated with a presidential campaign, the assessment of the situation requires knowing who in particular that US person is.

Q: What are the procedural safeguards to ensure this test is applied in good faith?

Section 7 adds a procedural safeguard in the form of limits on which officials get to make this decision.

At the most extreme, that authority could be limited to the Director of NSA. And that’s the rule, under Section7, when the situation involves (i) a member or employee of Congress (not applicable here), or (ii) dissemination of the SIGINT report to a law enforcement agency of non-narcotics information. That first situation probably did not apply here, but it’s possible the second one did. If there was a law enforcement angle, therefore, the decision to use the real name of the Trump campaign officials involved would have been made by Admiral Mike Rogers (and also would have required review by NSA’s general counsel, under a separate section of these rules).

So what about all those other scenarios? The leash is still held tight, but below the level of the Director himself. Section 7 names various senior NSA managers who may make the decision in such cases. Admiral Rogers recently testified that this group encompasses about 20 people in total.

Q: But if that is the process, then where do “unmasking” and Susan Rice fit in?

In actual practice, NSA is more cautious than those rules strictly require. This creates situations in which analysts or ultimate customers (like, say, the National Security Advisor) might have to affirmatively request disclosure of the US person identities. Here’s why:

Under the rules just described, NSA might use the real names of US persons in SIGINT reports in the first instance. But that’s not what happens normally. NSA is far more cautious about this issue (and, if I’m not mistaken, they are affirmatively obliged to take this posture when the SIGINT report draws on the fruits of a Title 1 FISA order or Section 702 collection). SIGINT reports in the first instance thus typically use a mask along the lines of “[United States Person A].” If and when a proper recipient of the report decides that he or she needs the actual identity to make proper sense of the communication, that person then reaches back to the originating unit to request unmasking pursuant to the rules I just described.

Apparently, that is precisely what happened here. Susan Rice—the National Security Advisor at the time—properly received SIGINT reports. In them, the names of US persons were masked. She requested unmasking under the rules described above. The requests were approved, and the names were then provided.

Could this have been a politicized abuse, in which unmasking occurred despite failure to meet the standard? There are many who distrust Susan Rice, and find that prospect plausible. But note that she cannot have done this on her own. The decision lies with the agency, as noted above. You have to believe that at least one of the twenty decisionmakers (perhaps even the Director) was somehow cajoled into cooperation.

Q: Ok, so maybe a conspiracy to act in bad faith is far-fetched. Is that the end of the discussion?

No, for two reasons. First, this information didn’t stay within the government; it leaked to the public. Second, even if the decision to use the real names was proper under the rules, it raises the question whether those rules are calibrated as well as they could be.

1. The leak issue:

This is a very serious issue. One need not buy into any of the complaints reviewed above (reverse targeting, bad-faith unmasking, etc.) in order to be concerned about the decision by someone with access to the fruits of SIGINT collection to share that information with the media and thus the public. The person(s) involved no doubt felt justified by larger concerns about the national interest, yet the same can be (and often is) said by leakers with quite different motivations, such as Edward Snowden. This cuts both ways, of course; some will be moved to investigate this leak more thoroughly in light of the comparison, others quite the opposite perhaps.

2. Do we need to tighten the standard for using real US person names?

That’s the question journalist Eli Lake raised in this very-interesting piece on Bloomberg View yesterday. So far, I’m not convinced that the current system needs this sort of change, but it’s clearly a question worthy of reflection. Here are some initial thoughts:

1. The rules described above constrain both substantively and procedurally. If one is worried the current structure is too loose, then one might choose to tighten along either of those dimensions.

2. Eli suggests the possibility of a substantive tightening, perhaps by limiting the use of real US names to situations involving not just foreign intelligence of any kind but, instead, only where certain high-profile areas (counterterrorism, etc.) are implicated, and perhaps with a requirement of imminent-harm woven in as well. I’m not yet persuaded this is a good idea, for I am not sure we want to foreswear this particular kind of intelligence insight in some areas that concededly matter for foreign intelligence yet might not make this list of most-exigent scenarios. If changes is needed, I’d rather see consideration of procedural tweaks.

3. What might those tweaks look like? I don’t think it would make sense to try to have the NSA Director make the call personally in all instances, though perhaps that could help without unduly burdening the Director. It might make more sense to require some additional mechanisms in the nature of oversight and accountability. For example, one can imagine a rule affirmatively requiring general counsel sign-off in every such instance, along with annual post-hoc review of all such decisions by the Inspector General and a closed-door briefing to SSCI and HPSCI of the results of that review. And if only PCLOB had a quorum, that body might be charged with conducting an investigation as well.

[Note: I’m quite aware there may well be layers of rules and practice that already require just these sort of things, or something else relevant, and I’m just missing it thanks to my outsider perspective or lack of due diligence. I’ll be happy to post an update if someone has something that deserves additional mention.]

And that will have to be enough, for now. No doubt the story will continue to evolve.